Recently Published Bulletin Reports

Ioto (Japan) New eruption with discolored water, ejecta, and floating pumice during October-December 2023

Purace (Colombia) Gas-and-ash emission on 16 November 2023

Suwanosejima (Japan) Eruption plumes, crater incandescence, and occasional explosions during July-October 2023

Etna (Italy) Strombolian explosions, lava fountains, and lava flows during July-August 2023

Aira (Japan) Explosions, ash plumes, ash fall, and crater incandescence during July-October 2023

Nishinoshima (Japan) Gray emissions during October 2023

Kilauea (United States) Strong lava fountains, lava flows, and spatter at Halema’uma’u during January-September 2023

Tinakula (Solomon Islands) Continued lava flows and thermal activity during June through November 2023

Fuego (Guatemala) Daily explosions, gas-and-ash plumes, and block avalanches during August-November 2023

Santa Maria (Guatemala) Continuing lava effusion, explosions, ash plumes, and pyroclastic flows during August-November 2023

Karangetang (Indonesia) Incandescent avalanches, pyroclastic flows, and ash plumes during July-September 2023

Langila (Papua New Guinea) Intermittent thermal activity and few ash plumes during April-October 2023

Ioto

Japan

24.751°N, 141.289°E; summit elev. 169 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

New eruption with discolored water, ejecta, and floating pumice during October-December 2023

Ioto (Iwo-jima), located about 1,200 km S of Tokyo, lies within a 9-km-wide submarine caldera along the Izu-Bonin-Mariana volcanic arc. Previous eruptions date back to 1889 and have consisted of dominantly phreatic explosions, pumice deposits during 2001, and discolored water. A submarine eruption during July through December 2022 was characterized by discolored water, pumice deposits, and gas emissions (BGVN 48:01). This report covers a new eruption during October through December 2023, which consisted of explosions, black ejecta, discolored water, and floating pumice, based on information from the Japan Meteorological Association (JMA), the Japan Coast Guard (JCG), and satellite data.

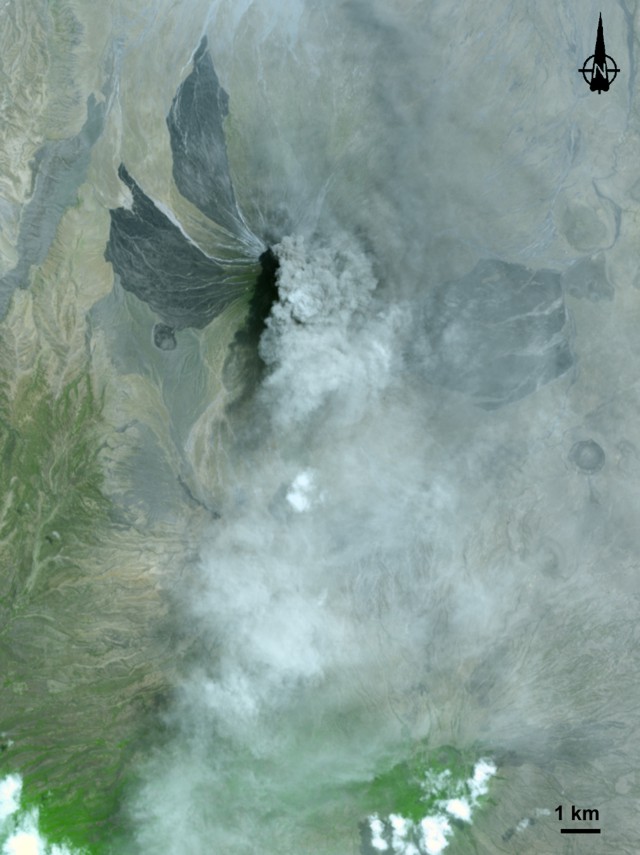

JMA reported that an eruption had been occurring offshore of Okinahama on the SE side of the island since 21 October, which was characterized by volcanic tremor, according to the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) Iwo Jima Air Base (figure 22). According to an 18 October satellite image a plume of discolored water at the site of this new eruption extended NE (figure 23). During an overflight conducted on 30 October, a vent was identified about 1 km off the coast of Okinahama. Observers recorded explosions every few minutes that ejected dark material about 20 m above the ocean and as high as 150 m. Ejecta from the vent formed a black-colored island about 100 m in diameter, according to observations conducted from the air by the Earthquake Research Institute of the University of Tokyo in cooperation with the Mainichi newspaper (figure 24). Occasionally, large boulders measuring more than several meters in size were also ejected. Observations from the Advanced Land Observing Satellite Daichi-2 and Sentinel-2 satellite images also confirmed the formation of this island (figure 23). Brown discolored water and floating pumice were present surrounding the island.

The eruption continued during November. During an overflight on 3 November observers photographed the island and noted that material was ejected 169 m high, according to a news source. Explosions gradually became shorter, and, by the 3rd, they occurred every few seconds; dark and incandescent material were ejected about 800 m above the vent. On 4 November eruptions were accompanied by explosive sounds. Floating, brown-colored pumice was present in the water surrounding the island. There was a brief increase in the number of volcanic earthquakes during 8-14 November and 24-25 November. The eruption temporarily paused during 9-11 November and by 12 November eruptions resumed to the W of the island. On 10 November dark brown-to-dark yellow-green discolored water and a small amount of black floating material was observed (figure 25). A small eruption was reported on 18 November off the NE coast of the island, accompanied by white gas-and-steam plumes (figure 23). Another pause was recorded during 17-19 November, which then resumed on 20 November and continued erupting intermittently. According to a field survey conducted by the National Institute for Disaster Prevention Science and Technology on 19 November, a 30-m diameter crater was visible on the NE coast where landslides, hot water, and gray volcanic ash containing clay have occurred and been distributed previously. Erupted blocks about 10 cm in diameter were distributed about 90-120 m from the crater. JCG made observations during an overflight on 23 November and reported a phreatomagmatic eruption. Explosions at the main vent generated dark gas-and-ash plumes that rose to 200 m altitude and ejected large blocks that landed on the island and in the ocean (figure 26). Discolored water also surrounded the island. The size of the new island had grown to 450 m N-S x 200 m E-W by 23 November, according to JCG.

The eruption continued through 11 December, followed by a brief pause in activity, which then resumed on 31 December, according to JMA. Intermittent explosions produced 100-m-high black plumes at intervals of several minutes to 30 minutes during 1-10 December. Overflights were conducted on 4 and 15 December and reported that the water surrounding the new island was discolored to dark brown-to-dark yellow-green (figure 27). No floating material was reported during this time. In comparison to the observations made on 23 November, the new land had extended N and part of it had eroded away. In addition, analysis by the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan using SAR data from Daichi-2 also confirmed that the area of the new island continued to decrease between 4 and 15 December. Ejected material combined with wave erosion transformed the island into a “J” shape, 500-m-long and with the curved part about 200 m offshore of Ioto. The island was covered with brown ash and blocks, and the surrounding water was discolored to greenish-brown and contained an area of floating pumice. JCG reported from an overflight on 4 December that volcanic ash-like material found around the S vent on the NE part of the island was newly deposited since 10 November (figure 28). By 15 December the N part of the “J” shaped island had separated and migrated N, connecting to the Okinahama coast and the curved part of the “J” had eroded into two smaller islands (figure 27).

References. Ukawa, M., Fujita, E., Kobayashi, T., 2002, Recent volcanic activity of Iwo Jima and the 2001 eruption, Monthly Chikyu, Extra No. 39, 157-164.

Geologic Background. Ioto, in the Volcano Islands of Japan, lies within a 9-km-wide submarine caldera. The volcano is also known as Ogasawara-Iojima to distinguish it from several other "Sulfur Island" volcanoes in Japan. The triangular, low-elevation, 8-km-long island narrows toward its SW tip and has produced trachyandesitic and trachytic rocks that are more alkalic than those of other volcanoes in this arc. The island has undergone uplift for at least the past 700 years, accompanying resurgent doming of the caldera; a shoreline landed upon by Captain Cook's surveying crew in 1779 is now 40 m above sea level. The Motoyama plateau on the NE half of the island consists of submarine tuffs overlain by coral deposits and forms the island's high point. Many fumaroles are oriented along a NE-SW zone cutting through Motoyama. Numerous recorded phreatic eruptions, many from vents on the W and NW sides of the island, have accompanied the uplift.

Information Contacts: Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), 1-3-4 Otemachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8122, Japan (URL: http://www.jma.go.jp/jma/indexe.html); Japan Coast Guard (JCG) Volcano Database, Hydrographic and Oceanographic Department, 3-1-1, Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8932, Japan (URL: https://www1.kaiho.mlit.go.jp/GIJUTSUKOKUSAI/kaiikiDB/kaiyo22-2.htm); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/); Asahi, 5-3-2, Tsukiji, Chuo Ward, Tokyo, 104-8011, Japan (URL: https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/15048458).

