In repose; background conditions and hazards

This is the first Bulletin report for Mauna Kea, the tallest volcano on the Island of Hawai`i (figures 1, 2, and 3). Although the most recent eruption occurred ~4,500 years ago, this volcano has the potential to reawaken. This report presents early observations by Western explorers; discussions from Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) scientists focusing on the potential for future eruptions; seismicity during 2000-2013; and a recent report by HVO scientists highlighting drastic changes at an alpine lake, Lake Waiau.

Eruptive style and activity status. Mauna Kea is presently considered a volcano exhibiting quiescence that has, according to the known geologic record, an extensive history of lapsed activity. Between 6,000 and 4,000 years ago, eruptions occurred at at least seven separate vents. The record indicates that compared with Mauna Loa, which erupted every few years to few tens of years, and Hualalai, which erupted every few hundred years, Mauna Kea has exhibited long breaks in activity (USGS, 2002).

Based on the occurrence of 12 eruptions within a 10,000 year period, Mauna Kea's recurrence interval is ~1,000 years (Geohazards Consultants International, Inc., 2000). According to the Mauna Kea Science Reserve Master Plan released by the Geohazards Consultants International, Inc. in March 2000:

"Mauna Kea's post-glacial eruptions have been episodic rather than periodic, however, with a particular concentration of eruptive activity between 4,400-5,600 years ago. The 1,000 year recurrence interval of the past 10,000 years does not thus indicate that an eruption is 'overdue', but does reinforce the likelihood that eruptions will occur sporadically in the future."

This pattern of activity might also imply that the next eruption of Mauna Kea could be followed by others at much shorter intervals, representing a potential clustering of events in the given time interval (Jim Kauahikaua, personal communication, 30 May 2014).

Mauna Kea's most recent eruption occurred ~4,500 years ago, generating both lava flows and cinder cones. This activity is considered characteristic of a volcanic system that had evolved past the shield-building stage to the post-shield stage (Hoover and Fodor, 1997). The above-stated age determinations were made based on radiocarbon dating of charcoal collected within the Humu`ula soil (Porter, 1971; Wolfe and others, 1997); this soil lies directly beneath the S flank lava flows of Pu`ukole and Pu`u Loa Loa (figure 4).

The designations of shield-building and post-shield stages come from a system of structural development that represents the current understanding of Hawaiian volcanism. Significant cinder cone eruptions are a hallmark of the post-shield stage as well as: "(1) the absence of a summit caldera and elongated fissure vents that radiate across its summit; (2) steeper and more irregular topography (for example, the upper flanks of Mauna Kea are twice as steep as those of Mauna Loa; [figure 5]); and (3) different chemical compositions of the lava" (Clague and Dalrymple, 1987; USGS, 2002).

Gravity model. Investigations by Kauahikaua and others (2000) determined a three-dimensional gravity model for the Island of Hawai`i distinguished the five volcanic centers comprising the island: Kohala, Mauna Kea, Hualalai, Mauna Loa, and Kīlauea (figure 6). The base data for that map came from more than 3,300 gravity measurements made above sea level. Positive gravity anomalies define gravitationally dense zones caused by intrusions and cumulates beneath the summit and known rift zones of each of the five volcanoes composing the island. Figure 6 maps the 3-dimensional structure as modeled from the gravity data and expresses the gravity anomalies in terms of elevation from the overlying ground surface.

"Mauna Kea has an elliptical-shaped core, slightly elongated east-west, with a broad, linear feature trending southeast. This linear feature may be a buried rift zone of Mauna Kea, although no surface expressions of those rift zones have been mapped (Kauahikaua and others, 2000)."

The submarine feature known as the Hilo Ridge was also included in the density study with data contributed by GLORIA (a side-scan sonar) as well as satellites ERS-1, Geosat, and Seasat. Prior to this investigation, the Hilo Ridge had been attributed to Mauna Kea as its possible rift zone; however, the authors determined a stronger connection with Kohala due to multiple factors including the strongly NW-trending linear zone that extends ~80 km from the modelled core of Kohala.

Early European observations. An early survey of Hawai`i was conducted by Archibald Menzies, a botanist who accompanied Captain George Vancouver during the cruises of 1792-1794. Menzies successfully ascended Mauna Loa in February 1794 (a team from Captain Cook's crew had unsuccessfully attempted the summit in 1779; see figure 7). Menzies estimated the heights of Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea to within 31 m of the currently accepted value, "a remarkable surveying feat for that time" (Wright and others, 1992b).

The first petrologist to study Mauna Kea, R.A. Daly, determined not only that Mauna Kea's upper flanks were dominated by lava flows more rich in silica (he called them "andesite" although current classifications label them "hawaiite"), but also that the edifice had been modified by glaciers (Wolfe and others, 1997; Daly, 1911). Stearns and Macdonald (1946) and Washington (1923) expanded the knowledge base of Mauna Kea's geochemistry, and Gregory and Wentworth (1937) established that the glacial features from the most recent glacial episode (40,000 to 13,000 years ago) were interspersed with primary volcanic material. Wolfe and others (1997) determined that "eruptive activity of Mauna Kea was partly contemporaneous with that at Kohala, Hualalai, and Mauna Loa, and the volcano boundaries are undoubtedly complex."

HVO Volcano Watch article highlights a Mauna Kea forecast. The potential for a future eruption from Mauna Kea was addressed in a Volcano Watch article posted in June 2000 by then Scientist-in-Charge, Don Swanson, from the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) (Swanson, 2000ab). The article addresses not only eruption frequency but also trends in eruption style, the potential response of the telescope installation at Mauna Kea's summit, and a general forecast for a likely scenario in the future.

"The next eruption of Mauna Kea."

"Mauna Kea's peaceful appearance is misleading. The volcano is not dead. It erupted many times between 60,000 and 4,000 years ago, and some periods of quiet during that time apparently lasted longer than 4,000 years. Given that record, future eruptions seem almost certain.

"Before the next one, we should have ample warning provided by our current seismic and geodetic monitoring systems. A number of earthquakes occur beneath Mauna Kea each year, and you can bet that we pay close attention to them. However, they all appear to be associated with tectonic faulting rather than movement of magma.

"The telescopes on top of the volcano may be the first to indicate that something is amiss. The coordinates used for tracking their observations will begin to drift unexpectedly as the volcano is swelling. In a sense, the telescopes will serve as very expensive tiltmeters.

"We cannot now say when the next eruption will take place, except that it is unlikely to be in the next several months, given the current lack of any precursory signs. Whether the timing is years, centuries, or millennia is entirely unclear.

"But we can say something about the probable nature of the next eruption, because we know what the most recent ones were like, thanks to recently published research by Ed Wolfe [see Wolfe and others, 1997], former staff member of HVO, and colleagues.

"The next eruption could take place anywhere on the upper flanks of the volcano. As Mauna Kea evolved from its early shield stage (equivalent to Kīlauea and Mauna Loa today) to its present postshield stage, the volcano lost its rift zones. Consequently, the postshield eruptions are not concentrated along narrow zones but instead are scattered across the mountain. [See figure 6.]

"For example, the most recent eruptive period, 6,000-4,000 years ago, involved eight vents on the south flank of the volcano between Kala`i`eha cone (near Humu`ula) and Pu`ukole (east of Hale Pohaku). During this same period, eruptions took place on the northeast flank at Pu`u Lehu and Pu`u Kanakaleonui. Lava from Pu`u Kanakaleonui flowed more than 20 km (12 miles) northeastward, entering the sea to form Laupahoehoe Point.

