Recently Published Bulletin Reports

Kadovar (Papua New Guinea) An ash plume and weak thermal anomaly during May 2023

San Miguel (El Salvador) Small gas-and-ash explosions during March and May 2023

Ebeko (Russia) Continued explosions, ash plumes, and ashfall during October 2022-May 2023

Home Reef (Tonga) Discolored plumes continued during November 2022-April 2023

Semisopochnoi (United States) Occasional explosions, ash deposits, and gas-and-steam plumes during December 2022-May 2023

Ambae (Vanuatu) New lava flow, ash plumes, and sulfur dioxide plumes during February-May 2023

Ibu (Indonesia) Daily ash explosions continue, along with thermal anomalies in the crater, October 2022-May 2023

Dukono (Indonesia) Continuing ash emissions, SO2 plumes, and thermal signals during October 2022-May 2023

Sabancaya (Peru) Explosions, gas-and-ash plumes, and thermal activity persist during November 2022-April 2023

Sheveluch (Russia) Significant explosions destroyed part of the lava-dome complex during April 2023

Bezymianny (Russia) Explosions, ash plumes, lava flows, and avalanches during November 2022-April 2023

Chikurachki (Russia) New explosive eruption during late January-early February 2023

Kadovar (Papua New Guinea) — June 2023  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Kadovar

Papua New Guinea

3.608°S, 144.588°E; summit elev. 365 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

An ash plume and weak thermal anomaly during May 2023

Kadovar is a 2-km-wide island that is the emergent summit of a Bismarck Sea stratovolcano. It lies off the coast of New Guinea, about 25 km N of the mouth of the Sepik River. Prior to an eruption that began in 2018, a lava dome formed the high point of the volcano, filling an arcuate landslide scarp open to the S. Submarine debris-avalanche deposits occur to the S of the island. The current eruption began in January 2018 and has comprised lava effusion from vents at the summit and at the E coast; more recent activity has consisted of ash plumes, weak thermal activity, and gas-and-steam plumes (BGVN 48:02). This report covers activity during February through May 2023 using information from the Darwin Volcanic Ash Advisory Center (VAAC) and satellite data.

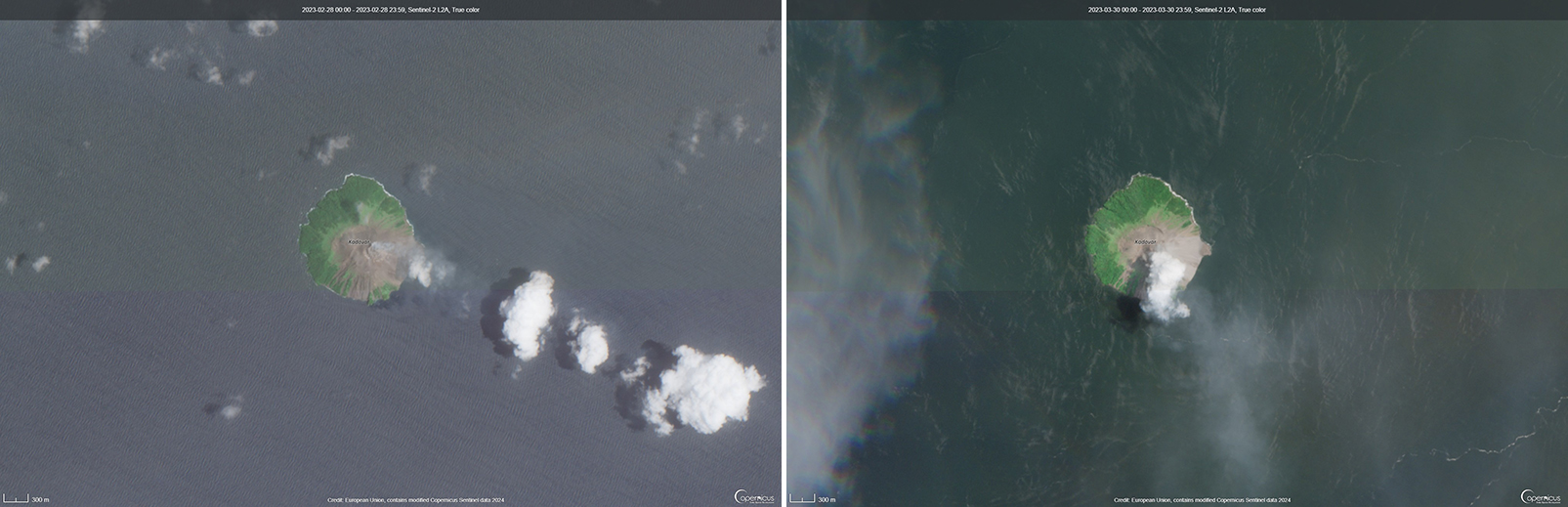

Activity during the reporting period was relatively low and mainly consisted of white gas-and-steam plumes that were visible in natural color satellite images on clear weather days (figure 67). According to a Darwin VAAC report, at 2040 on 6 May an ash plume rose to 4.6 km altitude and drifted W; by 2300 the plume had dissipated. MODIS satellite instruments using the MODVOLC thermal algorithm detected a single thermal hotspot on the SE side of the island on 7 May. Weak thermal activity was also detected in a satellite image on the E side of the island on 14 May, accompanied by a white gas-and-steam plume that drifted SE (figure 68).

Geologic Background. The 2-km-wide island of Kadovar is the emergent summit of a Bismarck Sea stratovolcano of Holocene age. It is part of the Schouten Islands, and lies off the coast of New Guinea, about 25 km N of the mouth of the Sepik River. Prior to an eruption that began in 2018, a lava dome formed the high point of the andesitic volcano, filling an arcuate landslide scarp open to the south; submarine debris-avalanche deposits occur in that direction. Thick lava flows with columnar jointing forms low cliffs along the coast. The youthful island lacks fringing or offshore reefs. A period of heightened thermal phenomena took place in 1976. An eruption began in January 2018 that included lava effusion from vents at the summit and at the E coast.

Information Contacts: Darwin Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre (VAAC), Bureau of Meteorology, Northern Territory Regional Office, PO Box 40050, Casuarina, NT 0811, Australia (URL: http://www.bom.gov.au/info/vaac/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

San Miguel (El Salvador) — June 2023  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

San Miguel

El Salvador

13.434°N, 88.269°W; summit elev. 2130 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Small gas-and-ash explosions during March and May 2023

San Miguel in El Salvador is a broad, deep crater complex that has been frequently modified by eruptions recorded since the early 16th century and consists of the summit known locally as Chaparrastique. Flank eruptions have produced lava flows that extended to the N, NE, and SE during the 17-19th centuries. The most recent activity has consisted of minor ash eruptions from the summit crater. The current eruption period began in November 2022 and has been characterized by frequent phreatic explosions, gas-and-ash emissions, and sulfur dioxide plumes (BGVN 47:12). This report describes small gas-and-ash explosions during December 2022 through May 2023 based on special reports from the Ministero de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (MARN).

Activity has been relatively low since the last recorded explosions on 29 November 2022. Seismicity recorded by the San Miguel Volcano Station (VSM) located on the N flank at 1.7 km elevation had decreased by 7 December. Sulfur dioxide gas measurements taken with DOAS (Differential Optical Absorption Spectroscopy) mobile equipment were below typical previously recorded values: 300 tons per day (t/d). During December, small explosions were recorded by the seismic network and manifested as gas-and-steam emissions.

Gas-and-ash explosions in the crater occurred during January 2023, which were recorded by the seismic network. Sulfur dioxide values remained low, between 300-400 t/d through 10 March. At 0817 on 14 January a gas-and-ash emission was visible in webcam images, rising just above the crater rim. Some mornings during February, small gas-and-steam plumes were visible in the crater. On 7 March at 2252 MARN noted an increase in degassing from the central crater; gas emissions were constantly observed through the early morning hours on 8 March. During the early morning of 8 March through the afternoon on 9 March, 12 emissions were registered, some accompanied by ash. The last gas-and-ash emission was recorded at 1210 on 9 March; very fine ashfall was reported in El Tránsito (10 km S), La Morita (6 km W), and La Piedrita (3 km W). The smell of sulfur was reported in Piedra Azul (5 km SW). On 16 March MARN reported that gas-and-steam emissions decreased.

Low degassing and very low seismicity were reported during April; no explosions have been detected between 9 March and 27 May. The sulfur dioxide emissions remained between 350-400 t/d; during 13-20 April sulfur dioxide values fluctuated between 30-300 t/d. Activity remained low through most of May; on 23 May seismicity increased. An explosion was detected at 1647 on 27 May generated a gas-and-ash plume that rose 700 m high (figure 32); a decrease in seismicity and gas emissions followed. The DOAS station installed on the W flank recorded sulfur dioxide values that reached 400 t/d on 27 May; subsequent measurements showed a decrease to 268 t/d on 28 May and 100 t/d on 29 May.

Geologic Background. The symmetrical cone of San Miguel, one of the most active volcanoes in El Salvador, rises from near sea level to form one of the country's most prominent landmarks. A broad, deep, crater complex that has been frequently modified by eruptions recorded since the early 16th century caps the truncated unvegetated summit, also known locally as Chaparrastique. Flanks eruptions of the basaltic-andesitic volcano have produced many lava flows, including several during the 17th-19th centuries that extended to the N, NE, and SE. The SE-flank flows are the largest and form broad, sparsely vegetated lava fields crossed by highways and a railroad skirting the base of the volcano. Flank vent locations have migrated higher on the edifice during historical time, and the most recent activity has consisted of minor ash eruptions from the summit crater.

Information Contacts: Ministero de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (MARN), Km. 5½ Carretera a Nueva San Salvador, Avenida las Mercedes, San Salvador, El Salvador (URL: http://www.snet.gob.sv/ver/vulcanologia).

Ebeko

Russia

50.686°N, 156.014°E; summit elev. 1103 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Continued explosions, ash plumes, and ashfall during October 2022-May 2023

Ebeko, located on the N end of Paramushir Island in the Kuril Islands, consists of three summit craters along a SSW-NNE line at the northern end of a complex of five volcanic cones. Eruptions date back to the late 18th century and have been characterized as small-to-moderate explosions from the summit crater, accompanied by intense fumarolic activity. The current eruption period began in June 2022 and has recently consisted of frequent explosions, ash plumes, and thermal activity (BGVN 47:10). This report covers similar activity during October 2022 through May 2023, based on information from the Kamchatka Volcanic Eruptions Response Team (KVERT) and satellite data.

Activity during October consisted of explosive activity, ash plumes, and occasional thermal anomalies. Visual data by volcanologists from Severo-Kurilsk showed explosions producing ash clouds up to 2.1-3 km altitude which drifted E, N, NE, and SE during 1-8, 10, 16, and 18 October. KVERT issued several Volcano Observatory Notices for Aviation (VONA) on 7, 13-15, and 27 October 2022, stating that explosions generated ash plumes that rose to 2.3-4 km altitude and drifted 5 km E, NE, and SE. Ashfall was reported in Severo-Kurilsk (Paramushir Island, about 7 km E) on 7 and 13 October. Satellite data showed a thermal anomaly over the volcano on 15-16 October. Visual data showed ash plumes rising to 2.5-3.6 km altitude on 22, 25-29, and 31 October and moving NE due to constant explosions.

Similar activity continued during November, with explosions, ash plumes, and ashfall occurring. KVERT issued VONAs on 1-2, 4, 6-7, 9, 13, and 16 November that reported explosions and resulting ash plumes that rose to 1.7-3.6 km altitude and drifted 3-5 km SE, ESE, E, and NE. On 1 November ash plumes extended as far as 110 km SE. On 5, 8, 12, and 24-25 November explosions and ash plumes rose to 2-3.1 km altitude and drifted N and E. Ashfall was observed in Severo-Kurilsk on 7 and 16 November. A thermal anomaly was visible during 1-4, 16, and 20 November. Explosions during 26 November rose as high as 2.7 km altitude and drifted NE (figure 45).

Explosions and ash plumes continued to occur in December. During 1-2 and 4 December volcanologists from Severo-Kurilsk observed explosions that sent ash to 1.9-2.5 km altitude and drifted NE and SE (figure 46). VONAs were issued on 5, 9, and 16 December reporting that explosions generated ash plumes rising to 1.9 km, 2.6 km, and 2.4 km altitude and drifted 5 km SE, E, and NE, respectively. A thermal anomaly was visible in satellite imagery on 16 December. On 18 and 27-28 December explosions produced ash plumes that rose to 2.5 km altitude and drifted NE and SE. On 31 December an ash plume rose to 2 km altitude and drifted NE.

Explosions continued during January 2023, based on visual observations by volcanologists from Severo-Kurilsk. During 1-7 January explosions generated ash plumes that rose to 4 km altitude and drifted NE, E, W, and SE. According to VONAs issued by KVERT on 2, 4, 10, and 23 January, explosions produced ash plumes that rose to 2-4 km altitude and drifted 5 km N, NE, E, and ENE; the ash plume that rose to 4 km altitude occurred on 10 January (figure 47). Satellite data showed a thermal anomaly during 3-4, 10, 13, 16, 21, 22, and 31 January. KVERT reported that an ash cloud on 4 January moved 12 km NE. On 6 and 9-11 January explosions sent ash plumes to 4.5 km altitude and drifted W and ESE. On 13 January an ash plume rose to 3 km altitude and drifted SE. During 20-24 January ash plumes from explosions rose to 3.7 km altitude and drifted SE, N, and NE. On 21 January the ash plume drifted as far as 40 km NE. During 28-29 and 31 January and 1 February ash plumes rose to 4 km altitude and drifted NE.

During February, explosions, ash plumes, and ashfall were reported. During 1, 4-5 and 7-8 February explosions generated ash plumes that rose to 4.5 km altitude and drifted E and NE; ashfall was observed on 5 and 8 February. On 6 February an explosion produced an ash plume that rose to 3 km altitude and drifted 7 km E, causing ashfall in Severo-Kurilsk. A thermal anomaly was visible in satellite data on 8, 9, 13, and 21 February. Explosions on 9 and 12-13 February produced ash plumes that rose to 4 km altitude and drifted E and NE; the ash cloud on 12 February extended as far as 45 km E. On 22 February explosions sent ash to 3 km altitude that drifted E. During 24 and 26-27 February ash plumes rose to 4 km altitude and drifted E. On 28 February an explosion sent ash to 2.5-3 km altitude and drifted 5 km E; ashfall was observed in Severo-Kurilsk.

Activity continued during March; visual observations showed that explosions generated ash plumes that rose to 3.6 km altitude on 3, 5-7, and 9-12 March and drifted E, NE, and NW. Thermal anomalies were visible on 10, 13, and 29-30 March in satellite imagery. On 18, 21-23, 26, and 29-30 March explosions produced ash plumes that rose to 2.8 km altitude and drifted NE and E; the ash plumes during 22-23 March extended up to 76 km E. A VONA issued on 21 March reported an explosion that produced an ash plume that rose to 2.8 km altitude and drifted 5 km E. Another VONA issued on 23 March reported that satellite data showed an ash plume rising to 3 km altitude and drifted 14 km E.

Explosions during April continued to generate ash plumes. On 1 and 4 April an ash plume rose to 2.8-3.5 km altitude and drifted SE and NE. A thermal anomaly was visible in satellite imagery during 1-6 April. Satellite data showed ash plumes and clouds rising to 2-3 km altitude and drifting up to 12 km SW and E on 3 and 6 April (figure 48). KVERT issued VONAs on 3, 5, 14, 16 April describing explosions that produced ash plumes rising to 3 km, 3.5 km, 3.5 km, and 3 km altitude and drifting 5 km S, 5 km NE and SE, 72 km NNE, and 5 km NE, respectively. According to satellite data, the resulting ash cloud from the explosion on 14 April was 25 x 7 km in size and drifted 72-104 km NNE during 14-15 April. According to visual data by volcanologists from Severo-Kurilsk explosions sent ash up to 3.5 km altitude that drifted NE and E during 15-16, 22, 25-26, and 29 April.

The explosive eruption continued during May. Explosions during 3-4, 6-7, and 9-10 May generated ash plumes that rose to 4 km altitude and drifted SW and E. Satellite data showed a thermal anomaly on 3, 9, 13-14, and 24 May. During 12-16, 23-25, and 27-28 May ash plumes rose to 3.5 km altitude and drifted in different directions due to explosions. Two VONA notices were issued on 16 and 25 May, describing explosions that generated ash plumes rising to 3 km and 3.5 km altitude, respectively and extending 5 km E. The ash cloud on 25 May drifted 75 km SE.

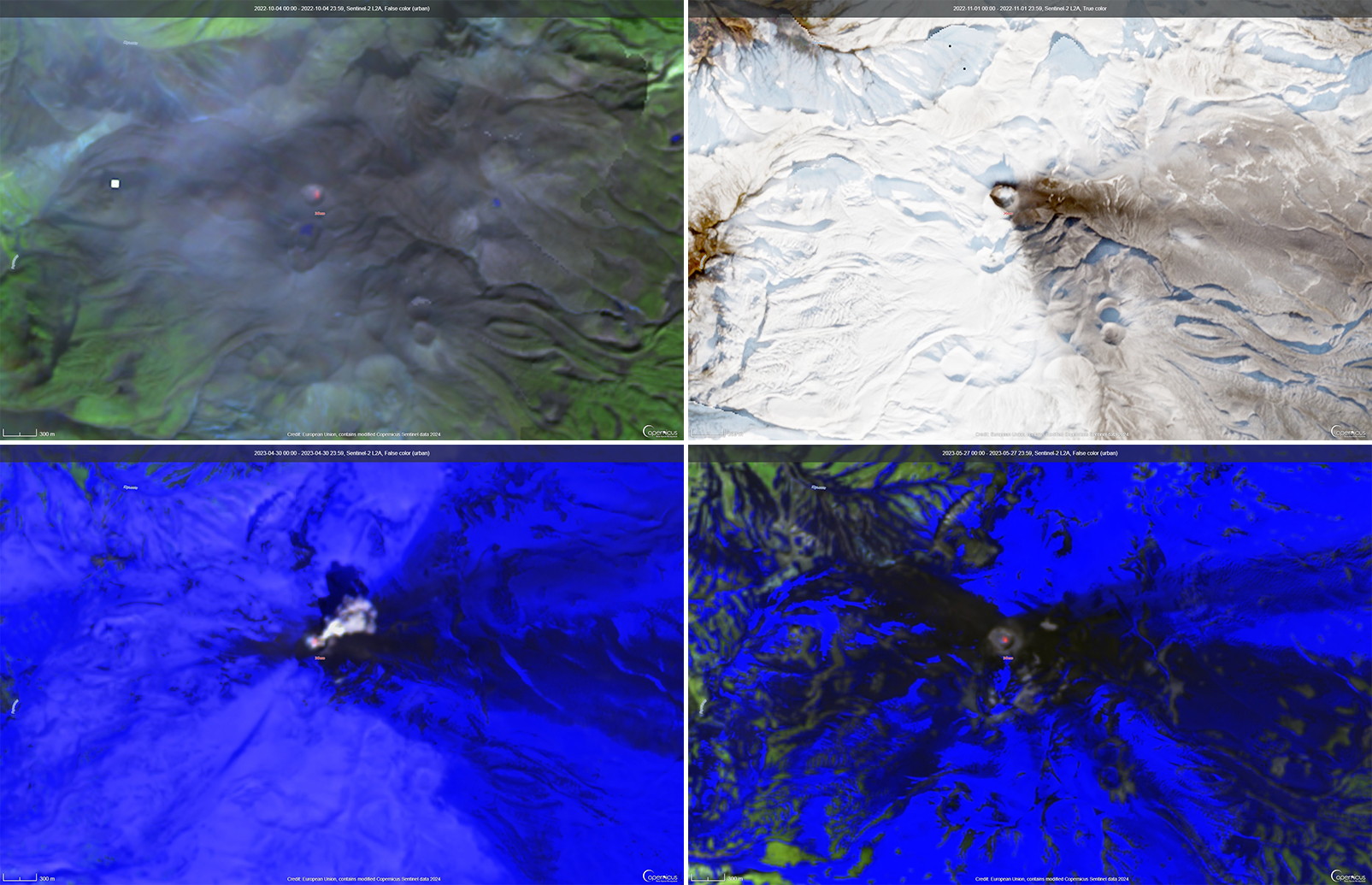

Thermal activity in the summit crater, occasionally accompanied by ash plumes and ash deposits on the SE and E flanks due to frequent explosions, were visible in infrared and true color satellite images (figure 49).

Geologic Background. The flat-topped summit of the central cone of Ebeko volcano, one of the most active in the Kuril Islands, occupies the northern end of Paramushir Island. Three summit craters located along a SSW-NNE line form Ebeko volcano proper, at the northern end of a complex of five volcanic cones. Blocky lava flows extend west from Ebeko and SE from the neighboring Nezametnyi cone. The eastern part of the southern crater contains strong solfataras and a large boiling spring. The central crater is filled by a lake about 20 m deep whose shores are lined with steaming solfataras; the northern crater lies across a narrow, low barrier from the central crater and contains a small, cold crescentic lake. Historical activity, recorded since the late-18th century, has been restricted to small-to-moderate explosive eruptions from the summit craters. Intense fumarolic activity occurs in the summit craters, on the outer flanks of the cone, and in lateral explosion craters.

Information Contacts: Kamchatka Volcanic Eruptions Response Team (KVERT), Far Eastern Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, 9 Piip Blvd., Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, 683006, Russia (URL: http://www.kscnet.ru/ivs/kvert/); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Home Reef

Tonga

18.992°S, 174.775°W; summit elev. -10 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Discolored plumes continued during November 2022-April 2023

Home Reef is a submarine volcano located in the central Tonga islands between Lateiki (Metis Shoal) and Late Island. The first recorded eruption occurred in the mid-19th century, when an ephemeral island formed. An eruption in 1984 produced a 12-km-high eruption plume, a large volume of floating pumice, and an ephemeral island 500 x 1,500 m wide, with cliffs 30-50 m high that enclosed a water-filled crater. Another island-forming eruption in 2006 produced widespread pumice rafts that drifted as far as Australia; by 2008 the island had eroded below sea level. The previous eruption occurred during October 2022 and was characterized by a new island-forming eruption, lava effusion, ash plumes, discolored water, and gas-and-steam plumes (BGVN 47:11). This report covers discolored water plumes during November 2022 through April 2023 using satellite data.