Purace (Colombia) — December 2023  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Purace

Colombia

2.3095°N, 76.3948°W; summit elev. 4650 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Gas-and-ash emission on 16 November 2023

Puracé, located in Colombia, is a stratovolcano that contains a 500-m-wide summit crater. It is part of the Los Coconucos volcanic chain that is a NW-SE trending group of seven cones and craters. The most recent eruption occurred during March 2022 that was characterized by frequent seismicity and gas-and-steam emissions (BGVN 47:06). This report covers a brief eruption during November 2023 based on monthly reports from the Popayán Observatory, part of the Servicio Geologico Colombiano (SGC).

Activity during November 2022 through November 2023 primarily consisted of seismicity: VT-type events, LP-type events, HB-type events, and TR-type events (table 4). Maximum sulfur dioxide values were measured weekly and ranged from 259-5,854 tons per day (t/d) during November 2022 through April 2023. White gas-and-steam emissions were also occasionally reported.

SGC issued a report on 25 October that noted a significant increase in the number of earthquakes associated with rock fracturing. These earthquakes were located SE of the crater between Puracé and Piocollo at depths of 1-4 km. There were no reported variations in sulfur dioxide values, but SGC noted high carbon dioxide values, compared to those recorded in the first half of 2023.

SGC reported that at 1929 on 16 November the seismic network detected a signal that was possibly associated with a gas-and-ash emission, though it was not confirmed in webcam images due to limited visibility. On 17 November an observer confirmed ash deposits on the N flank. Webcam images showed an increase in degassing both inside the crater and from the NW flank, rising 700 m above the crater.

Table 4. Seismicity at Puracé during November 2022-November 2023. Volcano-tectonic (VT), long-period (LP), hybrid (HB), and tremor (TR) events are reported each month. Courtesy of SGC.

| Month |

Volcano-tectonic |

Long-period |

Hybrid |

Tremor |

| Nov 2022 |

429 |

2,023 |

5 |

831 |

| Dec 2022 |

423 |

1,390 |

9 |

834 |

| Jan 2023 |

719 |

1,622 |

0 |

957 |

| Feb 2023 |

598 |

1,701 |

2 |

1,124 |

| Mar 2023 |

331 |

2,408 |

147 |

607 |

| Apr 2023 |

614 |

4,427 |

33 |

148 |

| May 2023 |

620 |

3,717 |

170 |

109 |

| Jun 2023 |

467 |

3,293 |

86 |

148 |

| Jul 2023 |

1,116 |

5,809 |

183 |

542 |

| Aug 2023 |

692 |

2,927 |

94 |

321 |

| Sep 2023 |

887 |

1,505 |

82 |

848 |

| Oct 2023 |

2,373 |

2,949 |

135 |

692 |

| Nov 2023 |

1,212 |

2,302 |

69 |

293 |

Geologic Background. Puracé is an active andesitic volcano with a 600-m-diameter summit crater at the NW end of the Los Coconucos Volcanic Chain. This volcanic complex includes nine composite and five monogenetic volcanoes, extending from the Puracé crater more than 6 km SE to the summit of Pan de Azúcar stratovolcano. The dacitic massif which the complex is built on extends about 13 km NW-SE and 10 km NE-SW. Frequent small to moderate explosive eruptions reported since 1816 CE have modified the morphology of the summit crater, with the largest eruptions in 1849, 1869, and 1885.

Information Contacts: Servicio Geologico Colombiano (SGC), Diagonal 53 No. 34-53 - Bogotá D.C., Colombia (URL: https://www.sgc.gov.co/volcanes).

Suwanosejima (Japan) — December 2023  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

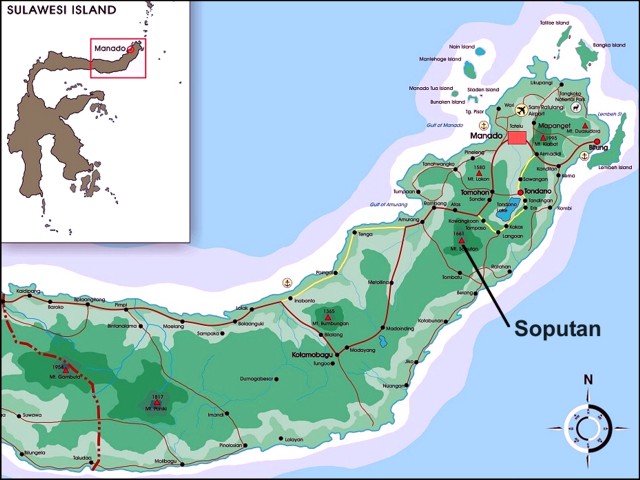

Suwanosejima

Japan

29.638°N, 129.714°E; summit elev. 796 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

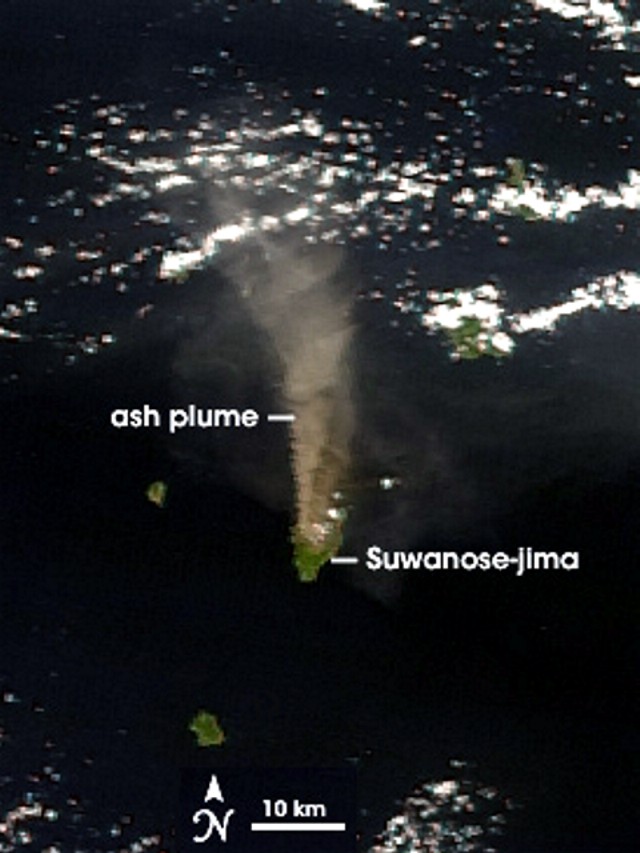

Eruption plumes, crater incandescence, and occasional explosions during July-October 2023

Suwanosejima is an 8-km-long island that consists of a stratovolcano and two active summit craters, located in the northern Ryukyu Islands, Japan. Volcanism over the past century has been characterized by Strombolian explosions, ash plumes, and ashfall. The current eruption began in October 2004 and has more recently consisted of frequent eruption plumes, explosions, and incandescent ejecta (BGVN 48:07). This report covers similar activity of ash plumes, explosions, and crater incandescence during July through October 2023 using monthly reports from the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) and satellite data.

Thermal activity during the reporting period was relatively low; only one low-power thermal anomaly was detected during mid-July and one during early August, based on a MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) Log Radiative Power graph of the MODIS thermal anomaly data. On two clear weather days, a thermal anomaly was visible in infrared satellite images (figure 81).

Low-level activity was reported at the Otake crater during July and no explosions were detected. Eruption plumes rose as high as 1.8 km above the crater. On 13 July an ash plume rose 1.7 km above the crater rim, based on a webcam image. During the night of the 28th crater incandescence was visible in a webcam image. An eruptive event reported on 31 July produced an eruption plume that rose 2.1 km above the crater. Seismicity consisted of 11 volcanic earthquakes on the W flank, the number of which had decreased compared to June (28) and 68 volcanic earthquakes near the Otake crater, which had decreased from 722 in the previous month. According to observations conducted by the University of Tokyo Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Toshima Village, and JMA, the amount of sulfur dioxide emissions released during the month was 400-800 tons per day (t/d).

Eruptive activity in the Otake crater continued during August and no explosions were reported. An eruptive event produced a plume that rose 1 km above the crater at 1447 on 12 August. Subsequent eruptive events were recorded at 0911 on 16 August, at 1303 on 20 August, and at 0317 on 21 August, which produced ash plumes that rose 1-1.1 km above the crater and drifted SE, SW, and W. On 22 August an ash plume was captured in a webcam image rising 1.4 km above the crater (figure 82). Multiple eruptive events were detected on 25 August at 0544, 0742, 0824, 1424, and 1704, which generated ash plumes that rose 1.1-1.2 km above the crater and drifted NE, W, and SW. On 28 August a small amount of ashfall was observed as far as 1.5 km from the crater. There were 17 volcanic earthquakes recorded on the W flank of the volcano and 79 recorded at the Otake crater during the month. The amount of sulfur dioxide emissions released during the month was 400-800 t/d.

