Report on Villarrica (Chile) — September 2020

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 45, no. 9 (September 2020)

Managing Editor: Edward Venzke.

Edited by A. Elizabeth Crafford.

Villarrica (Chile) Continued summit incandescence February-August 2020 with larger explosions in July and August

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 2020. Report on Villarrica (Chile) (Crafford, A.E., and Venzke, E., eds.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 45:9. Smithsonian Institution. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.BGVN202009-357120

Villarrica

Chile

39.42°S, 71.93°W; summit elev. 2847 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Historical eruptions at Chile's Villarrica, documented since 1558, have consisted largely of mild-to-moderate explosive activity with occasional lava effusion. An intermittently active lava lake at the summit has been the source of Strombolian activity, incandescent ejecta, and thermal anomalies for several decades; the current eruption has been ongoing since December 2014. Continuing activity during February-August 2020 is covered in this report, with information provided by the Southern Andes Volcano Observatory (Observatorio Volcanológico de Los Andes del Sur, OVDAS), part of Chile's National Service of Geology and Mining (Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería, SERNAGEOMIN), and Projecto Observación Villarrica Internet (POVI), part of the Fundacion Volcanes de Chile, a private research group that studies volcanoes across Chile. Sentinel satellite imagery also provided valuable data.

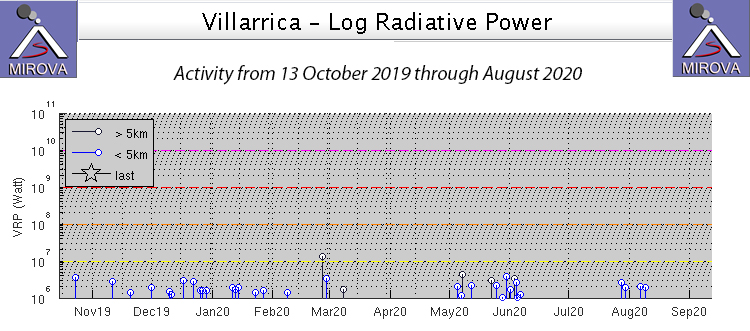

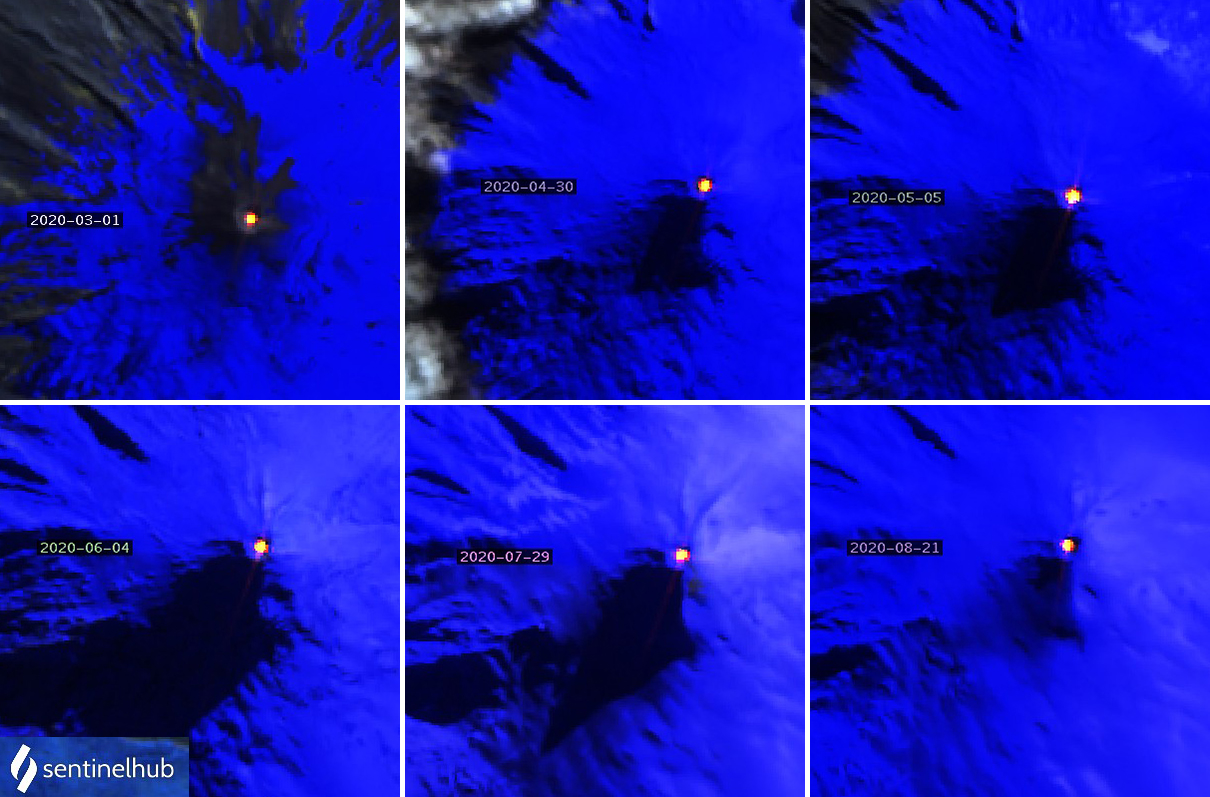

Intermittent incandescence was observed at the summit throughout February-August 2020, which was reflected in the MIROVA thermal anomaly data for the period (figure 92). Continuous steam and gas emissions with occasional ash plumes rose 100-520 m above the summit. Every clear satellite image of Villarrica from February -August 2020 showed either a strong thermal anomaly within the summit crater or a dense cloud within the crater that prevented the heat signal from being measured. Sentinel-2 captured on average twelve images of Villarrica each month (figure 93). Larger explosions on 25 July and 7 August produced ejecta and ash emissions.

Primarily white gas emissions rose up to 400 m above the summit during the first half of February 2020 and to 320 m during the second half. Incandescence was observed on clear nights. Incandescent ejecta was captured in the POVI webcam on 7 February (figure 94). Sentinel-2 satellite imagery showed bright thermal anomalies at the summit on 5, 8, 10, 13, 18, 20, 23, 25, and 28 February, nine of the eleven days that images were taken; the other days were cloudy.

|

Figure 94. Incandescent ejecta at the summit of Villarrica was captured in the POVI webcam late on 7 February 2020. Time sequence runs from top to bottom, then left to right. Courtesy of POVI. |