"The next eruption will likely produce a lava flow, because each eruption in the past 60,000 years has done so. The longest flows will reach 15-25 km (9-15 miles) downslope. Most of each flow will be `a`a, but pahoehoe may form near vents.

"A prominent cinder cone will probably be constructed at each vent. The cinder cones responsible for the "bumpy" appearance of Mauna Kea's surface formed during the 60,000-4,000-year interval. The cones mentioned by name above, and several others, were built during the latest eruptive period 6,000-4,000 years ago. The next eruption will likely produce a similar cone.

"Cinder cones form at vents that are point sources, not elongate fissures. All activity is concentrated at one place, so that fountaining and spattering build a high cone rather than a long rampart. Past eruptions-and hence future ones--probably lasted months to several years, providing enough time to construct a substantial cone. Those eruptions spread voluminous ash deposits far beyond the cinder cones themselves, and the next eruption will probably do so, too.

"Possibly, however, there will not be enough spattering to build a lasting cone. Such an eruption happened about 1 km (0.6 miles) southeast of Hale Pohaku, when a vent put out a moderate volume of lava without building a spatter or cinder cone.

"The next eruption of Mauna Kea is unlikely to occur in our lifetimes, but it could. There is no reason to fear such an eruption. It would not threaten human life, provided due care were taken, though it could prove devastating to property and infrastructure, particularly if a lava flow traveled to the Hamakua coast or the Waimea area."

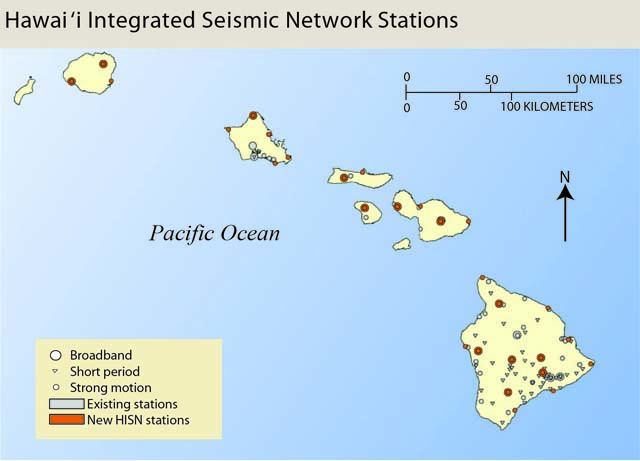

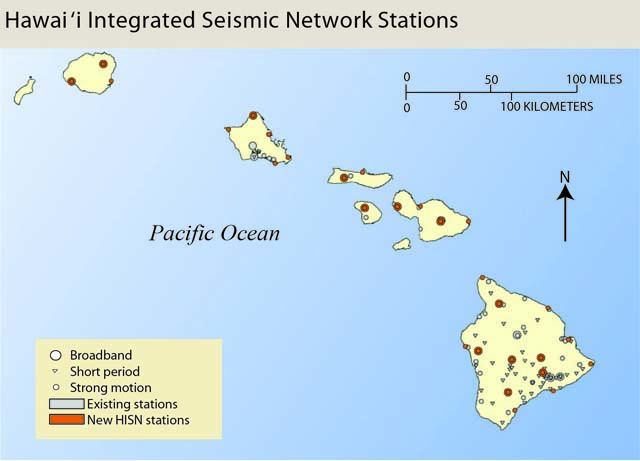

Mauna Kea's seismicity. HVO has monitored and maintained the record of seismicity for the entire region of Hawai`i. The seismicity detected beneath Mauna Kea has been characterized as "infrequent and sparse." Notable seismicity occurred in 1994, 2001, and 2011, when earthquakes were large enough to be felt by the general public. Island-wide instrumentation allowed excellent location data for the local seismicity (figure 8).

|

Figure 8. The seismic network that monitors Mauna Kea and the other volcanoes of Hawai`i spans six islands. This map appeared in the USGS Fact Sheet released in 2011. |

HVO reported that, several times each year, earthquakes from Mauna Kea cause shaking that is noted by local populations - especially the operators of the Mauna Kea astronomical observatory, who rely on stable instrumentation in order to make precise observations. Reports of felt earthquakes from Mauna Kea correlated with magnitude 2.1-4.9 earthquakes during 1973-2012.

Elevated seismicity during October-December 2011 resulted in 30 felt earthquakes. Approximately 570 people reported the M 4.5 earthquake that occurred on 20 October 2011 and also 10 of the aftershocks that followed (figure 9). HVO reported that, like many of Mauna Kea's earthquakes, these earthquakes were "most likely caused by structural adjustments within the Earth's crust due to the heavy load of Mauna Kea." With an estimated volume of >30,000 km3, Mauna Kea rises ~10,000 m above the seafloor, causing stress to accumulate from the mass of the volcano (Lockwood and Hazlett, 2010).

Earthquake swarms at Mauna Kea. HVO reported that earthquake swarms occasionally occur at Mauna Kea. On 23 February 2001, a swarm of ~15 events was detected within a 21-hour period. These earthquakes were mainly located ~15 km S of Pa`auilo (~3 km NW of Kuka`iau, figure 10), at a depth of 8-11 km.

Lake Waiau recedes. The cinder cone Pu`uwaiau, located within 2 km of the summit, has contained a freshwater lake that was considered permanent by Wolfe and others (1997) (figures 11 and 12). Lake Waiau has likely persisted due to the once-glassy cinders and bombs that have weathered to smectite with zeolites within the void spaces. These alteration products may serve as a weak cement between the pyroclasts and reduce the permeability of the cinder cone's base. Sporadic winter storms have provided most, if not all, of the water captured in this considerably arid region (Patrick and Delparte, 2014). Contributions from permafrost were also proposed by Woodcock (1980), but the presence of permafrost has not been confirmed near Lake Waiau.

Patrick and Delparte (2014) reported that the lake size before 2010 was 5,000-7,000 m2 with a depth of ~3 m, but recently, the size has been decreasing rapidly. In the recent past, the lake was known to overflow through the Pohakuloa Gulch when water levels exceeded the rim (as recently as February 2002) (Ehlmann and others, 2005).

Researchers have determined that Lake Waiau is sensitive to precipitation levels (Woodcock, 1980) and that ongoing drought conditions could be driving the lake's change (Patrick and Delparte, 2014). Based on the National Drought Mitigation Center's data, since 2008, and notably in March 2010, precipitation has been sparse at the summit of Mauna Kea.

In December 2013, scientists visited the lake and observed an unprecedented sight (figure 13). Lake Waiau measured a mere 115 m2 and was roughly 10-20 cm deep (Patrick and Delparte, 2014). While the lake size was known to fluctuate over time, this dramatic reduction has caused concern, given the possibility of losing a specialized ecosystem as well as a prominent feature of Hawaiian ethnogeography. Mauna Kea's summit is considered "one of the most sacred spots in the Hawaiian Islands. Archaeological sites near the summit attest to its prolonged spiritual importance...(Patrick and Delparte, 2014)."

USGS scientists at HVO as well as collaborators, including Idaho State University, continued to study the conditions at Lake Waiau after the significant survey was conducted in December 2013. As of May 2014, strong winter rains had partially restored the lake, providing stronger evidence that the multi-year shrinkage was due to the ongoing drought as opposed to changes in the volcanic system.

A note regarding the name Mauna Kea. The popular translation of the Hawaiian name Mauna Kea is frequently "White Mountain," however, significant discussions have focused on the source of the name. There has been growing consensus that Mauna Kea is a shortened form of Mauna a Wakea, which refers to the sky father Wakea.

