Report on Nevados de Chillan (Chile) — December 2022

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 47, no. 12 (December 2022)

Managing Editor: Edward Venzke.

Edited by Kadie L. Bennis.

Nevados de Chillan (Chile) Explosions, ash plumes, pyroclastic flows, and thermal activity during June-October 2022

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 2022. Report on Nevados de Chillan (Chile) (Bennis, K.L., and Venzke, E., eds.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 47:12. Smithsonian Institution.

Nevados de Chillan

Chile

36.868°S, 71.378°W; summit elev. 3180 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Nevados de Chillán, located in the Chilean Central Andes, has had multiple recorded eruptions dating back to the seventeenth century. The current eruption began in January 2016 with a phreatic explosion and ash emissions from the new Nicanor crater on the E flank of Nuevo crater. Recently, activity has consisted of pyroclastic flows, gas-and-ash plumes, and a new lava dome (Dome 4) that was detected during early March 2022 (BGVN 47:06). This report updates information during June through October 2022 that describes continued explosions, ash plumes, pyroclastic flows, and thermal activity, based on information from Chile's Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería (SERNAGEOMIN)-Observatorio Volcanológico de Los Andes del Sur (OVDAS) and satellite data.

During June through 17 October 2022 there was continuing eruptive activity in the Nicanor crater, which initially consisted of seismic events, sulfur dioxide emissions, and thermal anomalies (table 3). During August through mid-October, explosion events became more frequent and generated ash plumes that rose as high as 2.7 km above the crater. Explosions were also accompanied by pyroclastic flows that traveled no farther than 800 m down multiple flanks. Incandescent ejecta was visible above the crater rim in surveillance cameras, with some material falling back onto the proximal flanks.

Table 3. Summary of seismic events, maximum sulfur dioxide values, and number of thermal anomalies at Nevados de Chillán during June-October 2022. Data from SERNAGEOMIN bi-weekly reports.

| Month | Number of volcano-tectonic (VT) events | Number of long-period (LP) events | Number of explosion-related (EX) events | Number of tremor events (TR) | Daily maximum sulfur dioxide value | Number of days a thermal anomaly was detected in Sentinel-2 L2A images |

