Report on Long Valley (United States) — March 2012

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 37, no. 3 (March 2012)

Managing Editor: Richard Wunderman.

Edited by Robert Dennen.

Long Valley (United States) 2009 summary, deep seismic swarm at Mammoth Mountain

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 2012. Report on Long Valley (United States) (Dennen, R., and Wunderman, R., eds.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 37:3. Smithsonian Institution. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.BGVN201203-323822

Long Valley

United States

37.7°N, 118.87°W; summit elev. 3390 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

This report on Long Valley caldera, California, summarizes USGS reports for 2009. The volcano remained non-eruptive. Long Valley Observatory (LVO) is now part of the California Volcano Observatory (CalVO). A tectonic earthquake sequence during 2011 in nearby Hawthorne, Nevada, is also discussed.

Long Valley caldera entered relative quiescence in the spring of 1999 (BGVN 26:07) following unrest that began in 1980 (SEAN 07:05); this relative quiescence continued through 2009.

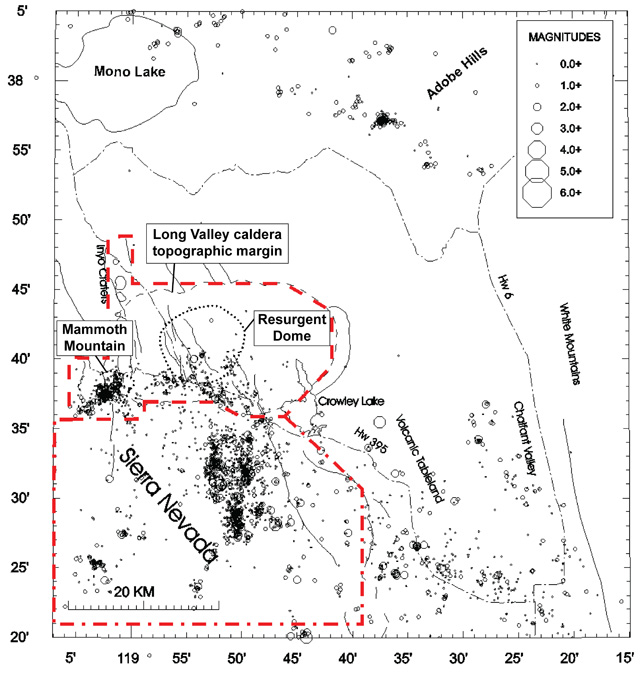

Seismicity during 2009 was characterized by a low level of seismicity within the caldera, and a typical higher level of seismicity in the surrounding Sierra Nevada range (figure 41). Three recorded earthquakes were larger than M 3.0, yet none of them occurred within the region of Long Valley caldera as delimited by LVO. The largest earthquakes within Long Valley caldera were an M 2.7 on 9 January in the S moat, and a pair of M 2.3 earthquakes on 10 December that were located beneath the resurgent dome.