Activity continued at the Otake crater during September. Occasionally, nighttime crater incandescence was observed in webcam images and ashfall was reported. An eruptive event at 1949 on 4 September produced an ash plume that rose 1 km above the crater and drifted SW. On 9 September several eruption events were detected at 0221, 0301, and 0333, which produced ash plumes that rose 1.1-1.4 km above the crater rim and drifted W; continuous ash emissions during 0404-0740 rose to a maximum height of 2 km above the crater rim (figure 83). More eruptive events were reported at 1437 on 10 September, at 0319 on 11 September, and at 0511 and 1228 on 15 September, which generated ash plumes that rose 1-1.8 km above the crater. During 25, 27, and 30 September, ash plumes rose as high as 1.3 km above the crater rim. JMA reported that large blocks were ejected as far as 300 m from the center of the crater. There were 18 volcanic earthquakes detected beneath the W flank and 82 volcanic earthquakes detected near the Otake crater. The amount of sulfur dioxide released during the month ranged from 600 to 1,600 t/d.

Activity during early-to-mid-October consisted of occasional explosions, a total number of 13, and ash plumes that rose as high as 1.9 km above the Otake crater rim on 29 October (figure 84). These explosions are the first to have occurred since June 2023. Continuous ash emissions were reported during 0510-0555 on 1 October. Explosions were recorded at 0304, 2141, and 2359 on 2 October, at 0112 on 3 October, and at 1326 on 6 October, which produced ash plumes that rose as high as 1 km above the crater rim and drifted SW and W. An explosion was noted at 0428 on 3 October, but emission details were unknown. A total of eight explosions were recorded by the seismic network at 1522 on 14 October, at 0337, 0433, 0555, 1008, and 1539 on 15 October, and at 0454 and 0517 on 16 October. Ash plumes from these explosions rose as high as 900 m above the crater and drifted SE. Eruptive events during 25-27 and 29-30 October generated plumes that rose as high as 1.9 km above the crater and drifted SE, S, and SW. Ash was deposited in Toshima village (3.5 km SSW). Eruptive activity occasionally ejected large volcanic blocks as far as 600 m from the crater. Nighttime crater incandescence was visible in webcams. Intermittent ashfall was reported as far as 1.5 km from the crater. There were 43 volcanic earthquakes detected on the W flank during the month, and 184 volcanic earthquakes detected near the Otake crater. The amount of sulfur dioxide emitted ranged between 400 and 900 t/d.

Geologic Background. The 8-km-long island of Suwanosejima in the northern Ryukyu Islands consists of an andesitic stratovolcano with two active summit craters. The summit is truncated by a large breached crater extending to the sea on the E flank that was formed by edifice collapse. One of Japan's most frequently active volcanoes, it was in a state of intermittent Strombolian activity from Otake, the NE summit crater, between 1949 and 1996, after which periods of inactivity lengthened. The largest recorded eruption took place in 1813-14, when thick scoria deposits covered residential areas, and the SW crater produced two lava flows that reached the western coast. At the end of the eruption the summit of Otake collapsed, forming a large debris avalanche and creating an open collapse scarp extending to the eastern coast. The island remained uninhabited for about 70 years after the 1813-1814 eruption. Lava flows reached the eastern coast of the island in 1884. Only about 50 people live on the island.

Information Contacts: Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), 1-3-4 Otemachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8122, Japan (URL: http://www.jma.go.jp/jma/indexe.html); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Etna

Italy

37.748°N, 14.999°E; summit elev. 3357 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Strombolian explosions, lava fountains, and lava flows during July-August 2023

Etna, located on the Italian island of Sicily, has had documented eruptions dating back to 1500 BCE. Activity typically originates from multiple cones at the summit, where several craters have formed and evolved. The currently active craters are Northeast Crater (NEC), Voragine (VOR), and Bocca Nuova (BN), and the Southeast Crater (SEC); VOR and BN were previously referred to as the “Central Crater”. The original Southeast crater formed in 1978, and a second eruptive site that opened on its SE flank in 2011 was named the New Southeast Crater (NSEC). Another eruptive site between the SEC and NSEC developed during early 2017 and was referred to as the "cono della sella" (saddle cone). The current eruption period began in November 2022 and has been characterized by intermittent Strombolian activity, lava flows, and ash plumes (BGVN 48:08). This report updates activity during July through October 2023, which includes primarily gas-and-steam emissions; during July and August Strombolian explosions, lava fountains, and lava flows were reported, based on weekly and special reports by the Osservatorio Etneo (OE), part of the Catania Branch of Italy's Istituo Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologica (INGV) and satellite data.

Variable fumarolic degassing was reported at all summit craters (BN, VOR, NEC, and SEC) throughout the entire reporting period (table 15). The MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) volcano hotspot detection system based on the analysis of MODIS data showed frequent low-to-moderate power thermal anomalies during the reporting period (figure 399). During mid-August there was a pulse in activity that showed an increase in the power of the anomalies due to Strombolian activity, lava fountains, and lava flows. Infrared satellite imagery captured strong thermal anomalies at the central and southeast summit crater areas (figure 400). Accompanying thermal activity were occasional sulfur dioxide plumes that exceeded 2 Dobson Units (DUs) recorded by the TROPOMI instrument on the Sentinel-5P satellite (figure 401).

Table 15. Summary of activity at the four primary crater areas at the summit of Etna during July-October 2023. Information is from INGV weekly reports.

| Month |

Bocca Nuova (BN) |

Voragine (VOR) |

Northeast Crater (NEC) |

Southeast Crater (SEC) |

| Jul 2023 |

Continuous degassing. |

No observations. |

Weak gas emissions. |

Continuous degassing. Sporadic and weak-to-moderate ash emissions. Strombolian explosions. |

| Aug 2023 |

Continuous degassing. |

No observations. |

No observations. |

Continuous degassing. Occasional ash emissions. Strombolian activity, lava fountaining, and lava flows. |

| Sep 2023 |

Variable degassing. Crater incandescence. |

Weak fumarolic activity. |

Weak fumarolic activity. |

Variable degassing. |

| Oct 2023 |

Continuous degassing. |

Weak fumarolic activity. |

Weak fumarolic activity. |

Continuous degassing. |

Activity during July and August was relatively low and mainly consisted of degassing at the summit craters, particularly at SEC and BN. Cloudy weather prevented clear views of the summit during early July. During the night of 2 July some crater incandescence was visible at SEC. Explosive activity resumed at SEC during 9-10 July, which was characterized by sporadic and weak ash emissions that rapidly dispersed in the summit area (figure 402). INGV reported moderate Strombolian activity began at 2034 on 14 July and was confined to the inside of the crater and fed by a vent located in the E part of SEC. An ash emission was detected at 2037. A new vent opened on 15 July in the SE part of BN and began to produce continuous gas-and-steam emissions. During an inspection carried out on 28 July pulsating degassing, along with audible booms, were reported at two active vents in BN. Vigorous gas-and-steam emissions intermittently generated rings. On rare occasions, fine, reddish ash was emitted from BN1 and resuspended by the gas-and-steam emissions.

Around 2000 on 13 August INGV reported a sudden increase in volcanic tremor amplitude. Significant infrasonic activity coincided with the tremor increase. Incandescent flashes were visible through the cloud cover in webcam images of SEC (figure 403). Strombolian activity at SEC began to gradually intensify starting at 2040 as seismicity continued to increase. The Aviation Color Code (ACC) was raised to Yellow (the second lowest-level on a four-color scale) at 2126 and then to Orange (the second highest-level on a four-color scale) at 2129 due to above-background activity. The activity rapidly transitioned from Strombolian activity to lava fountains around 2333 that rose 300-400 m above the crater (figure 403). Activity was initially focused on the E vent of the crater, but then the vent located above the S flank of the cone also became active. A lava flow from this vent traveled SW into the drainage created on 10 February 2022, overlapping with previous flows from 10 and 21 February 2022 and 21 May 2023, moving between Monte Barbagallo and Monte Frumento Supino (figure 404). The lava flow was 350 m long, oriented NNE-SSW, and descended to an elevation of 2.8 km. Flows covered an area of 300,000 m2 and had an estimated volume of 900,000 m3. The ACC was raised to Red at 2241 based on strong explosive activity and ashfall in Rifugio Sapienza-Piano Vetore at 1.7 km elevation on the S flank. INGV reported that pyroclastic flows accompanied this activity.

