Report on Masaya (Nicaragua) — November 2018

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 43, no. 11 (November 2018)

Managing Editor: Edward Venzke.

Edited by Janine B. Krippner.

Masaya (Nicaragua) Lava lake activity continued from May through October 2018; lava lake lower than recent months

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 2018. Report on Masaya (Nicaragua) (Krippner, J.B., and Venzke, E., eds.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 43:11. Smithsonian Institution. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.BGVN201811-344100

Masaya

Nicaragua

11.9844°N, 86.1688°W; summit elev. 594 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Masaya is one of the most active volcanoes in Nicaragua and one of the few volcanoes on Earth to contain an active lava lake. The edifice has a caldera that contains the Masaya (also known as San Fernando), Nindirí, San Pedro, San Juan, and Santiago (currently active) craters. In recent years, activity has largely consisted of lava lake activity along with dilute plumes of gas with little ash. In 2012 an explosive event ejected ash and blocks. This report summarizes activity during May through October 2018 and is based on Instituto Nicaragüense de Estudios Territoriales (INETER) reports and satellite data.

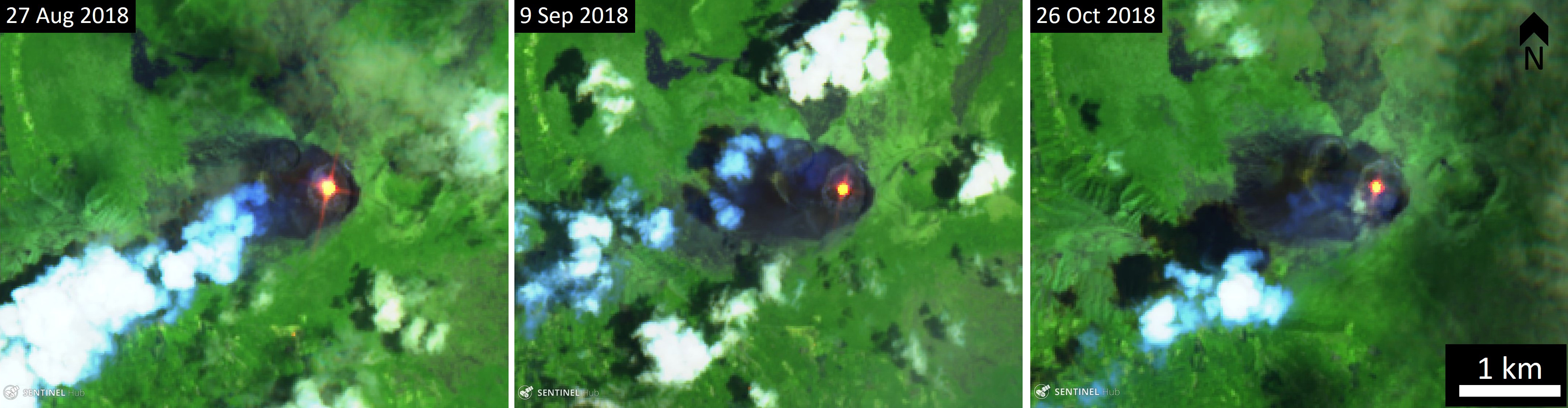

Reports issued from May through July 2018 noted that Masaya remained relatively calm. Sentinel-2 thermal satellite images show consistently high temperatures in the Santiago crater with the active lava lake present (figure 65).

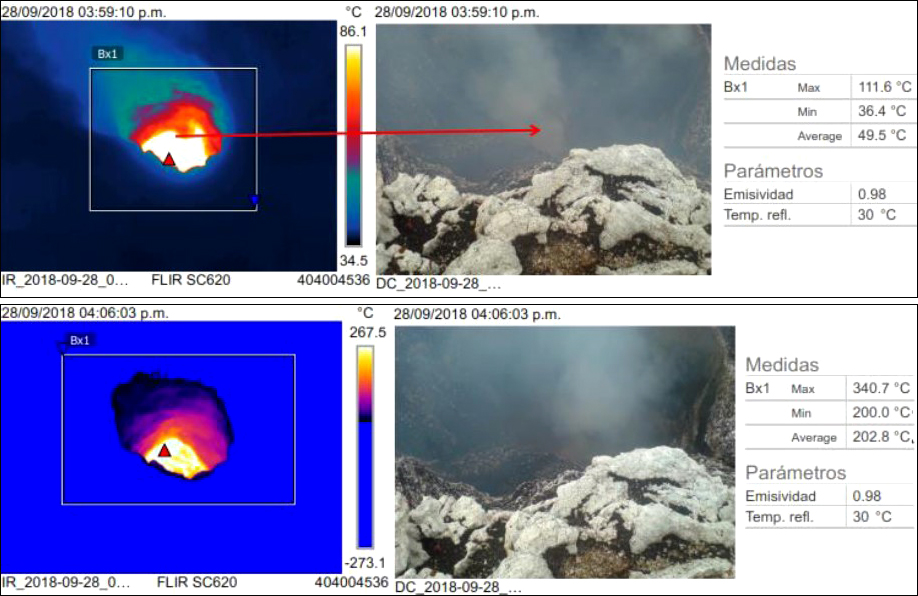

Reports from August through October 2018 indicated relatively low levels of activity. On 28 September the lava lake within the Santiago crater was observed with a lower surface than previous months. Fumarole temperatures up to 340°C were recorded (figure 66). Sentinel-2 thermal images show the large amount of heat consistently emanating from the active lava lake (figure 67). Sulfur dioxide was measured on 28 and 30 August with an average of 1,462 tons per day, a higher value than the average of 858 tons per day detected in February. Sulfur dioxide levels ranged from 967 to 1,708 tons per day on 11 September.