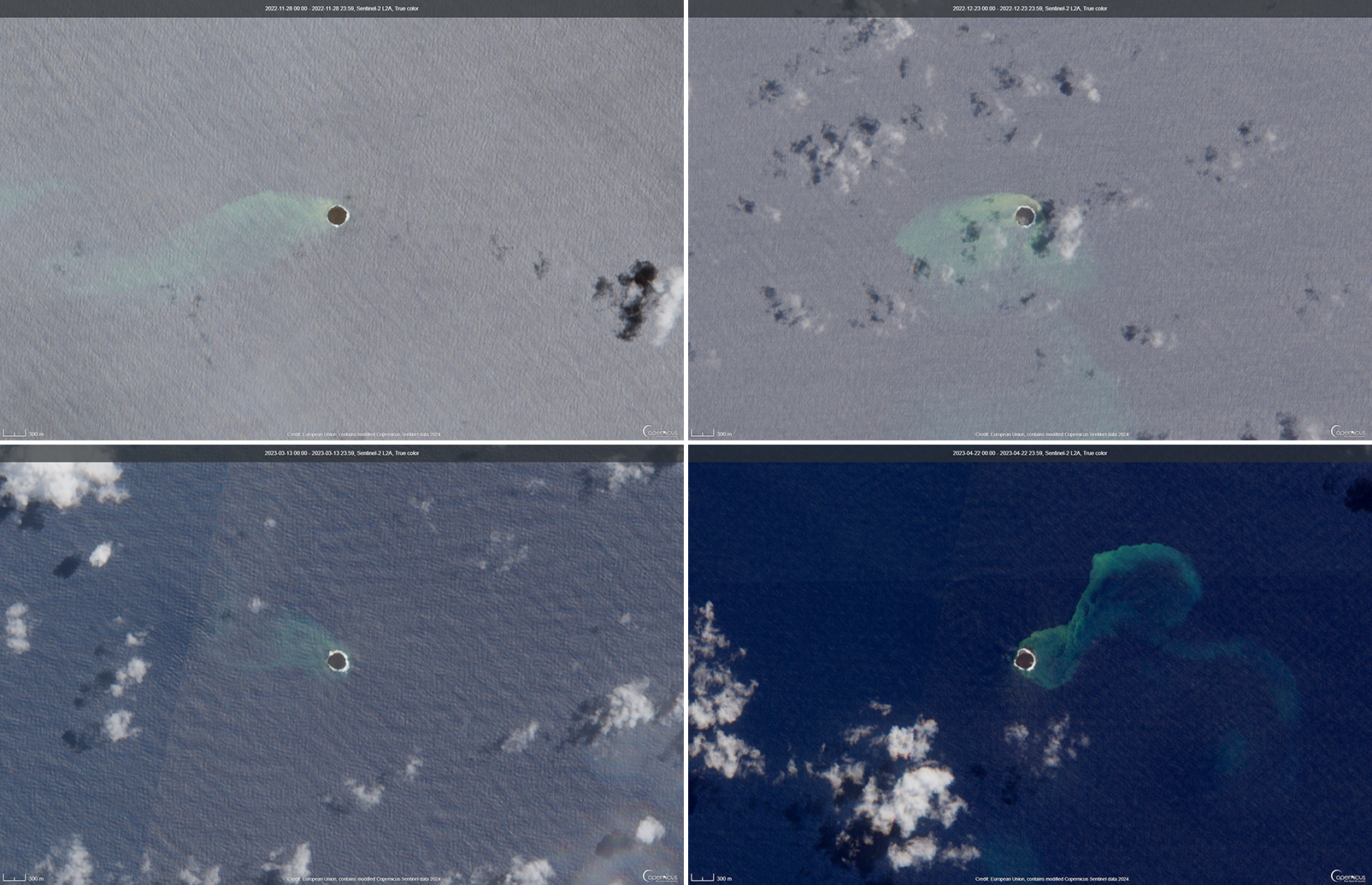

Discolored plumes continued during the reporting period and were observed in true color satellite images on clear weather days. Satellite images show light green-yellow discolored water extending W on 8 and 28 November 2022 (figure 31), and SW on 18 November. Light green-yellow plumes extended W on 3 December, S on 13 December, SW on 18 December, and W and S on 23 December (figure 31). On 12 January 2023 discolored green-yellow plumes extended to the NE, E, SE, and N. The plume moved SE on 17 January and NW on 22 January. Faint discolored water in February was visible moving NE on 1 February. A discolored plume extended NW on 8 and 28 March and NW on 13 March (figure 31). During April, clear weather showed green-blue discolored plumes moving S on 2 April, W on 7 April, and NE and S on 12 April. A strong green-yellow discolored plume extended E and NE on 22 April for several kilometers (figure 31).

Geologic Background. Home Reef, a submarine volcano midway between Metis Shoal and Late Island in the central Tonga islands, was first reported active in the mid-19th century, when an ephemeral island formed. An eruption in 1984 produced a 12-km-high eruption plume, large amounts of floating pumice, and an ephemeral 500 x 1,500 m island, with cliffs 30-50 m high that enclosed a water-filled crater. In 2006 an island-forming eruption produced widespread dacitic pumice rafts that drifted as far as Australia. Another island was built during a September-October 2022 eruption.

Information Contacts: Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Semisopochnoi (United States) — June 2023  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Semisopochnoi

United States

51.93°N, 179.58°E; summit elev. 1221 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Occasional explosions, ash deposits, and gas-and-steam plumes during December 2022-May 2023

Semisopochnoi is located in the western Aleutians, is 20-km-wide at sea level, and contains an 8-km-wide caldera. The three-peaked Mount Young (formerly Cerberus) was constructed within the caldera during the Holocene. Each of these peaks contains a summit crater; the lava flows on the N flank appear younger than those on the S side. The current eruption period began in early February 2021 and has more recently consisted of intermittent explosions and ash emissions (BGVN 47:12). This report updates activity during December 2022 through May 2023 using daily, weekly, and special reports from the Alaska Volcano Observatory (AVO). AVO monitors the volcano using local seismic and infrasound sensors, satellite data, web cameras, and remote infrasound and lightning networks.

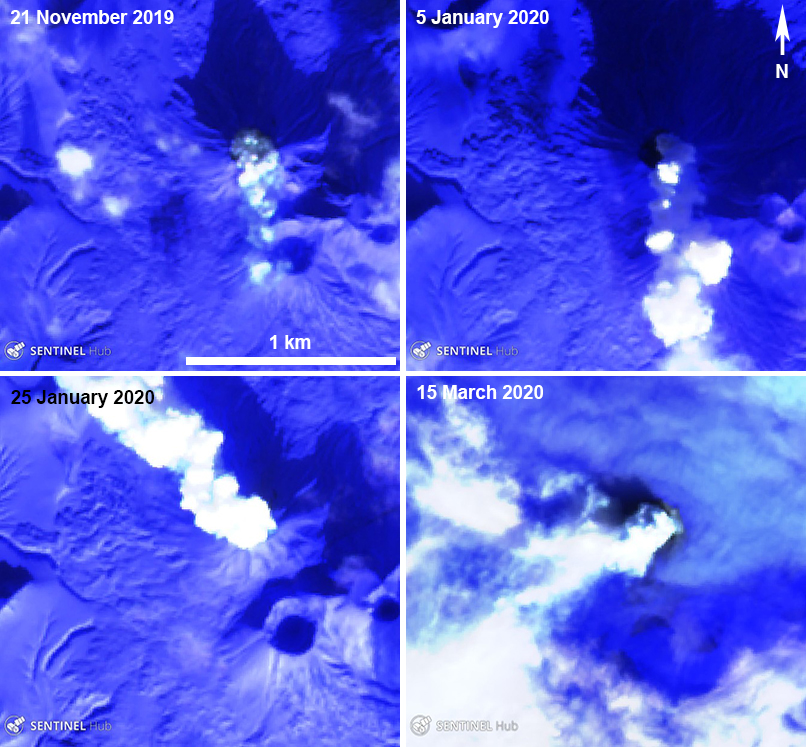

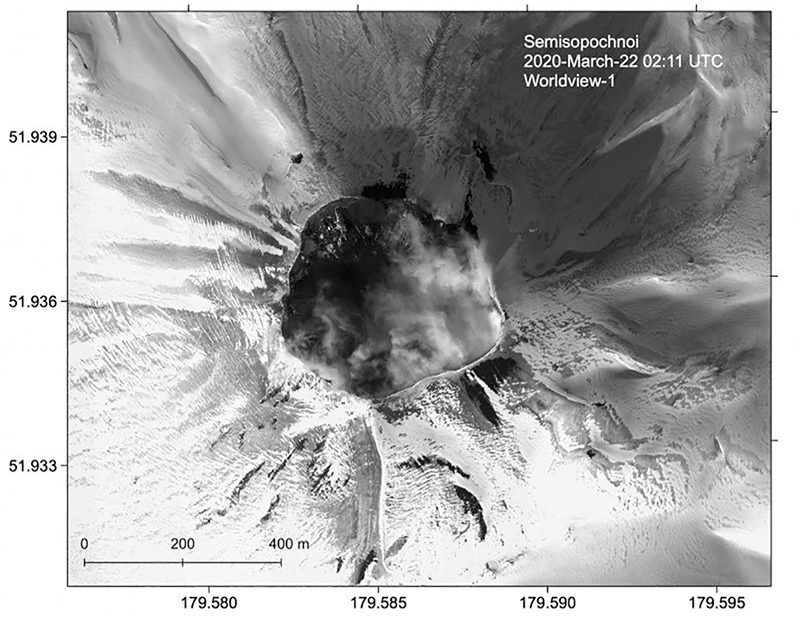

Activity during most of December 2022 was relatively quiet; according to AVO no eruptive or explosive activity was observed since 7 November 2022. Intermittent tremor and occasional small earthquakes were observed in geophysical data. Continuous gas-and-steam emissions were observed from the N crater of Mount Young in webcam images on clear weather days (figure 25). On 24 December, there was a slight increase in earthquake activity and several small possible explosion signals were detected in infrasound data. Eruptive activity resumed on 27 December at the N crater of Mount Young; AVO issued a Volcano Activity Notice (VAN) that reported minor ash deposits on the flanks of Mount Young that extended as far as 1 km from the vent, according to webcam images taken during 27-28 December (figure 26). No ash plumes were observed in webcam or satellite imagery, but a persistent gas-and-steam plume that might have contained some ash rose to 1.5 km altitude. As a result, AVO raised the Aviation Color Code (ACC) to Orange (the second highest level on a four-color scale) and the Volcano Alert Level (VAL) to Watch (the second highest level on a four-level scale). Possible explosions were detected during 21 December 2022 through 1 January 2023 and seismic tremor was recorded during 30-31 December.

During January 2023 eruptive activity continued at the active N crater of Mount Young. Minor ash deposits were observed on the flanks, extending about 2 km SSW, based on webcam images from 1 and 3 January. A possible explosion occurred during 1-2 January based on elevated seismicity recorded on local seismometers and an infrasound signal recorded minutes later by an array at Adak. Though no ash plumes were observed in webcam or satellite imagery, a persistent gas-and-steam plume rose to 1.5 km altitude that might have carried minor traces of ash. Ash deposits were accompanied by periods of elevated seismicity and infrasound signals from the local geophysical network, which AVO reported were likely due to weak explosive activity. Low-level explosive activity was also detected during 2-3 January, with minor gas-and-steam emissions and a new ash deposit that was visible in webcam images. Low-level explosive activity was detected in geophysical data during 4-5 January, with elevated seismicity and infrasound signals observed on local stations. Volcanic tremor was detected during 7-9 January and very weak explosive activity was detected in seismic and infrasound data on 9 January. Weak seismic and infrasound signals were recorded on 17 January, which indicated minor explosive activity, but no ash emissions were observed in clear webcam images; a gas-and-steam plume continued to rise to 1.5 km altitude. During 29-30 January, ash deposits near the summit were observed on fresh snow, according to webcam images.

The active N cone at Mount Young continued to produce a gas-and-steam plume during February, but no ash emissions or explosive events were detected. Seismicity remained elevated with faint tremor during early February. Gas-and-steam emissions from the N crater were observed in clear webcam images on 11-13 and 16 February; no explosive activity was detected in seismic, infrasound, or satellite data. Seismicity has also decreased, with no significant seismic tremor observed since 25 January. Therefore, the ACC was lowered to Yellow (the second lowest level on a four-color scale) and the VAL was lowered to Advisory (the second lowest level on a four-color scale) on 22 February.

Gas-and-steam emissions persisted during March from the N cone of Mount Young, based on clear webcam images. A few brief episodes of weak tremor were detected in seismic data, although seismicity decreased over the month. A gas-and-steam plume detected in satellite data extended 150 km on 18 March. Low-level ash emissions from the N cone at Mount Young were observed in several webcam images during 18-19 March, in addition to small explosions and volcanic tremor. The ACC was raised to Orange and the VAL increased to Watch on 19 March. A small explosion was detected in seismic and infrasound data on 21 March.

Low-level unrest continued during April, although cloudy weather often obscured views of the summit; periods of seismic tremor and local earthquakes were recorded. During 3-4 April a gas-and-steam plume was visible traveling more than 200 km overnight; no ash was evident in the plume, according to AVO. A gas-and-steam plume was observed during 4-6 April that extended 400 km but did not seem to contain ash. Small explosions were detected in seismic and infrasound data on 5 April. Occasional clear webcam images showed continuing gas-and-steam emissions rose from Mount Young, but no ash deposits were observed on the snow. On 19 April small explosions and tremor were detected in seismic and infrasound data. A period of seismic tremor was detected during 22-25 April, with possible weak explosions on 25 April. Ash deposits were visible near the crater rim, but it was unclear if these deposits were recent or due to older deposits.

Occasional small earthquakes were recorded during May, but there were no signs of explosive activity seen in geophysical data. Gas-and-steam emissions continued from the N crater of Mount Young, based on webcam images, and seismicity remained slightly elevated. A new, light ash deposit was visible during the morning of 5 May on fresh snow on the NW flank of Mount Young. During 10 May periods of volcanic tremor were observed. The ACC was lowered to Yellow and the VAL to Advisory on 17 May due to no additional evidence of activity.

Geologic Background. Semisopochnoi, the largest subaerial volcano of the western Aleutians, is 20 km wide at sea level and contains an 8-km-wide caldera. It formed as a result of collapse of a low-angle, dominantly basaltic volcano following the eruption of a large volume of dacitic pumice. The high point of the island is Anvil Peak, a double-peaked late-Pleistocene cone that forms much of the island's northern part. The three-peaked Mount Cerberus (renamed Mount Young in 2023) was constructed within the caldera during the Holocene. Each of the peaks contains a summit crater; lava flows on the N flank appear younger than those on the south side. Other post-caldera volcanoes include the symmetrical Sugarloaf Peak SSE of the caldera and Lakeshore Cone, a small cinder cone at the edge of Fenner Lake in the NE part of the caldera. Most documented eruptions have originated from Young, although Coats (1950) considered that both Sugarloaf and Lakeshore Cone could have been recently active.

Information Contacts: Alaska Volcano Observatory (AVO), a cooperative program of a) U.S. Geological Survey, 4200 University Drive, Anchorage, AK 99508-4667 USA (URL: https://avo.alaska.edu/), b) Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, PO Box 757320, Fairbanks, AK 99775-7320, USA, and c) Alaska Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys, 794 University Ave., Suite 200, Fairbanks, AK 99709, USA (URL: http://dggs.alaska.gov/).

Ambae

Vanuatu

15.389°S, 167.835°E; summit elev. 1496 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

New lava flow, ash plumes, and sulfur dioxide plumes during February-May 2023

Ambae, also known as Aoba, is a large basaltic shield volcano in Vanuatu. A broad pyroclastic cone containing three crater lakes (Manaro Ngoru, Voui, and Manaro Lakua) is located at the summit within the youngest of at least two nested calderas. Periodic phreatic and pyroclastic explosions have been reported since the 16th century. A large eruption more than 400 years ago resulted in a volcanic cone within the summit crater that is now filled by Lake Voui; the similarly sized Lake Manaro fills the western third of the caldera. The previous eruption ended in August 2022 that was characterized by gas-and-steam and ash emissions and explosions of wet tephra (BGVN 47:10). This report covers a new eruption during February through May 2023 that consisted of a new lava flow, ash plumes, and sulfur dioxide emissions, using information from the Vanuatu Meteorology and Geo-Hazards Department (VMGD) and satellite data.

During the reporting period, the Alert Level remained at a 2 (on a scale of 0-5), which has been in place since December 2021. Activity during October 2022 through March 2023 remained relatively low and mostly consisted of gas-and-steam emissions in Lake Voui. VMGD reported that at 1300 on 15 November a satellite image captured a strong amount of sulfur dioxide rising above the volcano (figure 99), and that seismicity slightly increased. The southern and northern part of the island reported a strong sulfur dioxide smell and heard explosions. On 20 February 2023 a gas-and-ash plume rose 1.3 km above the summit and drifted SSW, according to a webcam image (figure 100). Gas-and-steam and possibly ash emissions continued on 23 February and volcanic earthquakes were recorded by the seismic network.

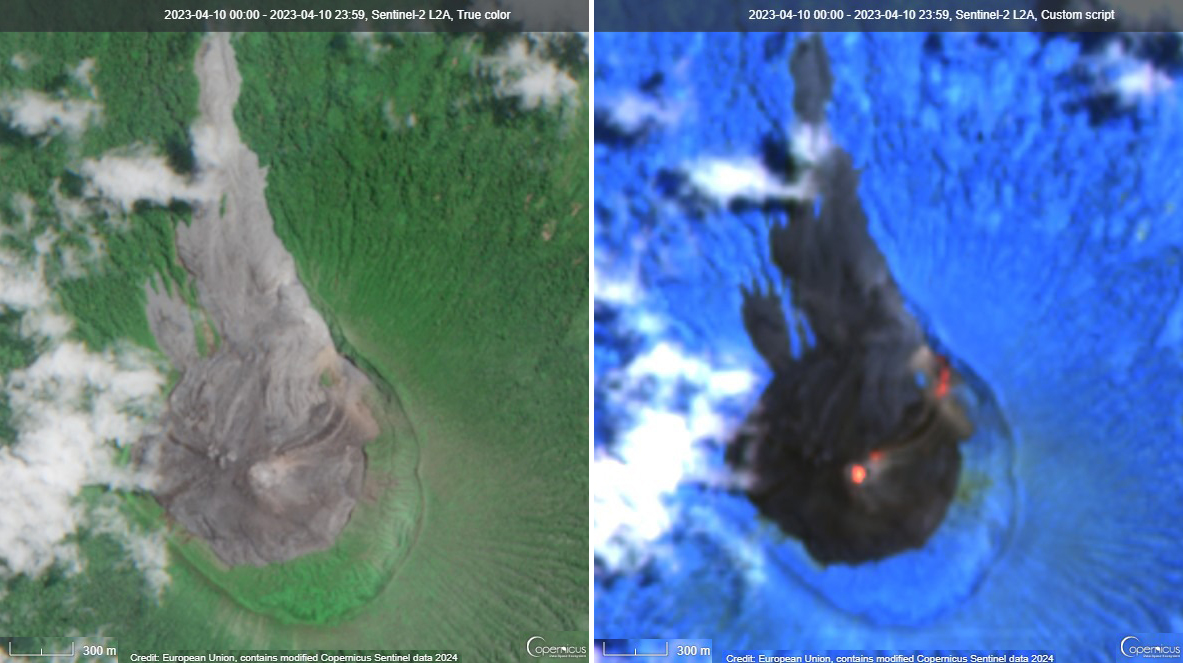

During April, volcanic earthquakes and gas-and-steam and ash emissions were reported from the cone in Lake Voui. VMGD reported that activity increased during 5-7 April; high gas-and-steam and ash plumes were visible, accompanied by nighttime incandescence. According to a Wellington VAAC report, a low-level ash plume rose as high as 2.5 km above the summit and drifted W and SW on 5 April, based on satellite imagery. Reports in Saratamata stated that a dark ash plume drifted to the WSW, but no loud explosion was heard. Webcam images from 2100 showed incandescence above the crater and reflected in the clouds. According to an aerial survey, field observations, and satellite data, water was no longer present in the lake. A lava flow was reported effusing from the vent and traveling N into the dry Lake Voui, which lasted three days. The next morning at 0745 on 6 April a gas-and-steam and ash plume rose 5.4 km above the summit and drifted ESE, based on information from VMGD (figure 101). The Wellington VAAC also reported that light ashfall was observed on the island. Intermittent gas-and-steam and ash emissions were visible on 7 April, some of which rose to an estimated 3 km above the summit and drifted E. Webcam images during 0107-0730 on 7 April showed continuing ash emissions. A gas-and-steam and ash plume rose 695 m above the summit crater at 0730 on 19 April and drifted ESE, based on a webcam image (figure 102).

