Report on Pacaya (Guatemala) — February 2020

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 45, no. 2 (February 2020)

Managing Editor: Edward Venzke.

Edited by Kadie L. Bennis.

Pacaya (Guatemala) Continuous explosions, small cone, and lava flows during August 2019-January 2020

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 2020. Report on Pacaya (Guatemala) (Bennis, K.L., and Venzke, E., eds.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 45:2. Smithsonian Institution. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.BGVN202002-342110

Pacaya

Guatemala

14.382°N, 90.601°W; summit elev. 2569 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Pacaya is a highly active basaltic volcano located in Guatemala with volcanism consisting of frequent lava flows and Strombolian explosions originating in the Mackenney crater. The previous report summarizes volcanism that included multiple lava flows, Strombolian activity, avalanches, and gas-and-steam emissions (BGVN 44:08), all of which continue through this reporting period of August 2019 to January 2020. The primary source of information comes from reports by the Instituto Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanologia, Meteorologia e Hydrologia (INSIVUMEH) in Guatemala and various satellite data.

Strombolian explosions occurred consistently throughout this reporting period. During the month of August 2019, explosions ejected material up to 30 m above the Mackenney crater. These explosions deposited material that contributed to the formation of a small cone on the NW flank of the Mackenney crater. White and occasionally blue gas-and-steam plumes rose up to 600 m above the crater drifting S and W. Multiple incandescent lava flows were observed traveling down the N and NW flanks, measuring up to 400 m long. Small to moderate avalanches were generated at the front of the lava flows, including incandescent blocks that measured up to 1 m in diameter. Occasionally incandescence was observed at night from the Mackenney crater.

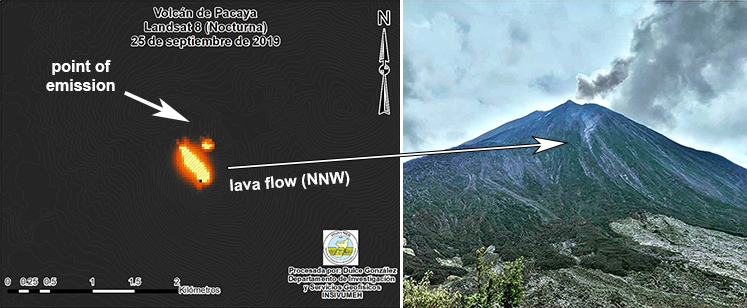

In September 2019 seismicity was elevated compared to the previous month, registering a maximum of 8,000 RSAM (Realtime Seismic Amplitude Measurement) units. White and occasionally blue gas-and-steam plumes that rose up to 1 km above the crater drifted generally S as far as 3 km from the crater. Strombolian explosions continued, ejecting material up to 100 m above the crater rim. At night and during the early morning, crater incandescence was observed. Incandescent lava flows traveled as much as 600 m down the N and NW flanks toward the Cerro Chino crater (figure 116). On 21 September two lava flows descended the SW flank. Constant avalanches with incandescent blocks measuring 1 m in diameter occurred from the front of many of these lava flows.

Weak explosions continued through October 2019, ejecting material up to 75 m above the crater and building a small cone within the crater. White and occasionally blue gas-and-steam plumes rose 400-800 m above the crater, drifting W and NW and extending up to 4 km from the crater during the week of 26 October-1 November. Lava flows measuring up to 250 m long, originating from the Mackenney crater were descending the N and NW flanks (figure 117). Avalanches carrying large blocks 1 m in diameter commonly occurred at the front of these lava flows.

|

Figure 117. Photo of lava flows traveling down the flanks of Pacaya taken between 28 September 2019 and 4 October. Courtesy of INSIVUMEH (28 September 2019 to 4 October Weekly Report). |

Continuing Strombolian explosions in November 2019 ejected material 15-75 m above the crater, which then contributed to the formation of the new cone. White and occasionally blue gas-and-steam plumes rose 100-600 m above the crater drifting in different directions and extending up to 2 km. Multiple lava flows from the Mackenney crater moving down all sides of the volcano continued, measuring 50-700 m long. Avalanches were generated at the front of the lava flows, often moving blocks as large as 1 m in diameter. The number of lava flows decreased during 2-8 November and the following week of 9-15 November no lava flows were observed, according to INSIVUMEH. During the week of 16-22 November, a small collapse occurred in the Mackenney crater and explosive activity increased during 16, 18, and 20 November, reaching RSAM units of 4,500. At night and early morning in late November crater incandescence was visible. On 24 November two lava flows descended the NW flank toward the Cerro Chino crater, measuring 100 m long.