According to testaments presented in the Final Environmental Impact Statement of the Federal Highway Administration Project No. A-AD-6(1) which included potential cultural impacts on the island by expanding State Routes 190 and 200, "The mountain is the sacred child of Wakea, and it is the source for the land. The mountains and land were genealogically connected to native Hawaiians through the original ancestor, Wakea [sky father] and Papa [earth mother]."

Ethnographic research conducted prior to 1999 and released in the impact statement concluded that the summit area of Mauna Kea was eligible for the National Register of Historic Places due to traditional cultural property.

A note regarding Hawaiian names and nomenclature. As previously noted in other Bulletin reports, according to Runyon (2006), "The U.S. Board on Geographic Names (BGN) is responsible for establishing and maintaining uniform geographical name usage throughout all departments and agencies of the United States government. As such, the Board collects and promulgates every name that is considered official for Federal use. The official vehicle for promulgating these names and their locative attributes is the Geographic Names Information System (GNIS).

"Until the 1990's, it was also Federal policy to omit most diacritics and writing marks from placenames on Federal maps and documents. The few exceptions included the Spanish tilde and the French accent marks, but otherwise the special characters found in indigenous names were always dropped. In more recent years, however, the BGN has amended its policy to permit the inclusion of such marks, thus more accurately reflecting the true representation of the native language. An example of this has been the addition of the glottal stop (okina) and macron (kahako) to placenames of Hawaiian origin, which prior to 1995 had always been omitted. The BGN staff, under the direction and guidance of the Hawaii State Geographic Names Authority, has been restoring systemically these marks to each Hawaiian name listed in GNIS."

GVP will strive to conform to GNIS nomenclature. It remains a technological challenge, but a goal.

References: Clague, D.A., and Dalrymple, G.B., 1987, The Hawaiian-Emperor volcanic chain. Part I. Geologic evolution, chap. 1 of Decker, R.W, Wright, T.L., and Stauffer, PH., eds., Volcanism in Hawaii: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1350, v. 1, p. 5-54.

Daly, R.A., 1911, Magmatic differentiation in Hawaii: Journal of Geology, v. 19, no. 4, p. 289-316.

Federal Highway Administration, 1999, Final Environmental Impact Statement Part 1: Hawaii State Route 200, Mamalahoa Highway (SR 190) to Milepost 6 Saddle Road, County of Hawai`i, State of Hawai`i, FHWA Project No. A-AD-6(1).

Ehlmann, B.L., Arvidson, R.E., Jolliff, B.L., Johnson, S.S., Ebel, B., Lovenduski, N., Morris, J.D., Beyers, J.A., Snider, N.O., and Criss, R.E., 2005. Hydrologic and isotopic modeling of Alpine Lake Waiau, Mauna Kea, Hawai`i. University of Hawaii Press, p. 1-15.

Fitzpatrick, G.L, 1986. The early mapping of Hawaii. Honolulu: Editions Limited, vol. 1, 160 pp.

Geohazards Consultants International, Inc., Mauna Kea Science Reserve Master Plan, Volcano, HI, March 2000, 22 p.

Gregory, H.E., and Wentworth, C.K., 1937, General features and glacial geology of Mauna Kea, Hawaii: Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 48, no. 12, p. 1719-1742.

Holt, Rinehart, and Winston (2006), Hawaii. Retrieved from http://go.hrw.com/atlas/norm_htm/hawaii.htm.

Hoover, S.R. and Fodor, R.V., 1997, Magma-reservoir crystallization processes: small-scale dikes in cumulate gabbros, Mauna Kea Volcano, Hawaii, Bulletin of Volcanology, 59, p. 186-197.

Kauahikaua, J., Hildenbrand, T., & Webring, M., 2000. Deep magmatic structures of Hawaiian volcanoes, imaged by three-dimensional gravity models. Geology, 28, 10, p. 883.

Lockwood, J.P., and Hazlett, R.W., 2010. Volcanoes: Global Perspectives, Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, NJ, ix, 539 p.

Okubo, P.G. and Nakata, J.S., 2011, Earthquakes in Hawai`i-An Underappreciated but Serious Hazard, Fact Sheet 2011-3013, USGS Fact Sheet, September 2011. (http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2011/3013/)

Patrick, M. R. and Delparte, D., 2014, Tracking Dramatic Changes at Hawaii's Only Alpine Lake: EOS (Transactions, American Geophysical Union), Vol. 95, No. 14, p. 117-118.

Porter, S.C., 1971, Holocene Eruptions of Mauna Kea Volcano, Hawaii, Science, Vol. 172 no. 3981 p. 375-377.

Stearns, H.T., and Macdonald, G.A., 1946, Geology and ground-water resources of the Island of Hawaii: Hawaii Division of Hydrography Bulletin 9, 363 p.

Swanson, D.A., (June 2000a). The next eruption of Mauna Kea. Volcano Watch. Retrieved from http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanowatch/archive/2000/00_06_01.html.

Swanson, D.A., 2000b, Don't be fooled by seemingly peaceful Mauna Kea Volcano--it could erupt again: Hawaii Tribune-Herald, June 4, p. 2.

USGS-HVO (May 2002). Mauna Kea Hawai`i's Tallest Volcano. Other Volcanoes. Retrieved from http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanoes/maunakea/.

Washington, H.S., 1923, Petrology of the Hawaiian Islands; I, Kohala and Mauna Kea, Hawaii: American Journal of Science, ser. 5, v. 5, no. 30, p. 465-502.

Wolfe, E.W., Wise, W.S., and Dalrymple, G.B., 1997, The geology and petrology of Mauna Kea volcano, Hawaii: a study of postshield volcanism. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1557, Washington, D.C.: U.S. G.P.O.

Woodcock, A., 1980. Hawaiian alpine lake level, rainfall trends, and spring flow, Pacific Science, 34, p. 195–209.

Wright, T.L., Chu, J.Y., Esposo, J., Heliker, C., Hodge, J., Lockwood, J.P., and Vogt, S.M., 1992a, Map showing lava-flow hazard zones, island of Hawaii: U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Field Studies Map MF-2193, scale 1:250,000.

Wright, T.L., Takahashi, T.J., and Griggs, J.D., 1992b, Hawai`i Volcano Watch: A Pictorial History, 1779-1991, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 162 p.

Information Contacts: Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO), U.S. Geological Survey, PO Box 51, Hawai`i National Park, HI 96718, USA (URL: https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/observatories/hvo/); Richard Wainscoat, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Institute for Astronomy (URL: http://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/, http://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/images/aerial-tour-95/); Scott Rowland, University of Hawaii at Manoa, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (URL: http://www.soest.hawaii.edu/); and Hawaii News Now (URL: http://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/).

The Global Volcanism Program has no Weekly Reports available for Mauna Kea.

Reports are organized chronologically and indexed below by Month/Year (Publication Volume:Number), and include a one-line summary. Click on the index link or scroll down to read the reports.

In repose; background conditions and hazards

This is the first Bulletin report for Mauna Kea, the tallest volcano on the Island of Hawai`i (figures 1, 2, and 3). Although the most recent eruption occurred ~4,500 years ago, this volcano has the potential to reawaken. This report presents early observations by Western explorers; discussions from Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) scientists focusing on the potential for future eruptions; seismicity during 2000-2013; and a recent report by HVO scientists highlighting drastic changes at an alpine lake, Lake Waiau.

Eruptive style and activity status. Mauna Kea is presently considered a volcano exhibiting quiescence that has, according to the known geologic record, an extensive history of lapsed activity. Between 6,000 and 4,000 years ago, eruptions occurred at at least seven separate vents. The record indicates that compared with Mauna Loa, which erupted every few years to few tens of years, and Hualalai, which erupted every few hundred years, Mauna Kea has exhibited long breaks in activity (USGS, 2002).