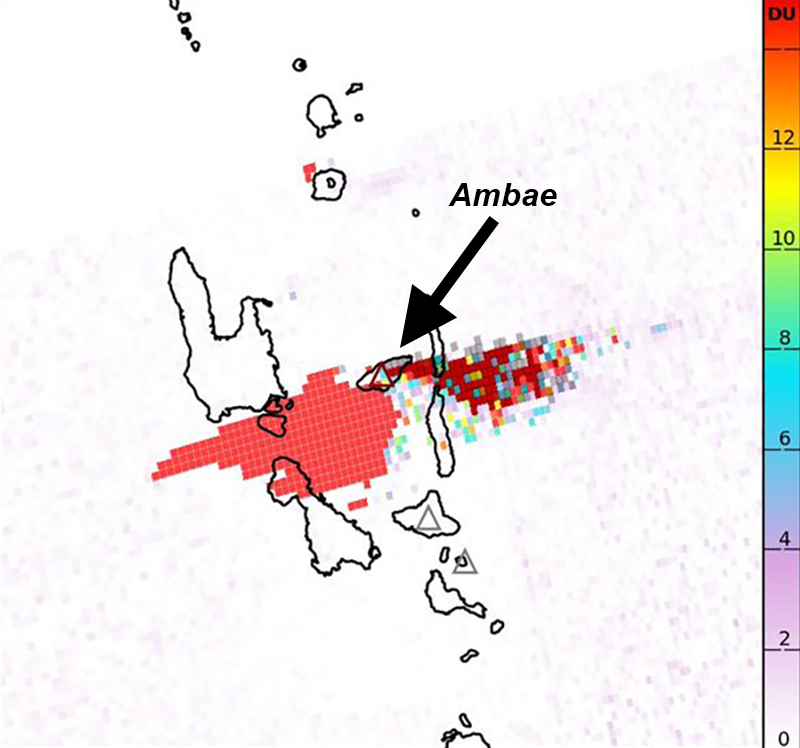

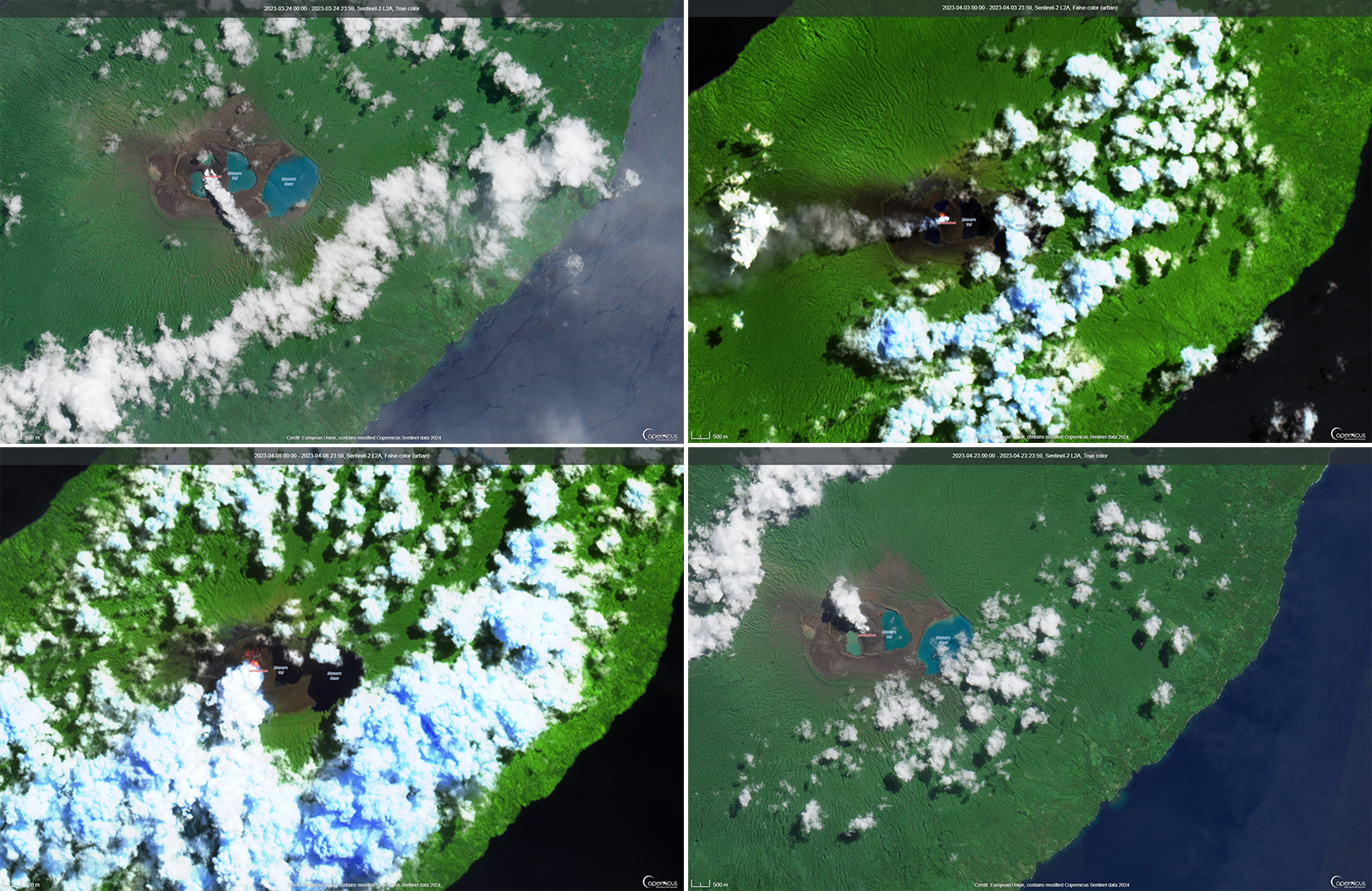

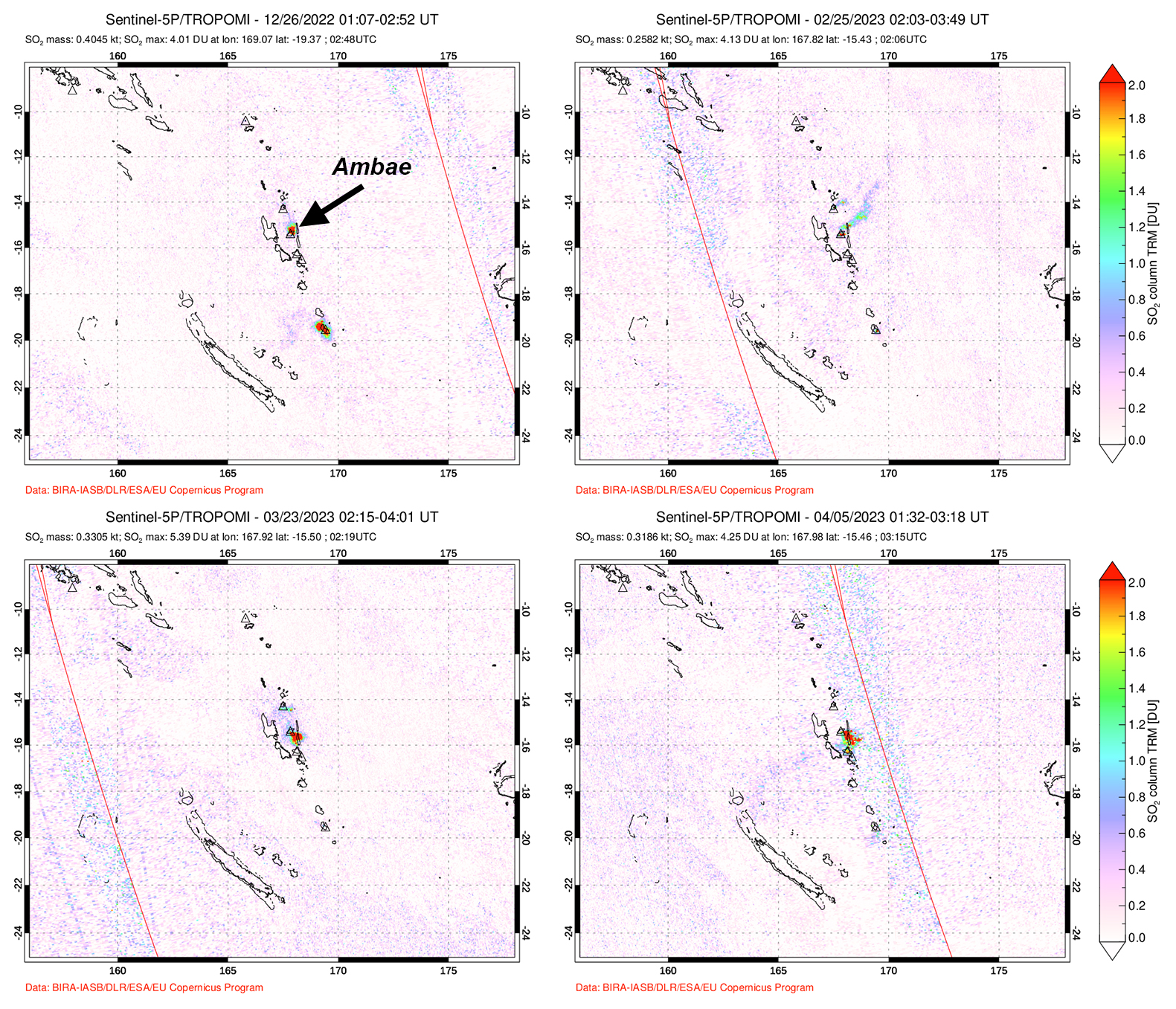

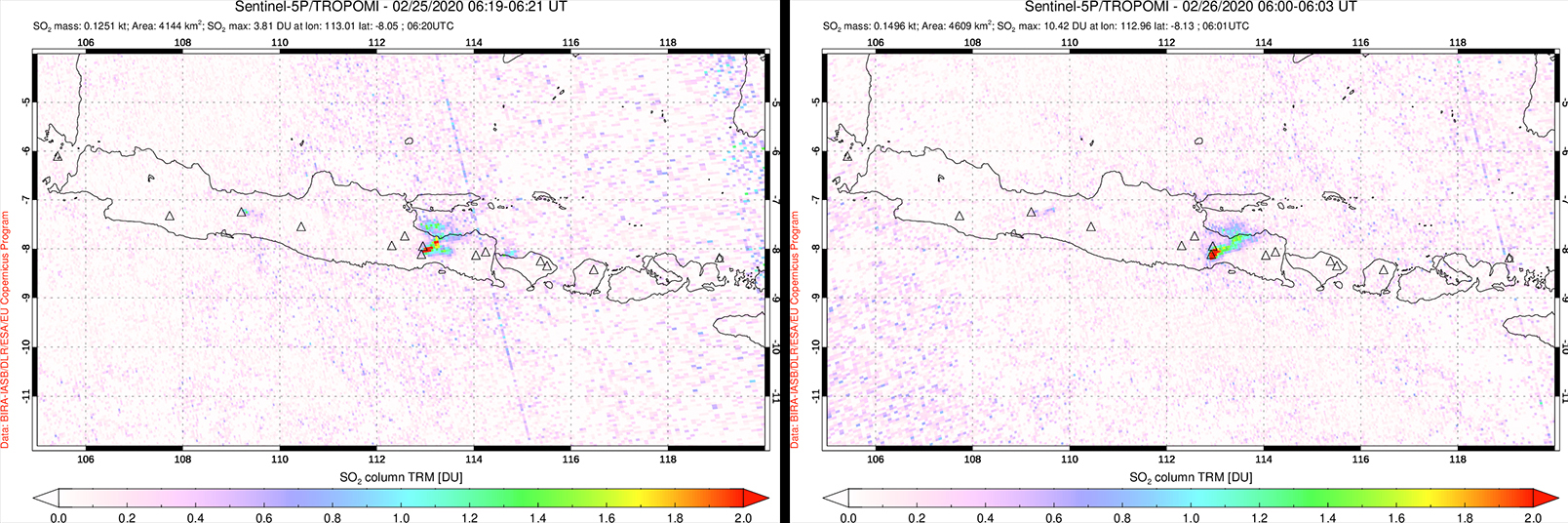

According to visual and infrared satellite data, water was visible in Lake Voui as late as 24 March 2023 (figure 103). The vent in the caldera showed a gas-and-steam plume drifted SE. On 3 April thermal activity was first detected, accompanied by a gas-and-ash plume that drifted W (figure 103). The lava flow moved N within the dry lake and was shown cooling by 8 April. By 23 April much of the water in the lake had returned. Occasional sulfur dioxide plumes were detected by the TROPOMI instrument on the Sentinel-5P satellite that exceeded 2 Dobson Units (DU) and drifted in different directions (figure 104).

Geologic Background. The island of Ambae, also known as Aoba, is a massive 2,500 km3 basaltic shield that is the most voluminous volcano of the New Hebrides archipelago. A pronounced NE-SW-trending rift zone with numerous scoria cones gives the 16 x 38 km island an elongated form. A broad pyroclastic cone containing three crater lakes (Manaro Ngoru, Voui, and Manaro Lakua) is located at the summit within the youngest of at least two nested calderas, the largest of which is 6 km in diameter. That large central edifice is also called Manaro Voui or Lombenben volcano. Post-caldera explosive eruptions formed the summit craters about 360 years ago. A tuff cone was constructed within Lake Voui (or Vui) about 60 years later. The latest known flank eruption, about 300 years ago, destroyed the population of the Nduindui area near the western coast.

Information Contacts: Geo-Hazards Division, Vanuatu Meteorology and Geo-Hazards Department (VMGD), Ministry of Climate Change Adaptation, Meteorology, Geo-Hazards, Energy, Environment and Disaster Management, Private Mail Bag 9054, Lini Highway, Port Vila, Vanuatu (URL: http://www.vmgd.gov.vu/, https://www.facebook.com/VanuatuGeohazardsObservatory/); Wellington Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre (VAAC), Meteorological Service of New Zealand Ltd (MetService), PO Box 722, Wellington, New Zealand (URL: http://www.metservice.com/vaac/, http://www.ssd.noaa.gov/VAAC/OTH/NZ/messages.html); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Global Sulfur Dioxide Monitoring Page, Atmospheric Chemistry and Dynamics Laboratory, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (NASA/GSFC), 8800 Greenbelt Road, Goddard, Maryland, USA (URL: https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Ibu

Indonesia

1.488°N, 127.63°E; summit elev. 1325 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Daily ash explosions continue, along with thermal anomalies in the crater, October 2022-May 2023

Persistent eruptive activity since April 2008 at Ibu, a stratovolcano on Indonesian’s Halmahera Island, has consisted of daily explosive ash emissions and plumes, along with observations of thermal anomalies (BGVN 47:04). The current eruption continued during October 2022-May 2023, described below, based on advisories issued by the Pusat Vulkanologi dan Mitigasi Bencana Geologi (PVMBG, also known as Indonesian Center for Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation, CVGHM), daily reports by MAGMA Indonesia (a PVMBG platform), and the Darwin Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre (VAAC), and various satellite data. The Alert Level during the reporting period remained at 2 (on a scale of 1-4), except raised briefly to 3 on 27 May, and the public was warned to stay at least 2 km away from the active crater and 3.5 km away on the N side of the volcano.

According to MAGMA Indonesia, during October 2022-May 2023, daily gray-and-white ash plumes of variable densities rose 200-1,000 m above the summit and drifted in multiple directions. On 30 October and 11 November, plumes rose a maximum of 2 km and 1.5 km above the summit, respectively (figures 42 and 43). According to the Darwin VAAC, discrete ash emissions on 13 November rose to 2.1 km altitude, or 800 m above the summit, and drifted W, and multiple ash emissions on 15 November rose 1.4 km above the summit and drifted NE. Occasional larger ash explosions through May 2023 prompted PVMBG to issue Volcano Observatory Notice for Aviation (VONA) alerts (table 6); the Aviation Color Code remained at Orange throughout this period.

Table 6. Volcano Observatory Notice for Aviation (VONA) ash plume alerts for Ibu issued by PVMBG during October 2022-May 2023. Maximum height above the summit was estimated by a ground observer. VONAs in January-May 2023 all described the ash plumes as dense.

| Date |

Time (local) |

Max height above summit |

Direction |

| 17 Oct 2022 |

0858 |

800 m |

SW |

| 18 Oct 2022 |

1425 |

800 m |

S |

| 19 Oct 2022 |

2017 |

600 m |

SW |

| 21 Oct 2022 |

0916 |

800 m |

NW |

| 16 Jan 2023 |

1959 |

600 m |

NE |

| 22 Jan 2023 |

0942 |

1,000 m |

E |

| 29 Jan 2023 |

2138 |

1,000 m |

E |

| 10 May 2023 |

0940 |

800 m |

NW |

| 10 May 2023 |

2035 |

600 m |

E |

| 21 May 2023 |

2021 |

600 m |

W |

| 21 May 2023 |

2140 |

1,000 m |

W |

| 29 May 2023 |

1342 |

800 m |

N |

| 31 May 2023 |

1011 |

1,000 m |

SW |

Sentinel-2 L1C satellite images throughout the reporting period show two, sometimes three persistent thermal anomalies in the summit crater, with the most prominent hotspot from the top of a cone within the crater. Clear views were more common during March-April 2023, when a vent and lava flows on the NE flank of the intra-crater cone could be distinguished (figure 44). White-to-grayish emissions were also observed during brief periods when weather clouds allowed clear views.

The MIROVA space-based volcano hotspot detection system recorded almost daily thermal anomalies throughout the reporting period, though cloud cover often interfered with detections. Data from imaging spectroradiometers aboard NASA’s Aqua and Terra satellites and processed using the MODVOLC algorithm (MODIS-MODVOLC) recorded hotspots on one day during October 2022 and December 2022, two days in April 2023, three days in November 2022 and May 2023, and four days in March 2023.

Geologic Background. The truncated summit of Gunung Ibu stratovolcano along the NW coast of Halmahera Island has large nested summit craters. The inner crater, 1 km wide and 400 m deep, has contained several small crater lakes. The 1.2-km-wide outer crater is breached on the N, creating a steep-walled valley. A large cone grew ENE of the summit, and a smaller one to the WSW has fed a lava flow down the W flank. A group of maars is located below the N and W flanks. The first observed and recorded eruption was a small explosion from the summit crater in 1911. Eruptive activity began again in December 1998, producing a lava dome that eventually covered much of the floor of the inner summit crater along with ongoing explosive ash emissions.

Information Contacts: Pusat Vulkanologi dan Mitigasi Bencana Geologi (PVMBG, also known as Indonesian Center for Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation, CVGHM), Jalan Diponegoro 57, Bandung 40122, Indonesia (URL: http://www.vsi.esdm.go.id/); MAGMA Indonesia (Multiplatform Application for Geohazard Mitigation and Assessment in Indonesia), Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral (URL: https://magma.esdm.go.id/v1); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/).

Dukono

Indonesia

1.6992°N, 127.8783°E; summit elev. 1273 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Continuing ash emissions, SO2 plumes, and thermal signals during October 2022-May 2023

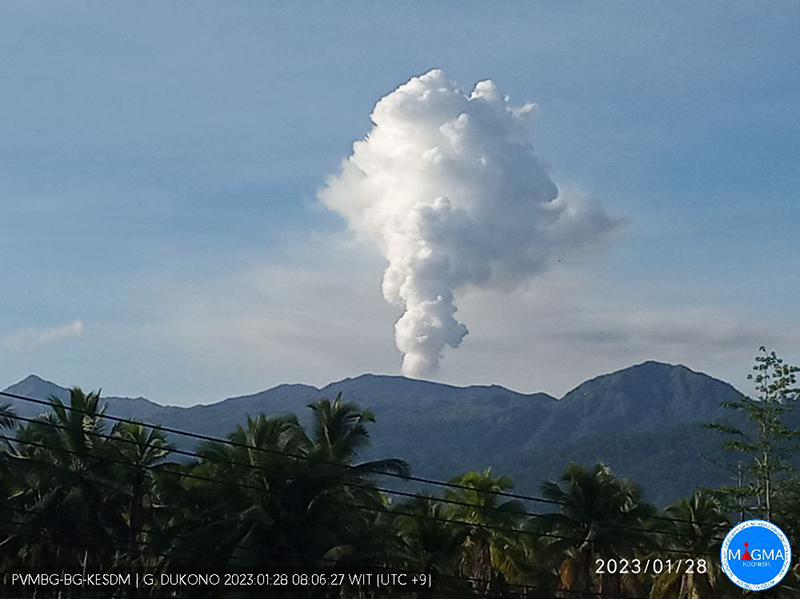

Dukono, a remote volcano on Indonesia’s Halmahera Island, has been erupting continuously since 1933, with frequent ash explosions and sulfur dioxide plumes (BGVN 46:11, 47:10). This activity continued during October 2022 through May 2023, based on reports from the Pusat Vulkanologi dan Mitigasi Bencana Geologi (PVMBG; also known as Indonesian Center for Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation, CVGHM), the Darwin Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre (VAAC), and satellite data. During this period, the Alert Level remained at 2 (on a scale of 1-4) and the public was warned to remain outside of the 2-km exclusion zone. The highest reported plume of the period reached 9.4 km above the summit on 14 November 2022.

According to MAGMA Indonesia (a platform developed by PVMBG), white, gray, or dark plumes of variable densities were observed almost every day during the reporting period, except when fog obscured the volcano (figure 33). Plumes generally rose 25-450 m above the summit, but rose as high as 700-800 m on several days, somewhat lower than the maximum heights reached earlier in 2022 when plumes reached as high as 1 km. However, the Darwin VAAC reported that on 14 November 2022, a discrete ash plume rose 9.4 km above the summit (10.7 km altitude), accompanied by a strong hotspot and a sulfur dioxide signal observed in satellite imagery; a continuous ash plume that day and through the 15th rose to 2.1-2.4 km altitude and drifted NE.

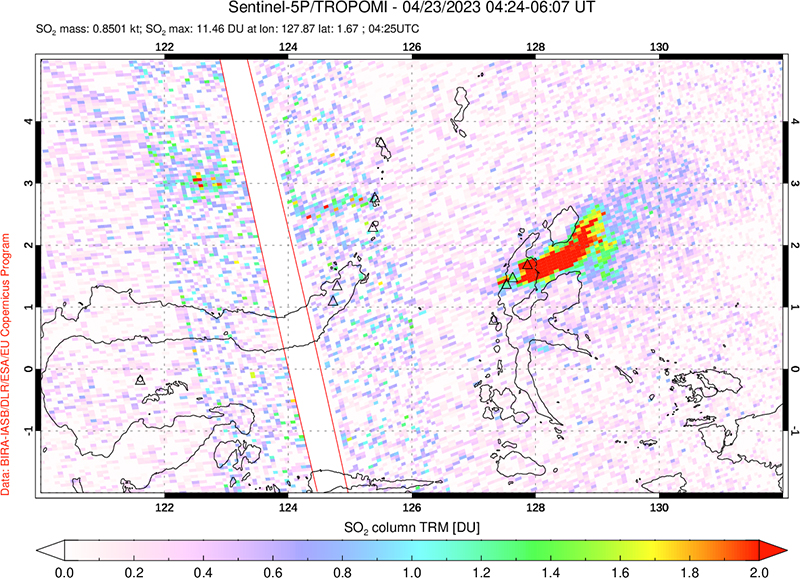

Sentinel-2 images were obscured by weather clouds almost every viewing day during the reporting period. However, the few reasonably clear images showed a hotspot and white or gray emissions and plumes. Strong SO2 plumes from Dukono were present on many days during October 2022-May 2023, as detected using the TROPOMI instrument on the Sentinel-5P satellite (figure 34).

Geologic Background. Reports from this remote volcano in northernmost Halmahera are rare, but Dukono has been one of Indonesia's most active volcanoes. More-or-less continuous explosive eruptions, sometimes accompanied by lava flows, have occurred since 1933. During a major eruption in 1550 CE, a lava flow filled in the strait between Halmahera and the N-flank Gunung Mamuya cone. This complex volcano presents a broad, low profile with multiple summit peaks and overlapping craters. Malupang Wariang, 1 km SW of the summit crater complex, contains a 700 x 570 m crater that has also been active during historical time.