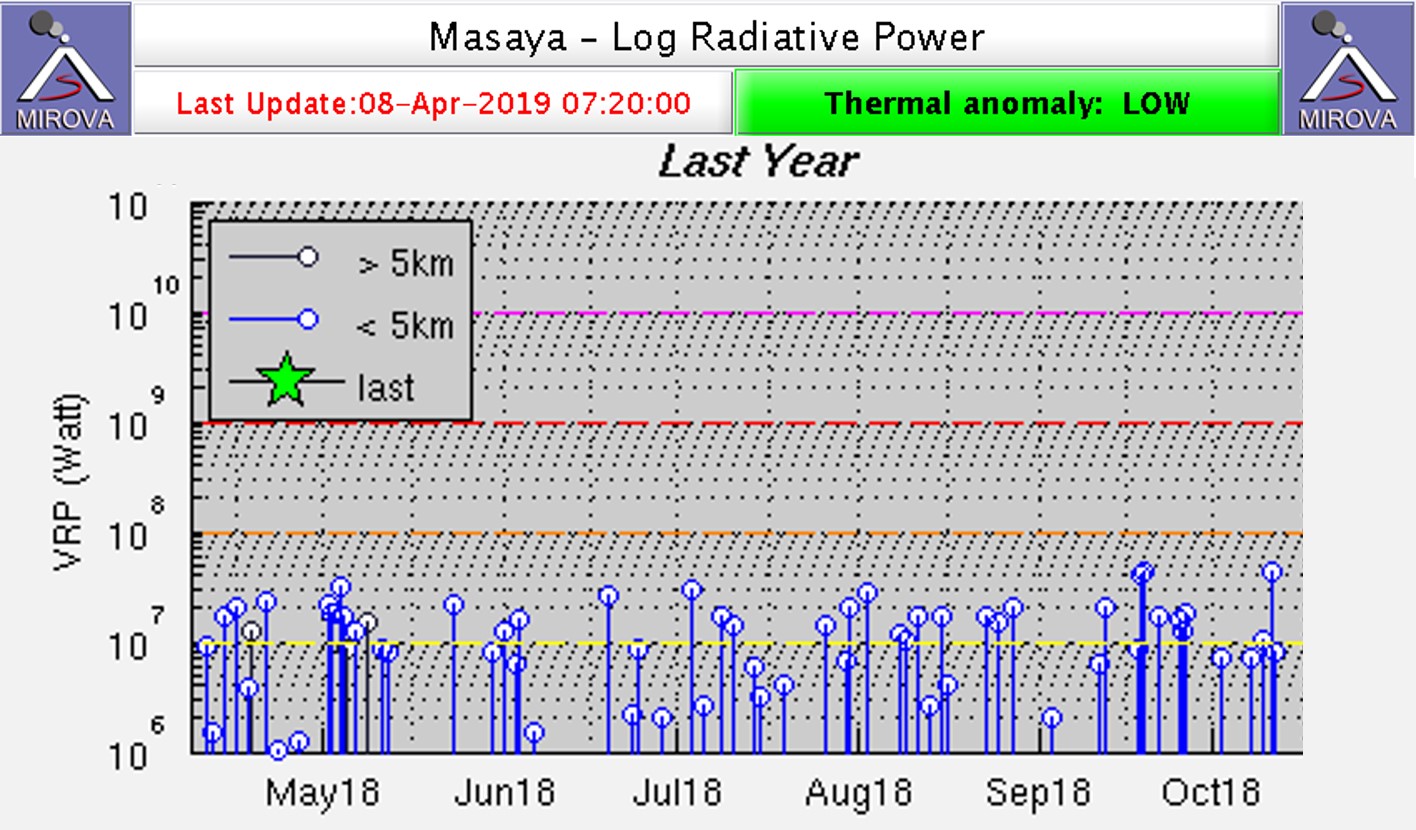

Overall, activity from May through October 2018 was relatively quiet with continued lava lake activity. The thermal energy detected by the MIROVA algorithm showed fluctuations but were consistent (figure 68). The MODVOLC algorithm for near-real-time thermal monitoring of global hotspots detected 4-8 anomalies per month for this period, which is lower than previous years (figure 69).

|

Figure 69. Thermal alerts for Masaya in May through October 2018. Courtesy of HIGP - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System. |

Geological Summary. Masaya volcano in Nicaragua has erupted frequently since the time of the Spanish Conquistadors, when an active lava lake prompted attempts to extract the volcano's molten "gold" until it was found to be basalt rock upon cooling. It lies within the massive Pleistocene Las Sierras caldera and is itself a broad, 6 x 11 km basaltic caldera with steep-sided walls up to 300 m high. The caldera is filled on its NW end by more than a dozen vents that erupted along a circular, 4-km-diameter fracture system. The Nindirí and Masaya cones, the source of observed eruptions, were constructed at the southern end of the fracture system and contain multiple summit craters, including the currently active Santiago crater. A major basaltic Plinian tephra erupted from Masaya about 6,500 years ago. Recent lava flows cover much of the caldera floor and there is a lake at the far eastern end. A lava flow from the 1670 eruption overtopped the north caldera rim. Periods of long-term vigorous gas emission at roughly quarter-century intervals have caused health hazards and crop damage.

Information Contacts: Instituto Nicaragüense de Estudios Territoriales (INETER), Apartado Postal 2110, Managua, Nicaragua (URL: http://webserver2.ineter.gob.ni/vol/dep-vol.html); Sentinel Hub Playground (URL: https://www.sentinel-hub.com/explore/sentinel-playground); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/).