Activity peaked between 0240 and 0330 on 14 August, when roughly 5-6 vents erupted lava fountains from the E to SW flank of SEC. The easternmost vents produced lava fountains that ejected material strongly to the E, which caused heavy fallout of incandescent pyroclastic material on the underlying flank, triggering small pyroclastic flows. This event was also accompanied by lightning both in the ash column and in the ash clouds that were generated by the pyroclastic flows. A fracture characterized by a series of collapse craters (pit craters) opened on the upper SW flank of SEC. An ash cloud rose a few kilometers above the crater and drifted S, causing ash and lapilli falls in Rifugio Sapienza and expanding toward Nicolosi, Mascalucia, Catania, and up to Syracuse. Ashfall resulted in operational problems at the Catania airport (50 km S), which lasted from 0238 until 2000. By 0420 the volcanic tremor amplitude values declined to background levels. After 0500 activity sharply decreased, although the ash cloud remained for several hours and drifted S. By late morning, activity had completely stopped. The ACC was lowered to Orange as volcanic ash was confined to the summit area. Sporadic, minor ash emissions continued throughout the day. At 1415 the ACC was lowered to Yellow and then to Green at 1417.

During the night of 14-15 August only occasional flashes were observed, which were more intense during avalanches of material inside the eruptive vents. Small explosions were detected at SEC at 2346 on 14 August and at 0900 on 26 August that each produced ash clouds which rapidly dispersed into the atmosphere (figure 405). According to a webcam image, an explosive event detected at 2344 at SEC generated a modest ash cloud that was rapidly dispersed by winds. The ACC was raised to Yellow at 2355 on 14 August due to increasing unrest and was lowered to Green at 0954 on 15 August.

Activity during September and October was relatively low and mainly characterized by variable degassing from BN and SEC. Intense, continuous, and pulsating degassing was accompanied by roaring sounds and flashes of incandescence at BN both from BN1 and the new pit crater that formed during late July (figure 406). The degassing from the new pit crater sometimes emitted vapor rings. Cloudy weather during 6-8 September prevented observations of the summit craters .

Geologic Background. Mount Etna, towering above Catania on the island of Sicily, has one of the world's longest documented records of volcanism, dating back to 1500 BCE. Historical lava flows of basaltic composition cover much of the surface of this massive volcano, whose edifice is the highest and most voluminous in Italy. The Mongibello stratovolcano, truncated by several small calderas, was constructed during the late Pleistocene and Holocene over an older shield volcano. The most prominent morphological feature of Etna is the Valle del Bove, a 5 x 10 km caldera open to the east. Two styles of eruptive activity typically occur, sometimes simultaneously. Persistent explosive eruptions, sometimes with minor lava emissions, take place from one or more summit craters. Flank vents, typically with higher effusion rates, are less frequently active and originate from fissures that open progressively downward from near the summit (usually accompanied by Strombolian eruptions at the upper end). Cinder cones are commonly constructed over the vents of lower-flank lava flows. Lava flows extend to the foot of the volcano on all sides and have reached the sea over a broad area on the SE flank.

Information Contacts: Sezione di Catania - Osservatorio Etneo, Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV), Sezione di Catania, Piazza Roma 2, 95123 Catania, Italy (URL: http://www.ct.ingv.it/it/); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); NASA Global Sulfur Dioxide Monitoring Page, Atmospheric Chemistry and Dynamics Laboratory, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (NASA/GSFC), 8800 Greenbelt Road, Goddard MD 20771, USA (URL: https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Aira

Japan

31.5772°N, 130.6589°E; summit elev. 1117 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Explosions, ash plumes, ash fall, and crater incandescence during July-October 2023

Aira caldera, located in the northern half of Kagoshima Bay, Japan, contains the post-caldera Sakurajima volcano. Eruptions typically originate from the Minamidake crater, and since the 8th century, ash deposits have been recorded in the city of Kagoshima (10 km W), one of Kyushu’s largest cities. The Minamidake summit cone and crater has had persistent activity since 1955; the Showa crater on the E flank has also been intermittently active since 2006. The current eruption period began during March 2017 and has recently been characterized by intermittent explosions, eruption plumes, and ashfall (BGVN 48:07). This report updates activity during July through October 2023 and describes explosive events, ash plumes, nighttime crater incandescence, and ashfall, according to monthly activity reports from the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) and satellite data.

Thermal activity remained at low levels during this reporting period, according to the MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) system (figure 149). There was a slight increase in the number of anomalies during September through October. Occasional thermal anomalies were visible in infrared satellite images mainly at the Minamidake crater (Vent A is located to the left and Vent B is located to the right) (figure 150).

Table 30. Number of monthly explosive events, days of ashfall, area of ash covered, and sulfur dioxide emissions from Sakurajima’s Minamidake crater at Aira during July-October 2023. Note that smaller ash events are not listed. Ashfall days were measured at Kagoshima Local Meteorological Observatory and ashfall amounts represent material covering all the Kagoshima Prefecture. Data courtesy of JMA monthly reports.

| Month |

Explosive events |

Days of ashfall |

Ashfall amount (g/m2) |

SO2 emissions (tons/day) |

| Jul 2023 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

1,600-3,200 |

| Aug 2023 |

3 |

10 |

7 |

1,800-3,300 |

| Sep 2023 |

3 |

7 |

3 |

1,600-2,300 |

| Oct 2023 |

33 |

8 |

61 |

2,200-4,200 |

JMA reported that during July, there were eight eruptions, three of which were explosion events in the Showa crater. Large blocks were ejected as far as 600 m from the Showa crater. Very small eruptions were occasionally reported at the Minamidake crater. Nighttime incandescence was observed in both the Showa and Minamidake crater. Explosions were reported on 16 July at 2314 and on 17 July at 1224 and at 1232 (figure 151). Resulting eruption plumes rose 700-2,500 m above the crater and drifted N. On 23 July the number of volcanic earthquakes on the SW flank of the volcano increased. A strong Mw 3.1 volcanic earthquake was detected at 1054 on 26 July. The number of earthquakes recorded throughout the month was 545, which markedly increased from 73 in June. No ashfall was observed at the Kagoshima Regional Meteorological Observatory during July. According to a field survey conducted during the month, the daily amount of sulfur dioxide emissions was 1,600-3,200 tons per day (t/d).

There were three eruptions reported at the Minamidake crater during August, each of which were explosive. The explosions occurred on 9 August at 0345, on 13 August at 2205, and on 31 August at 0640, which generated ash plumes that rose 800-2,000 m above the crater and drifted W. There were two eruptions detected at Showa crater; on 4 August at 2150 ejecta traveled 800 m from the Showa crater and associated eruption plumes rose 2.3 km above the crater. The explosion at 2205 on 13 August generated an ash plume that rose 2 km above the crater and was accompanied by large blocks that were ejected 600 m from the Minamidake crater (figure 152). Nighttime crater incandescence was visible in a high-sensitivity surveillance camera at both craters. Seismicity consisted of 163 volcanic earthquakes, 84 of which were detected on the SW flank. According to the Kagoshima Regional Meteorological Observatory there was a total of 7 g/m2 of ashfall over the course of 10 days during the month. According to a field survey, the daily amount of sulfur dioxide emitted was 1,800-3,300 t/d.

During September, four eruptions were reported, three of which were explosion events. These events occurred at 1512 on 9 September, at 0018 on 11 September, and at 2211 on 13 September. Resulting ash plumes generally rose 800-1,100 m above the crater. An explosion produced an ash plume at 2211 on 13 September that rose as high as 1.7 km above the crater. Large volcanic blocks were ejected 600 m from the Minamidake crater. Smaller eruptions were occasionally observed at the Showa crater. Nighttime crater incandescence was visible at the Minamidake crater. Seismicity was characterized by 68 volcanic earthquakes, 28 of which were detected beneath the SW flank. According to the Kagoshima Regional Meteorological Observatory there was a total of 3 g/m2 of ashfall over the course of seven days during the month. A field survey reported that the daily amount of sulfur dioxide emitted was 1,600-2,300 t/d.

Eruptive activity during October consisted of 69 eruptions, 33 of which were described as explosive. These explosions occurred during 4 and 11-21 October and generated ash plumes that rose 500-3,600 m above the crater and drifted S, E, SE, and N. On 19 October at 1648 an explosion generated an ash plume that rose 3.6 km above the crater (figure 153). No eruptions were reported in the Showa crater; white gas-and-steam emissions rose 100 m above the crater from a vent on the N flank. Nighttime incandescence was observed at the Minamidake crater. On 24 October an eruption was reported from 0346 through 0430, which included an ash plume that rose 3.4 km above the crater. Ejected blocks traveled 1.2 km from the Minamidake crater. Following this eruption, small amounts of ashfall were observed from Arimura (4.5 km SE) and a varying amount in Kurokami (4 km E) (figure 154). The number of recorded volcanic earthquakes during the month was 190, of which 14 were located beneath the SW flank. Approximately 61 g/m2 of ashfall was reported over eight days of the month. According to a field survey, the daily amount of sulfur dioxide emitted was 2,200-4,200 t/d.

