Report on Galeras (Colombia) — March 1991

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 16, no. 3 (March 1991)

Managing Editor: Lindsay McClelland.

Galeras (Colombia) Frequent ash emissions; slight inflation

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 1991. Report on Galeras (Colombia) (McClelland, L., ed.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 16:3. Smithsonian Institution. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.BGVN199103-351080

Galeras

Colombia

1.22°N, 77.37°W; summit elev. 4276 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Ash emissions, accompanied by tremor episodes and long-period earthquakes, were frequent in March. Occasional lapilli accumulations were noted around the vents. Incandescence continued to be visible on the inner W wall of the crater, and the Portillas fumarole increased notably in diameter. Fissures and loose material made the crater wall appear gravitationally unstable. Outside of the crater, Besolima fissure fumarole temperatures declined from 538°C in February to 514°C in March; temperatures of 738°C were recorded in September, shortly after the fissure opened. The SO2 flux, measured by COSPEC, ranged from 450 to 1,647 t/d during the first week of March.

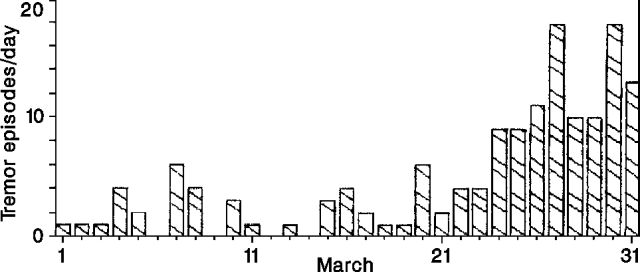

The number of long period earthquakes ranged between 30 and 90/day, while high-frequency seismicity decreased in March. At the end of March, a large increase in the number of tremor episodes was recorded (figure 35). Inflation continued to be recorded 0.9 km E of the main crater (at the "Crater" electronic tiltmeter), totalling 70 µrad since September.

Geological Summary. Galeras, a stratovolcano with a large breached caldera located immediately west of the city of Pasto, is one of Colombia's most frequently active volcanoes. The dominantly andesitic complex has been active for more than 1 million years, and two major caldera collapse eruptions took place during the late Pleistocene. Long-term extensive hydrothermal alteration has contributed to large-scale edifice collapse on at least three occasions, producing debris avalanches that swept to the west and left a large open caldera inside which the modern cone has been constructed. Major explosive eruptions since the mid-Holocene have produced widespread tephra deposits and pyroclastic flows that swept all but the southern flanks. A central cone slightly lower than the caldera rim has been the site of numerous small-to-moderate eruptions since the time of the Spanish conquistadors.

Information Contacts: INGEOMINAS-OVP.