Report on Lascar (Chile) — March 1994

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 19, no. 3 (March 1994)

Managing Editor: Richard Wunderman.

Lascar (Chile) Dome collapse almost complete; new fractures and fumaroles; small ash emissions

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 1994. Report on Lascar (Chile) (Wunderman, R., ed.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 19:3. Smithsonian Institution. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.BGVN199403-355100

Lascar

Chile

23.37°S, 67.73°W; summit elev. 5592 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Normal fumarolic activity has continued since the small eruption on 17 December 1993. During fieldwork between 10 February and 5 March, the plume was unusually low (200-400 m above the crater), with occasional increases to normal levels (800-1,000 m). The yellowish plume sometimes contained small amounts of gray ash. A short-lived eruption on the [evening] of 27 February was witnessed by S. Matthews from 40 km W of the volcano. A high dark eruption column produced a plume extending W and WNW; the plume detached from the volcano 15 minutes later. On 28 February the Argentinian Civil Defense reported that ash had fallen in Jujuy, Argentina (~265 km SE). Fumarolic activity diminished the next day.

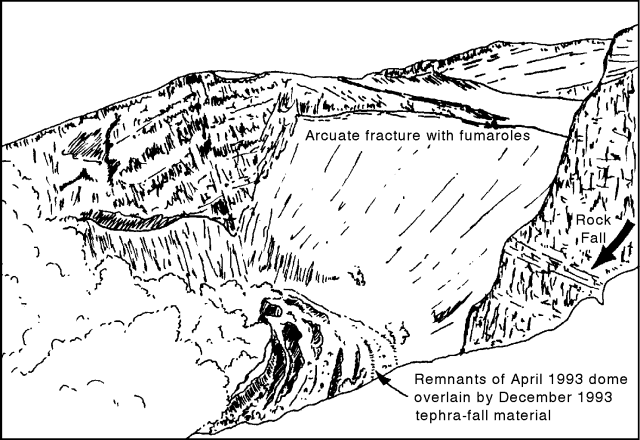

Crater observations, 19 February 1994. Gardeweg and Matthews reached the summit using a helicopter provided by the Fuerza Aerea de Chile. The April 1993 dome (18:4) had been almost completely replaced by a deep hole (bottom not visible) produced by continuous collapse into the vent (18:11). It occupied the central and N side of the previously flat surface of the dome. The S side of the dome was cut by deep annular collapse fractures (figure 20). Strong degassing was concentrated in the collapse crater. Weaker fumarolic activity was observed along the outer fractures and margin of the dome. These had persistent low-velocity emissions without the "jet engine" noise heard on previous visits. Yellow sulfur deposits associated with small fumaroles were also observed on the inner crater walls. Continuous rockfall into the active crater was observed coming from the overhanging W wall and the higher part of the S wall.

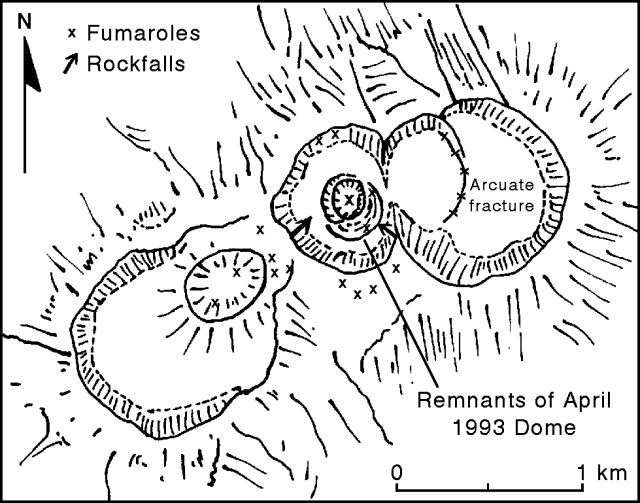

New fractures and fumaroles defined an elliptical zone centered on the active crater, but incorporating a larger part of the edifice (figure 21). An annular fracture with active fumaroles was observed along the rim of a previously inactive crater to the E. Small fumaroles were also present on the inside of the N wall and up to 50 m outside the S wall of the active crater. Two types of fumaroles occurred on the E side of the older W edifice, aligned on small (2, and H2SO4, and precipitating yellow and white sulfate minerals. The second type were hot (>=230°C) active fumaroles emitting steam and SO2, and depositing white sulfur.