Geologic Background. The Aira caldera in the northern half of Kagoshima Bay contains the post-caldera Sakurajima volcano, one of Japan's most active. Eruption of the voluminous Ito pyroclastic flow accompanied formation of the 17 x 23 km caldera about 22,000 years ago. The smaller Wakamiko caldera was formed during the early Holocene in the NE corner of the caldera, along with several post-caldera cones. The construction of Sakurajima began about 13,000 years ago on the southern rim and built an island that was joined to the Osumi Peninsula during the major explosive and effusive eruption of 1914. Activity at the Kitadake summit cone ended about 4,850 years ago, after which eruptions took place at Minamidake. Frequent eruptions since the 8th century have deposited ash on the city of Kagoshima, located across Kagoshima Bay only 8 km from the summit. The largest recorded eruption took place during 1471-76.

Information Contacts: Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), 1-3-4 Otemachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8122, Japan (URL: http://www.jma.go.jp/jma/indexe.html); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Nishinoshima (Japan) — November 2023  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Nishinoshima

Japan

27.247°N, 140.874°E; summit elev. 100 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Gray emissions during October 2023

Nishinoshima is a small island in the Ogasawara Arc, about 1,000 km S of Tokyo, Japan. It contains prominent submarine peaks to the S, W, and NE. Recorded eruptions date back to 1973, with the current eruption period beginning in October 2022. Eruption plumes and fumarolic activity characterize recent activity (BGVN 48:10). This report covers the end of the eruption for September through October 2023, based on information from monthly reports of the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) monthly reports, and satellite data.

No eruptive activity was reported during September 2023, although JMA noted that the surface temperature was slightly elevated compared to the surrounding area since early March 2023. The Japan Coast Guard (JCG) conducted an overflight on 20 September and reported white gas-and-steam plumes rising 3 km above the central crater of the pyroclastic cone, as well as multiple white gas-and-steam emissions emanating from the N, E, and S flanks of the crater to the coastline. In addition, dark reddish brown-to-green discolored water was distributed around almost the entire circumference of the island.

Similar low-level activity was reported during October. Multiple white gas-and-steam emissions rose from the N, E, and S flanks of the central crater of the pyroclastic cone and along the coastline; these emissions were more intense compared to the previous overflight observations. Dark reddish brown-to-green discolored water remained visible around the circumference of the island. On 4 October aerial observations by JCG showed a small eruption consisting of continuous gas-and-steam emissions emanating from the central crater, with gray emissions rising to 1.5 km altitude (figure 129). According to observations from the marine weather observation vessel Keifu Maru on 26 October, white gas-and-steam emissions persisted from the center of the pyroclastic cone, as well as from the NW, SW, and SE coasts of the island for about five minutes. Slightly discolored water was visible up to about 1 km.

Frequent low-to-moderate power thermal anomalies were recorded in the MIROVA graph (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) during September (figure 130). Occasional anomalies were detected during October, and fewer during November through December. A thermal anomaly was visible in the crater using infrared satellite imagery on 6, 8, 11, 16, 18, 21, and 23 September and 8, 13, 21, 26, and 28 October (figure 131).

Geologic Background. The small island of Nishinoshima was enlarged when several new islands coalesced during an eruption in 1973-74. Multiple eruptions that began in 2013 completely covered the previous exposed surface and continued to enlarge the island. The island is the summit of a massive submarine volcano that has prominent peaks to the S, W, and NE. The summit of the southern cone rises to within 214 m of the ocean surface 9 km SSE.

Information Contacts: Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), 1-3-4 Otemachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8122, Japan (URL: http://www.jma.go.jp/jma/indexe.html); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Kilauea (United States) — October 2023  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Kilauea

United States

19.421°N, 155.287°W; summit elev. 1222 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Strong lava fountains, lava flows, and spatter at Halema’uma’u during January-September 2023

Kīlauea is on the island of Hawai’i and overlaps the E flank of the Mauna Loa volcano. Its East Rift Zone (ERZ) has been intermittently active for at least 2,000 years. An extended eruption period began in January 1983 and was characterized by open lava lakes and lava flows from the summit caldera and the East Rift Zone. During May 2018 magma migrated into the Lower East Rift Zone (LERZ) and opened 24 fissures along a 6-km-long NE-trending fracture zone that produced lava flows traveling in multiple directions. As lava emerged from the fissures, the lava lake at Halema'uma'u drained and explosions sent ash plumes to several kilometers altitude (BGVN 43:10).

The current eruption period started during September 2021 and has been characterized by low-level lava effusions in the active Halema’uma’u lava lake (BGVN 48:01). This report covers three notable eruption periods during February, June, and September 2023 consisting of lava fountaining, lava flows, and spatter during January through September 2023 using information from daily reports, volcanic activity notices, and abundant photo, map, and video data from the US Geological Survey's (USGS) Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO).

Activity during January 2023. Small earthquake swarms were recorded on 2 January 2023; increased seismicity and changes in the pattern of deformation were noted on the morning of 5 January. At around 1500 both the rate of deformation and seismicity drastically increased, which suggested magma movement toward the surface. HVO raised the Volcano Alert Level (VAL) to Watch (the second highest level on a four-level scale) and the Aviation Color Code (ACC) to Orange (the second highest color on a four-color scale) at 1520.

Multiple lava fountains and lava effusions from vents in the central eastern portion of the Halema’uma’u crater began on 5 January around 0434; activity was confined to the eastern half of the crater and within the basin of the western half of the crater, which was the focus of the eruption in 2021-2022 (figure 525). Incandescence was visible in webcam images at 1634 on 5 January, prompting HVO to raise the VAL to Warning (the highest level on a four-level scale) and the ACC to Red (the highest color on a four-color scale). Lava fountains initially rose as high as 50 m above the vent at the onset of the eruption (figure 526) but then declined to a more consistent 5-6 m height in the proceeding days. By 1930 that same day, lava had covered most of the crater floor (an area of about 1,200,000 m2) and the lava lake had a depth of 10 m. A higher-elevation island that formed during the initial phase of the December 2020 eruption remained exposed, appearing darker in images, along with a ring of older lava around the lava lake that was active prior to December 2022. Overnight during 5-6 January the lava fountains continued to rise 5 m high, and the lava effusion rate had slowed.

On 6 January at 0815 HVO lowered the VAL to Watch and the ACC to Orange due to the declining effusion rates. Sulfur dioxide emission rates ranged from 3,000-12,500 tonnes per day (t/d), the highest value of which was recorded on 6 January. Lava continued to erupt from the vents during 6-8 January, although the footprint of the active area had shrunk; a similar progression has been commonly observed during the early stages of recent eruptions at Halema’uma’u. On 9 January HVO reported one dominant lava fountain rising 6-7 m high in the E half of the crater. Lava flows built up the margins of the lake, causing the lake to be perched. On 10 January the eastern lava lake had an area of approximately 120,000 m2 that increased to 250,000 m2 by 17 January. During 13-31 January several small overflows occurred along the margins of the E lake. A smaller area of lava was active within the basin in the W half of the crater that had been the focus of activity during 2021-2022. On 19 January just after 0200 a small ooze-out was observed on the crater’s W edge.

Activity during February 2023. Activity continued in the E part of Halema’uma’u crater, as well as in a smaller basin in the W part of the 2021-2022 lava lake (figure 527). The E lava lake contained a single lava fountain and frequent overflows. HVO reported that during the morning of 1 February the large E lava lake began to cool and crust over in the center of the lake; two smaller areas of lava were observed on the N and S sides by the afternoon. The dominant lava fountain located in the S part of the lava lake paused for roughly 45 minutes at 2315 and resumed by midnight, rising 1-2 m. At 0100 on 2 February lava from the S part was effusing across the entire E lava lake area, covering the crusted over portion in the center of the lake and continuing across the majority of the previously measured 250,000 m2 by 0400. A small lava pond near the E lake produced an overflow around 0716 on 2 February. On 3 February some lava crust began to form against the N and E levees, which defined the 250,000 m2 eastern lava lake. The small S lava fountain remained active, rising 1-6 m high during 3-9 February; around 0400 on 5 February occasional bursts doubled the height of the lava fountain.

A large breakout occurred overnight during 2100 on 4 February to 0900 on 5 February on the N part of the crater floor, equal to or slightly larger in size than the E lava lake. A second, smaller lava fountain appeared in the same area of the E lava lake between 0300 and 0700 on 5 February and was temporarily active. This large breakout continued until 7 February. A small, brief breakout was reported in the S of the E lava lake around midnight on 7 February. In the W lake, as well as the smaller lava pond in the central portion of the crater floor, contained several overflows during 7-10 February and intermittent fountaining. Activity at the S small lava pond and the small S lava fountain within the E lake declined during 9-10 February. The lava pond in the central portion of the crater floor had nearly continuous, expansive flows during 10-13 February; channels from the small central lava pond seemed to flow into the larger E lake. During 13-18 February a small lava fountain was observed in the small lava pond in the central portion of the crater floor. Continuous overflows persisted during this time.