Based on the occurrence of 12 eruptions within a 10,000 year period, Mauna Kea's recurrence interval is ~1,000 years (Geohazards Consultants International, Inc., 2000). According to the Mauna Kea Science Reserve Master Plan released by the Geohazards Consultants International, Inc. in March 2000:

"Mauna Kea's post-glacial eruptions have been episodic rather than periodic, however, with a particular concentration of eruptive activity between 4,400-5,600 years ago. The 1,000 year recurrence interval of the past 10,000 years does not thus indicate that an eruption is 'overdue', but does reinforce the likelihood that eruptions will occur sporadically in the future."

This pattern of activity might also imply that the next eruption of Mauna Kea could be followed by others at much shorter intervals, representing a potential clustering of events in the given time interval (Jim Kauahikaua, personal communication, 30 May 2014).

Mauna Kea's most recent eruption occurred ~4,500 years ago, generating both lava flows and cinder cones. This activity is considered characteristic of a volcanic system that had evolved past the shield-building stage to the post-shield stage (Hoover and Fodor, 1997). The above-stated age determinations were made based on radiocarbon dating of charcoal collected within the Humu`ula soil (Porter, 1971; Wolfe and others, 1997); this soil lies directly beneath the S flank lava flows of Pu`ukole and Pu`u Loa Loa (figure 4).

The designations of shield-building and post-shield stages come from a system of structural development that represents the current understanding of Hawaiian volcanism. Significant cinder cone eruptions are a hallmark of the post-shield stage as well as: "(1) the absence of a summit caldera and elongated fissure vents that radiate across its summit; (2) steeper and more irregular topography (for example, the upper flanks of Mauna Kea are twice as steep as those of Mauna Loa; [figure 5]); and (3) different chemical compositions of the lava" (Clague and Dalrymple, 1987; USGS, 2002).

Gravity model. Investigations by Kauahikaua and others (2000) determined a three-dimensional gravity model for the Island of Hawai`i distinguished the five volcanic centers comprising the island: Kohala, Mauna Kea, Hualalai, Mauna Loa, and Kīlauea (figure 6). The base data for that map came from more than 3,300 gravity measurements made above sea level. Positive gravity anomalies define gravitationally dense zones caused by intrusions and cumulates beneath the summit and known rift zones of each of the five volcanoes composing the island. Figure 6 maps the 3-dimensional structure as modeled from the gravity data and expresses the gravity anomalies in terms of elevation from the overlying ground surface.

"Mauna Kea has an elliptical-shaped core, slightly elongated east-west, with a broad, linear feature trending southeast. This linear feature may be a buried rift zone of Mauna Kea, although no surface expressions of those rift zones have been mapped (Kauahikaua and others, 2000)."

The submarine feature known as the Hilo Ridge was also included in the density study with data contributed by GLORIA (a side-scan sonar) as well as satellites ERS-1, Geosat, and Seasat. Prior to this investigation, the Hilo Ridge had been attributed to Mauna Kea as its possible rift zone; however, the authors determined a stronger connection with Kohala due to multiple factors including the strongly NW-trending linear zone that extends ~80 km from the modelled core of Kohala.

Early European observations. An early survey of Hawai`i was conducted by Archibald Menzies, a botanist who accompanied Captain George Vancouver during the cruises of 1792-1794. Menzies successfully ascended Mauna Loa in February 1794 (a team from Captain Cook's crew had unsuccessfully attempted the summit in 1779; see figure 7). Menzies estimated the heights of Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea to within 31 m of the currently accepted value, "a remarkable surveying feat for that time" (Wright and others, 1992b).

The first petrologist to study Mauna Kea, R.A. Daly, determined not only that Mauna Kea's upper flanks were dominated by lava flows more rich in silica (he called them "andesite" although current classifications label them "hawaiite"), but also that the edifice had been modified by glaciers (Wolfe and others, 1997; Daly, 1911). Stearns and Macdonald (1946) and Washington (1923) expanded the knowledge base of Mauna Kea's geochemistry, and Gregory and Wentworth (1937) established that the glacial features from the most recent glacial episode (40,000 to 13,000 years ago) were interspersed with primary volcanic material. Wolfe and others (1997) determined that "eruptive activity of Mauna Kea was partly contemporaneous with that at Kohala, Hualalai, and Mauna Loa, and the volcano boundaries are undoubtedly complex."

HVO Volcano Watch article highlights a Mauna Kea forecast. The potential for a future eruption from Mauna Kea was addressed in a Volcano Watch article posted in June 2000 by then Scientist-in-Charge, Don Swanson, from the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) (Swanson, 2000ab). The article addresses not only eruption frequency but also trends in eruption style, the potential response of the telescope installation at Mauna Kea's summit, and a general forecast for a likely scenario in the future.

"The next eruption of Mauna Kea."

"Mauna Kea's peaceful appearance is misleading. The volcano is not dead. It erupted many times between 60,000 and 4,000 years ago, and some periods of quiet during that time apparently lasted longer than 4,000 years. Given that record, future eruptions seem almost certain.

"Before the next one, we should have ample warning provided by our current seismic and geodetic monitoring systems. A number of earthquakes occur beneath Mauna Kea each year, and you can bet that we pay close attention to them. However, they all appear to be associated with tectonic faulting rather than movement of magma.

"The telescopes on top of the volcano may be the first to indicate that something is amiss. The coordinates used for tracking their observations will begin to drift unexpectedly as the volcano is swelling. In a sense, the telescopes will serve as very expensive tiltmeters.

"We cannot now say when the next eruption will take place, except that it is unlikely to be in the next several months, given the current lack of any precursory signs. Whether the timing is years, centuries, or millennia is entirely unclear.

"But we can say something about the probable nature of the next eruption, because we know what the most recent ones were like, thanks to recently published research by Ed Wolfe [see Wolfe and others, 1997], former staff member of HVO, and colleagues.

"The next eruption could take place anywhere on the upper flanks of the volcano. As Mauna Kea evolved from its early shield stage (equivalent to Kīlauea and Mauna Loa today) to its present postshield stage, the volcano lost its rift zones. Consequently, the postshield eruptions are not concentrated along narrow zones but instead are scattered across the mountain. [See figure 6.]

"For example, the most recent eruptive period, 6,000-4,000 years ago, involved eight vents on the south flank of the volcano between Kala`i`eha cone (near Humu`ula) and Pu`ukole (east of Hale Pohaku). During this same period, eruptions took place on the northeast flank at Pu`u Lehu and Pu`u Kanakaleonui. Lava from Pu`u Kanakaleonui flowed more than 20 km (12 miles) northeastward, entering the sea to form Laupahoehoe Point.

"The next eruption will likely produce a lava flow, because each eruption in the past 60,000 years has done so. The longest flows will reach 15-25 km (9-15 miles) downslope. Most of each flow will be `a`a, but pahoehoe may form near vents.

"A prominent cinder cone will probably be constructed at each vent. The cinder cones responsible for the "bumpy" appearance of Mauna Kea's surface formed during the 60,000-4,000-year interval. The cones mentioned by name above, and several others, were built during the latest eruptive period 6,000-4,000 years ago. The next eruption will likely produce a similar cone.

"Cinder cones form at vents that are point sources, not elongate fissures. All activity is concentrated at one place, so that fountaining and spattering build a high cone rather than a long rampart. Past eruptions-and hence future ones--probably lasted months to several years, providing enough time to construct a substantial cone. Those eruptions spread voluminous ash deposits far beyond the cinder cones themselves, and the next eruption will probably do so, too.