| Jun 2022 | 56 | 1,231 | 320 | 472 | 767 t/d | 5 |

| Jul 2022 | 67 | 1,416 | 212 | 454 | 1,056 t/d | 6 |

| Aug 2022 | 92 | 1,382 | 364 | 532 | 1,017 t/d | 8 |

| Sep 2022 | 180 | 1,200 | 237 | 332 | 870 t/d | 5 |

| Oct 2022 | 131 | 710 | 84 | 112 | 911 t/d | 3 |

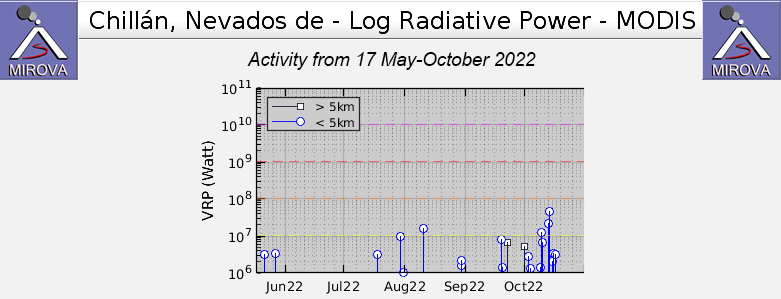

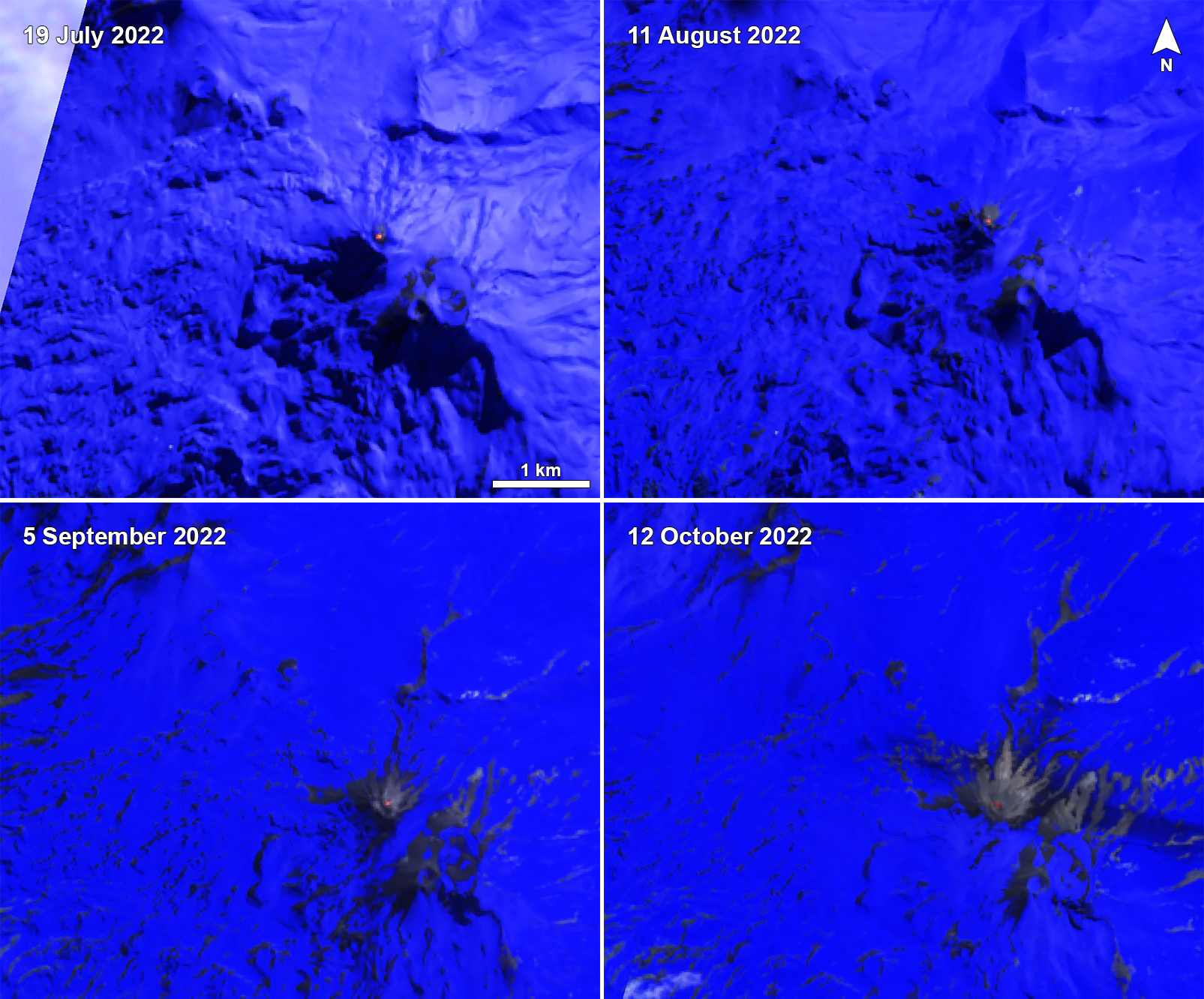

Low thermal activity was occasionally detected by satellite data during July through October, as shown in the MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) Log Radiative Power graph (figure 99). There was a small cluster of thermal activity that occurred during mid-September through early October, which occurred around the same time as strong explosive eruptions. A single thermal hotspot was detected on 13 October according to the MODVOLC thermal algorithm. Some of this activity was also reflected in Sentinel-2 infrared satellite imagery as a small thermal hotspot in the active Nicanor crater (figure 100).

