Report on Nevado del Huila (Colombia) — May 1994

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 19, no. 5 (May 1994)

Managing Editor: Richard Wunderman.

Nevado del Huila (Colombia) Hundreds killed by seismically triggered mudflows

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 1994. Report on Nevado del Huila (Colombia) (Wunderman, R., ed.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 19:5. Smithsonian Institution. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.BGVN199405-351050

Nevado del Huila

Colombia

2.93°N, 76.03°W; summit elev. 5364 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

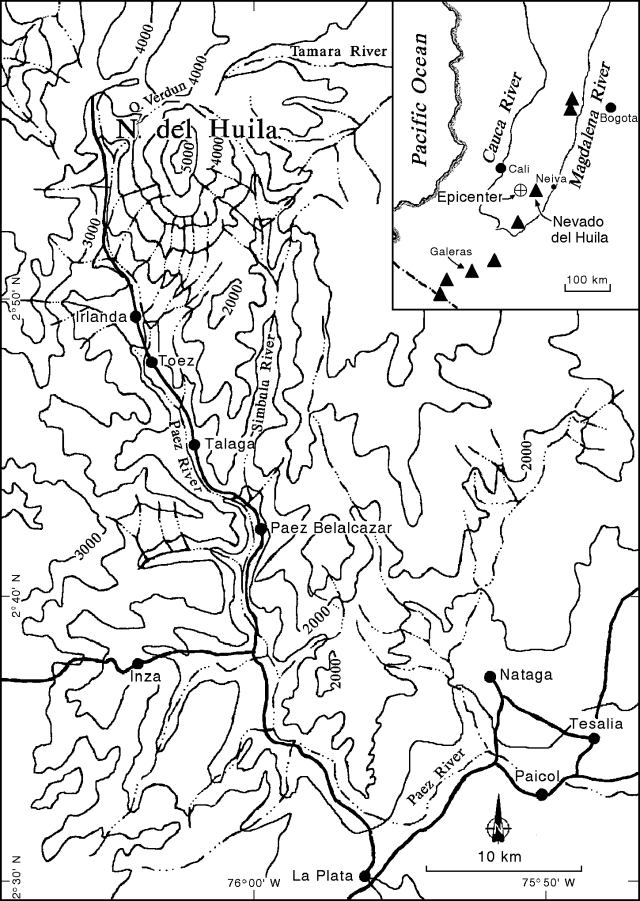

. . . earthquake-triggered mudflows swept down steep-walled valleys engulfing multiple villages and settlements (figure 1). The M 6.4 earthquake . . . took place at 1547 on 6 June, apparently falling along the Cauca Romeral fault. It disturbed a wide area, causing minor structural damage in Bogota, but more significant damage to 10 buildings in Cali (100 km W of the epicenter; see inset, figure 1). Near the epicenter, located 10-30 km W of the volcano, the earthquake destroyed at least 40 homes. The most catastrophic damage caused by the earthquake took place when Nevado del Huila released gravitationally unstable rock, snow, and ice down the volcano's slopes. These mudflows are the main focus of the rest of this report.

A . . . topographic map from a published hazard study (Cepeda, 1989) shows the rugged local geography (figure 1, note the contour interval, 500 m). The study also contains a second map that outlines areas of likely risk from lava flows and mudflows. To avoid confusion with the actual event we have omitted this second map, however, it shows the mudflows along drainages down the mountain continuing toward the SSE into the channel of the Paez river. The region of mudflow risk extends all the way to the map's margin near Paical (in the SE corner). Available information suggests the mudflows did basically follow the Paez river as anticipated.

According to a 9 June Reuters news report, "Graphic video images shot by a tourist . . . captured the moment when the huge brown-grey mass of mud roared down the valley, sweeping away trees, rocks, and houses in its path." According to witnesses, the mudflow reached 30-m high. In the wake of the mudflow, access to the area was cut off. Roads and bridges were damaged or blocked by mud, necessitating the use of helicopters. News reports repeatedly cited damage and casualties in the villages of Irlanda, Toez, Talaga, and Paez Belalcazar (figure 1).

A 7 June, UPI report quoted the archbishop of Paez Belalcazar, Jorge Garcia. On a flight over the area, he observed that the village of Toez had been "buried in mud," and "only the roof of the school can be seen." The same news report noted "There were no immediate reports of how many Toez residents managed to escape before the village was smothered, although some 500 people were thought to have been buried." The news report also related that in Paez Belalcazar ". . . 12 people were washed away by the rushing waters."

Overall, the number affected by the widely felt earthquake and the more restricted mudflows was estimated at 50,000. In terms of the mudflows alone, fatality estimates ranged from 253 to over 1,200 people. About 250 people, including many severely injured children, were evacuated by helicopter to hospitals in the provincial capital Neiva. Some 2,500 survivors were brought by helicopters to tent camps in La Plata.

A 6 June Reuters news report told of people hearing a "strong explosion" leading to initial confusion about whether the mudflows were triggered by an eruption or seismic loading. It was reported that geologists monitoring the volcano suggested the explosion may have come from an avalanche in the area.

Problems apparently went beyond the damage from the initial mudflows and subsequent limited access. For example, the 6 June news report stated that at one point: ". . . the river burst through a natural dam created by a mud and rock slide caused earlier by the quake." Other reports cited aftershocks and heavy rains contributing to ground instability, conditions that in some cases injured both survivors and rescue workers.

Reference. Cepeda, H., 1989, Catálogo de los volcanes activos de Colombia: Bol. Geol., v. 30, no. 3.

Geological Summary. Nevado del Huila, the highest peak in the Colombian Andes, is an elongated N-S-trending volcanic chain mantled by a glacier icecap. The andesitic-dacitic volcano was constructed within a 10-km-wide caldera. Volcanism at Nevado del Huila has produced six volcanic cones whose ages in general migrated from south to north. The high point of the complex is Pico Central. Two glacier-free lava domes lie at the southern end of the volcanic complex. The first historical activity was an explosive eruption in the mid-16th century. Long-term, persistent steam columns had risen from Pico Central prior to the next eruption in 2007, when explosive activity was accompanied by damaging mudflows.

Information Contacts: T. Casadevall, USGS; UPI; Reuters.