Activity in the eastern and central lakes began to decline in the late afternoon of 17 February. By 18 February HVO reported that the lava effusions had significantly declined, and that the eastern and central lakes were no longer erupting. The W lake in the basin remained active but at a greatly reduced level that continued to decline. HVO reported that this decrease in activity is attributed to notable deflationary tilt that began early on the morning of 17 February and lasted until early 19 February. By 19 February the W lake was mostly crusted over although some weak lava flows remained, which continued through 28 February. The sulfur dioxide emission rates ranged 250-2,800 t/d, the highest value of which was recorded on 6 February.

Activity during March 2023. The summit eruption at Halema’uma’u crater continued at greatly reduced levels compared to the previous two months. The E and central vents stopped effusing lava, and the W lava lake remained active with weak lava flows; the lake was mostly crusted over, although slowly circulating lava intermittently overturned the crust. By 6 March the lava lake in the W basin had stopped because the entire surface was crusted over. The only apparent surface eruptive activity during 5-6 March was minor ooze-outs of lava onto the crater floor, which had stopped by 7 March. Several hornitos on the crater floor still glowed through 12 March according to overnight webcam images, but they did not erupt any lava. A small ooze-out of lava was observed just after 1830 in the W lava lake on 8 March, which diminished overnight. The sulfur dioxide emission rate ranged from 155-321 t/d on 21 March. The VAL was lowered to Advisory, and the ACC was lowered to Yellow (the second lowest on a four-color scale) on 23 March due to a pause in the eruption since 7 March.

Activity during April-May 2023. The eruption at Halema’uma’u crater was paused; no lava effusions were visible on the crater floor. Sulfur dioxide emission rates ranged from 75-185 t/d, the highest of which was measured on 22 April. During May and June summit seismicity was elevated compared to seismicity that preceded the activity during January.

Activity during June 2023. Earthquake activity and changes in the patterns of ground deformation beneath the summit began during the evening of 6 June. The data indicated magma movement toward the surface, prompting HVO to raise the VAL to Watch and the ACC to Orange. At about 0444 on 7 June incandescence in Halema’uma’u crater was visible in webcam images, indicating that a new eruption had begun. HVO raised the VAL to Warning and the ACC to Red (the highest color on a four-color scale). Lava flowed from fissures that had opened on the crater floor. Multiple minor lava fountains were active in the central E portion of the Halema’uma’u crater, and one vent opened on the W wall of the caldera (figure 528). The eruptive vent on the SW wall of the crater continued to effuse into the lava lake in the far SW part of the crater (figure 529). The largest lava fountain consistently rose 15 m high; during the early phase of the eruption, fountain bursts rose as high as 60 m. Lava flows inundated much of the crater floor and added about 6 m depth of new lava within a few hours, covering approximately 10,000 m2. By 0800 on 7 June lava filled the crater floor to a depth of about 10 m. During 0800-0900 the sulfur dioxide emission rate was about 65,000 t/d. Residents of Pahala (30 km downwind of the summit) reported minor deposits of fine, gritty ash and Pele’s hair. A small spatter cone had formed at the vent on the SW wall by midday, and lava from the cone was flowing into the active lava lake. Fountain heights had decreased from the onset of the eruption and were 4-9 m high by 1600, with occasional higher bursts. Inflation switched to deflation and summit earthquake activity greatly diminished shortly after the eruption onset.

At 0837 on 8 June HVO lowered the VAL to Watch and the ACC to Orange because the initial high effusion rates had declined, and no infrastructure was threatened. The surface of the lava lake had dropped by about 2 m, likely due to gas loss by the morning of 8 June. The drop left a wall of cooled lava around the margins of the crater floor. Lava fountain heights decreased during 8-9 June but continued to rise to 10 m high. Active lava and vents covered much of the W half of Halema’uma’u crater in a broad, horseshoe-shape around a central, uplifted area (figure 530). The preliminary average effusion rate for the first 24 hours of the eruption was about 150 cubic meters per second, though the estimate did not account for vesiculated lava and variations in crater floor topography. The effusion rate during the very earliest phases of the eruption appeared significantly higher than the previous three summit eruptions based on the rapid coverage of the entire crater floor. An active lava lake, also referred to as the “western lava lake” was centered within the uplifted area and was fed by a vent in the NE corner. Two small active lava lakes were located just SE from the W lava lake and in the E portion of the crater floor.

During 8-9 June the lava in the central lava lake had a thickness of approximately 1.5 m, based on measurements from a laser rangefinder. During 9-12 June the height of the lava fountains decreased to 9 m high. HVO reported that the previously active lava lake in the E part of the crater appeared stagnant during 10-11 June. The surface of the W lake rose approximately 1 m overnight during 11-12 June, likely due to the construction of a levee around it. Only a few small fountains were active during 12-13 June; the extent of the active lava had retreated so that all activity was concentrated in the SW and central parts of Halema’uma’u crater. Intermittent spattering from the vent on the SW wall was visible in overnight webcam images during 13-18 June. On the morning of 14 June a weak lava effusion originated from near the western eruptive vent, but by 15 June there were no signs of continued activity. HVO reported that other eruptive vents in the SW lava lake had stopped during this time, following several days of waning activity; lava filled the lake by about 0.5 m. Lava circulation continued in the central lake and no active lava was reported in the northern or eastern parts of the crater. Around 0800 on 15 June the top of the SW wall spatter cone collapsed, which was followed by renewed and constant spattering from the top vent and a change in activity from the base vent; several new lava flows effused from the top of the cone, as well as from the pre-existing tube-fed flow from its base. Accumulation of lava on the floor resulted in a drop of the central basin relative to the crater floor, allowing several overflows from the SW lava lake to cascade into the basin during the night of 15 June into the morning of 16 June.

Renewed lava fountaining was reported at the eruptive vent on the SW side of the crater during 16-19 June, which effused lava into the far SW part of the crater. This activity was described as vigorous during midday on 16 June; a group of observatory geologists estimated that the lava was consistently ejected at least 10 m high, with some spatter ejected even higher and farther. Deposits from the fountain further heightened and widened the spatter cone built around the original eruptive vent in the lower section of the crater wall. Multiple lava flows from the base of the cone were fed into the SW lava lake and onto the southwestern-most block from the 2018 collapse within Halema’uma’u on 17 June (figure 531); by 18 June they focused into a single flow feeding into the SW lava lake. On the morning of 19 June a second lava flow from the base of the eruptive cone advanced into the SW lava lake.

Around 1600 on 19 June there was a rapid decline in lava fountaining and effusion at the eruptive vent on the SW side of the crater; vent activity had been vigorous up to that point (figure 532). Circulation in the lava lake also slowed, and the lava lake surface dropped by several meters. Overnight webcam images showed some previously eruptive lava still flowing onto the crater floor, which continued until those flows began to cool. By 21 June no lava was erupting in Halema’uma’u crater. Overnight webcam images during 29-30 June showed some incandescence from previously erupted lava flows as they continued to cool. Seismicity in the crater declined to low levels. Sulfur dioxide emission rates ranged 160-21,000 t/d throughout the month, the highest measurement of which was recorded on 8 June. On 30 June the VAL was lowered to Advisory (the second level on a four-level scale) and the ACC was lowered to Yellow. Gradual inflation was detected at summit tiltmeters during 19-30 June.

Activity during July-August 2023. During July, the eruption paused; no lava was erupting in Halema’uma’u crater. Nighttime webcam images showed some incandescence from previously erupted lava as it continued to cool on the crater floor. During the week of 14 August HVO reported that the rate in seismicity increased, with 467 earthquakes of Mw 3.2 and smaller occurring. Sulfur dioxide emission rates remained low, ranging from 75-86 t/d, the highest of which was recorded on 10 and 15 August. On 15 August beginning at 0730 and lasting for several hours, a swarm of approximately 50 earthquakes were detected at a depth of 2-3 km below the surface and about 2 km long directly S of Halema’uma’u crater. HVO reported that this was likely due to magma movement in the S caldera region. During 0130-0500 and 1700-2100 on 21 August two small earthquake swarms of approximately 20 and 25 earthquakes, respectively, occurred at the same location and at similar depths. Another swarm of 50 earthquakes were recorded during 0430-0830 on 23 August. Elevated seismicity continued in the S area through the end of the month.

Activity during September 2023. Elevated seismicity persisted in the S summit with occasional small, brief seismic swarms. Sulfur dioxide measurements were relatively low and were 70 t/d on 8 September. About 150 earthquakes occurred during 9-10 September, and tiltmeter and Global Positioning System (GPS) data showed inflation in the S portion of the crater.