"Possibly, however, there will not be enough spattering to build a lasting cone. Such an eruption happened about 1 km (0.6 miles) southeast of Hale Pohaku, when a vent put out a moderate volume of lava without building a spatter or cinder cone.

"The next eruption of Mauna Kea is unlikely to occur in our lifetimes, but it could. There is no reason to fear such an eruption. It would not threaten human life, provided due care were taken, though it could prove devastating to property and infrastructure, particularly if a lava flow traveled to the Hamakua coast or the Waimea area."

Mauna Kea's seismicity. HVO has monitored and maintained the record of seismicity for the entire region of Hawai`i. The seismicity detected beneath Mauna Kea has been characterized as "infrequent and sparse." Notable seismicity occurred in 1994, 2001, and 2011, when earthquakes were large enough to be felt by the general public. Island-wide instrumentation allowed excellent location data for the local seismicity (figure 8).

|

Figure 8. The seismic network that monitors Mauna Kea and the other volcanoes of Hawai`i spans six islands. This map appeared in the USGS Fact Sheet released in 2011. |

HVO reported that, several times each year, earthquakes from Mauna Kea cause shaking that is noted by local populations - especially the operators of the Mauna Kea astronomical observatory, who rely on stable instrumentation in order to make precise observations. Reports of felt earthquakes from Mauna Kea correlated with magnitude 2.1-4.9 earthquakes during 1973-2012.

Elevated seismicity during October-December 2011 resulted in 30 felt earthquakes. Approximately 570 people reported the M 4.5 earthquake that occurred on 20 October 2011 and also 10 of the aftershocks that followed (figure 9). HVO reported that, like many of Mauna Kea's earthquakes, these earthquakes were "most likely caused by structural adjustments within the Earth's crust due to the heavy load of Mauna Kea." With an estimated volume of >30,000 km3, Mauna Kea rises ~10,000 m above the seafloor, causing stress to accumulate from the mass of the volcano (Lockwood and Hazlett, 2010).

Earthquake swarms at Mauna Kea. HVO reported that earthquake swarms occasionally occur at Mauna Kea. On 23 February 2001, a swarm of ~15 events was detected within a 21-hour period. These earthquakes were mainly located ~15 km S of Pa`auilo (~3 km NW of Kuka`iau, figure 10), at a depth of 8-11 km.

Lake Waiau recedes. The cinder cone Pu`uwaiau, located within 2 km of the summit, has contained a freshwater lake that was considered permanent by Wolfe and others (1997) (figures 11 and 12). Lake Waiau has likely persisted due to the once-glassy cinders and bombs that have weathered to smectite with zeolites within the void spaces. These alteration products may serve as a weak cement between the pyroclasts and reduce the permeability of the cinder cone's base. Sporadic winter storms have provided most, if not all, of the water captured in this considerably arid region (Patrick and Delparte, 2014). Contributions from permafrost were also proposed by Woodcock (1980), but the presence of permafrost has not been confirmed near Lake Waiau.

Patrick and Delparte (2014) reported that the lake size before 2010 was 5,000-7,000 m2 with a depth of ~3 m, but recently, the size has been decreasing rapidly. In the recent past, the lake was known to overflow through the Pohakuloa Gulch when water levels exceeded the rim (as recently as February 2002) (Ehlmann and others, 2005).

Researchers have determined that Lake Waiau is sensitive to precipitation levels (Woodcock, 1980) and that ongoing drought conditions could be driving the lake's change (Patrick and Delparte, 2014). Based on the National Drought Mitigation Center's data, since 2008, and notably in March 2010, precipitation has been sparse at the summit of Mauna Kea.

In December 2013, scientists visited the lake and observed an unprecedented sight (figure 13). Lake Waiau measured a mere 115 m2 and was roughly 10-20 cm deep (Patrick and Delparte, 2014). While the lake size was known to fluctuate over time, this dramatic reduction has caused concern, given the possibility of losing a specialized ecosystem as well as a prominent feature of Hawaiian ethnogeography. Mauna Kea's summit is considered "one of the most sacred spots in the Hawaiian Islands. Archaeological sites near the summit attest to its prolonged spiritual importance...(Patrick and Delparte, 2014)."

USGS scientists at HVO as well as collaborators, including Idaho State University, continued to study the conditions at Lake Waiau after the significant survey was conducted in December 2013. As of May 2014, strong winter rains had partially restored the lake, providing stronger evidence that the multi-year shrinkage was due to the ongoing drought as opposed to changes in the volcanic system.

A note regarding the name Mauna Kea. The popular translation of the Hawaiian name Mauna Kea is frequently "White Mountain," however, significant discussions have focused on the source of the name. There has been growing consensus that Mauna Kea is a shortened form of Mauna a Wakea, which refers to the sky father Wakea.

According to testaments presented in the Final Environmental Impact Statement of the Federal Highway Administration Project No. A-AD-6(1) which included potential cultural impacts on the island by expanding State Routes 190 and 200, "The mountain is the sacred child of Wakea, and it is the source for the land. The mountains and land were genealogically connected to native Hawaiians through the original ancestor, Wakea [sky father] and Papa [earth mother]."

Ethnographic research conducted prior to 1999 and released in the impact statement concluded that the summit area of Mauna Kea was eligible for the National Register of Historic Places due to traditional cultural property.

A note regarding Hawaiian names and nomenclature. As previously noted in other Bulletin reports, according to Runyon (2006), "The U.S. Board on Geographic Names (BGN) is responsible for establishing and maintaining uniform geographical name usage throughout all departments and agencies of the United States government. As such, the Board collects and promulgates every name that is considered official for Federal use. The official vehicle for promulgating these names and their locative attributes is the Geographic Names Information System (GNIS).

"Until the 1990's, it was also Federal policy to omit most diacritics and writing marks from placenames on Federal maps and documents. The few exceptions included the Spanish tilde and the French accent marks, but otherwise the special characters found in indigenous names were always dropped. In more recent years, however, the BGN has amended its policy to permit the inclusion of such marks, thus more accurately reflecting the true representation of the native language. An example of this has been the addition of the glottal stop (okina) and macron (kahako) to placenames of Hawaiian origin, which prior to 1995 had always been omitted. The BGN staff, under the direction and guidance of the Hawaii State Geographic Names Authority, has been restoring systemically these marks to each Hawaiian name listed in GNIS."

GVP will strive to conform to GNIS nomenclature. It remains a technological challenge, but a goal.

References: Clague, D.A., and Dalrymple, G.B., 1987, The Hawaiian-Emperor volcanic chain. Part I. Geologic evolution, chap. 1 of Decker, R.W, Wright, T.L., and Stauffer, PH., eds., Volcanism in Hawaii: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1350, v. 1, p. 5-54.

Daly, R.A., 1911, Magmatic differentiation in Hawaii: Journal of Geology, v. 19, no. 4, p. 289-316.

Federal Highway Administration, 1999, Final Environmental Impact Statement Part 1: Hawaii State Route 200, Mamalahoa Highway (SR 190) to Milepost 6 Saddle Road, County of Hawai`i, State of Hawai`i, FHWA Project No. A-AD-6(1).

Ehlmann, B.L., Arvidson, R.E., Jolliff, B.L., Johnson, S.S., Ebel, B., Lovenduski, N., Morris, J.D., Beyers, J.A., Snider, N.O., and Criss, R.E., 2005. Hydrologic and isotopic modeling of Alpine Lake Waiau, Mauna Kea, Hawai`i. University of Hawaii Press, p. 1-15.

Fitzpatrick, G.L, 1986. The early mapping of Hawaii. Honolulu: Editions Limited, vol. 1, 160 pp.