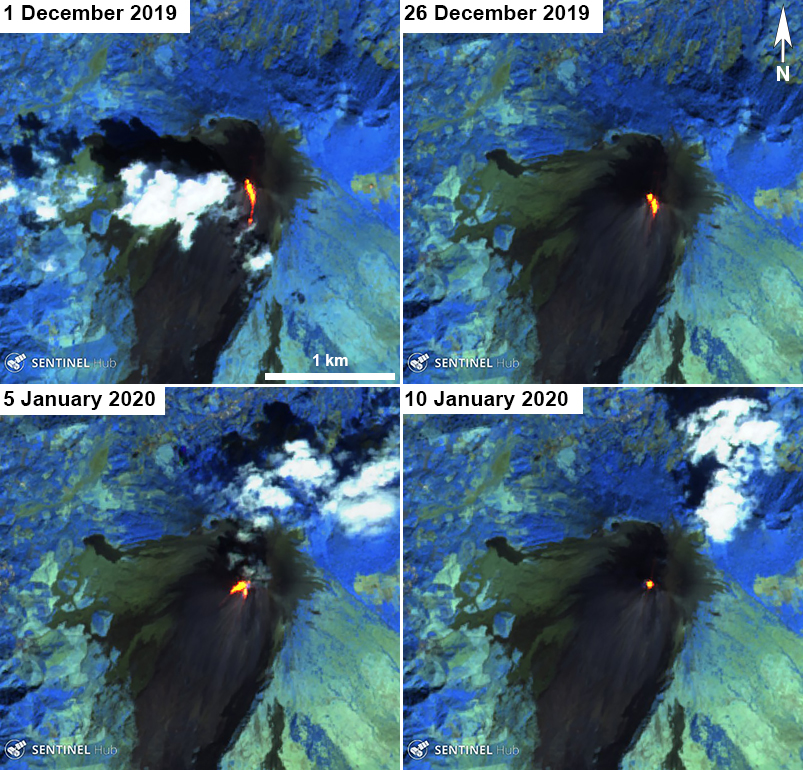

During December 2019, much of the activity remained the same, with Strombolian explosions originating from two emission points in the Mackenney crater ejecting material 75-100 m above the crater; white and occasionally blue gas-and-steam plumes to 100-300 m above the crater drifted up to 1.5 km downwind to the S and SW. Lava flows descended the S and SW flanks reaching 250-600 m long (figure 118). On 29 December seismicity increased, reaching 5,000 RSAM units.

|

Figure 118. Lava flows moving to the S and SW at Pacaya on 31 December 2019. Courtesy of INSIVUMEH (28 December 2019 to 3 January 2020 Weekly Report). |

Consistent Strombolian activity continued into January 2020 ejecting material 25-100 m above the crater. These explosions deposited material inside the Mackenney crater, contributing to the formation of a small cone. White and occasionally blue fumaroles consisting of mostly water vapor were observed drifting in different directions. At night, summit incandescence and lava flows were visible descending the N, NW, and S flanks with the flow on the NW flank traveling toward the Cerro Chino crater.