At 0252 on 10 September HVO raised the VAL to Watch and the ACC to Orange due to increased earthquake activity and changes in ground deformation that indicated magma moving toward the surface. At 1515 the summit eruption resumed in the E part of the caldera based on field reports and webcam images. Fissures opened on the crater floor and produced multiple minor lava fountains and flows (figure 533). The VAL and ACC were raised to Warning and Red, respectively. Gas-and-steam plumes rose from the fissures and drifted downwind. A line of eruptive vents stretched approximately 1.4 km from the E part of the crater into the E wall of the down dropped block by 1900. The lava fountains at the onset of the eruption had an estimated 50 m height, which later rose 20-25 m high. Lava erupted from fissures on the down dropped block and expanded W toward Halema’uma’u crater. Data from a laser rangefinder recorded about 2.5 m thick of new lava added to the W part of the crater. Sulfur dioxide emissions were elevated in the eruptive area during 1600-1500 on 10 September, measuring at least 100,000 t/d.

At 0810 on 11 September HVO lowered the VAL and ACC back to Watch and Orange due to the style of eruption and the fissure location had stabilized. The initial extremely high effusion rates had declined (but remained at high levels) and no infrastructure was threatened. An eruption plume, mainly comprised of sulfur dioxide and particulates, rose as high as 3 km altitude. Several lava fountains were active on the W side of the down dropped block during 11-15 September, while the easternmost vents on the down dropped block and the westernmost vents in the crater became inactive on 11 September (figure 534). The remaining vents spanned approximately 750 m and trended roughly E-W. The fed channelized lava effusions flowed N and W into Halema’uma’u. The E rim of the crater was buried by new lava flows; pahoehoe lava flows covered most of the crater floor except areas of higher elevation in the SW part of the crater. The W part of the crater filled about 5 m since the start of the eruption, according to data from a laser rangefinder during 11-12 September. Lava fountaining continued, rising as high as 15 m by the morning of 12 September. During the morning of 13 September active lava flows were moving on the N and E parts of the crater. The area N of the eruptive vents that had active lava on its surface became perched and was about 3 m higher than the surrounding ground surface. By the morning of 14 September active lava was flowing on the W part of the down dropped block and the NE parts of the crater. The distances of the active flows progressively decreased. Spatter had accumulated on the S (downwind) side of the vents, forming ramparts about 20 m high.

Vigorous spattering was restricted to the westernmost large spatter cone with fountains rising 10-15 m high. Minor spattering occurred within the cone to the E of the main cone, but HVO noted that the fountains remained mostly below the rim of the cone. Lava continued to effuse from these cones and likely from several others as well, traveled N and W, confined to the W part of the down-dropped block and the NE parts of Halema’uma’u. Numerous ooze-outs of lava were visible over other parts of the crater floor at night. Laser range-finder measurements taken of the W part of the crater during 14-15 September showed that lava filled the crater by 10 m since the start of the eruption. Sulfur dioxide emissions remained elevated after the onset of the eruption, ranging 20,000-190,000 t/d during the eruption activity, the highest of which occurred on 10 September.

Field crews observed the eruptive activity on 15 September; they reported a notable decrease or stop in activity at several vents. Webcam images showed little to no fountaining since 0700 on 16 September, though intermittent spattering continued from the westernmost large cone throughout the night of 15-16 September. Thermal images showed that lava continued to flow onto the crater floor. On 16 September HVO reported that the eruption stopped around 1200 and that there was no observable activity anywhere overnight or on the morning of 17 September. HVO field crews reported that active lava was no longer flowing onto Halema’uma’u crater floor and was restricted to a ponded area N of the vents on the down dropped block. They reported that spattering stopped around 1115 on 16 September. Nighttime webcam images showed some incandescence on the crater floor as lava continued to cool. Field observations supported by geophysical data showed that eruptive tremor in the summit region decreased over 15-16 September and returned to pre-eruption levels by 1700 on 16 September. Sulfur dioxide emissions were measured at a rate of 800 t/d on 16 September while the eruption was waning, and 200 t/d on 17 September, which were markedly lower compared to measurements taken the previous week of 20,000-190,000 t/d.

Geologic Background. Kilauea overlaps the E flank of the massive Mauna Loa shield volcano in the island of Hawaii. Eruptions are prominent in Polynesian legends; written documentation since 1820 records frequent summit and flank lava flow eruptions interspersed with periods of long-term lava lake activity at Halemaumau crater in the summit caldera until 1924. The 3 x 5 km caldera was formed in several stages about 1,500 years ago and during the 18th century; eruptions have also originated from the lengthy East and Southwest rift zones, which extend to the ocean in both directions. About 90% of the surface of the basaltic shield volcano is formed of lava flows less than about 1,100 years old; 70% of the surface is younger than 600 years. The long-term eruption from the East rift zone between 1983 and 2018 produced lava flows covering more than 100 km2, destroyed hundreds of houses, and added new coastline.

Information Contacts: Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO), U.S. Geological Survey, PO Box 51, Hawai'i National Park, HI 96718, USA (URL: http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/).

Tinakula (Solomon Islands) — December 2023  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Tinakula

Solomon Islands

10.386°S, 165.804°E; summit elev. 796 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Continued lava flows and thermal activity during June through November 2023

Tinakula is a remote 3.5 km-wide island in the Solomon Islands, located 640 km ESE of the capital, Honiara. The current eruption period began in December 2018 and has more recently been characterized by intermittent lava flows and thermal activity (BGVN 48:06). This report covers similar activity during June through November 2023 using satellite data.

During clear weather days (20 July, 23 September, 23 October, and 12 November), infrared satellite imagery showed lava flows that mainly affected the W side of the island and were sometimes accompanied by gas-and-steam emissions (figure 54). The flow appeared more intense during July and September compared to October and November. According to the MODVOLC thermal alerts, there were a total of eight anomalies detected on 19 and 21 July, 28 and 30 October, and 16 November. Infrared MODIS satellite data processed by MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) detected a small cluster of thermal activity occurring during late July, followed by two anomalies during August, two during September, five during October, and five during November (figure 55).

Geologic Background. The small 3.5-km-wide island of Tinakula is the exposed summit of a massive stratovolcano at the NW end of the Santa Cruz islands. It has a breached summit crater that extends from the summit to below sea level. Landslides enlarged this scarp in 1965, creating an embayment on the NW coast. The Mendana cone is located on the SE side. The dominantly andesitic volcano has frequently been observed in eruption since the era of Spanish exploration began in 1595. In about 1840, an explosive eruption apparently produced pyroclastic flows that swept all sides of the island, killing its inhabitants. Recorded eruptions have frequently originated from a cone constructed within the large breached crater. These have left the upper flanks and the steep apron of lava flows and volcaniclastic debris within the breach unvegetated.

Information Contacts: MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Fuego (Guatemala) — December 2023  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Fuego

Guatemala

14.4748°N, 90.8806°W; summit elev. 3799 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Daily explosions, gas-and-ash plumes, and block avalanches during August-November 2023

Fuego is one of three large stratovolcanoes overlooking the city of Antigua, Guatemala. It has been erupting since January 2002, with observed eruptions dating back to 1531 CE. Typical activity is characterized by ashfall, pyroclastic flows, lava flows, and lahars. Frequent explosions with ash emissions, block avalanches, and lava flows have been reported since 2018. More recently, activity has been characterized by multiple explosions and ash plumes each day, ashfall, block avalanches, and pyroclastic flows (BGVN 48:09). This report describes similar activity of explosions, gas-and-ash plumes, and block avalanches during August through November 2023 based on daily reports from the Instituto Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanología, Meteorología e Hidrologia (INSIVUMEH) and various satellite data.

Multiple explosions each day were reported during August through November 2023 that produced ash plumes that rose to 4.9 km altitude and drifted as far as 30 km in different directions. The explosions also caused rumbling sounds of varying intensities, with shock waves that vibrated the roofs and windows of homes near the volcano. Incandescent pulses of material rose as high as 350 m above the crater, accompanied by block avalanches that descended multiple drainages. Light ashfall was often reported in nearby communities (table 29). MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) analysis of MODIS satellite data showed intermittent low-to-moderate power thermal activity during the reporting period (figure 175). A total of seven MODVOLC thermal alerts were issued on 11 August, 1, 13, and 23 September, and 10, 17, and 18 November. On clear weather days thermal anomalies were also visible in infrared satellite imagery in the summit crater (figure 176).