Information Contacts: Pusat Vulkanologi dan Mitigasi Bencana Geologi (PVMBG, also known as Indonesian Center for Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation, CVGHM), Jalan Diponegoro 57, Bandung 40122, Indonesia (URL: http://www.vsi.esdm.go.id/); MAGMA Indonesia (Multiplatform Application for Geohazard Mitigation and Assessment in Indonesia), Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral (URL: https://magma.esdm.go.id/v1); Darwin Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre (VAAC), Bureau of Meteorology, Northern Territory Regional Office, PO Box 40050, Casuarina, NT 0811, Australia (URL: http://www.bom.gov.au/info/vaac/); NASA Global Sulfur Dioxide Monitoring Page, Atmospheric Chemistry and Dynamics Laboratory, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (NASA/GSFC), 8800 Greenbelt Road, Goddard, Maryland, USA (URL: https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/); Sentinel Hub Playground (URL: https://www.sentinel-hub.com/explore/sentinel-playground).

Sabancaya

Peru

15.787°S, 71.857°W; summit elev. 5960 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Explosions, gas-and-ash plumes, and thermal activity persist during November 2022-April 2023

Sabancaya is located in Peru, NE of Ampato and SE of Hualca Hualca. Eruptions date back to 1750 and have been characterized by explosions, phreatic activity, ash plumes, and ashfall. The current eruption period began in November 2016 and has more recently consisted of daily explosions, gas-and-ash plumes, and thermal activity (BGVN 47:11). This report updates activity during November 2022 through April 2023 using information from Instituto Geophysico del Peru (IGP) that use weekly activity reports and various satellite data.

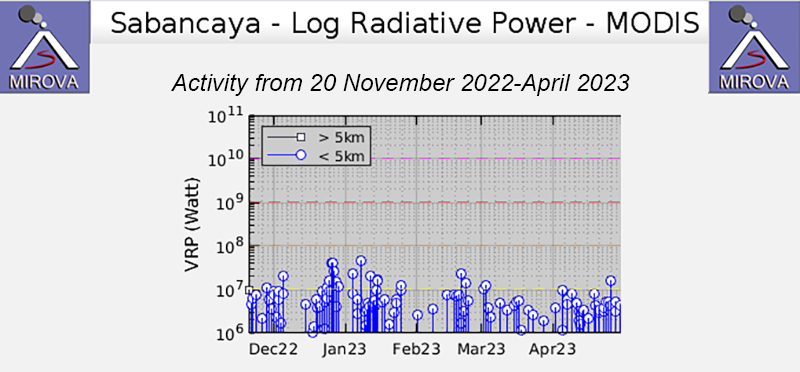

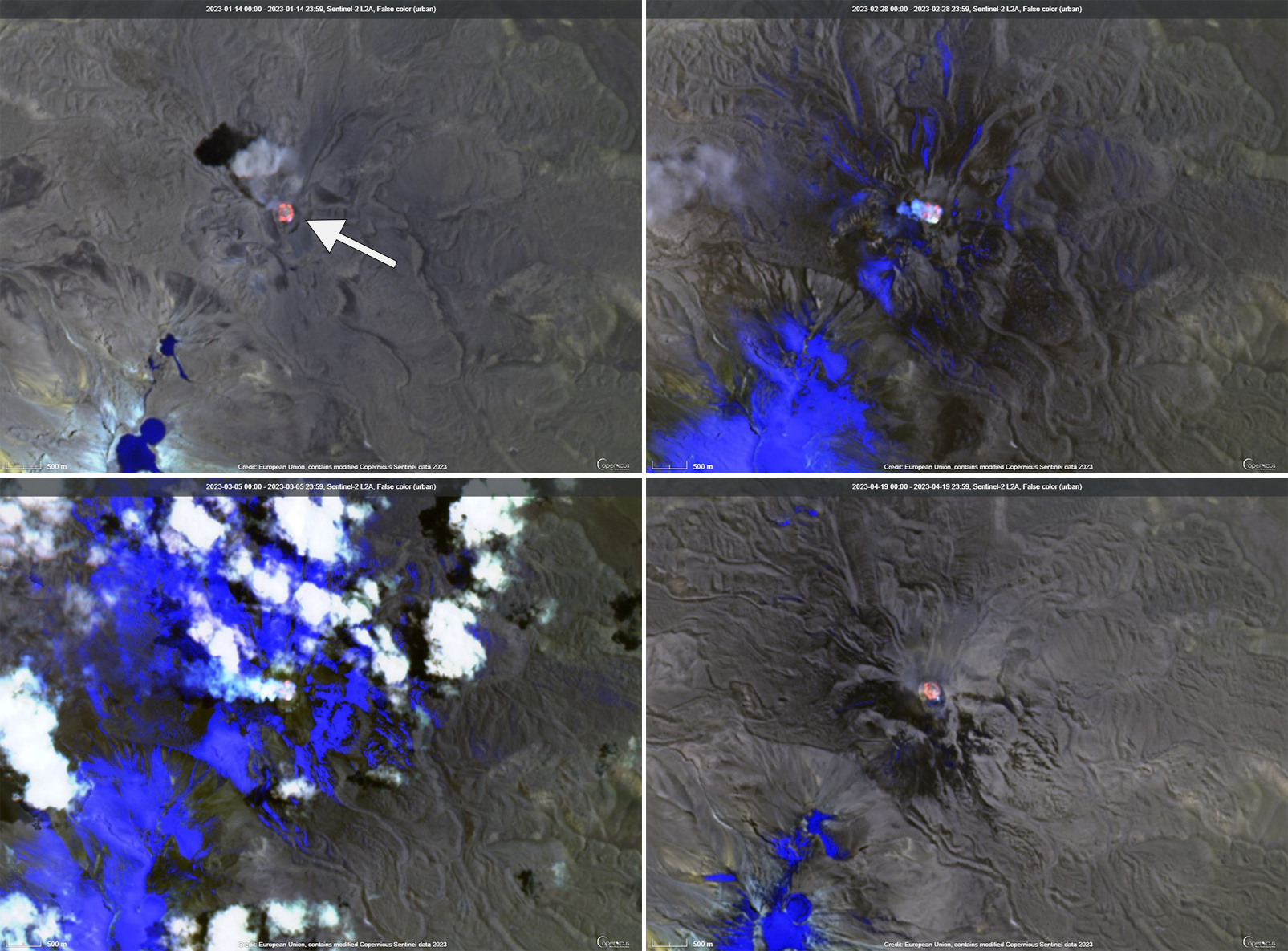

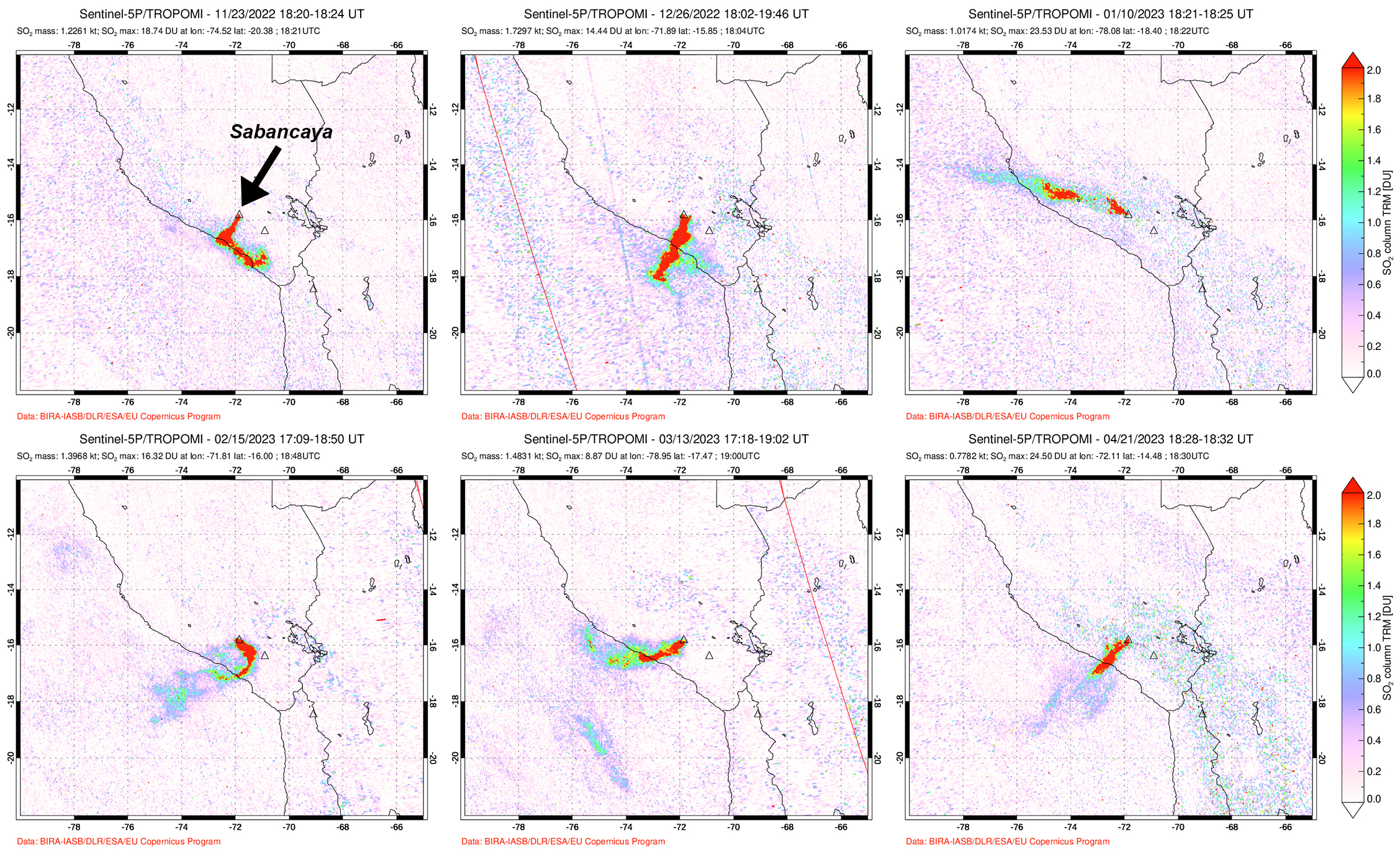

Intermittent low-to-moderate power thermal anomalies were reported by the MIROVA project during November 2022 through April 2023 (figure 119). There were few short gaps in thermal activity during mid-December 2022, late December-to-early January 2023, late January to mid-February, and late February. According to data recorded by the MODVOLC thermal algorithm, there were a total of eight thermal hotspots: three in November 2022, three in February 2023, one in March, and one in April. On clear weather days, some of this thermal anomaly was visible in infrared satellite imagery showing the active lava dome in the summit crater (figure 120). Almost daily moderate-to-strong sulfur dioxide plumes were recorded during the reporting period by the TROPOMI instrument on the Sentinel-5P satellite (figure 121). Many of these plumes exceeded 2 Dobson Units (DU) and drifted in multiple directions.

IGP reported that moderate activity during November and December 2022 continued; during November, an average number of explosions were reported each week: 30, 33, 36, and 35, and during December, it was 32, 40, 47, 52, and 67. Gas-and-ash plumes in November rose 3-3.5 km above the summit and drifted E, NE, SE, S, N, W, and SW. During December the gas-and-ash plumes rose 2-4 km above the summit and drifted in different directions. There were 1,259 volcanic earthquakes recorded during November and 1,693 during December. Seismicity also included volcano-tectonic-type events that indicate rock fracturing events. Slight inflation was observed in the N part of the volcano near Hualca Hualca (4 km N). Thermal activity was frequently reported in the crater at the active lava dome (figure 120).

Explosive activity continued during January and February 2023. The average number of explosions were reported each week during January (51, 50, 60, and 59) and February (43, 54, 51, and 50). Gas-and-ash plumes rose 1.6-2.9 km above the summit and drifted NW, SW, and W during January and rose 1.4-2.8 above the summit and drifted W, SW, E, SE, N, S, NW, and NE during February. IGP also detected 1,881 volcanic earthquakes during January and 1,661 during February. VT-type earthquakes were also reported. Minor inflation persisted near Hualca Hualca. Satellite imagery showed continuous thermal activity in the crater at the lava dome (figure 120).

During March, the average number of explosions each week was 46, 48, 31, 35, and 22 and during April, it was 29, 41, 31, and 27. Accompanying gas-and-ash plumes rose 1.7-2.6 km above the summit crater and drifted W, SW, NW, S, and SE during March. According to a Buenos Aires Volcano Ash Advisory Center (VAAC) notice, on 22 March at 1800 through 23 March an ash plume rose to 7 km altitude and drifted NW. By 0430 an ash plume rose to 7.6 km altitude and drifted W. On 24 and 26 March continuous ash emissions rose to 7.3 km altitude and drifted SW and on 28 March ash emissions rose to 7.6 km altitude. During April, gas-and-ash plumes rose 1.6-2.5 km above the summit and drifted W, SW, S, NW, NE, and E. Frequent volcanic earthquakes were recorded, with 1,828 in March and 1,077 in April, in addition to VT-type events. Thermal activity continued to be reported in the summit crater at the lava dome (figure 120).

Geologic Background. Sabancaya, located in the saddle NE of Ampato and SE of Hualca Hualca volcanoes, is the youngest of these volcanic centers and the only one to have erupted in historical time. The oldest of the three, Nevado Hualca Hualca, is of probable late-Pliocene to early Pleistocene age. The name Sabancaya (meaning "tongue of fire" in the Quechua language) first appeared in records in 1595 CE, suggesting activity prior to that date. Holocene activity has consisted of Plinian eruptions followed by emission of voluminous andesitic and dacitic lava flows, which form an extensive apron around the volcano on all sides but the south. Records of historical eruptions date back to 1750.

Information Contacts: Instituto Geofisico del Peru (IGP), Centro Vulcanológico Nacional (CENVUL), Calle Badajoz N° 169 Urb. Mayorazgo IV Etapa, Ate, Lima 15012, Perú (URL: https://www.igp.gob.pe/servicios/centro-vulcanologico-nacional/inicio); Buenos Aires Volcanic Ash Advisory Center (VAAC), Servicio Meteorológico Nacional-Fuerza Aérea Argentina, 25 de mayo 658, Buenos Aires, Argentina (URL: http://www.smn.gov.ar/vaac/buenosaires/inicio.php); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); NASA Global Sulfur Dioxide Monitoring Page, Atmospheric Chemistry and Dynamics Laboratory, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (NASA/GSFC), 8800 Greenbelt Road, Goddard MD 20771, USA (URL: https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Sheveluch

Russia

56.653°N, 161.36°E; summit elev. 3283 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Significant explosions destroyed part of the lava-dome complex during April 2023

Sheveluch (also spelled Shiveluch) in Kamchatka, has had at least 60 large eruptions during the last 10,000 years. The summit is truncated by a broad 9-km-wide caldera that is breached to the S, and many lava domes occur on the outer flanks. The lava dome complex was constructed within the large open caldera. Frequent collapses of the dome complex have produced debris avalanches; the resulting deposits cover much of the caldera floor. A major south-flank collapse during a 1964 Plinian explosion produced a scarp in which a “Young Sheveluch” dome began to form in 1980. Repeated episodes of dome formation and destruction since then have produced major and minor ash plumes, pyroclastic flows, block-and-ash flows, and “whaleback domes” of spine-like extrusions in 1993 and 2020 (BGVN 45:11). The current eruption period began in August 1999 and has more recently consisted of lava dome growth, explosions, ash plumes, and avalanches (BGVN 48:01). This report covers a significant explosive eruption during early-to-mid-April 2023 that generated a 20 km altitude ash plume, produced a strong sulfur dioxide plume, and destroyed part of the lava-dome complex; activity described during January through April 2023 use information primarily from the Kamchatka Volcanic Eruptions Response Team (KVERT) and various satellite data.

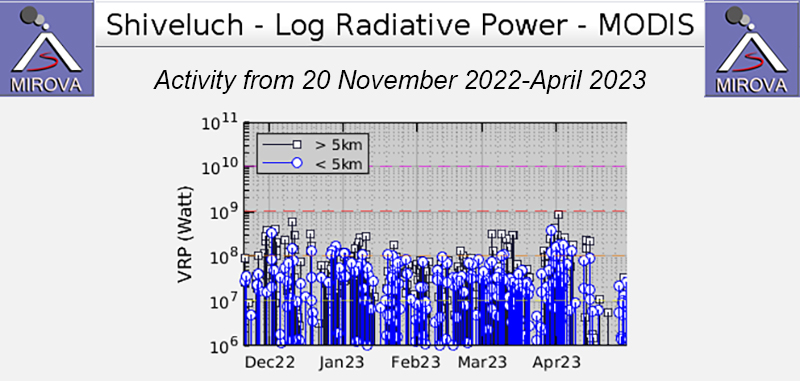

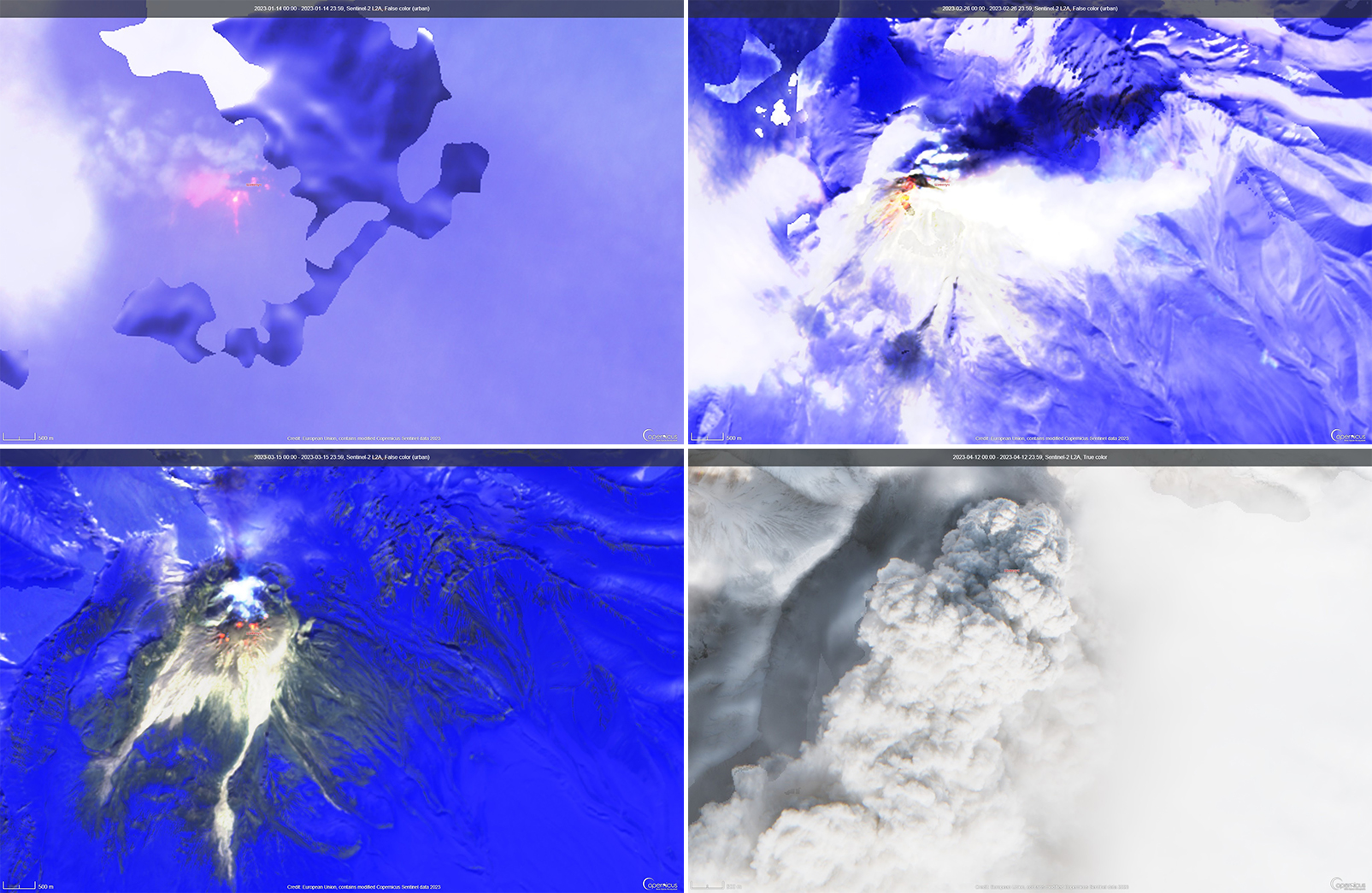

Satellite data. Activity during the majority of this reporting period was characterized by continued lava dome growth, strong fumarole activity, explosions, and hot avalanches. According to the MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, 140 hotspots were detected through the reporting period, with 33 recorded in January 2023, 29 in February, 44 in March, and 34 in April. Frequent strong thermal activity was recorded during January 2023 through April, according to the MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) graph and resulted from the continuously growing lava dome (figure 94). A slightly stronger pulse in thermal activity was detected in early-to-mid-April, which represented the significant eruption that destroyed part of the lava-dome complex. Thermal anomalies were also visible in infrared satellite imagery at the summit crater (figure 95).

During January 2023 KVERT reported continued growth of the lava dome, accompanied by strong fumarolic activity, incandescence from the lava dome, explosions, ash plumes, and avalanches. Satellite data showed a daily thermal anomaly over the volcano. Video data showed ash plumes associated with collapses at the dome that generated avalanches that in turn produced ash plumes rising to 3.5 km altitude and drifting 40 km W on 4 January and rising to 7-7.5 km altitude and drifting 15 km SW on 5 January. A gas-and-steam plume containing some ash that was associated with avalanches rose to 5-6 km altitude and extended 52-92 km W on 7 January. Explosions that same day produced ash plumes that rose to 7-7.5 km altitude and drifted 10 km W. According to a Volcano Observatory Notice for Aviation (VONA) issued at 1344 on 19 January, explosions produced an ash cloud that was 15 x 25 km in size and rose to 9.6-10 km altitude, drifting 21-25 km W; as a result, the Aviation Color Code (ACC) was raised to Red (the highest level on a four-color scale). Another VONA issued at 1635 reported that no more ash plumes were observed, and the ACC was lowered to Orange (the second highest level on a four-color scale). On 22 January an ash plume from collapses and avalanches rose to 5 km altitude and drifted 25 km NE and SW; ash plumes associated with collapses extended 70 km NE on 27 and 31 January.