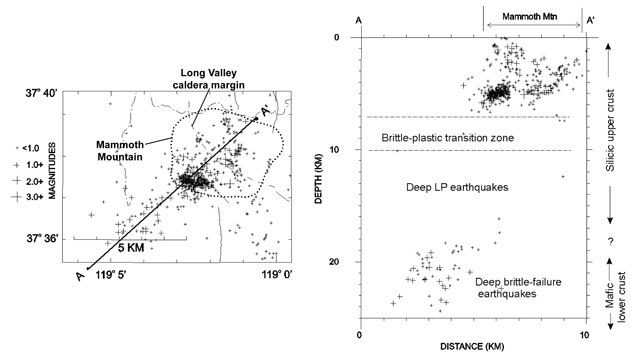

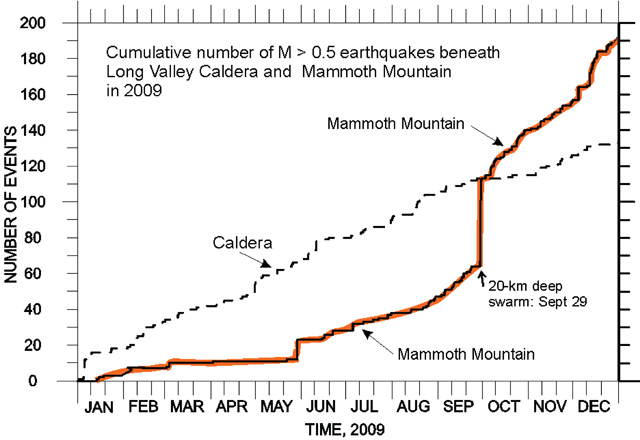

Deep seismic swarm at Mammoth Mountain.At Mammoth Mountain, increased seismicity began in late May, and a deep seismic swarm occurred on 29 September. The 29 September seismic swarm included over 50 M ≥0.5 high-frequency earthquakes that occurred at depths of 20-25 km, depths inferred to be in the mafic lower crust (figure 42). The high frequencies of these earthquakes indicated brittle-rock failure similar to shallow earthquakes that typically occur at <10 km depth, and were distinctly different than the long-period earthquakes that occur within the silicic upper crust, at depths of 10-25 km. The increased seismicity at Mammoth Mountain during 2009 produced more earthquakes there than occurred within Long Valley caldera (figures 41, 42, and 43).

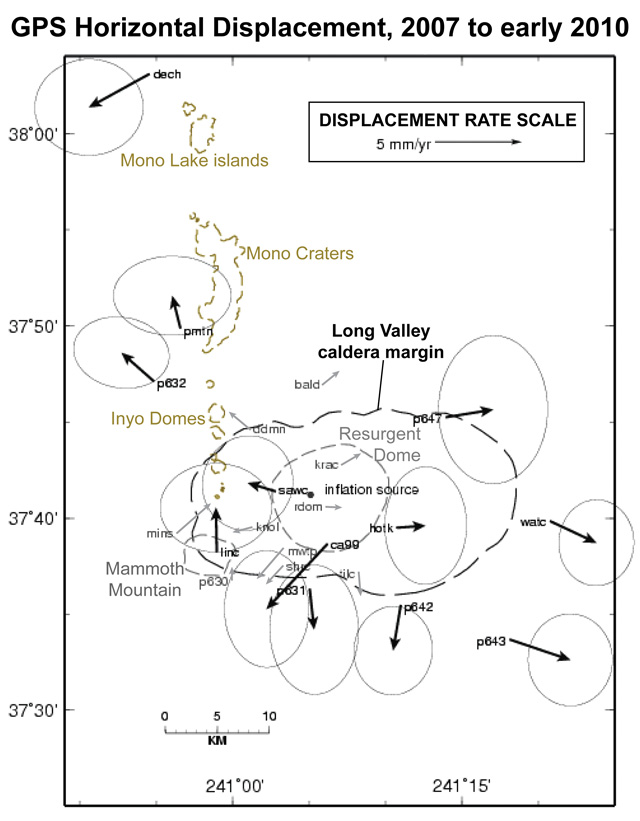

Slow inflation of the caldera's resurgent dome. Deformation trends during 2007-2009 highlighted slow inflation of the resurgent dome. At the end of 2009, the height of the resurgent dome remained ~75 cm higher than prior to the onset of unrest in 1980. Measurements since 2007 indicated horizontal displacement rates of ~5 mm/year, mostly in a pattern radiating away from the resurgent dome (figure 44).

During 2009, soil CO2 emission measurements revealed variations typical of most previous years. The increase in seismicity at Mammoth Mountain on 29 September did not produce a corresponding increase in CO2 emissions.