Villarrica remained at Alert Level Yellow (on a four-level Green-Yellow-Orange-Red scale) in March 2020. Plumes of gas rose 350 m above the crater during the first half of March. The POVI webcam captured incandescent ejecta on 1 March (figure 95). SERNAGEOMIN reported continuous white emissions and incandescence at night when the weather permitted. During the second half of March emissions rose 300 m above the crater; they were mostly white but occasionally gray and drifted N, S, and SE. Nighttime incandescence could be observed from communities that were tens of kilometers away on multiple occasions (figure 96). Sentinel-2 satellite imagery showed bright thermal anomalies at the summit on 1, 3, 4, 6, 9, 11, 14, 16, 19, 26, 29, and 31 March, twelve of the fourteen days images were taken. The other days were cloudy.

|

Figure 95. Incandescent ejecta rose from the summit of Villarrica in the early morning of 1 March 2020. Courtesy of POVI. |

|

Figure 96. Nighttime incandescence was observed on 24 March 2020 tens of kilometers away from Villarrica. Courtesy of Luis Orlando. |

During the first half of April 2020 plumes of gas rose 300 m above the crater, mostly as continuous degassing of steam. Incandescence continued to be seen on clear nights throughout the month. Steam plumes rose 150 m high during the second half of the month. A series of Strombolian explosions on 28-29 April ejected material up to 30 m above the crater rim (figure 97). Sentinel-2 satellite imagery showed bright thermal anomalies at the summit on 3, 8, 10, 13, 20, and 30 April, six of the twelve days images were taken; other days were cloudy.

|

Figure 97. A series of Strombolian explosions on 28-29 April 2020 at Villarrica ejected material up to 30 m above the crater rim. Courtesy of POVI. |

Daily plumes of steam rose 160 m above the summit crater during the first half of May 2020; incandescence was visible on clear nights throughout the month. During 5-7 May webcams captured episodes of dark gray emissions with minor ash that, according to SERNAGEOMIN, was related to collapses of the interior crater walls. Plumes rose as high as 360 m above the crater during the second half of May. The continuous degassing was gray and white with periodic ash emissions. Pyroclastic deposits were noted in a radius of 50 m around the crater rim associated with minor explosive activity from the lava lake. The POVI infrared camera captured a strong thermal signal rising from the summit on 29 May (figure 98), although no visual incandescence was reported. Residents of Coñaripe (17 km SSW) could see steam plumes at the snow-covered summit on 31 May (figure 99). Sentinel-2 satellite imagery showed bright thermal anomalies at the summit on 5, 13, 20, 23, 25 and 30 May, six of the twelve days images were taken. The other days were cloudy.