Lava dome growth, fumarolic activity, dome incandescence, and occasional explosions and avalanches continued during February and March. A daily thermal anomaly was visible in satellite data. Explosions on 1 February generated ash plumes that rose to 6.3-6.5 km altitude and extended 15 km NE. Video data showed an ash cloud from avalanches rising to 5.5 km altitude and drifting 5 km SE on 2 February. Satellite data showed gas-and-steam plumes containing some ash rose to 5-5.5 km altitude and drifted 68-110 km ENE and NE on 6 February, to 4.5-5 km altitude and drifted 35 km WNW on 22 February, and to 3.7-4 km altitude and drifted 47 km NE on 28 February. Scientists from the Kamchatka Volcanological Station (KVS) went on a field excursion on 25 February to document the growing lava dome, and although it was cloudy most of the day, nighttime incandescence was visible. Satellite data showed an ash plume extending up to 118 km E during 4-5 March. Video data from 1150 showed an ash cloud from avalanches rose to 3.7-5.5 km altitude and drifted 5-10 km ENE and E on 5 March. On 11 March an ash plume drifted 62 km E. On 27 March ash plumes rose to 3.5 km altitude and drifted 100 km E. Avalanches and constant incandescence at the lava dome was focused on the E and NE slopes on 28 March. A gas-and-steam plume containing some ash rose to 3.5 km altitude and moved 40 km E on 29 March. Ash plumes on 30 March rose to 3.5-3.7 km altitude and drifted 70 km NE.

Similar activity continued during April, with lava dome growth, strong fumarolic activity, incandescence in the dome, occasional explosions, and avalanches. A thermal anomaly persisted throughout the month. During 1-4 April weak ash plumes rose to 2.5-3 km altitude and extended 13-65 km SE and E.

Activity during 11 April 2023. The Institute of Volcanology and Seismology, Far Eastern Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences (IVS FEB RAS) reported a significant increase in seismicity around 0054 on 11 April, as reported by strong explosions detected on 11 April beginning at 0110 that sent ash plumes up to 7-10 km altitude and extended 100-435 km W, WNW, NNW, WSW, and SW. According to a Tokyo VAAC report the ash plume rose to 15.8 km altitude. By 0158 the plume extended over a 75 x 100 km area. According to an IVS FEB RAS report, the eruptive column was not vertical: the initial plume at 0120 on 11 April deviated to the NNE, at 0000 on 12 April, it drifted NW, and by 1900 it drifted SW. KVS reported that significant pulses of activity occurred at around 0200, 0320, and then a stronger phase around 0600. Levin Dmitry took a video from near Békés (3 km away) at around 0600 showing a rising plume; he also reported that a pyroclastic flow traveled across the road behind him as he left the area. According to IVS FEB RAS, the pyroclastic flow traveled several kilometers SSE, stopping a few hundred meters from a bridge on the road between Klyuchi and Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky.

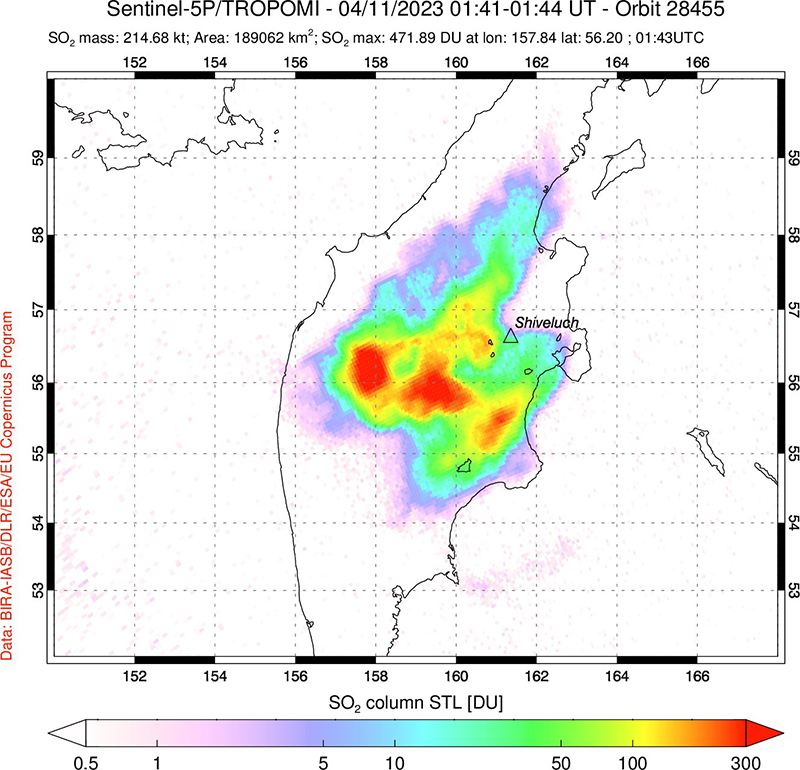

Ashfall was first observed in Klyuchi (45 km SW) at 0630, and a large, black ash plume blocked light by 0700. At 0729 KVERT issued a Volcano Observatory Notice for Aviation (VONA) raising the Aviation Color Code to Red (the highest level on a four-color scale). It also stated that a large ash plume had risen to 10 km altitude and drifted 100 km W. Near-constant lightning strikes were reported in the plume and sounds like thunderclaps were heard until about 1000. According to IVS FEB RAS the cloud was 200 km long and 76 km wide by 0830, and was spreading W at altitudes of 6-12 km. In the Klyuchi Village, the layer of both ash and snow reached 8.5 cm (figure 96); ashfall was also reported in Kozyrevsk (112 km SW) at 0930, Mayskoye, Anavgay, Atlasovo, Lazo, and Esso. Residents in Klyuchi reported continued darkness and ashfall at 1100. In some areas, ashfall was 6 cm deep and some residents reported dirty water coming from their plumbing. According to IVS FEB RAS, an ash cloud at 1150 rose to 5-20 km altitude and was 400 km long and 250 km wide, extending W. A VONA issued at 1155 reported that ash had risen to 10 km and drifted 340 km NNW and 240 km WSW. According to Simon Carn (Michigan Technological University), about 0.2 Tg of sulfur dioxide in the plume was measured in a satellite image from the TROPOMI instrument on the Sentinel-5P satellite acquired at 1343 that covered an area of about 189,000 km2 (figure 97). Satellite data at 1748 showed an ash plume that rose to 8 km altitude and drifted 430 km WSW and S, according to a VONA.

Activity during 12-15 April 2023. On 12 April at 0730 satellite images showed ash plumes rose to 7-8 km altitude and extended 600 km SW, 1,050 km ESE, and 1,300-3,000 km E. By 1710 that day, the explosions weakened. According to news sources, the ash-and-gas plumes drifted E toward the Aleutian Islands and reached the Gulf of Alaska by 13 April, causing flight disruptions. More than 100 flights involving Alaska airspace were cancelled due to the plume. Satellite data showed ash plumes rising to 4-5.5 km altitude and drifted 400-415 km SE and ESE on 13 April. KVS volcanologists observed the pyroclastic flow deposits and noted that steam rose from downed, smoldering trees. They also noted that the deposits were thin with very few large fragments, which differed from previous flows. The ash clouds traveled across the Pacific Ocean. Flight cancellations were also reported in NW Canada (British Columbia) during 13-14 April. During 14-15 April ash plumes rose to 6 km altitude and drifted 700 km NW.

Alaskan flight schedules were mostly back to normal by 15 April, with only minor delays and far less cancellations; a few cancellations continued to be reported in Canada. Clear weather on 15 April showed that most of the previous lava-dome complex was gone and a new crater roughly 1 km in diameter was observed (figure 98); gas-and-steam emissions were rising from this crater. Evidence suggested that there had been a directed blast to the SE, and pyroclastic flows traveled more than 20 km. An ash plume rose to 4.5-5.2 km altitude and drifted 93-870 km NW on 15 April.

Activity during 16-30 April 2023. Resuspended ash was lifted by the wind from the slopes and rose to 4 km altitude and drifted 224 km NW on 17 April. KVERT reported a plume of resuspended ash from the activity during 10-13 April on 19 April that rose to 3.5-4 km altitude and drifted 146-204 km WNW. During 21-22 April a plume stretched over the Scandinavian Peninsula. A gas-and-steam plume containing some ash rose to 3-3.5 km altitude and drifted 60 km SE on 30 April. A possible new lava dome was visible on the W slope of the volcano on 29-30 April (figure 99); satellite data showed two thermal anomalies, a bright one over the existing lava dome and a weaker one over the possible new one.

References. Girina, O., Loupian, E., Horvath, A., Melnikov, D., Manevich, A., Nuzhdaev, A., Bril, A., Ozerov, A., Kramareva, L., Sorokin, A., 2023, Analysis of the development of the paroxysmal eruption of Sheveluch volcano on April 10–13, 2023, based on data from various satellite systems, ??????????? ???????? ??? ?? ???????, 20(2).

Geologic Background. The high, isolated massif of Sheveluch volcano (also spelled Shiveluch) rises above the lowlands NNE of the Kliuchevskaya volcano group. The 1,300 km3 andesitic volcano is one of Kamchatka's largest and most active volcanic structures, with at least 60 large eruptions during the Holocene. The summit of roughly 65,000-year-old Stary Shiveluch is truncated by a broad 9-km-wide late-Pleistocene caldera breached to the south. Many lava domes occur on its outer flanks. The Molodoy Shiveluch lava dome complex was constructed during the Holocene within the large open caldera; Holocene lava dome extrusion also took place on the flanks of Stary Shiveluch. Widespread tephra layers from these eruptions have provided valuable time markers for dating volcanic events in Kamchatka. Frequent collapses of dome complexes, most recently in 1964, have produced debris avalanches whose deposits cover much of the floor of the breached caldera.

Information Contacts: Kamchatka Volcanic Eruptions Response Team (KVERT), Far Eastern Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, 9 Piip Blvd., Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, 683006, Russia (URL: http://www.kscnet.ru/ivs/kvert/); Institute of Volcanology and Seismology, Far Eastern Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences (IVS FEB RAS), 9 Piip Blvd., Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky 683006, Russia (URL: http://www.kscnet.ru/ivs/eng/); Kamchatka Volcanological Station, Kamchatka Branch of Geophysical Survey, (KB GS RAS), Klyuchi, Kamchatka Krai, Russia (URL: http://volkstat.ru/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/); Kam 24 News Agency, 683032, Kamchatka Territory, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, Vysotnaya St., 2A (URL: https://kam24.ru/news/main/20230411/96657.html#.Cj5Jrky6.dpuf); Simon Carn, Geological and Mining Engineering and Sciences, Michigan Technological University, 1400 Townsend Drive, Houghton, MI 49931, USA (URL: http://www.volcarno.com/, Twitter: @simoncarn).

Bezymianny

Russia

55.972°N, 160.595°E; summit elev. 2882 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Explosions, ash plumes, lava flows, and avalanches during November 2022-April 2023

Bezymianny is located on the Kamchatka Peninsula of Russia as part of the Klyuchevskoy volcano group. Historic eruptions began in 1955 and have been characterized by dome growth, explosions, pyroclastic flows, ash plumes, and ashfall. During the 1955-56 eruption a large open crater was formed by collapse of the summit and an associated lateral blast. Subsequent episodic but ongoing lava-dome growth, accompanied by intermittent explosive activity and pyroclastic flows, has largely filled the 1956 crater. The current eruption period began in December 2016 and more recent activity has consisted of strong explosions, ash plumes, and thermal activity (BGVN 47:11). This report covers activity during November 2022 through April 2023, based on weekly and daily reports from the Kamchatka Volcano Eruptions Response Team (KVERT) and satellite data.

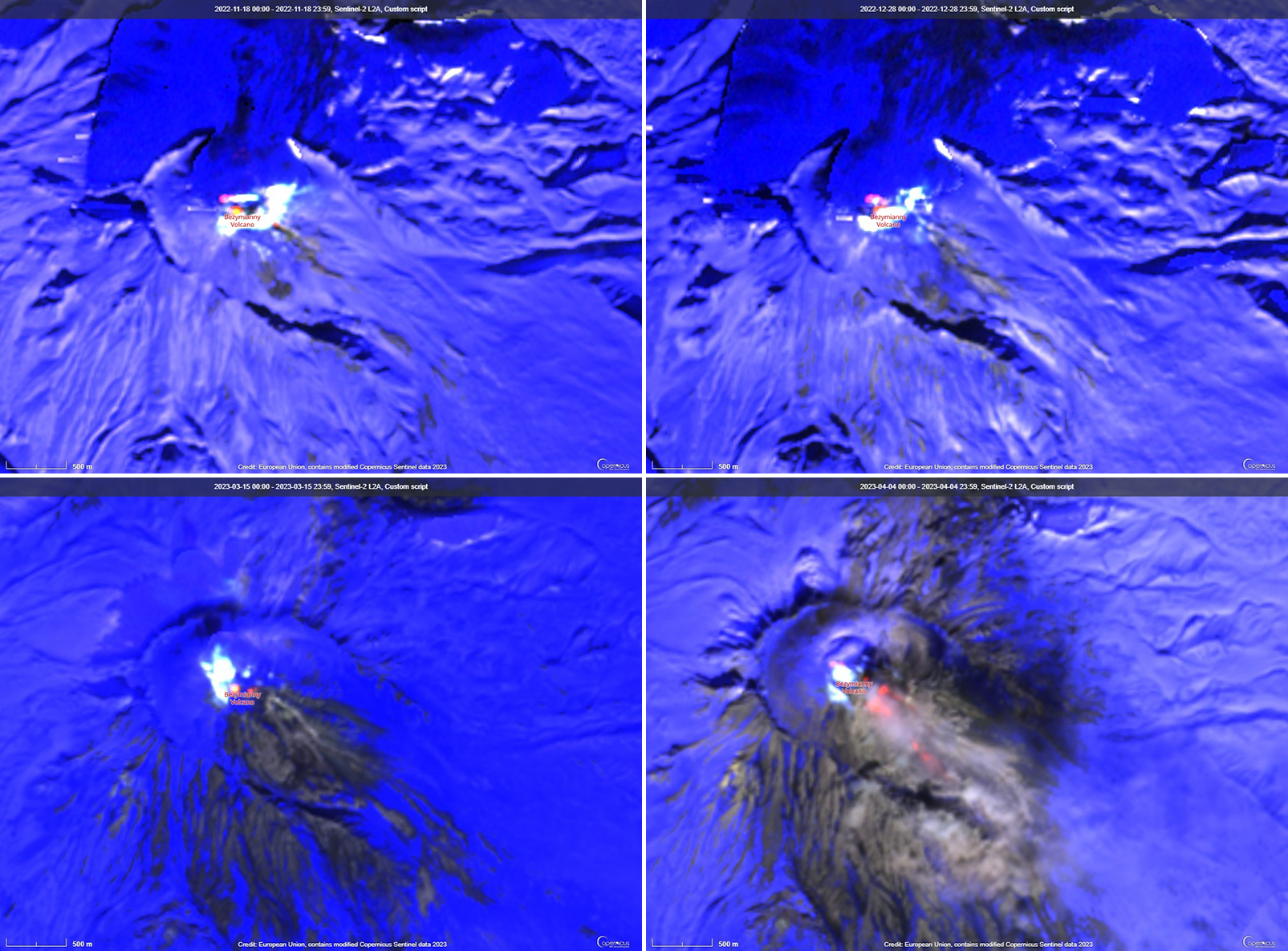

Activity during November and March 2023 was relatively low and mostly consisted of gas-and-steam emissions, occasional small collapses that generated avalanches along the lava dome slopes, and a persistent thermal anomaly over the volcano that was observed in satellite data on clear weather days. According to the Tokyo VAAC and KVERT, an explosion produced an ash plume that rose to 6 km altitude and drifted 25 km NE at 1825 on 29 March.

Gas-and-steam emissions, collapses generating avalanches, and thermal activity continued during April. According to two Volcano Observatory Notice for Aviation (VONA) issued on 2 and 6 April (local time) ash plumes rose to 3 km and 3.5-3.8 km altitude and drifted 35 km E and 140 km E, respectively. Satellite data from KVERT showed weak ash plumes extending up to 550 km E on 2 and 5-6 April.

A VONA issued at 0843 on 7 April described an ash plume that rose to 4.5-5 km altitude and drifted 250 km ESE. Later that day at 1326 satellite data showed an ash plume that rose to 5.5-6 km altitude and drifted 150 km ESE. A satellite image from 1600 showed an ash plume extending as far as 230 km ESE; KVERT noted that ash emissions were intensifying, likely due to avalanches from the growing lava dome. The Aviation Color Code (ACC) was raised to Red (the highest level on a four-color scale). At 1520 satellite data showed an ash plume rising to 5-5.5 km altitude and drifting 230 km ESE. That same day, Kamchatka Volcanological Station (KVS) volcanologists traveled to Ambon to collect ash; they reported that a notable eruption began at 1730, and within 20 minutes a large ash plume rose to 10 km altitude and drifted NW. KVERT reported that the strong explosive phase began at 1738. Video and satellite data taken at 1738 showed an ash plume that rose to 10-12 km altitude and drifted up to 2,800 km SE and E. Explosions were clearly audible 20 km away for 90 minutes, according to KVS. Significant amounts of ash fell at the Apakhonchich station, which turned the snow gray; ash continued to fall until the morning of 8 April. In a VONA issued at 0906 on 8 April, KVERT stated that the explosive eruption had ended; ash plumes had drifted 2,000 km E. The ACC was lowered to Orange (the third highest level on a four-color scale). The KVS team saw a lava flow on the active dome once the conditions were clear that same day (figure 53). On 20 April lava dome extrusion was reported; lava flows were noted on the flanks of the dome, and according to KVERT satellite data, a thermal anomaly was observed in the area. The ACC was lowered to Yellow (the second lowest on a four-color scale).

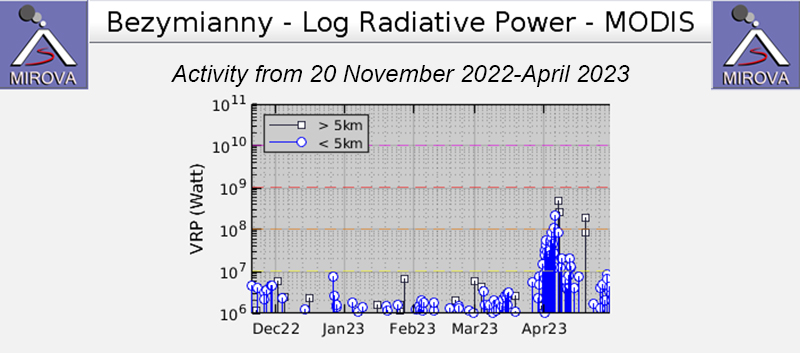

Satellite data showed an increase in thermal activity beginning in early April 2023. A total of 31 thermal hotspots were detected by the MODVOLC thermal algorithm on 4, 5, 7, and 12 April 2023. The elevated thermal activity resulted from an increase in explosive activity and the start of an active lava flow. The MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) volcano hotspot detection system based on the analysis of MODIS data also showed a pulse in thermal activity during the same time (figure 54). Infrared satellite imagery captured a continuous thermal anomaly at the summit crater, often accompanied by white gas-and-steam emissions (figure 55). On 4 April 2023 an active lava flow was observed descending the SE flank.

Geologic Background. The modern Bezymianny, much smaller than its massive neighbors Kamen and Kliuchevskoi on the Kamchatka Peninsula, was formed about 4,700 years ago over a late-Pleistocene lava-dome complex and an edifice built about 11,000-7,000 years ago. Three periods of intensified activity have occurred during the past 3,000 years. The latest period, which was preceded by a 1,000-year quiescence, began with the dramatic 1955-56 eruption. This eruption, similar to that of St. Helens in 1980, produced a large open crater that was formed by collapse of the summit and an associated lateral blast. Subsequent episodic but ongoing lava-dome growth, accompanied by intermittent explosive activity and pyroclastic flows, has largely filled the 1956 crater.

Information Contacts: Kamchatka Volcanic Eruptions Response Team (KVERT), Far Eastern Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, 9 Piip Blvd., Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, 683006, Russia (URL: http://www.kscnet.ru/ivs/kvert/); Kamchatka Volcanological Station, Kamchatka Branch of Geophysical Survey, (KB GS RAS), Klyuchi, Kamchatka Krai, Russia (URL: http://volkstat.ru/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Chikurachki

Russia

50.324°N, 155.461°E; summit elev. 1781 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

New explosive eruption during late January-early February 2023

Chikurachki, located on Paramushir Island in the northern Kuriles, has had Plinian eruptions during the Holocene. Lava flows have reached the sea and formed capes on the NW coast; several young lava flows are also present on the E flank beneath a scoria deposit. Reported eruptions date back to 1690, with the most recent eruption period occurring during January through October 2022, characterized by occasional explosions, ash plumes, and thermal activity (BGVN 47:11). This report covers a new eruptive period during January through February 2023 that consisted of ash explosions and ash plumes, based on information from the Kamchatka Volcanic Eruptions Response Team (KVERT) and satellite data.

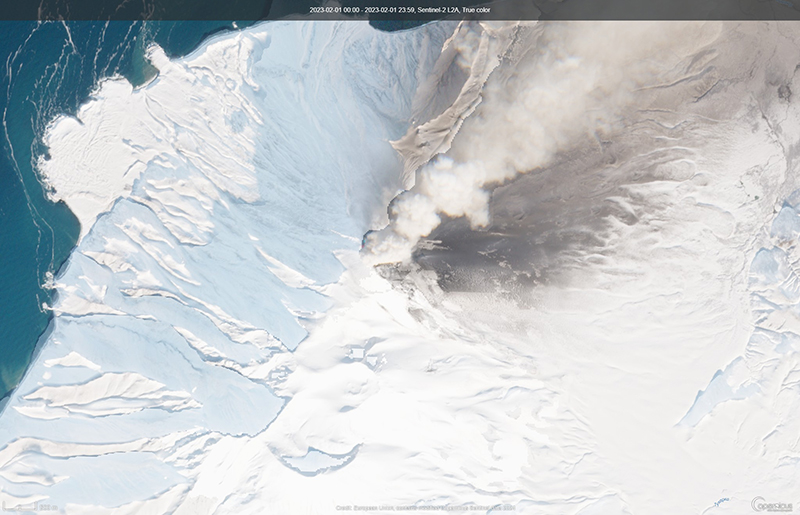

According to reports from KVERT, an explosive eruption began around 0630 on 29 January. Explosions generated ash plumes that rose to 3-3.5 km altitude and drifted 6-75 km SE and E, based on satellite data. As a result, the Aviation Color Code (ACC) was raised to Orange (the second highest level on a four-color scale). At 1406 and 1720 ash plumes were identified in satellite images that rose to 4.3 km altitude and extended 70 km E. By 2320 the ash plume had dissipated. A thermal anomaly was visible at the volcano on 31 January, according to a satellite image, and an ash plume was observed drifting 66 km NE.