Activity during June consisted of explosions that generated eruptive plumes with little to no pyroclastic content and crater incandescence that was visible up to 150 m above the crater; the highest plumes reached 940 m above the crater on 19 June. Seismicity was characterized by 56 volcano-tectonic (VT) events, 1,231 long-period (LP) events, and 472 tremor-type (TR) events. There were 320 LP-type events that were linked to surface-level explosions. Sulfur dioxide emission data was obtained by Differential Absorption Optical Spectroscopy (DOAS) equipment, which were installed on the SSE and ESE flanks of the active Nicanor crater. The average emission value ranged from 445 ± 95 to 453 ± 85 t/d, with a maximum daily value of 767 t/d recorded on 8 June. These sulfur dioxide levels are above base levels but are consistent with the presence of the new lava dome (Dome 4) that formed during early March 2022.

Explosive activity from the active crater continued during July and typically generated white gas-and-steam plumes less than 500 m high; due to weather clouds visibility was often obstructed. Seismicity included 67 VT-type events, 1,416 LP-type events, and 454 TR-type events. Of the 1,416 LP-type events, 212 were linked to surface-level explosions. On 13 July an explosion generated an avalanche mixed with deposits on the NE flank of the Nuevo crater that reached 470 m long. Ejecta traveled less than 200 m from the vent and were deposited on the E slope. On 29 July an eruptive episode produced a plume that rose 1,290 m above the crater. Explosions toward the end of the month also ejected a moderate amount of pyroclastic material less than 200 m from the vent onto the nearby flanks. DOAS data showed that the average sulfur dioxide emission value during the month ranged from 554 ± 29 to 601 ± 273 t/d. The maximum daily value was 1,056 t/d on 21 July.

During August, continuous explosions produced eruption plumes with little pyroclastic content that generally rose less than 500 m above the crater; on 2 and 20 August plumes exceeded 1 km above the crater. Intermittent night incandescence was visible to less than 50 m high and did not go beyond the crater rim. A total of 92 VT-type events, 1,382 LP-type events, and 532 TR-type events were detected throughout the month; of the LP-type events, 364 were linked to surface-level explosions. On 11 August surveillance cameras showed an extrusion of material inside the active crater, which SERNAGEOMIN reported was preceded by an increase in sulfur dioxide rates, plume heights associated with explosions, and increased explosion frequency. An explosion on 29 August generated a plume that rose 2 km above the crater and drifted S (figure 101). In addition, pyroclastic flows were reported, traveling less than 500 m on the E and NE flanks. The average sulfur dioxide emission value throughout the month ranged from 413 ± 69 to 507 ± 83 t/d, according to DOAS data. The maximum daily value was 1,017 t/d on 9 August. There was a slight decrease in sulfur dioxide emission rates toward the end of the month.