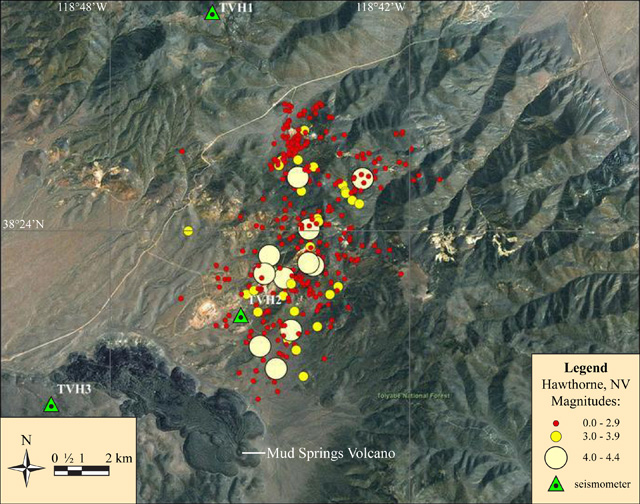

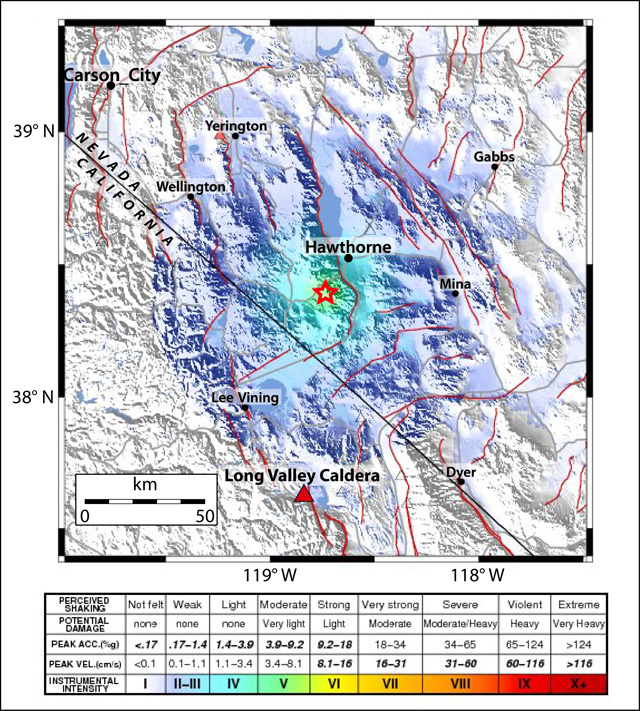

2011 Hawthorne, Nevada, earthquake sequence. In March 2011, an earthquake sequence (mentioned in LVO weekly activity updates) began in Hawthorne, Nevada (~100 km NNE of the center of Long Valley caldera) that, according to Smith and others (2011), initially sparked brief concerns of unrest at Mud Springs volcano (figure 45). Mud Springs volcano is a probable Pleistocene volcano of the Aurora-Bodie volcanic field, Nevada (Wood and Kienle, 1992). The Hawthorne earthquakes did not show volcanic signatures in near-source seismograms (Smith and others, 2011), and the sequence was quickly identified as tectonic in origin.

According to Smith and others (2011), "An additional concern, as the sequence . . . proceeded, was a clear progression eastward toward the Wassuk Range front fault. The east dipping range bounding fault is capable of M 7+ events, and poses a significant hazard to the community of Hawthorne and local military facilities. The Hawthorne Army Depot is an ordinance storage facility and the nation's storage site for surplus mercury."

Earthquakes of the March 2011 sequence were as strong as M 4.6 (figure 46); the largest earthquakes may have been felt in Bridgeport, CA (~60 km SW of Hawthorne, and ~70 km NNW from the center of Long Valley caldera), according to LVO. The earthquakes occurred along at least two shallow faults, originating at 2-6 km depth (Smith and others, 2011). The earthquake sequence "slowly decreased in intensity through mid-2011" (Smith and others, 2011).

References. Smith, K.D., Johnson, C., Davies, J.A., Agbaje, T., Antonijevic, S.K., and Kent, G., 2011. The 2011 Hawthorne, Nevada, Earthquake Sequence; Shallow Normal Faulting. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2011, Abstract ##S53B-2284.

Wood, C.A. and Kienle, J., 1992. Volcanoes of North America: United States and Canada, Cambridge University Press, 354 p., pgs. 256-262.

Geological Summary. The large 17 x 32 km Long Valley caldera east of the central Sierra Nevada Range formed as a result of the voluminous Bishop Tuff eruption about 760,000 years ago. Resurgent doming in the central part of the caldera occurred shortly afterwards, followed by rhyolitic eruptions from the caldera moat and the eruption of rhyodacite from outer ring fracture vents, ending about 50,000 years ago. During early resurgent doming the caldera was filled with a large lake that left strandlines on the caldera walls and the resurgent dome island; the lake eventually drained through the Owens River Gorge. The caldera remains thermally active, with many hot springs and fumaroles, and has had significant deformation, seismicity, and other unrest in recent years. The late-Pleistocene to Holocene Inyo Craters cut the NW topographic rim of the caldera, and along with Mammoth Mountain on the SW topographic rim, are west of the structural caldera and are chemically and tectonically distinct from the Long Valley magmatic system.

Information Contacts: Dave Hill, California Volcano Observatory (CalVO), formerly theLong Valley Observatory (LVO), U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA (URL: http://volcanoes.usgs.gov/observatories/calvo/); Nevada Seismological Laboratory, Laxalt Mineral Engineering Building, Room 322, University of Nevada-Reno, Reno, NV 89557 (URL: http://www.seismo.unr.edu/).