Occasional explosions and ash plumes continued during early February. At 0850 on 1 February an ash plume rose to 3.5 km altitude and drifted 35 km NE. Satellite data showed an ash plume that rose to 3.2-3.5 km altitude and drifted 50 km NE at 1222 later that day (figure 22). A thermal anomaly was detected over the volcano during 5-6 February and ash plumes drifted as far as 125 km SE, E, and NE. Explosive events were reported at 0330 on 6 February that produced ash plumes rising to 4-4.5 km altitude and drifting 72-90 km N, NE, and ENE. KVERT noted that the last gas-and steam plume that contained some ash was observed on 8 February and drifted 55 km NE before the explosive eruption ended. The ACC was lowered to Yellow and then Green (the lowest level on a four-color scale) on 18 February.

Geologic Background. Chikurachki, the highest volcano on Paramushir Island in the northern Kuriles, is a relatively small cone constructed on a high Pleistocene edifice. Oxidized basaltic-to-andesitic scoria deposits covering the upper part of the young cone give it a distinctive red color. Frequent basaltic Plinian eruptions have occurred during the Holocene. Lava flows have reached the sea and formed capes on the NW coast; several young lava flows are also present on the E flank beneath a scoria deposit. The Tatarinov group of six volcanic centers is located immediately to the south, and the Lomonosov cinder cone group, the source of an early Holocene lava flow that reached the saddle between it and Fuss Peak to the west, lies at the southern end of the N-S-trending Chikurachki-Tatarinov complex. In contrast to the frequently active Chikurachki, the Tatarinov centers are extensively modified by erosion and have a more complex structure. Tephrochronology gives evidence of an eruption around 1690 CE from Tatarinov, although its southern cone contains a sulfur-encrusted crater with fumaroles that were active along the margin of a crater lake until 1959.

Information Contacts: Kamchatka Volcanic Eruptions Response Team (KVERT), Far East Division, Russian Academy of Sciences, 9 Piip Blvd., Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, 683006, Russia (URL: http://www.kscnet.ru/ivs/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Search Bulletin Archive by Publication Date

Select a month and year from the drop-downs and click "Show Issue" to have that issue displayed in this tab.

The default month and year is the latest issue available.

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network - Volume 45, Number 04 (April 2020)

Managing Editor: Edward Venzke

Etna (Italy)

Strombolian explosions and ash emissions continue, October 2019-March 2020

Fuego (Guatemala)

Ongoing ash explosions, block avalanches, and intermittent lava flows

Merapi (Indonesia)

Explosions produced ash plumes, ashfall, and pyroclastic flows during October 2019-March 2020

Popocatepetl (Mexico)

Dome growth and destruction continues along with ash emissions and ejecta, September 2019-February 2020

Rincon de la Vieja (Costa Rica)

Weak phreatic explosions during August 2019-March 2020; ash and lahars reported in late January

Santa Maria (Guatemala)

Daily explosions with ash plumes and block avalanches continue, September 2019-February 2020

Semeru (Indonesia)

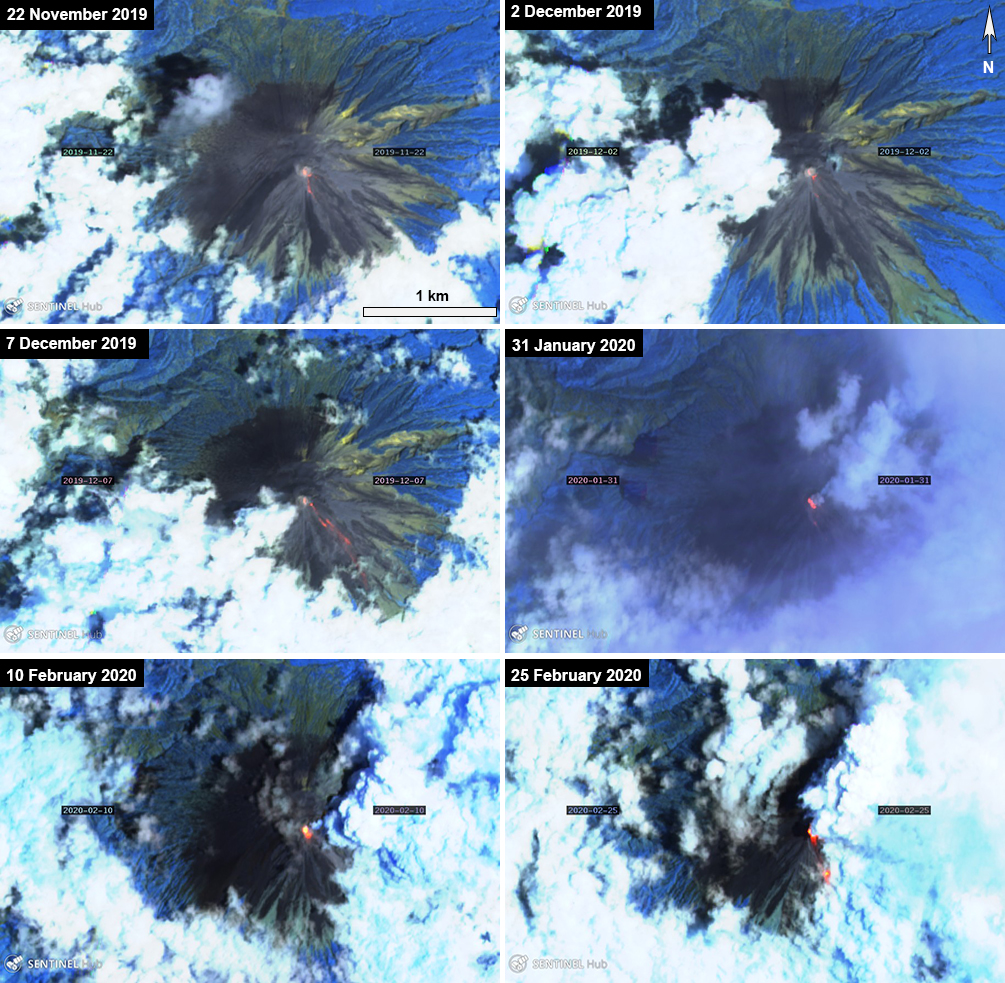

Ash plumes and thermal anomalies continue during September 2019-February 2020

Semisopochnoi (United States)

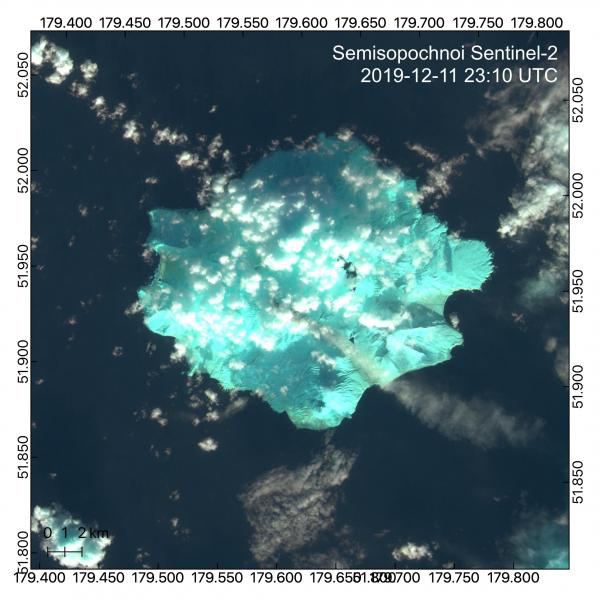

Intermittent small explosions detected in December 2019 through mid-March 2020

Stromboli (Italy)

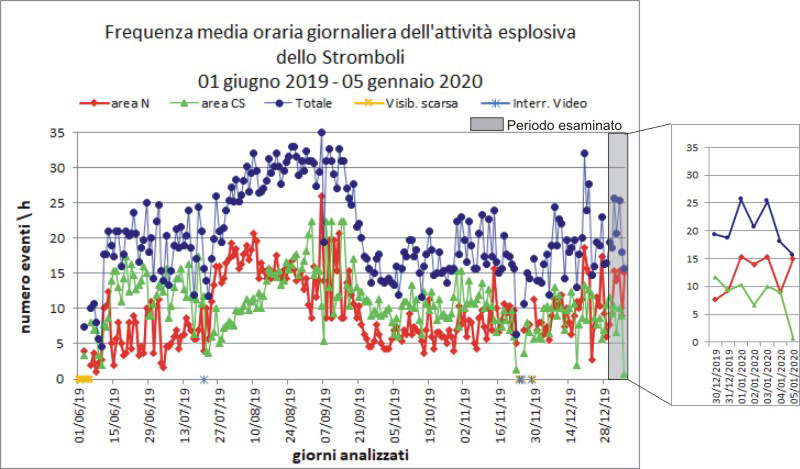

Strombolian activity continues at both summit crater areas, September-December 2019

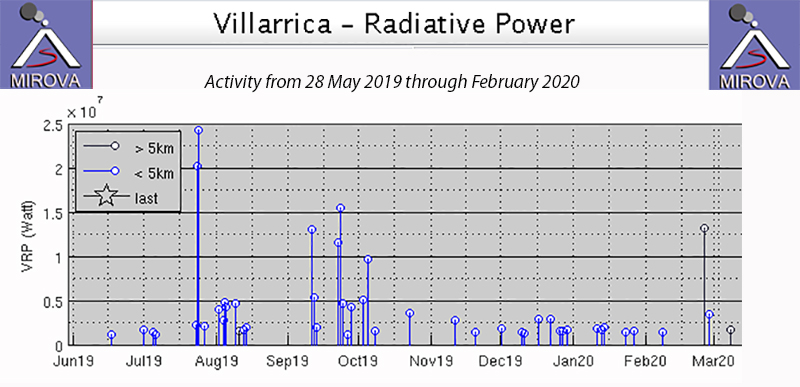

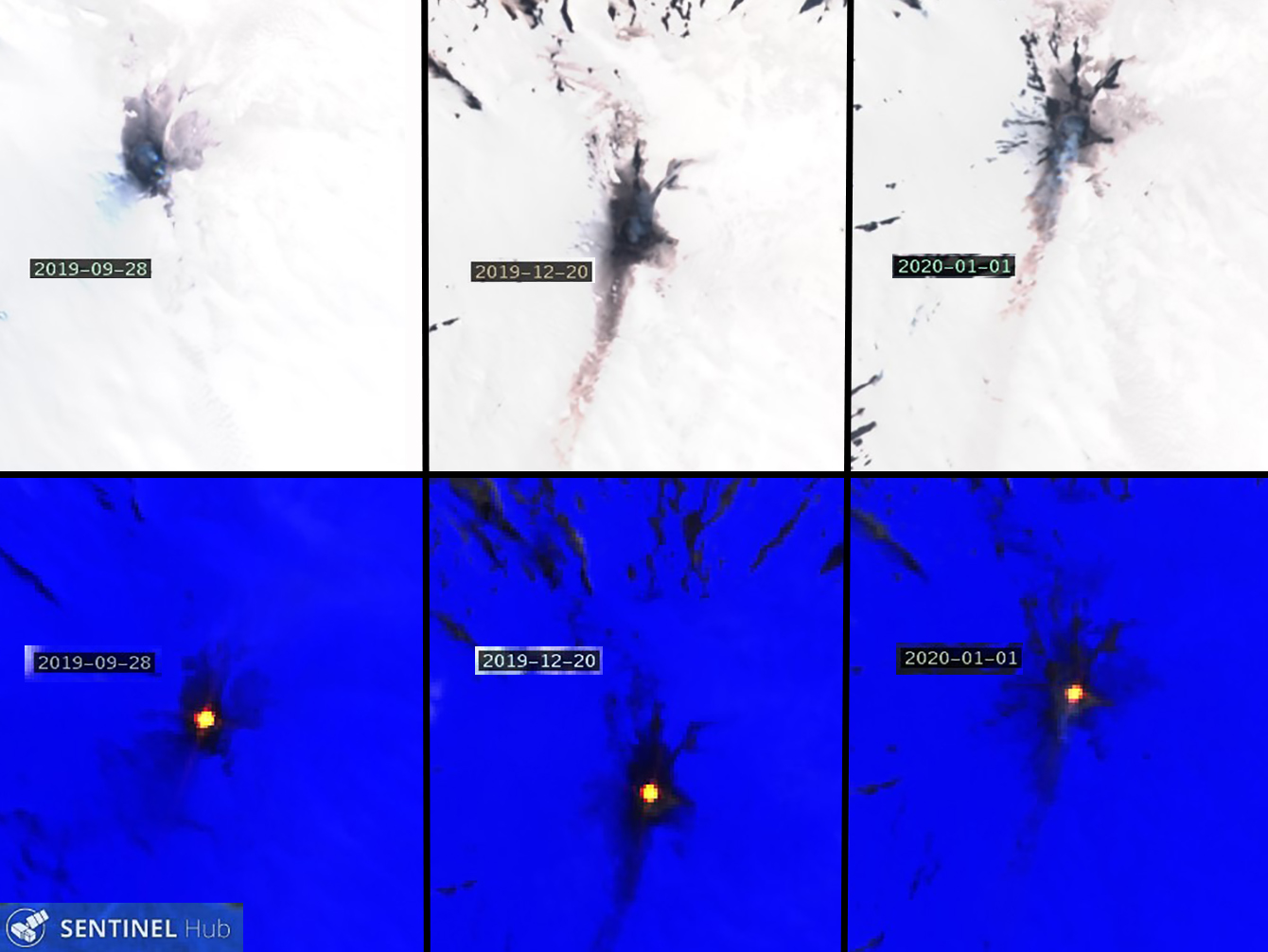

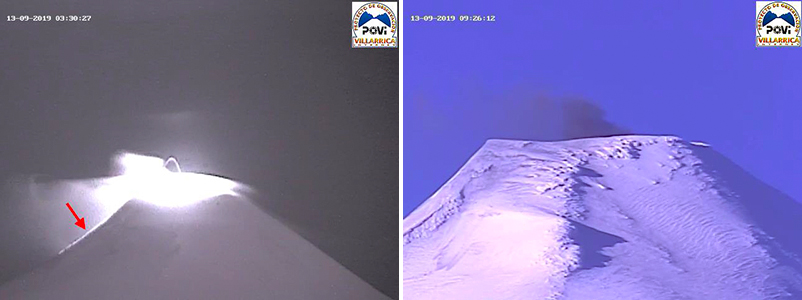

Villarrica (Chile)

Brief increase in explosions, mid-September 2019; continued thermal activity through February 2020

Etna

Italy

37.748°N, 14.999°E; summit elev. 3357 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Strombolian explosions and ash emissions continue, October 2019-March 2020

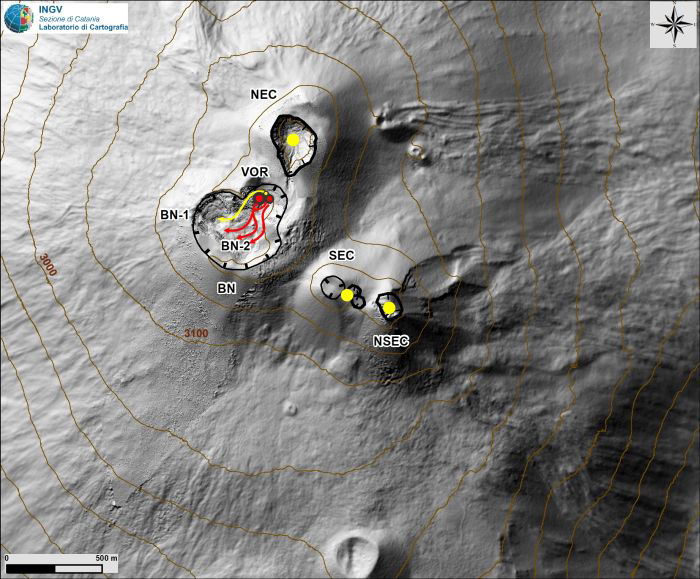

Mount Etna is a stratovolcano located on the island of Sicily, Italy, with historical eruptions that date back 3,500 years. The most recent eruptive period began in September 2013 and has continued through March 2020. Activity is characterized by Strombolian explosions, lava flows, and ash plumes that commonly occur from the summit area, including the Northeast Crater (NEC), the Voragine-Bocca Nuova (or Central) complex (VOR-BN), the Southeast Crater (SEC, formed in 1978), and the New Southeast Crater (NSEC, formed in 2011). The newest crater, referred to as the "cono della sella" (saddle cone), emerged during early 2017 in the area between SEC and NSEC. This reporting period covers information from October 2019 through March 2020 and includes frequent explosions and ash plumes. The primary source of information comes from the Osservatorio Etneo (OE), part of the Catania Branch of Italy's Istituo Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologica (INGV).