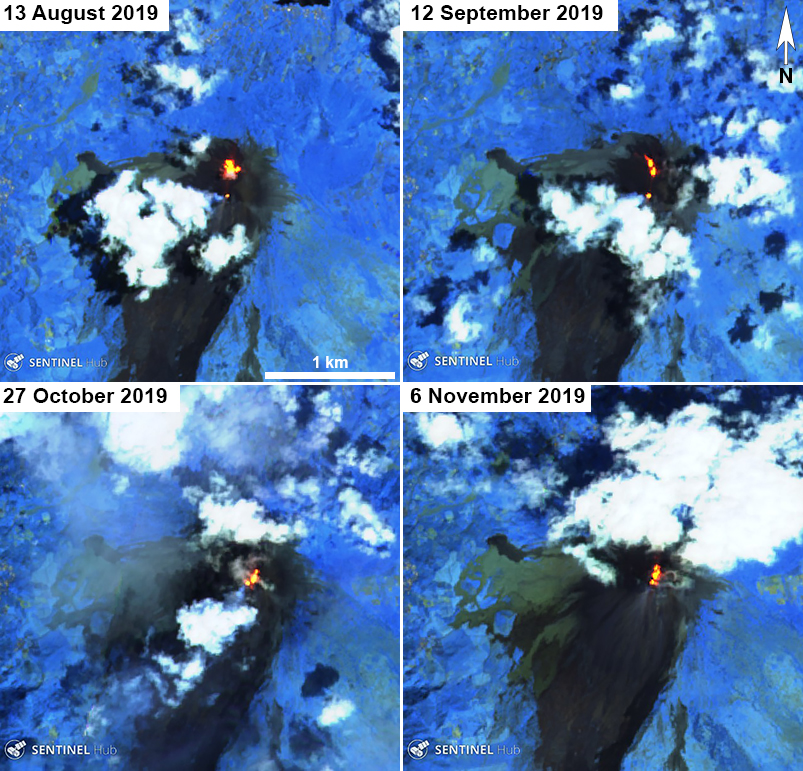

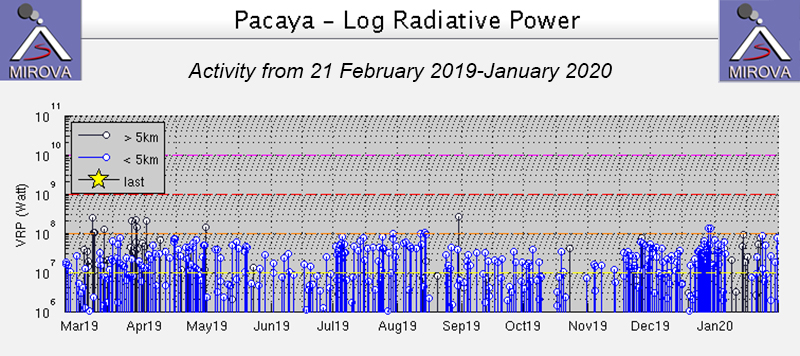

During August 2019 through January 2020, multiple lava flows and bright thermal anomalies (yellow-orange) within the crater were seen in Sentinel-2 thermal satellite imagery (figures 119 and 120). In addition, constant strong thermal anomalies were detected by the MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) system during 21 February 2019 through January 2020 within 5 km of the summit (figure 121). A slight decrease in energy was seen from May to June and August to September. Energy increased again between November and December. According to the MODVOLC algorithm, 37 thermal alerts were recorded during August 2019 through January 2020.

Geological Summary. Eruptions from Pacaya are frequently visible from Guatemala City, the nation's capital. This complex basaltic volcano was constructed just outside the southern topographic rim of the 14 x 16 km Pleistocene Amatitlán caldera. A cluster of dacitic lava domes occupies the southern caldera floor. The post-caldera Pacaya massif includes the older Pacaya Viejo and Cerro Grande stratovolcanoes and the currently active Mackenney stratovolcano. Collapse of Pacaya Viejo between 600 and 1,500 years ago produced a debris-avalanche deposit that extends 25 km onto the Pacific coastal plain and left an arcuate scarp inside which the modern Pacaya volcano (Mackenney cone) grew. The NW-flank Cerro Chino crater was last active in the 19th century. During the past several decades, activity has consisted of frequent Strombolian eruptions with intermittent lava flow extrusion that has partially filled in the caldera moat and covered the flanks of Mackenney cone, punctuated by occasional larger explosive eruptions that partially destroy the summit.

Information Contacts: Instituto Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanologia, Meteorologia e Hydrologia (INSIVUMEH), Unit of Volcanology, Geologic Department of Investigation and Services, 7a Av. 14-57, Zona 13, Guatemala City, Guatemala (URL: http://www.insivumeh.gob.gt/); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); Sentinel Hub Playground (URL: https://www.sentinel-hub.com/explore/sentinel-playground).