Report on Long Valley (United States) — April 1996

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 21, no. 4 (April 1996)

Managing Editor: Richard Wunderman.

Long Valley (United States) Summary of 1995 activity; March-April 1996 earthquake swarm

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 1996. Report on Long Valley (United States) (Wunderman, R., ed.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 21:4. Smithsonian Institution. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.BGVN199604-323822

Long Valley

United States

37.7°N, 118.87°W; summit elev. 3390 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

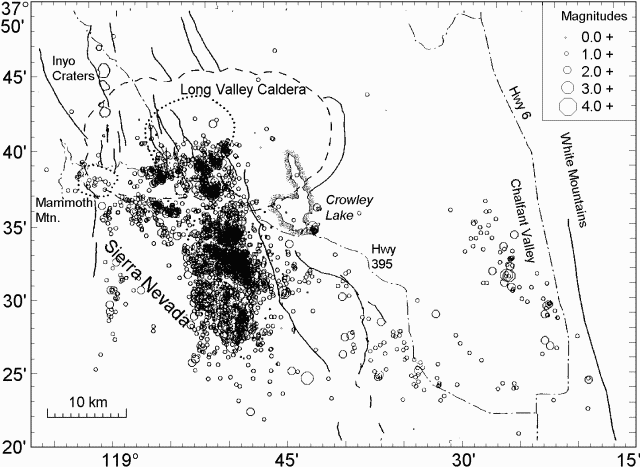

The 17 x 32 km Long Valley caldera (figure 18) lies E of the central Sierra Nevada, ~320 km E of San Francisco. The caldera formed about 730,000 years ago as a result of the Bishop Tuff eruption. Resurgent doming was followed by eruptions of rhyolite from the caldera moat and rhyodacite from the outer ring-fracture vents until ~50,000 years ago. Since then the caldera has remained thermally active, and in recent years has undergone significant deformation. Although distinct from Long Valley Caldera, both Inyo Craters and Mammoth Mountain sit adjacent to it. The following report summarizes a more detailed report on caldera seismicity, deformation, and CO2 discharge at Mammoth Mountain during 1995 (Hill, 1996).

Two earthquakes on 2 and 4 January 1995 (M 3.2 and 2.5, respectively), occurred in the area just W of the Highway 203-395 junction. After these events, the epicentral area, a locality with frequent earthquake swarms, turned relatively quiet for the remainder of 1995. Then, after a M 3.3 earthquake on 14 January centered in the S moat, the activity in the caldera shifted to the E. Seismicity through the rest of 1995 in the caldera and adjacent areas was largely confined to a N-S corridor extending from the SE margin of the resurgent dome to the wall of the caldera and beyond into the Sierra Nevada block (figure 18).

On 4 March, M 4.4 and 4.3 earthquakes occurred near the southern caldera boundary: these were the largest events to occur in the region during 1995. A swarm on 19-20 March in the S moat included more than 150 M > 1 earthquakes and three M > 3 events. Activity slowed down through mid-June both within the caldera and in the Sierra Nevada block. Activity within the caldera picked up briefly on 23 and 27 June, with swarms at the S margin of the resurgent dome. Each included a M > 3 earthquake accompanied by more than 20 smaller events.

Beginning with the last two days of June, activity shifted S to the Sierra Nevada block. A brief pause near the end of July was followed by a stronger surge in the number of earthquakes through August and September. This swarm-like surge included more than 20 M > 3 earthquakes with individual clusters, commonly producing 20-30 events. The largest cluster occurred on 17 September and included a M 3.7 earthquake and over 50 smaller events. Seismic activity also increased along the SW stretch of the caldera and at the S outlet of Crowley lake, where earthquakes clustered at a depth of 10 km. Both areas previously had low seismicity. After September seismicity gradually slowed through the end of the year.

Mammoth Mountain continued to produce small (M <2) earthquakes in the upper 10 km of the crust whereas long-period events took place at depths of 10-30 km beneath the SW flank. These long-period earthquakes continued at the steady rate of 20-25 events/year; their epicenters were distributed along a belt extending S of Mammoth Mountain well into the Sierra Nevada block.

The resurgent dome continued to inflate at a strain rate of 2-3 ppm/year, a value that corresponds to an uplift rate of 2-3 cm/year based on past comparisons with results from leveling data. This rate may be gradually slowing with time, as suggested by a number of geodimeter baselines. In mid-1995, most baselines showed a brief pause in extension followed by a period of increased extension rate. The timing of this pause with respect to the onset of the seismicity surge in the Sierra Nevada to the S is intriguing. Similar, but less pronounced variations in extension rate occurred at fairly regular intervals since 1991 (BGVN 19:04 and 20:03). No systematic relation to seismicity variations either within the caldera or the Sierra Nevada block were ever recorded.

The areas of dead pine trees on the flanks of Mammoth Mountain expanded during 1995 and new areas formed in the vicinity of Reds Creek on the W flank and on the N flank above the main ski lodge. In all of these areas, high concentrations of CO2 and small amounts of helium were measured. In general the soil-gas He/CO2 ratio was similar to that in the fumarole just S of the Chair 3 lift on the E flank.

Earthquake swarm, March-April 1996. A M 3.9 earthquake on 29 March 1996 triggered an earthquake swarm in the S moat of Long Valley crater. By 2 April more than 1,000 aftershocks (M > 0.5) were detected and located; 18 of these events had M > 3, and the two largest events reached M 4. The highest rate, up to 40 events/hour, was recorded during the night of 30-31 March. The decline in activity was accompanied by four M > 3.3 earthquakes during the rest of 31 March. Epicenters were clustered 10-11 km ESE of Mammoth Lakes at depths of 7-11 km. No ground deformation was associated with this swarm.

References. Hill, David P., 1996, Long Valley Caldera Monitoring Report (October-December 1995): U.S. Geological Survey, Office of Earthquakes, Volcanoes, and Engineering, 31 p.

Geological Summary. The large 17 x 32 km Long Valley caldera east of the central Sierra Nevada Range formed as a result of the voluminous Bishop Tuff eruption about 760,000 years ago. Resurgent doming in the central part of the caldera occurred shortly afterwards, followed by rhyolitic eruptions from the caldera moat and the eruption of rhyodacite from outer ring fracture vents, ending about 50,000 years ago. During early resurgent doming the caldera was filled with a large lake that left strandlines on the caldera walls and the resurgent dome island; the lake eventually drained through the Owens River Gorge. The caldera remains thermally active, with many hot springs and fumaroles, and has had significant deformation, seismicity, and other unrest in recent years. The late-Pleistocene to Holocene Inyo Craters cut the NW topographic rim of the caldera, and along with Mammoth Mountain on the SW topographic rim, are west of the structural caldera and are chemically and tectonically distinct from the Long Valley magmatic system.

Information Contacts: David Hill, U.S. Geological Survey, MS 977, 345 Middlefield Road, Menlo Park, CA 94025 (URL: https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/observatories/calvo/).