Geohazards Consultants International, Inc., Mauna Kea Science Reserve Master Plan, Volcano, HI, March 2000, 22 p.

Gregory, H.E., and Wentworth, C.K., 1937, General features and glacial geology of Mauna Kea, Hawaii: Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 48, no. 12, p. 1719-1742.

Holt, Rinehart, and Winston (2006), Hawaii. Retrieved from http://go.hrw.com/atlas/norm_htm/hawaii.htm.

Hoover, S.R. and Fodor, R.V., 1997, Magma-reservoir crystallization processes: small-scale dikes in cumulate gabbros, Mauna Kea Volcano, Hawaii, Bulletin of Volcanology, 59, p. 186-197.

Kauahikaua, J., Hildenbrand, T., & Webring, M., 2000. Deep magmatic structures of Hawaiian volcanoes, imaged by three-dimensional gravity models. Geology, 28, 10, p. 883.

Lockwood, J.P., and Hazlett, R.W., 2010. Volcanoes: Global Perspectives, Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, NJ, ix, 539 p.

Okubo, P.G. and Nakata, J.S., 2011, Earthquakes in Hawai`i-An Underappreciated but Serious Hazard, Fact Sheet 2011-3013, USGS Fact Sheet, September 2011. (http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2011/3013/)

Patrick, M. R. and Delparte, D., 2014, Tracking Dramatic Changes at Hawaii's Only Alpine Lake: EOS (Transactions, American Geophysical Union), Vol. 95, No. 14, p. 117-118.

Porter, S.C., 1971, Holocene Eruptions of Mauna Kea Volcano, Hawaii, Science, Vol. 172 no. 3981 p. 375-377.

Stearns, H.T., and Macdonald, G.A., 1946, Geology and ground-water resources of the Island of Hawaii: Hawaii Division of Hydrography Bulletin 9, 363 p.

Swanson, D.A., (June 2000a). The next eruption of Mauna Kea. Volcano Watch. Retrieved from http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanowatch/archive/2000/00_06_01.html.

Swanson, D.A., 2000b, Don't be fooled by seemingly peaceful Mauna Kea Volcano--it could erupt again: Hawaii Tribune-Herald, June 4, p. 2.

USGS-HVO (May 2002). Mauna Kea Hawai`i's Tallest Volcano. Other Volcanoes. Retrieved from http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanoes/maunakea/.

Washington, H.S., 1923, Petrology of the Hawaiian Islands; I, Kohala and Mauna Kea, Hawaii: American Journal of Science, ser. 5, v. 5, no. 30, p. 465-502.

Wolfe, E.W., Wise, W.S., and Dalrymple, G.B., 1997, The geology and petrology of Mauna Kea volcano, Hawaii: a study of postshield volcanism. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1557, Washington, D.C.: U.S. G.P.O.

Woodcock, A., 1980. Hawaiian alpine lake level, rainfall trends, and spring flow, Pacific Science, 34, p. 195–209.

Wright, T.L., Chu, J.Y., Esposo, J., Heliker, C., Hodge, J., Lockwood, J.P., and Vogt, S.M., 1992a, Map showing lava-flow hazard zones, island of Hawaii: U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Field Studies Map MF-2193, scale 1:250,000.

Wright, T.L., Takahashi, T.J., and Griggs, J.D., 1992b, Hawai`i Volcano Watch: A Pictorial History, 1779-1991, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 162 p.

Information Contacts: Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO), U.S. Geological Survey, PO Box 51, Hawai`i National Park, HI 96718, USA (URL: https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/observatories/hvo/); Richard Wainscoat, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Institute for Astronomy (URL: http://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/, http://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/images/aerial-tour-95/); Scott Rowland, University of Hawaii at Manoa, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (URL: http://www.soest.hawaii.edu/); and Hawaii News Now (URL: http://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/).

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There is data available for 6 confirmed eruptive periods.

2460 BCE ± 100 years Confirmed Eruption (Explosive / Effusive)

| Episode 1 | Eruption (Explosive / Effusive) | NE flank (Puu Lehu, 3130 m) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2460 BCE ± 100 years - Unknown | Evidence from Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

List of 3 Events for Episode 1 at NE flank (Puu Lehu, 3130 m)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

2540 BCE ± 200 years Confirmed Eruption (Explosive / Effusive)

| Episode 1 | Eruption (Explosive / Effusive) | South rift zone (Puu Kole) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2540 BCE ± 200 years - Unknown | Evidence from Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

List of 2 Events for Episode 1 at South rift zone (Puu Kole)

|

|||||||||||||||||||

2750 BCE ± 200 years Confirmed Eruption (Explosive / Effusive)

| Episode 1 | Eruption (Explosive / Effusive) | NE flank (Puu Kanakaleonui, 2930 m) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2750 BCE ± 200 years - Unknown | Evidence from Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

List of 3 Events for Episode 1 at NE flank (Puu Kanakaleonui, 2930 m)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

3370 BCE ± 150 years Confirmed Eruption (Explosive / Effusive)

| Episode 1 | Eruption (Explosive / Effusive) | SE flank (near Hale Pohaku, 2740 m) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3370 BCE ± 150 years - Unknown | Evidence from Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

List of 4 Events for Episode 1 at SE flank (near Hale Pohaku, 2740 m)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

3680 BCE ± 200 years Confirmed Eruption (Explosive / Effusive)

| Episode 1 | Eruption (Explosive / Effusive) | South rift zone (Puu Kalaieha) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3680 BCE ± 200 years - Unknown | Evidence from Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

List of 4 Events for Episode 1 at South rift zone (Puu Kalaieha)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

5150 BCE ± 150 years Confirmed Eruption (Explosive / Effusive)

| Episode 1 | Eruption (Explosive / Effusive) | North flank (Puu Kole) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5150 BCE ± 150 years - Unknown | Evidence from Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

List of 4 Events for Episode 1 at North flank (Puu Kole)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This compilation of synonyms and subsidiary features may not be comprehensive. Features are organized into four major categories: Cones, Craters, Domes, and Thermal Features. Synonyms of features appear indented below the primary name. In some cases additional feature type, elevation, or location details are provided.

Cones |

||||

| Feature Name | Feature Type | Elevation | Latitude | Longitude |

| Ahumoa | Cone | 2207 m | 19° 49' 0.00" N | 155° 37' 0.00" W |

| Haiwahine, Puʻu | Cone | 2865 m | 19° 46' 0.00" N | 155° 28' 0.00" W |

| Hiukau, Puʻu | Cone | 2234 m | 19° 43' 0.00" N | 155° 26' 0.00" W |

| Hookomo, Puʻu | Cone | 2403 m | 19° 44' 0.00" N | 155° 27' 0.00" W |

| Kalaieha, Puʻu | Cone | 2141 m | 19° 42' 0.00" N | 155° 26' 0.00" W |

| Kalepeamoa, Puʻu | Cone | 2863 m | 19° 45' 0.00" N | 155° 28' 0.00" W |

| Kanakaleonui, Puʻu | Cone | 2947 m | 19° 52' 0.00" N | 155° 23' 0.00" W |

| Kole, Puʻu | Cone | 2993 m | 19° 45' 0.00" N | 155° 25' 0.00" W |

| Lehu, Puʻu | Cone | 3130 m | 19° 52' 30.00" N | 155° 26' 0.00" W |

| Loa, Puʻu | Cone | 2384 m | 19° 46' 0.00" N | 155° 23' 0.00" W |

| Loaloa, Puʻu | Cone | 2334 m | 19° 44' 0.00" N | 155° 26' 0.00" W |

| Makanaka, Puʻu | Cone | 3784 m | 19° 50' 30.00" N | 155° 26' 0.00" W |

| Omaokoili | Cone | 2161 m | 19° 43' 0.00" N | 155° 30' 0.00" W |

| Poliahu, Puʻu | Cone | 4155 m | 19° 49' 0.00" N | 155° 29' 0.00" W |

| Wekui, Puʻu | Cone | 4205 m | 19° 49' 0.00" N | 155° 28' 0.00" W |

Craters |

||||

| Feature Name | Feature Type | Elevation | Latitude | Longitude |

| South Rift Zone | Fissure vent | 19° 45' 0.00" N | 155° 27' 0.00" W | |

This 1975 photo of the snow-covered summit of Mauna Loa from the SW shows the 2.4 x 4.8 km wide Moku‘āweoweo caldera in the center, with three circular craters in the foreground. South Pit (merging with the SW caldera rim), Lua Hohonu, and Hua Hou (foreground), formed through collapse along the upper SW rift zone. Mauna Kea is in the distance.