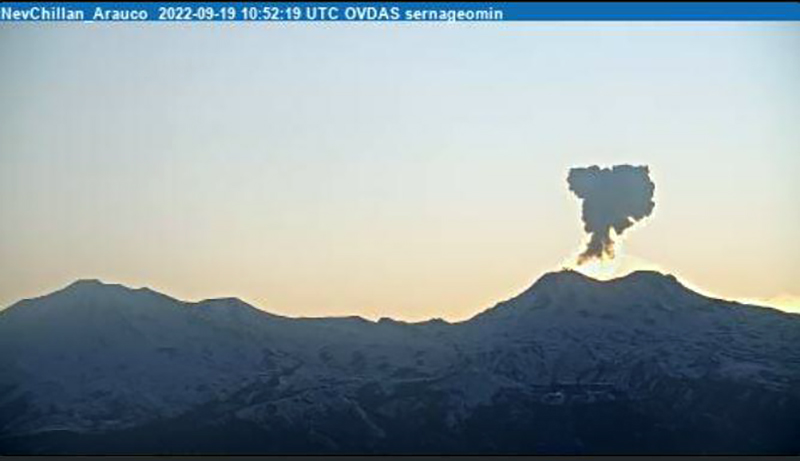

Three surveillance cameras continued to detect explosions and eruption plumes composed of mostly gas-and-steam that rose between 500-1,000 m above the crater during September. Seismicity consisted of 180 LP-type events, 1,200 LP-type events, and 332 TR-type events; of the LP-type events, 237 events were linked to surface-level explosions. On 12 September a strong explosion generated an eruption plume that rose 1.4 km above the crater. Toward the end of the month, the explosive events contained a higher volume of pyroclastic content, according to SERNAGEOMIN; ejecta was dispersed SE and block avalanches traveled as far as 500 from the crater rim. On 16, 19, and 30 September explosions produced plumes that carried a higher volume of pyroclastic material more than 360 m above the crater. Two explosions were reported on 19 September: the first rose 1.1 km above the crater and drifted SE (figure 102). A block avalanche occurred on the W flank that traveled 500 m from the crater rim. The second explosion produced an incandescent eruptive column that rose 1.7 km above the crater and drifted SE; ashfall was visible to the SE and ejecta was reported on the W flank. According to SERNAGEOMIN, these explosions also partially destroyed Dome 4. DOAS data recorded that sulfur dioxide emission rates during the month ranged from 315 ± 85 to 323 ± 76 t/d; the maximum daily value was 870 t/d on 12 September.

More frequent explosions and incandescent material were reported during early October, based on surveillance camera data. Six explosions generated plumes that rose more than 1 km above the crater and three exceeded 2 km. Seismicity has been characterized by 131 VT-type events, 710 LP-type events, and 122 TR-type events. There were 84 LP-type events that were linked to surface-level explosions. Explosions on 2 and 13 October were accompanied by 300-m-long pyroclastic flows and ejecta that traveled more than 500 m from the crater. A strong explosion on 9 October generated an eruption plume that rose 2.4 km above the crater and drifted NNW (figure 103); ashfall was reported in the same direction. In addition, pyroclastic flows were observed on the N, NNE, NE, and E flanks and traveled as far as 766 m. The flows mixed with snow on the volcano, which resulted in avalanche-type flows that moved 1.3 km down the N and NE flanks. Incandescent ejecta was visible at least as high as 800 m above the crater on 15 October. On 16 and 17 October there were three high-energy explosions; on 17 October the eruption column rose 2.7 km above the crater. During this explosion, pyroclastic flows were generated along the N, NW, W, NE, and E flanks and reached as far as 780 m on the NE flank. Some of these flows interacted with snow on the volcano and produced an avalanche-type flow that reached up to 2 km on the NE flank. DOAS measurements showed that the sulfur dioxide emission rates ranged from 47 ± 18 to 284 ± 83 t/d, with a maximum daily value of 911 t/d on 12 October. After the event on 17 October, there was an abrupt drop in surface activity with no eruptive columns or crater incandescence observed.

Geological Summary. The compound volcano of Nevados de Chillán is one of the most active of the Central Andes. Three late-Pleistocene to Holocene stratovolcanoes were constructed along a NNW-SSE line within three nested Pleistocene calderas, which produced ignimbrite sheets extending more than 100 km into the Central Depression of Chile. The dominantly andesitic Cerro Blanco (Volcán Nevado) stratovolcano is located at the NW end of the massif. Volcán Viejo (Volcán Chillán), which was the main active vent during the 17th-19th centuries, occupies the SE end. The Volcán Nuevo lava-dome complex formed during 1906-1945 on the NW flank of Viejo. The Volcán Arrau dome complex was then constructed on the SE side of Volcán Nuevo between 1973 and 1986, and eventually exceeded its height. Smaller domes or cones are present in the 5-km valley between the two major edifices.

Information Contacts: Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería (SERNAGEOMIN), Observatorio Volcanológico de Los Andes del Sur (OVDAS), Avda Sta María No. 0104, Santiago, Chile (URL: http://www.sernageomin.cl/, https://twitter.com/Sernageomin); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); Sentinel Hub Playground (URL: https://www.sentinel-hub.com/explore/sentinel-playground).