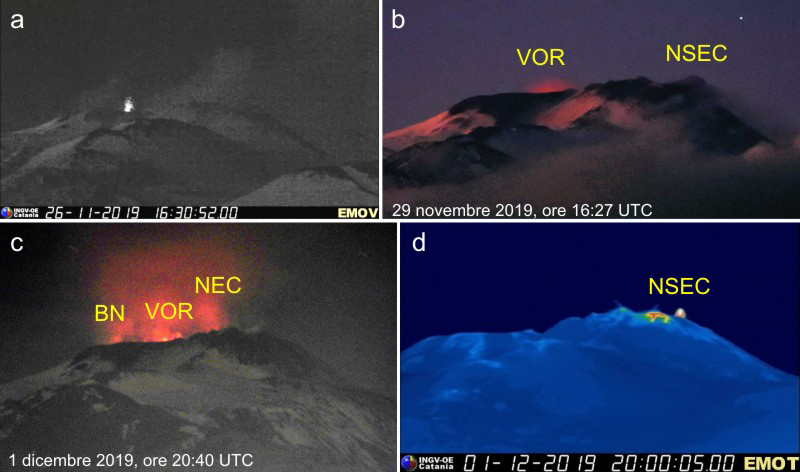

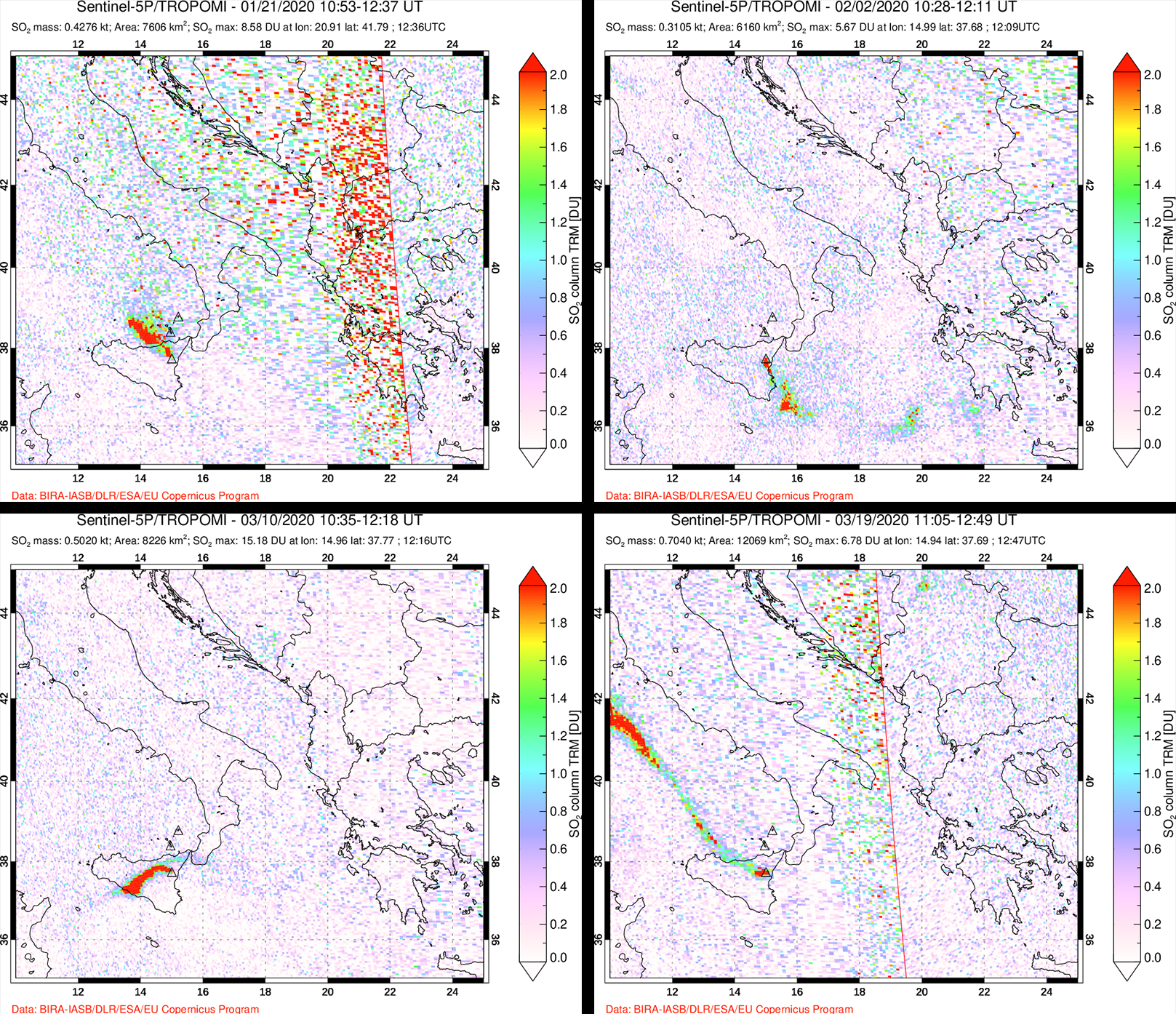

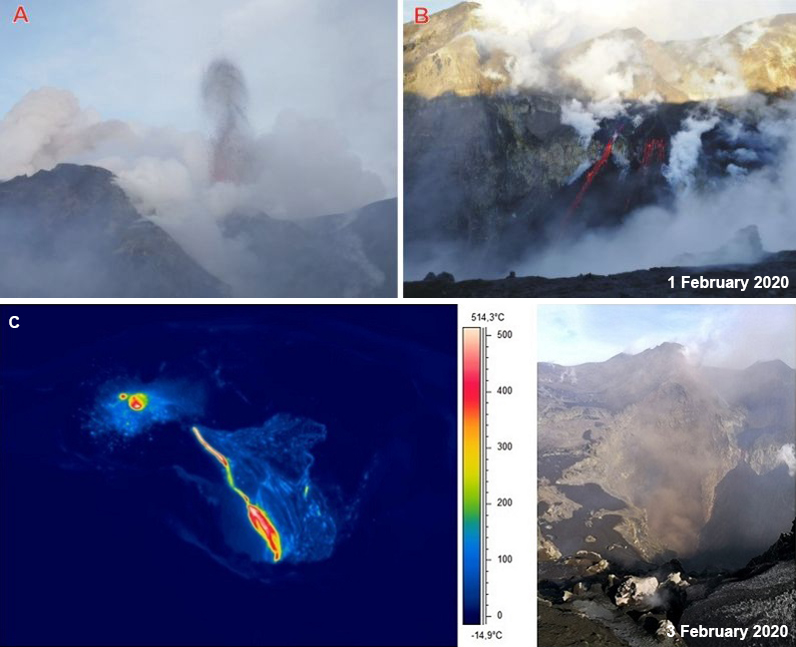

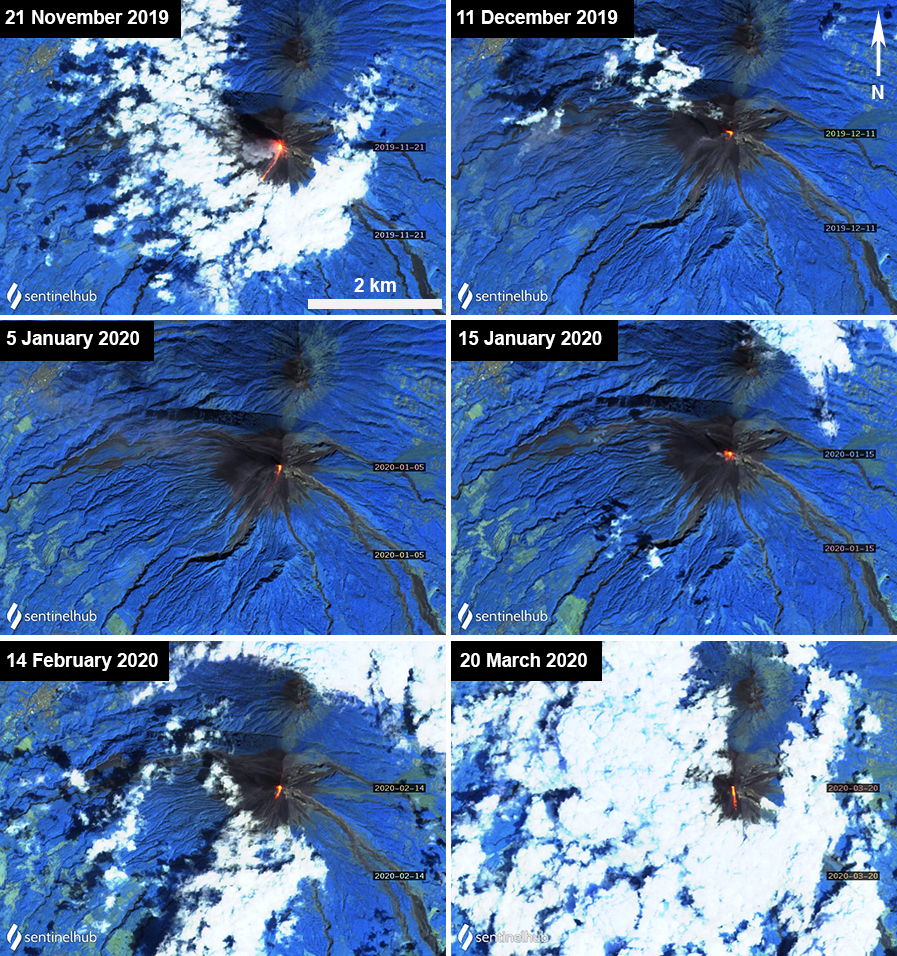

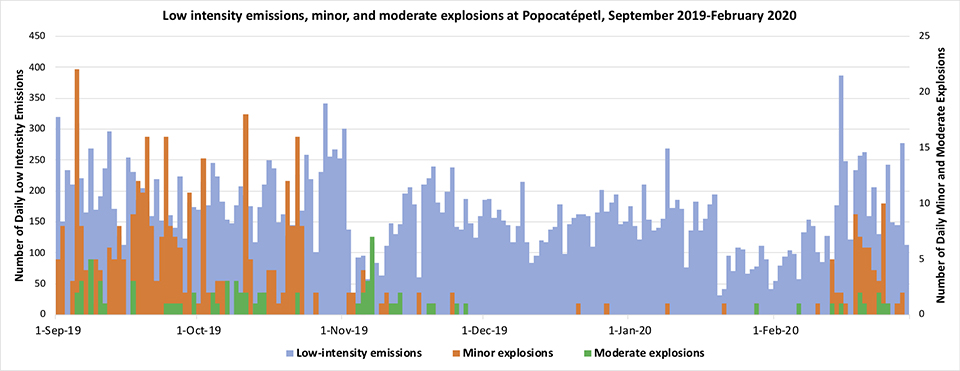

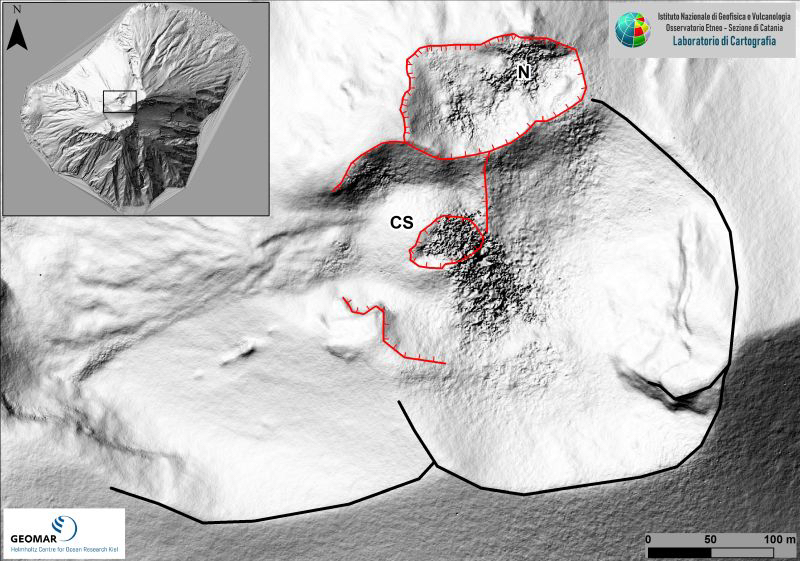

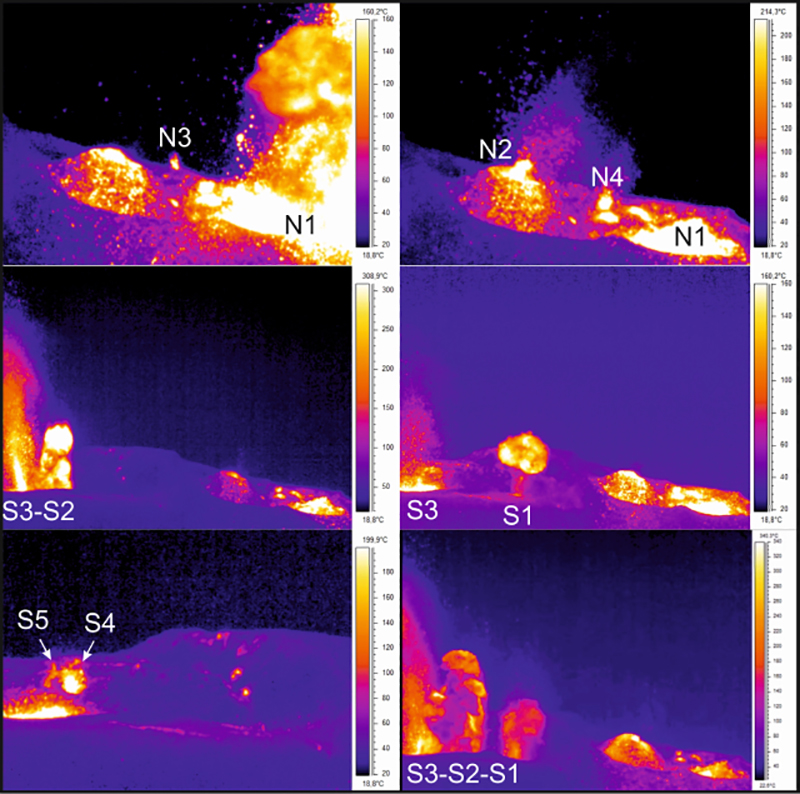

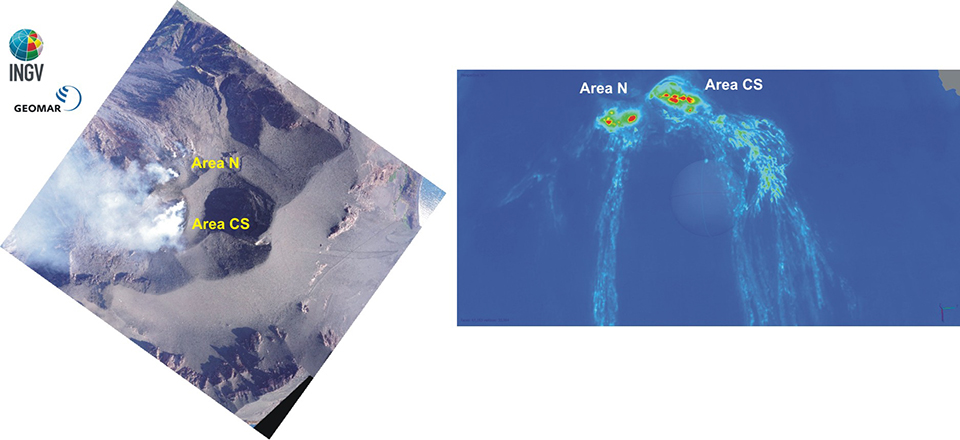

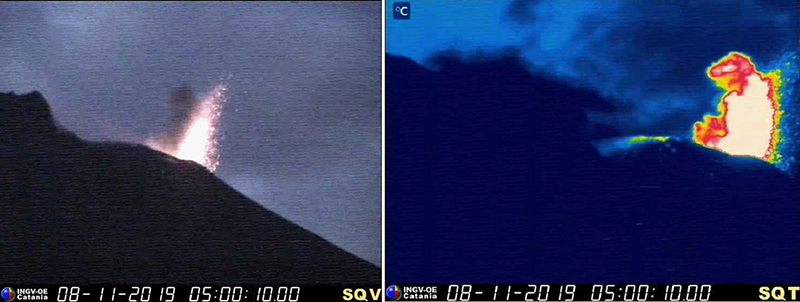

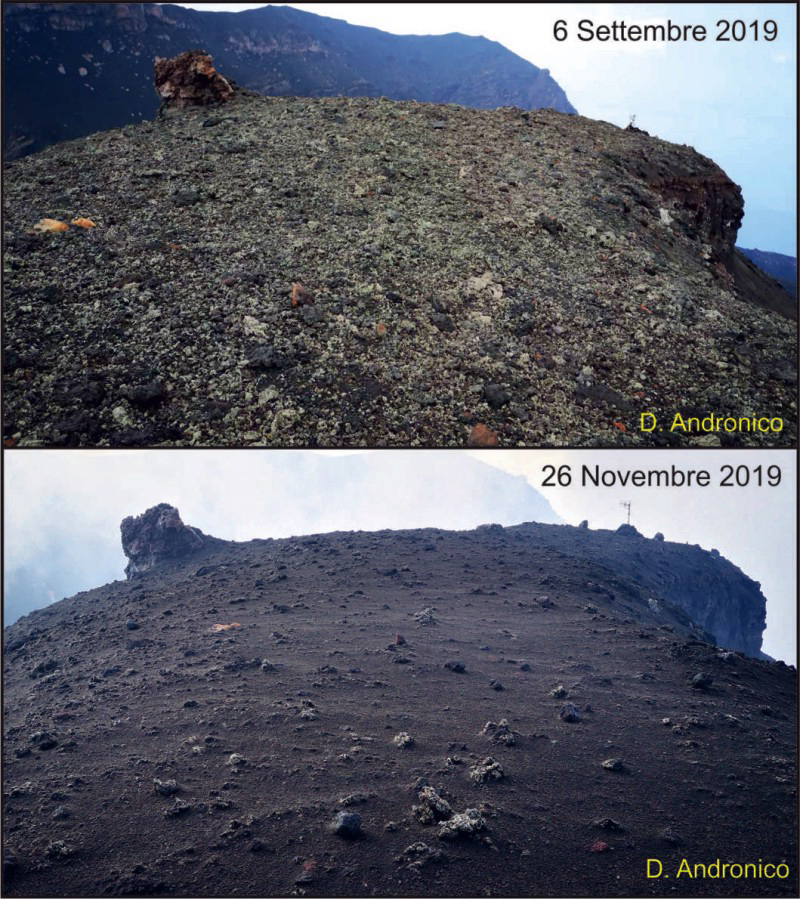

Summary of activity during October 2019-March 2020. Strombolian activity and gas-and-steam and ash emissions were frequently observed at Etna throughout the entire reporting period, according to INGV and Toulouse VAAC notices. Activity was largely located within the main cone (Voragine-Bocca Nuova complex), the Northeast Crater (NEC), and the New Southeast Crater (NSEC). On 1, 17, and 19 October, ash plumes rose to a maximum altitude of 5 km. Due to constant Strombolian explosions, ground observations showed that a scoria cone located on the floor of the VOR Crater had begun to grow in late November and again in late January 2020. A lava flow was first detected on 6 December at the base of the scoria cone in the VOR Crater, which traveled toward the adjacent BN Crater. Additional lava flows were observed intermittently throughout the reporting period in the same crater. On 13 March, another small scoria cone had formed in the main VOR-BN complex due to Strombolian explosions.