This 1975 photo of the snow-covered summit of Mauna Loa from the SW shows the 2.4 x 4.8 km wide Moku‘āweoweo caldera in the center, with three circular craters in the foreground. South Pit (merging with the SW caldera rim), Lua Hohonu, and Hua Hou (foreground), formed through collapse along the upper SW rift zone. Mauna Kea is in the distance. Calderas at the summits of basaltic shield volcanoes, such as this one at Hawaii's Mauna Loa volcano differ from those formed at more silicic stratovolcanoes. The 2.4 x 4.8 km wide Mokuaweoweo caldera, seen here from the south with Mauna Kea volcano in the background, formed when the summit collapsed after large amounts of magma were siphoned away from the summit region by flank eruptions or lava intrusions. The elongate, scalloped form of the caldera reflects both the influence of rift systems and the incremental growth of the caldera.

Calderas at the summits of basaltic shield volcanoes, such as this one at Hawaii's Mauna Loa volcano differ from those formed at more silicic stratovolcanoes. The 2.4 x 4.8 km wide Mokuaweoweo caldera, seen here from the south with Mauna Kea volcano in the background, formed when the summit collapsed after large amounts of magma were siphoned away from the summit region by flank eruptions or lava intrusions. The elongate, scalloped form of the caldera reflects both the influence of rift systems and the incremental growth of the caldera. Broad streams of incandescent lava travel down the NE rift zone of Mauna Loa volcano early in the morning of March 25, 1984, with Mauna Kea volcano in the background to the north. The eruptive fissure initially opened in the summit caldera and SW rift zone, but soon migrated down the NE rift zone, where activity continued until the eruption ended on April 15. Lava flows from the NE rift zone traveled down the NE and SE flanks, reaching to within about 5 km of the city limits of Hilo.

Broad streams of incandescent lava travel down the NE rift zone of Mauna Loa volcano early in the morning of March 25, 1984, with Mauna Kea volcano in the background to the north. The eruptive fissure initially opened in the summit caldera and SW rift zone, but soon migrated down the NE rift zone, where activity continued until the eruption ended on April 15. Lava flows from the NE rift zone traveled down the NE and SE flanks, reaching to within about 5 km of the city limits of Hilo. Hawaii's two largest shield volcanoes are Mauna Loa (in the background to the S) and Mauna Kea. Mauna Loa has the classic low-angle profile of a shield volcano constructed by repetitive eruptions of thin, overlapping lava flows. Mauna Kea’s profile has been modified by late-stage explosive eruptions that constructed a series of cones at the summit.

Hawaii's two largest shield volcanoes are Mauna Loa (in the background to the S) and Mauna Kea. Mauna Loa has the classic low-angle profile of a shield volcano constructed by repetitive eruptions of thin, overlapping lava flows. Mauna Kea’s profile has been modified by late-stage explosive eruptions that constructed a series of cones at the summit. Scoria cones across the snow-covered Mauna Kea summit are some of the most recent features of this volcano, seen here from the SW. The high altitude makes it the only Hawaiian volcano that is known to have had glaciers.

Scoria cones across the snow-covered Mauna Kea summit are some of the most recent features of this volcano, seen here from the SW. The high altitude makes it the only Hawaiian volcano that is known to have had glaciers. This view of Mauna Kea from the north shows the irregular profile of the summit. The scoria cones in the center of this photo were constructed during eruptions about 4,500 years ago.

This view of Mauna Kea from the north shows the irregular profile of the summit. The scoria cones in the center of this photo were constructed during eruptions about 4,500 years ago. The Pu‘u Haukea scoria cone is one of many recent cones that have formed near the Mauna Kea summit. Mauna Loa is in the background with unvegetated lava flows visible down its flanks. Nearly the entire Mauna Loa surface seen here consists of lava flows erupted during the past 4,000 years.

The Pu‘u Haukea scoria cone is one of many recent cones that have formed near the Mauna Kea summit. Mauna Loa is in the background with unvegetated lava flows visible down its flanks. Nearly the entire Mauna Loa surface seen here consists of lava flows erupted during the past 4,000 years. Mauna Kea is seen here from the north along the broad Mauna Loa NE rift zone. The scoria cones that formed during recent eruptions give the volcano an irregular profile.

Mauna Kea is seen here from the north along the broad Mauna Loa NE rift zone. The scoria cones that formed during recent eruptions give the volcano an irregular profile. Mauna Kea (left) and Mauna Loa (right), both over 4,000 m above sea level, are also the world's largest active volcanoes, rising nearly 9 km above the sea floor around the island of Hawai’i. This aerial view from the NW shows the contrasting morphologies with the smooth profile of Mauna Loa, and Mauna Kea that was modified by the late-stage products of explosive eruptions.

Mauna Kea (left) and Mauna Loa (right), both over 4,000 m above sea level, are also the world's largest active volcanoes, rising nearly 9 km above the sea floor around the island of Hawai’i. This aerial view from the NW shows the contrasting morphologies with the smooth profile of Mauna Loa, and Mauna Kea that was modified by the late-stage products of explosive eruptions. Mauna Kea is seen here from the S at the broad Humu'ulu Saddle between Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa. The lava flow in the foreground was emplaced during an 1843 eruption that originated on the NE rift zone of Mauna Loa. The flow traveled directly N to the Mauna Kea saddle, where it was deflected to the W. The irregular profile of the summit region of Mauna Kea is due to scoria cones and pyroclastic ejecta that are not present at Mauna Loa.

Mauna Kea is seen here from the S at the broad Humu'ulu Saddle between Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa. The lava flow in the foreground was emplaced during an 1843 eruption that originated on the NE rift zone of Mauna Loa. The flow traveled directly N to the Mauna Kea saddle, where it was deflected to the W. The irregular profile of the summit region of Mauna Kea is due to scoria cones and pyroclastic ejecta that are not present at Mauna Loa.The following 474 samples associated with this volcano can be found in the Smithsonian's NMNH Department of Mineral Sciences collections, and may be availble for research (contact the Rock and Ore Collections Manager). Catalog number links will open a window with more information.