|

Figure 21. Sketch of the summit area of Lascar, with its five nested craters, on 19 February 1994. New fumarole fields and unstable sites with continuous rockfall are shown. Diagram by S. Matthews. |

Potential hazards. Subsidence of the crater floor as a result of conduit degassing since April 1993 has destabilized the inner part of the entire edifice. Collapse of the central part of the dome began in May 1993, coincident with the first observation of fumaroles on the S side of the active crater. An aerial photograph taken on 26 April 1993 shows a distinct fumarole on the inside rim of the N wall. Part of the subsidence occurred during the December 1993 eruption, as shown by aerial photographs taken by the Chilean Air Force on 28 December. As of early March, the apparent blockage of the degassing system due to dome collapse was similar to pre-eruptive conditions observed in previous cycles, and is likely to cause another eruption in the near future. If subsidence and widening of the collapse zone continues, the entire edifice may be destabilized. Another potential hazard involves slippage of the overhanging W wall of the active crater, which may also block the degassing system leading to "throat clearing" eruptions.

Additional information about past activity. Photographs taken on the morning of 17 December 1993 by Gonzalo Cabero (MINSAL) from Toconao (35 km NW) show a vertical column rising 8,000-9,000 m above the rim of the active crater. A small umbrella developed in the upper third of the column, but no plume extended laterally from the volcano. Partial column collapse generated weak ash clouds to the N and S, but no new pyroclastic deposits were recognized during fieldwork. No bomb ejections or ashfall were reported from this activity. However, fieldwork between 10 February and 5 March identified a large number of bombs within 3.5 km of the crater that had been erupted after April 1993. Blocks from the April 1993 eruption (18:4) exhibited a wide variety of density and textures. The more recent blocks are distinctly different, composed of dense, banded glassy andesite.

A previously unreported eruption, on an unknown day in August 1993, was observed from Soncor (~15 km W). A black ash cloud rose 1-2 km above the crater in ~ 10 minutes; no sound or seismicity was detected. This small eruption was probably a result of dome collapse.

Gregg Bluth provided the following satellite-based TOMS results for the 19 April 1993 eruption. Tonnage calculations did not require reflectivity corrections, but the scan bias was accounted for. An SO2 cloud was not visible on 19 April, but one was observed on 20-22 April. The SO2 cloud on 20 April was streaming from the volcano to ~1,800 km E and SE; tonnage was 355 kt. By 21 April the SO2 cloud had separated from the volcano by ~300 km and continued drifting SE. The leading edge was ~2,000 km SE of the volcano. The measured SO2 on this day was 340 kt. By 22 April some values were still above background, but there was no obvious cloud mass. On 23 April only a few pixels were above background; no days were checked after 23 April. The elongated cloud seen on 20 April indicates that earlier SO2 emissions may have been lost to TOMS observation. However, because the SO2 cloud showed only a slight decrease the next day, there is no justification for estimating a significantly higher original emission based on an SO2 loss rate. Estimated total SO2 yield for this eruption was 400 kt.

Geological Summary. Láscar is the most active volcano of the northern Chilean Andes. The andesitic-to-dacitic stratovolcano contains six overlapping summit craters. Prominent lava flows descend its NW flanks. An older, higher stratovolcano 5 km E, Volcán Aguas Calientes, displays a well-developed summit crater and a probable Holocene lava flow near its summit (de Silva and Francis, 1991). Láscar consists of two major edifices; activity began at the eastern volcano and then shifted to the western cone. The largest eruption took place about 26,500 years ago, and following the eruption of the Tumbres scoria flow about 9000 years ago, activity shifted back to the eastern edifice, where three overlapping craters were formed. Frequent small-to-moderate explosive eruptions have been recorded since the mid-19th century, along with periodic larger eruptions that produced ashfall hundreds of kilometers away. The largest historical eruption took place in 1993, producing pyroclastic flows to 8.5 km NW of the summit and ashfall in Buenos Aires.

Information Contacts: M. Gardeweg, SERNAGEOMIN, Santiago; S. Matthews, S. Sparks, and P. McLeod, Univ of Bristol; G. Bluth, GSFC.