|

Figure 98. The POVI infrared camera captured a strong thermal signal rising from the summit of Villarrica on 29 May 2020; no visual incandescence was noted. Courtesy of POVI. |

|

Figure 99. Residents of Coñaripe (17 km SSW) could see steam plumes at the snow-covered summit of Villarrica on 31 May 2020. Courtesy of Laura Angarita. |

For most of the first half of June, white steam emissions rose as high as 480 m above the crater rim. A few times, emissions were gray, attributed to ash emissions from collapses of the inner wall of the crater by SERNAGEOMIN. Incandescence was visible on clear nights throughout the month. Vertical inflation of 1.5 cm was noted during the first half of June. Skies were cloudy for much of the second half of June; webcams only captured images of the summit on 21 and 27 June with 100-m-high steam plumes. Sentinel-2 satellite imagery showed bright thermal anomalies at the summit on 4, 7, and 14 June, three of the twelve days images were taken. The other days were cloudy.

Atmospheric clouds prevented most observations of the summit during the first half of July (figure 100); during brief periods it was possible to detect incandescence and emissions rising to 320 m above the crater. Continuous degassing was observed during the second half of July; the highest plume rose to 360 m above the crater on 23 July. On 25 July, monitoring stations in the vicinity of Villarrica registered a large-period (LP) seismic event associated with a moderate explosion at the crater. It was accompanied by a 14.7 Pa infrasound signal measured 1 km away. Meteorological conditions did not permit views of any surface activity that day, but a clear view of the summit on 28 July showed dark tephra on the snow around the summit crater (figure 101). Sentinel-2 satellite imagery showed bright thermal anomalies at the summit on 2 and 29 July, two of the twelve days images were taken. The other days were either cloudy or had steam obscuring the summit crater.

An explosion on 7 August at 1522 local time (1922 UTC) produced an LP seismic signal and a 10 Pa infrasound signal. Webcams were able to capture an image of the explosion which produced a dense plume of steam and ash that rose 370 m above the summit and drifted SE (figure 102). The highest plumes in the first half of August reached 520 m above the summit on 7 August. Sporadic emissions near the summit level were reported by the Buenos Aires VAAC the following day but were not observed in satellite imagery. When weather permitted during the second half of the month, continuous degassing to 200 m above the crater was visible on the webcams. SERNAGEOMIN participated in a webinar on 20 August 2020 discussing safety at Villarrica and showed an image of the summit crater taken during an overflight on 19 August (figure 103). Sentinel-2 satellite imagery showed bright thermal anomalies at the summit on 6, 21, and 31 August, three of the thirteen days images were taken. The other days were cloudy.

Geological Summary. The glacier-covered Villarrica stratovolcano, in the northern Lakes District of central Chile, is ~15 km south of the city of Pucon. A 2-km-wide caldera that formed about 3,500 years ago is located at the base of the presently active, dominantly basaltic to basaltic andesite cone at the NW margin of a 6-km-wide Pleistocene caldera. More than 30 scoria cones and fissure vents are present on the flanks. Plinian eruptions and pyroclastic flows that have extended up to 20 km from the volcano were produced during the Holocene. Lava flows up to 18 km long have issued from summit and flank vents. Eruptions documented since 1558 CE have consisted largely of mild-to-moderate explosive activity with occasional lava effusion. Glaciers cover 40 km2 of the volcano, and lahars have damaged towns on its flanks.

Information Contacts: Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería (SERNAGEOMIN), Observatorio Volcanológico de Los Andes del Sur (OVDAS), Avda Sta María No. 0104, Santiago, Chile (URL: http://www.sernageomin.cl/); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Sentinel Hub Playground (URL: https://www.sentinel-hub.com/explore/sentinel-playground); Proyecto Observación Villarrica Internet (POVI), (URL: http://www.povi.cl/, https://twitter.com/povi_cl/status/1237541250825248768); Luis Orlando (URL: https://twitter.com/valepizzas/status/1242657625495539712); Laura Angarita (URL: https://twitter.com/AngaritaV/status/1267275374947377152, https://twitter.com/AngaritaV/status/1288086614422573057); Geography Fans (URL: https://twitter.com/Geografia_Afic/status/1284520850499092480); Turismo Integral (URL: https://turismointegral.net/expertos-entregan-recomendaciones-por-actividad-registrada-en-volcan-villarrica/).