| Catalog Number | Sample Description | Lava Source | Collection Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| NMNH 102377-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 102377-2 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 102377-3 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 102377-4 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 110780 | Ankaramite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 111122-1 | Ultrabasic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 111122-1 | Ultrabasic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 111123-1849 | Trachydolerite | POLIAHU CONE | -- |

| NMNH 111123-1850 | Andesitic Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 111774 | Hawaiite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 111775 | Hawaiite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 111783 | Hawaiite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 111784 | Hawaiite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 111785 | Hawaiite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 111786 | Ankaramite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 111787 | Ankaramite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 111788 | Ankaramite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 111789 | Ankaramite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 111790 | Ankaramite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 112521-42 | Ankaramite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 112521-44 | Hawaiite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 112521-45 | Hawaiite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 112521-46 | Tholeiite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 112521-47 | Hawaiite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 112521-48 | Tholeiite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 112521-49 | Hawaiite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 112521-50 | Hawaiite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 112521-51 | Mugearite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 113095-1 | Picrite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 113095-1 | Picrite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 113095-14 | Hawaiite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 113095-16 | Ankaramite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-1 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-11 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-12 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-13 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-14 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-15 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-16 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-17 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-18 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-19 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-2 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-20 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-21 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-22 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-3 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-4 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-5 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-6 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-7 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-8 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114356-9 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114741-1 | Unidentified | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114741-10 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114741-11 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114741-2 | Unidentified | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114741-3 | Unidentified | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114741-4 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114741-5 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114741-6 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114741-7 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114741-8 | Diorite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114741-9 | Diorite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114747-1 | Olivine Dunite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114747-2 | Olivine Gabbro | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114747-3 | Olivine Dunite | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114779-1 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-10 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-11 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-12 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-13 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-14 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-15 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-16 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-17 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-18 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-19 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-2 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-20 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-21 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-22 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-23 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-24 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-25 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-26 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-27 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-28 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-29 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-3 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-30 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-31 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-32 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-33 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-34 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-35 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-36 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-37 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-38 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-39 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-4 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-40 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-41 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-42 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-43 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-44 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-45 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-46 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-47 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-48 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-49 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-5 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-50 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-51 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-52 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-53 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-54 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-55 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-56 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-57 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-6 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-7 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-8 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114779-9 | Ultramafic Nodule | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114780-1 | Andesite | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114780-2 | Andesite | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114780-3 | Andesite | HALE POHAKU | -- |

| NMNH 114781-1 | Basalt | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-1 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-10 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-11 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-12 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-13 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-14 | Olivine Gabbro | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-15 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114782-16 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-17 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-18 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-19 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-2 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-20 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-21 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-22 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-23 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-24 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-25 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-26 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-27 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-28 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-3 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-4 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-5 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-6 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-7 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-8 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114782-9 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KOOHI | -- |

| NMNH 114783-1 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-10 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-11 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-12 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-13 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-14 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-15 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-16 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-17 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-18 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-19 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-2 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-20 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-21 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-22 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-23 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-24 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-25 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-26 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-27 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-28 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-29 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU POLIAHU | -- |

| NMNH 114783-3 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-30 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU POLIAHU | -- |

| NMNH 114783-31 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU POLIAHU | -- |

| NMNH 114783-32 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU POLIAHU | -- |

| NMNH 114783-33 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU POLIAHU | -- |

| NMNH 114783-34 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU POLIAHU | -- |

| NMNH 114783-35 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU POLIAHU | -- |

| NMNH 114783-36 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU POLIAHU | -- |

| NMNH 114783-37 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU POLIAHU | -- |

| NMNH 114783-38 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU POLIAHU | -- |

| NMNH 114783-4 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-5 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-6 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-7 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-8 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114783-9 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114784-1 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114785-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114786-1 | Basalt | PUU HOLEI | -- |

| NMNH 114787-1 | Volcanic Rock | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114787-2 | Volcanic Rock | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114787-3 | Volcanic Rock | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114787-4 | Volcanic Rock | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114787-5 | Volcanic Rock | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-1 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-10 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-11 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-12 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-13 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-14 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-15 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-16 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-17 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-18 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-19 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-2 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-20 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-21 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-22 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-23 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-24 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-25 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-26 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-27 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-28 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-29 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-3 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-30 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-31 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-32 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-4 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-5 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-6 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-7 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-8 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114798-9 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU KANAKALEONUI | -- |

| NMNH 114799-1 | Volcanic Rock | PUU KEA | -- |

| NMNH 114800-1 | Volcanic Rock | PUU KALUAMAKANI | -- |

| NMNH 114800-2 | Volcanic Rock | PUU KALUAMAKANI | -- |

| NMNH 114800-3 | Volcanic Rock | PUU KALUAMAKANI | -- |

| NMNH 114800-4 | Volcanic Rock | PUU KALUAMAKANI | -- |

| NMNH 114802-1 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-10 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-11 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-12 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-13 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-14 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-15 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-16 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-17 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-18 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-19 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-2 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-20 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-21 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-22 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-23 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-24 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-25 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-26 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-28 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-29 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-3 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-30 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-4 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-5 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-6 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-7 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-8 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114802-9 | Ultramafic Nodule | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114803-1 | Basalt | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114803-2 | Basalt | KEMOLE | -- |

| NMNH 114804-1 | Basalt | PUU NANAHA | -- |

| NMNH 114805-1 | Ultramafic Nodule | PUU NANAHA | -- |

| NMNH 114805-2 | Basalt | PUU NANAHA | -- |

| NMNH 114806-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114807-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114807-2 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114807-3 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114807-4 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114808-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114808-2 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114808-3 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114808-4 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114808-5 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114808-6 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-1 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-10 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-11 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-12 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-13 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-14 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-15 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-16 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-17 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-18 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-19 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-2 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-20 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-21 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-22 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-23 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-3 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-4 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-5 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-6 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-7 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-8 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114809-9 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114810-1 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114811-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-1 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-10 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-11 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-12 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-13 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-14 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-15 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-16 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-17 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-18 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-19 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-2 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-20 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-3 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-4 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-5 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-6 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-7 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-8 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114812-9 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114813-1 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114813-2 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-1 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-10 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-11 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-12 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-13 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-14 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-15 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-16 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-17 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-18 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-19 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-2 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-20 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-21 | Gabbro | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-22 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-23 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-24 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-25 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-26 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-27 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-28 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-29 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-3 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-4 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-5 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-6 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-7 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-8 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114814-9 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114815-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114816-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114816-2 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114817-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114817-10 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114817-11 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114817-12 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114817-13 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114817-14 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114817-15 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114817-16 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114817-2 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114817-3 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114817-4 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114817-5 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114817-6 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114817-7 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114817-8 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114817-9 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114818-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114818-2 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114822-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114964-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114964-2 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114964-3 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114977-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114978-1 | Basalt | PUU KEONEHEHEE | -- |

| NMNH 114978-10 | Basalt | PUU KEONEHEHEE | -- |

| NMNH 114978-2 | Basalt | PUU KEONEHEHEE | -- |

| NMNH 114978-3 | Basalt | PUU KEONEHEHEE | -- |

| NMNH 114978-4 | Basalt | PUU KEONEHEHEE | -- |

| NMNH 114978-5 | Basalt | PUU KEONEHEHEE | -- |

| NMNH 114978-6 | Basalt | PUU KEONEHEHEE | -- |

| NMNH 114978-7 | Basalt | PUU KEONEHEHEE | -- |

| NMNH 114978-8 | Basalt | PUU KEONEHEHEE | -- |

| NMNH 114978-9 | Basalt | PUU KEONEHEHEE | -- |

| NMNH 114979-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114980-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114980-10 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114980-11 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114980-12 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114980-13 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114980-14 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114980-15 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114980-16 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114980-2 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114980-3 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114980-4 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114980-5 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114980-6 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114980-7 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114980-8 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114980-9 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114981-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114982-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114983-1 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114984-1 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114985-1 | Basalt | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114986-1 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114986-10 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114986-11 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114986-12 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114986-13 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114986-14 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114986-15 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114986-16 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114986-2 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114986-3 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114986-4 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114986-5 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |

| NMNH 114986-6 | Ultramafic Nodule | -- | -- |