Table 29. Activity at Fuego during August through November 2023 included multiple explosions every hour. Ash emissions rose as high as 4.9 km altitude and drifted in multiple directions as far as 30 km, causing ashfall in many communities around the volcano. Data from daily INSIVUMEH reports.

| Month |

Explosions per hour |

Maximum ash plume altitude (km) |

Ash plume direction and distance (km) |

Drainages affected by block avalanches |

Communities reporting ashfall |

| Aug 2023 |

1-11 |

4.8 |

W, NW, SW, N, NE, and E 8-30 km |

Ceniza, Santa Teresa, Seca, Taniluyá, Las Lajas, El Jute, Trinidad, and Honda |

Panimaché, Morelia, Santa Sofía, Yepocapa, Finca Palo Verde, Sangre de Cristo, Acatenango, Aldeas, El Porvenir, La Reunión, San Miguel Dueñas, Cuidad Vieja, Antigua, Quisaché, and El Sendero |

| Sep 2023 |

3-11 |

4.8 |

SW, W, NW, S, and SE 10-30 km |

Seca, Taniluyá, Ceniza, Las Lajas, Honda, Santa Teresa, Trinidad, and El Jute |

Panimaché I and II, Morelia, Palo Verde, Sangre de Cristo, Yepocapa, El Porvenir, Aldeas, Santa Sofía, Montellano, El Socorro, La Rochela, La Asunción, San Andrés Osuna, Guadalupe, and La Trinidad |

| Oct 2023 |

2-10 |

4.9 |

W, SW, S, NW, N, NE, and SE 10-30 km |

Ceniza, Santa Teresa, Taniluyá, Trinidad, Seca, El Jute, Las Lajas, and Honda |

Aldeas, Panimaché I and II, Morelia, Santa Sofía, El Porvenir, Sangre de Cristo, Yepocapa, Yucales, Palo Verde, Acatenango, Patzicía, San Miguel Dueñas, Alotenango, La Soledad, El Campamento, La Rochela, Las Palmas, and Quisaché |

| Nov 2023 |

1-10 |

4.8 |

W, SW, S, E, SE, NW, and N 10-30 km |

Seca, Taniluyá, Ceniza, Las Lajas, EL Jute, Honda, Santa Teresa, and Trinidad |

Panimaché I and II, Morelia, Yepocapa, Santa Sofía, Aldeas, Sangre de Cristo, Palo Verde, El Porvenir, Yucales, La Rochela, San Andrés Osuna, Ceilán, Quisaché, Acatenango, and La Soledad |

Activity during August consisted of 1-11 explosions each day, which generated ash plumes that rose to 4-4.8 km altitude and drifted 8-30 km W, NW, SW, N, NE, and E. Fine ashfall was reported in Panimaché I and II (8 km SW), Morelia (9 km SW), Santa Sofía (12 km SW), Yepocapa (8 km NW), Finca Palo Verde (10 km WSW), Sangre de Cristo (8 km WSW), Acatenango (8 km E), Aldeas, El Porvenir (11 km SW), La Reunión (7 km SE), San Miguel Dueñas (10 km NE), Ciudad Vieja (13.5 km NE), Antigua (18 km NE), Quisaché (8 km NW), and El Sendero. The explosions sometimes ejected incandescent material 50-250 m above the crater and generated weak-to-moderate block avalanches that descended the Santa Teresa (W), Seca (W), Taniluyá (SW), Ceniza (SSW), Las Lajas (SE), El Jute (ESE), Trinidad (S), and Honda (E) drainages. Lahars were reported in the Ceniza drainage on 8-9, 16, 26-27, and 29 August, carrying fine and hot volcanic material, branches, tree trunks, and blocks measured 30 cm up to 1.5 m in diameter. Similar lahars affected the Las Lajas, El Jute, Seca, and El Mineral (W) drainages on 27 August.

Daily explosions ranged from 3-11 during September, which produced ash plumes that rose to 4-4.8 km altitude and drifted 10-30 km SW, W, NW, S, and SE. The explosions were accompanied by block avalanches that affected the Seca, Taniluyá, Ceniza, Las Lajas, Honda, Santa Teresa, Trinidad, and El Jute drainages and occasional incandescent ejecta rose 50-300 m above the crater. Fine ashfall was reported in Panimaché I and II, Morelia, Palo Verde, Sangre de Cristo, Yepocapa, El Porvenir, Aldeas, Santa Sofía, Montellano, El Socorro, La Rochela (8 km SSW), La Asunción (12 km SW), San Andrés Osuna (11 km SSW), Guadalupe, La Trinidad (S). Lahars triggered by rainfall were detected in the Ceniza drainage on 3-4, 8, 13-14, 17, 20-21, 24, 26, 29-30 September, which carried fine and hot volcanic material, branches, tree trunks, and blocks measuring 30 cm to 3 m in diameter. Similar lahars were also detected in the Seca, El Mineral, Las Lajas, and El Jute drainages on 27 September.

There were 2-10 explosions recorded each day during October, which produced ash plumes that rose to 4-4.9 km altitude and drifted 10-30 km W, SW, S, NW, N, NE, and SE. Incandescent pulses of material rose 50-350 m above the crater. Many of the explosions generated avalanches that descended the Ceniza, Santa Teresa, Taniluyá, Trinidad, Seca, El Jute, Las Lajas, and Honda drainages. Ashfall was reported in Aldeas, Panimaché I and II, Morelia, Santa Sofía, El Porvenir, Sangre de Cristo, Yepocapa, Yucales, Palo Verde, Acatenango, Patzicía, Alotenango, La Soledad (11 km N), El Campamento, La Rochela, Las Palmas, and Quisaché. Lahars continued to be observed on 2-5, 7, 9, 11, and 21-22 October, carrying fine and hot volcanic material, branches, tree trunks, and blocks measuring 30 cm to 3 m in diameter. Similar lahars were also reported in the Seca and Las Lajas drainage on 2 October and in the Las Lajas drainage on 4 October. On 4 October lahars overflowed the Ceniza drainage toward the Zarco and Mazate drainages, which flow from Las Palmas toward the center of Siquinalá, resulting from intense rainfall and the large volume of pyroclastic material in the upper part of the drainage. On 9 October a lahar was reported in the Seca and Las Lajas drainages, and lahars in the Las Lajas and El Jute drainages were reported on 11 October. A lahar on 22 October was observed in the Seca drainage, which interrupted transportation between San Pedro Yepocapa and the communities in Santa Sofía, Morelia, and Panimaché.

During November, 1-10 daily explosions were recorded, sometimes accompanied by avalanches, rumbling sounds, and shock waves. Gas-and-ash plumes rose 4.5-4.8 km altitude and extended 10-30 km W, SW, S, E, SE, NW, and N. Incandescent pulses of material rose 50-200 m above the crater. Fine ashfall was reported in Panimaché I and II, Morelia, Yepocapa, El Porvenir, Palo Verde, Santa Sofía, Aldeas, Sangre de Cristo, Yucales, La Rochela, San Andrés Osuna, Ceilán (9 km S), Quisaché, Acatenango, La Soledad. Avalanches of material descended the Seca, Taniluyá, Ceniza, Las Lajas, El Jute, Honda, Santa Teresa, and Trinidad drainages.

Geologic Background. Volcán Fuego, one of Central America's most active volcanoes, is also one of three large stratovolcanoes overlooking Guatemala's former capital, Antigua. The scarp of an older edifice, Meseta, lies between Fuego and Acatenango to the north. Construction of Meseta dates back to about 230,000 years and continued until the late Pleistocene or early Holocene. Collapse of Meseta may have produced the massive Escuintla debris-avalanche deposit, which extends about 50 km onto the Pacific coastal plain. Growth of the modern Fuego volcano followed, continuing the southward migration of volcanism that began at the mostly andesitic Acatenango. Eruptions at Fuego have become more mafic with time, and most historical activity has produced basaltic rocks. Frequent vigorous eruptions have been recorded since the onset of the Spanish era in 1524, and have produced major ashfalls, along with occasional pyroclastic flows and lava flows.

Information Contacts: Instituto Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanologia, Meteorologia e Hydrologia (INSIVUMEH), Unit of Volcanology, Geologic Department of Investigation and Services, 7a Av. 14-57, Zona 13, Guatemala City, Guatemala (URL: http://www.insivumeh.gob.gt/ ); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Santa Maria (Guatemala) — December 2023  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Santa Maria

Guatemala

14.757°N, 91.552°W; summit elev. 3745 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Continuing lava effusion, explosions, ash plumes, and pyroclastic flows during August-November 2023

The Santiaguito lava dome complex of Guatemala’s Santa María volcano has been actively erupting since 1922. The lava dome complex lies within a large crater on the SW flank of Santa María that was formed during the 1902 eruption. Ash explosions, pyroclastic flows, and lava flows have emerged from Caliente, the youngest of the four vents in the complex for more than 40 years. A lava dome that appeared within Caliente’s summit crater in October 2016 has continued to grow, producing frequent block avalanches down the flanks. More recently, activity has been characterized by frequent explosions, lava flows, ash plumes, and pyroclastic flows (BGVN 48:09). This report covers activity during August through November 2023 based on information from Guatemala's INSIVUMEH (Instituto Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanologia, Meterologia e Hidrologia) and various satellite data.