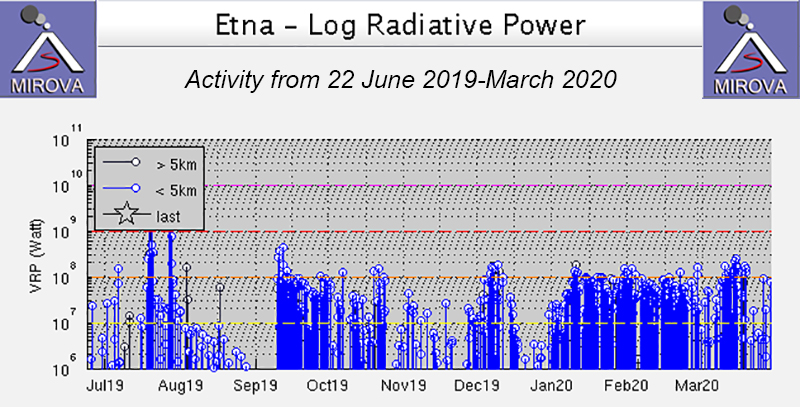

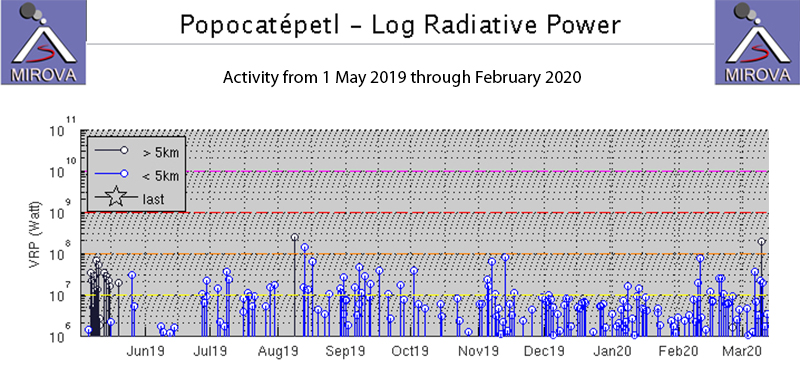

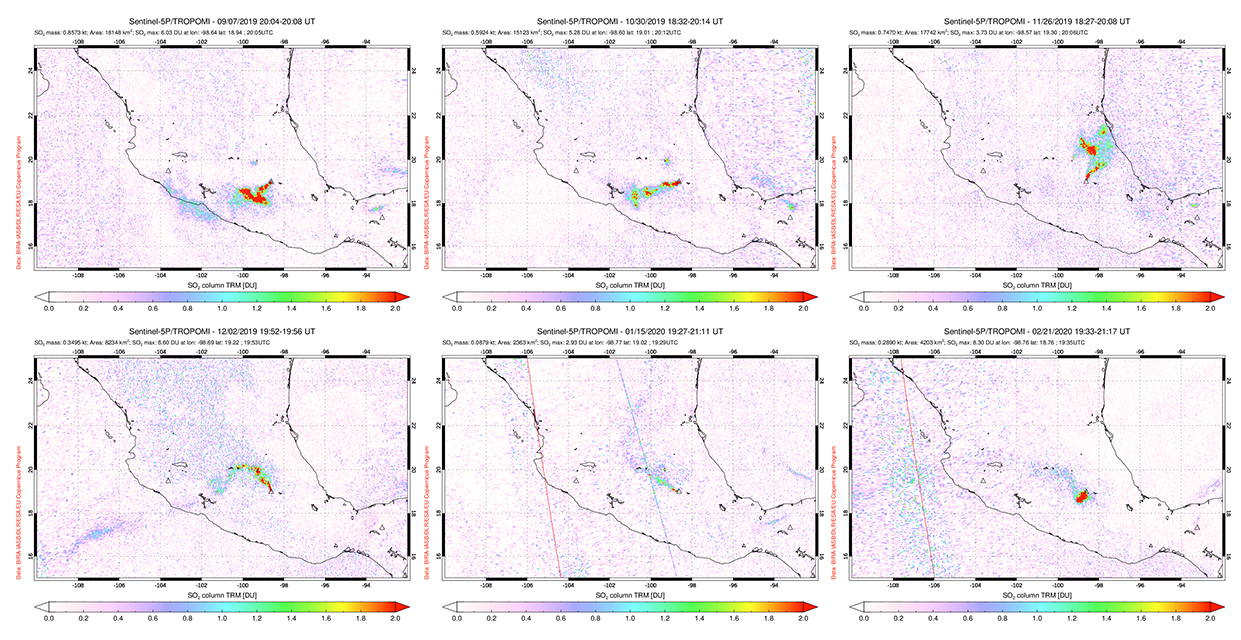

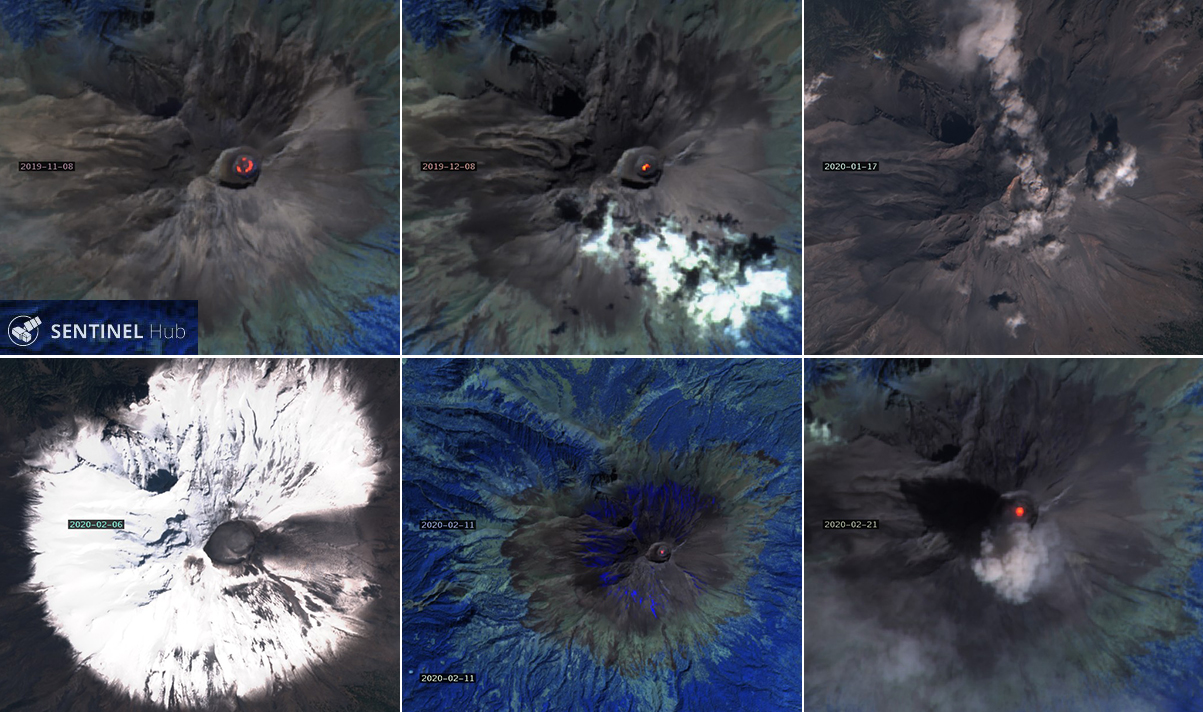

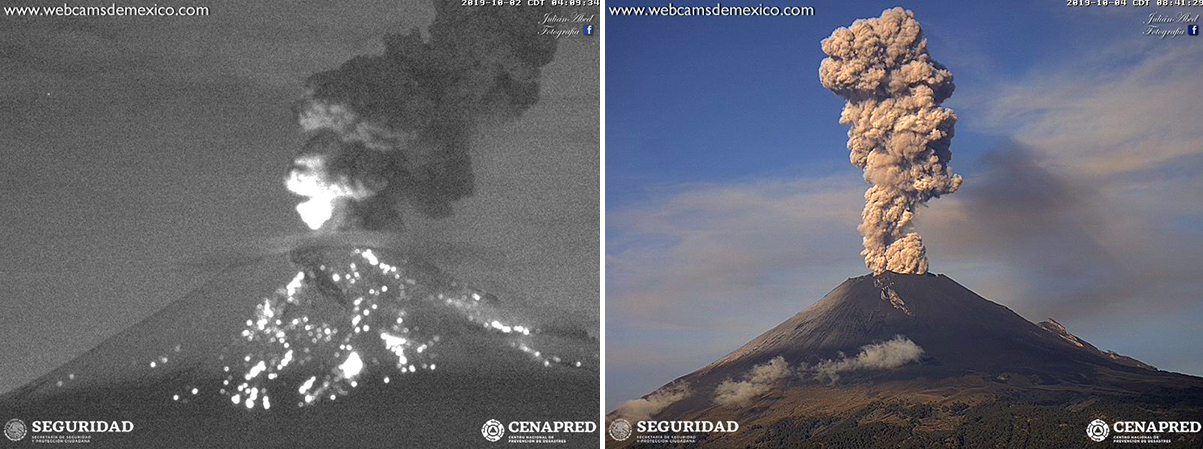

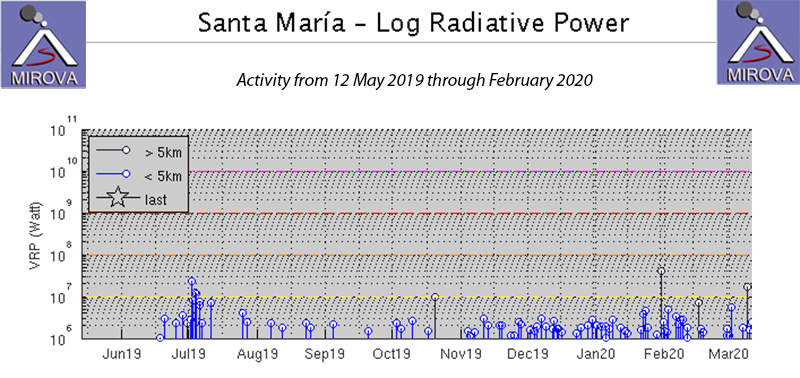

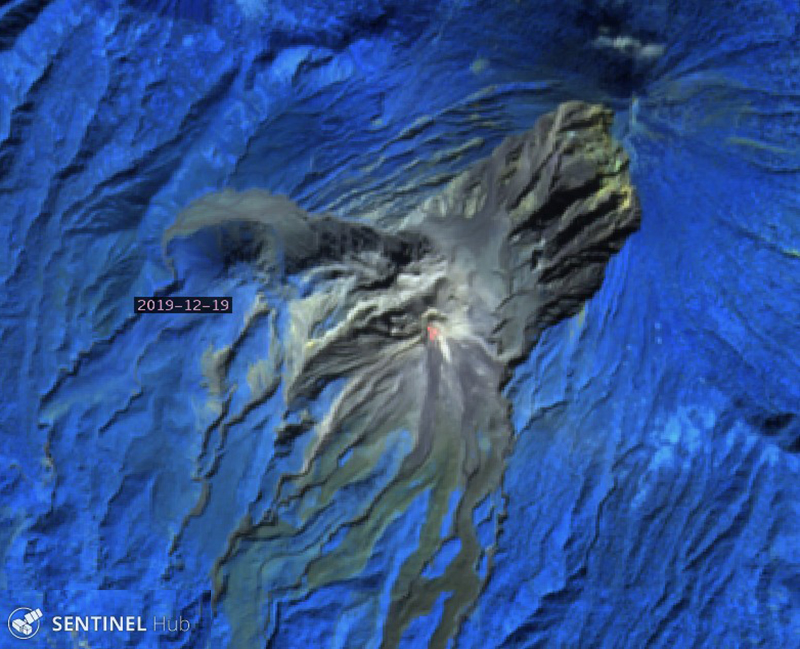

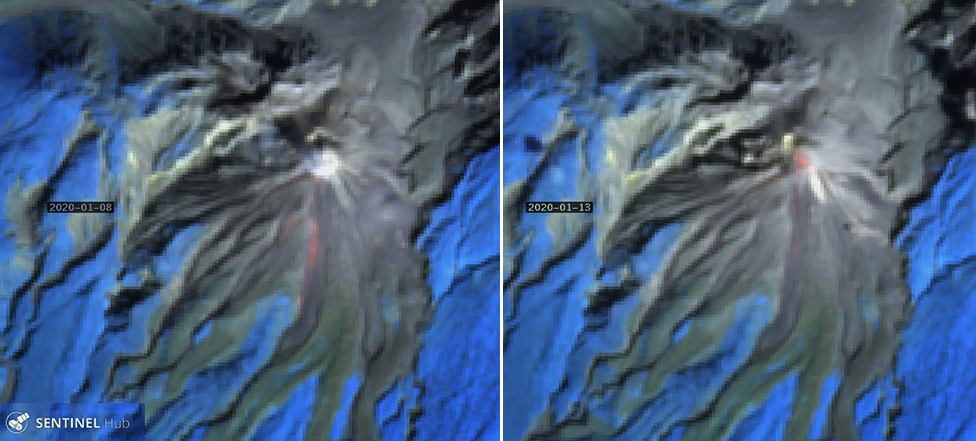

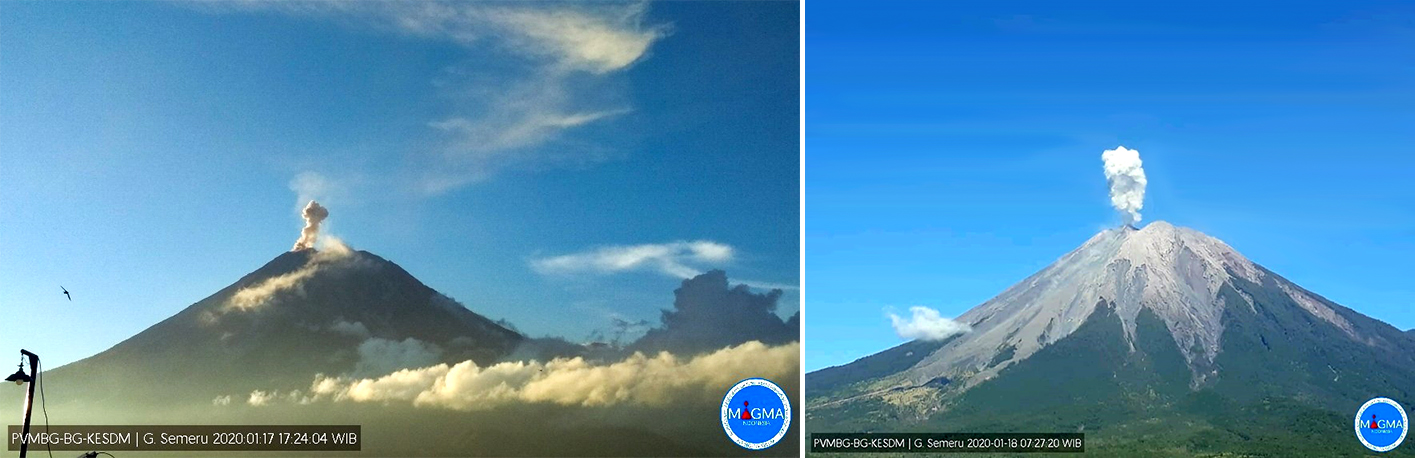

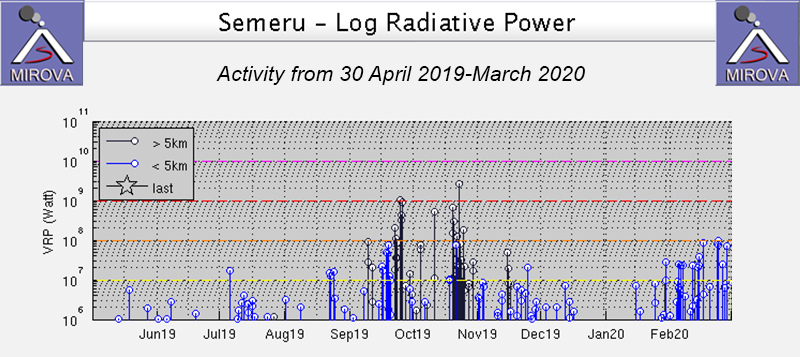

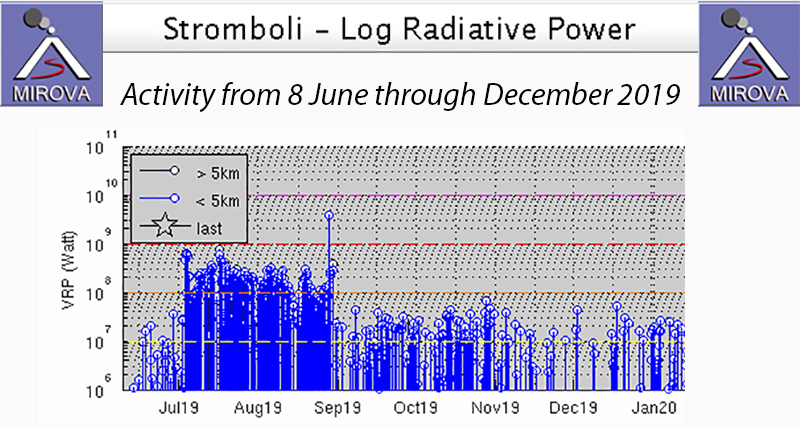

MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) analysis of MODIS satellite data shows multiple episodes of thermal activity varying in power from 22 June 2019 to March 2020 (figure 286). The power and frequency of these thermal anomalies significantly decreased between August to mid-September. The pulse of activity in mid-September reflected a lava flow from the VOR Crater (BGVN 44:10). By late October through November, thermal anomalies were relatively weaker and less frequent. The next pulse in thermal activity reflected in the MIROVA graph occurred in early December, followed by another shortly after in early January, both of which were due to new lava flows from the VOR Crater. After 9 January the thermal anomalies remained frequent and strong; active lava flows continued through March accompanied by Strombolian explosions, gas-and-steam, SO2, and ash emissions. The most recent distinct pulse in thermal activity was seen in mid-March; on 13 March, another lava flow formed, accompanied by an increase in seismicity. This lava flow, like the previous ones, also originated in the VOR Crater and traveled W toward the BN Crater.

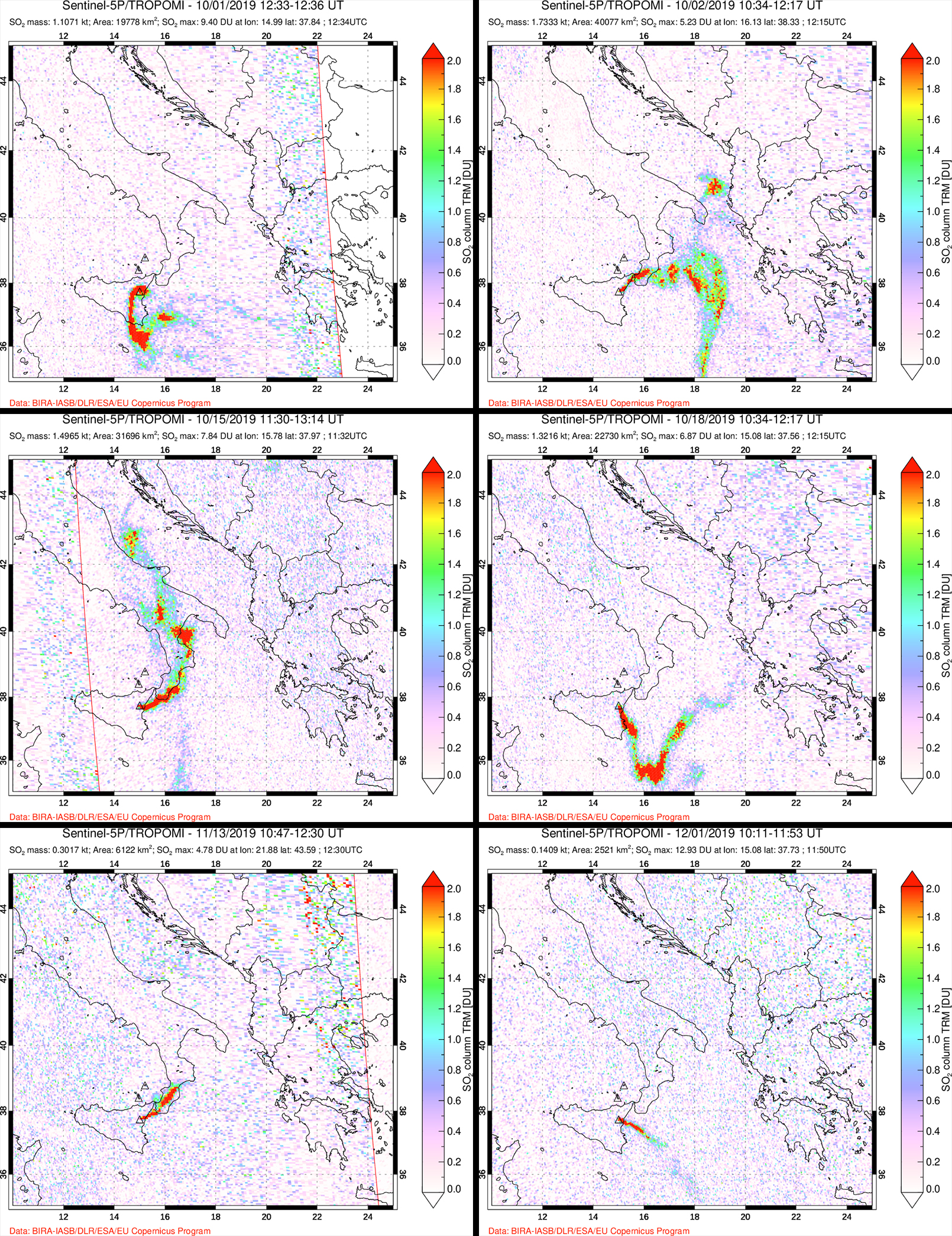

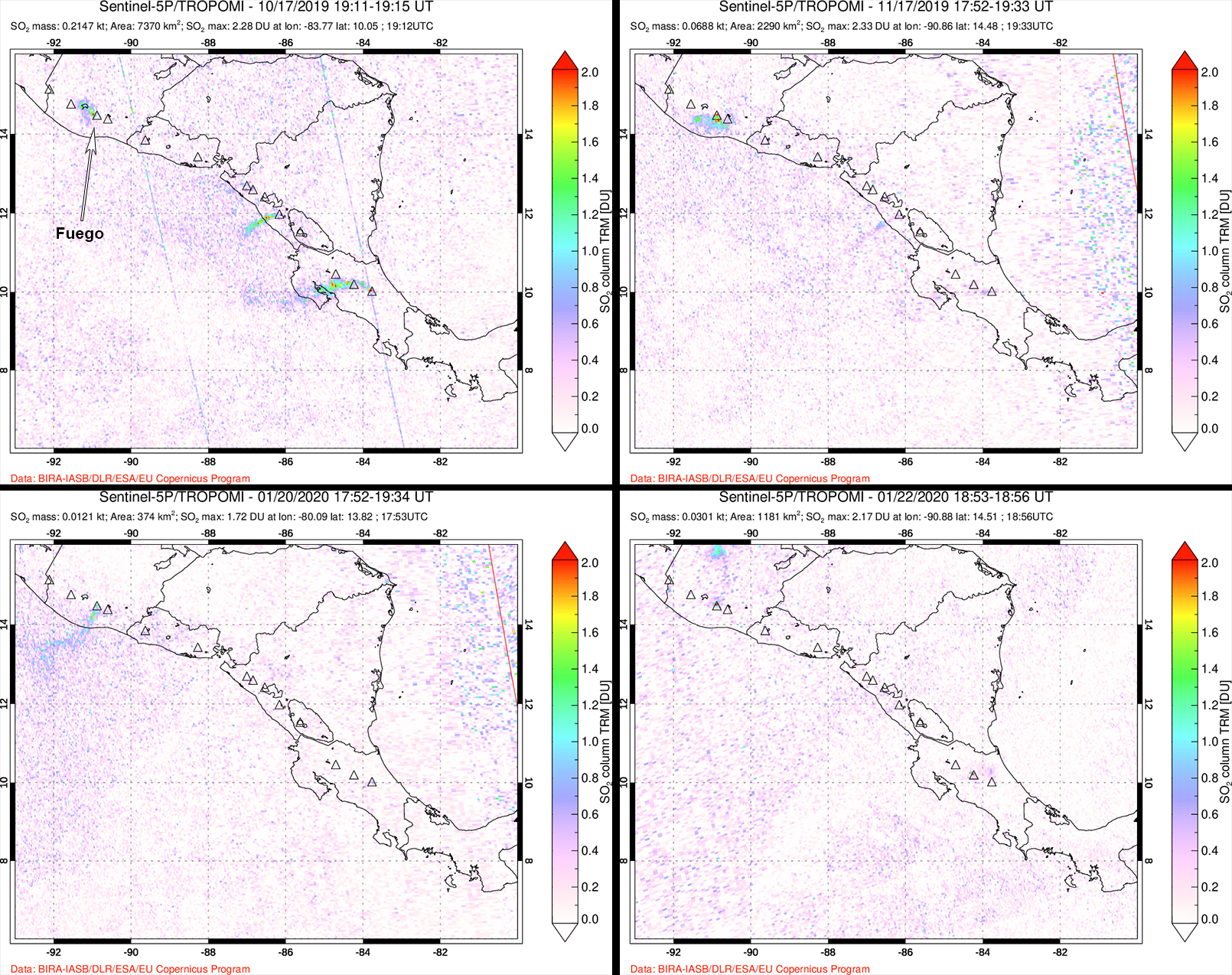

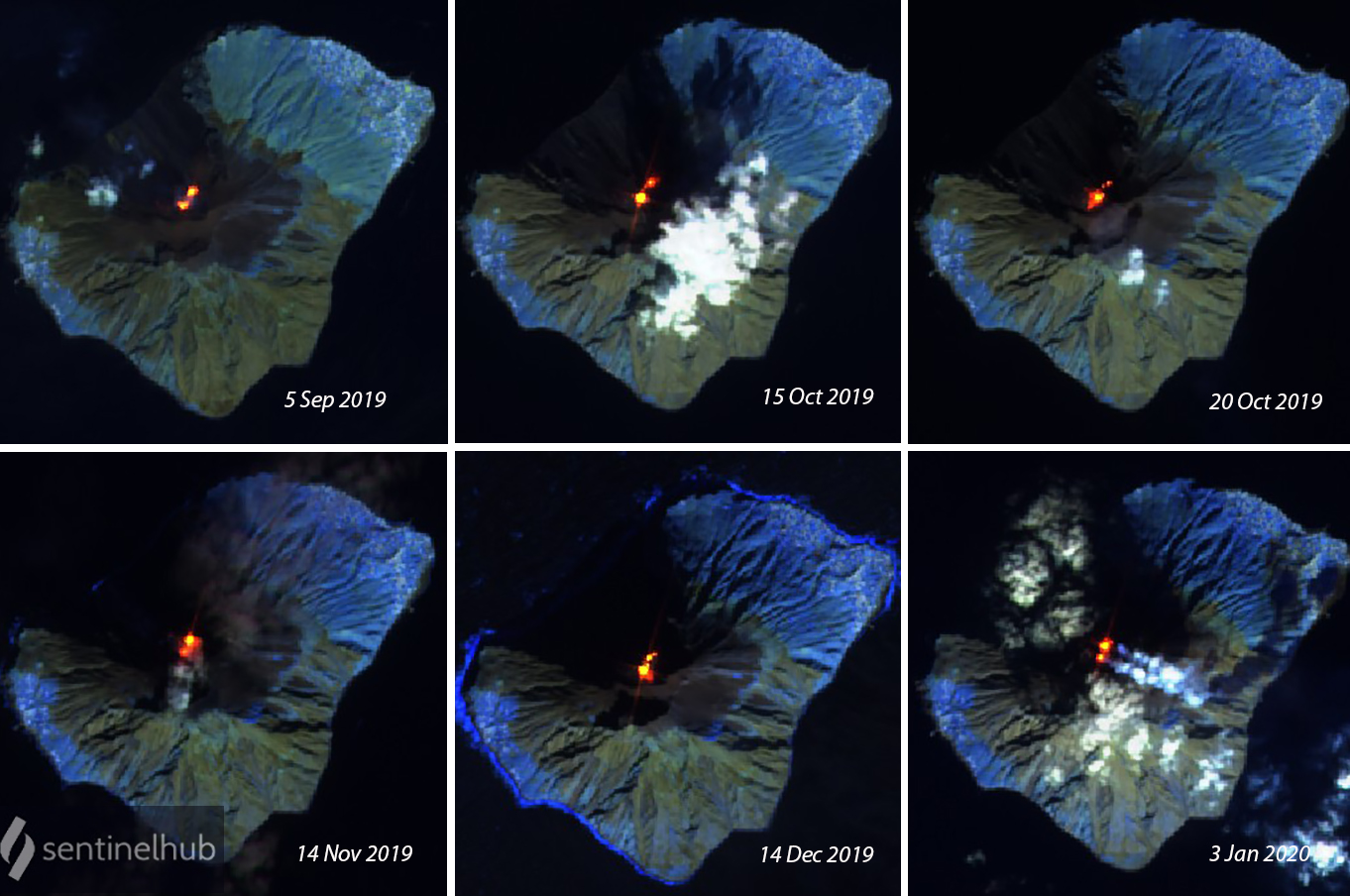

Activity during October-December 2019. During October 2019, VONA (Volcano Observatory Notice for Aviation) notices issued by INGV reported ash plumes rose to a maximum altitude of 5 km on 1, 17, and 19 October. Strombolian explosions occurred frequently. Explosions were detected primarily in the VOR-BN Craters, ejecting coarse pyroclastic material that fell back into the crater area and occasionally rising above the crater rim. Ash emissions rose from the VOR-BN and NEC while intense gas-and-steam emissions were observed in the NSEC (figure 287). Between 10-12 and 14-20 October fine ashfall was observed in Pedara, Mascalucia, Nicolosi, San Giovanni La Punta, and Catania. In addition to these ash emissions, the explosive Strombolian activity contributed to significant SO2 plumes that drifted in different directions (figure 288).