Report on Fuego (Guatemala) — August 2018

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 43, no. 8 (August 2018)

Managing Editor: Edward Venzke.

Edited by A. Elizabeth Crafford.

Fuego (Guatemala) Pyroclastic flows on 3 June 2018 cause at least 110 fatalities, 197 missing, and extensive damage; ongoing ash explosions, pyroclastic flows, and lahars

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 2018. Report on Fuego (Guatemala) (Crafford, A.E., and Venzke, E., eds.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 43:8. Smithsonian Institution. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.BGVN201808-342090

Fuego

Guatemala

14.4748°N, 90.8806°W; summit elev. 3799 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Guatemala's Volcán de Fuego was continuously active throughout the first half of 2018; it has been erupting vigorously since 2002 with historical observations of eruptions dating back to 1531. These eruptions have resulted in major ashfalls, pyroclastic flows, lava flows, and damaging lahars. Large explosions with a significant number of fatalities occurred during 3-5 June 2018 and are covered in this report of activity from January-June 2018. Reports are provided by the Instituto Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanología, Meteorología e Hidrologia (INSIVUMEH) and the National Office of Disaster Management (CONRED); aviation alerts of ash plumes are issued by the Washington Volcanic Ash Advisory Center (VAAC). Satellite data from NASA, NOAA, and other sources provide valuable information about heat flow and gas emissions. Numerous media outlets provided photographs of the eruptive activity.

Summary of activity, January-June 2018. The first eruptive event of 2018 occurred during 31 January-1 February and lasted for about 20 hours. It included pyroclastic flows, lava flows, incandescent ejecta, ash plumes that rose to 7 km altitude, and ashfall more than 60 km from the volcano. Four lava flows emerged during the event, and the longest traveled 1,500 m down the Seca ravine. Multiple daily explosions that generated ash plumes continued through May 2018. Ash plumes usually rose to 4.2-4.9 km altitude (400-1,200 m above the summit) and drifted up to about 15 km from the volcano in the prevailing wind directions. Ashfall was often reported from communities within 10 km of the summit, most commonly to the W and SW, but also occasionally to the N and NE. Incandescent ejecta rose up to 300 m above the summit during periods of increased activity; block avalanches of the incandescent material descended the major drainages on all flanks, often as far as the vegetated areas several hundred m below the summit.

The first lahar of the year was reported on 9 April; additional lahars occurred several times during May after rainy periods. They were generally 20-30 m wide and 1-2 m deep, carrying debris 1-2 m in diameter. A lava flow was active in the Ceniza ravine for the second half of May, moving up to 1,000 m from the summit during heightened activity on 22 May, and again on 2 June.

The second major eruptive event of 2018, and the largest and deadliest explosive activity in recent history at Fuego, began with a strong explosion on the morning of 3 June 2018. Multiple explosions throughout the day produced an ash plume that was observed in satellite data at 15.2 km altitude, and a strong SO2 plume that drifted N and NE. Numerous large pyroclastic flows generated by the explosions throughout the day descended multiple ravines around the flanks. The most heavily damaged communities were San Miguel Los Lotes and El Rodeo, 10 km SE of the summit at the base of Las Lajas ravine. Most infrastructure in the communities was buried in ash; there were 110 reported fatalities, and at least 197 people reported missing and presumed dead. Additional explosions two days later caused a brief halt in recovery efforts as more pyroclastic flows covered the same area.

Abundant rainfall that began on 6 June 2018 led to over 30 lahars throughout the rest of the month, inundating all of the major ravines and tributaries of the Rio Pantaleón and Rio Gobernador and causing additional infrastructure damage to bridges and roads. The lahars were often 30-40 m wide, 3 m deep, and carried volcanic blocks and debris up to 3 m in diameter. Explosive activity declined to background levels by the middle of June, but daily explosions with ash plumes and incandescent avalanche blocks continued for the remainder of the month, with continued reports of ashfall in communities within 15 km of the summit.

Activity during January-February 2018. During January 2018, plumes of steam rose to 4.3-4.5 km altitude, drifting primarily W, SW, and S. Activity included 3 to 8 explosions per hour that generated ash plumes, which rose to about 4.3-4.8 km altitude (figure 82). Explosions on 19 January increased to 7-13 per hour, and produced ash plumes that drifted more than 15 km W, SW, and S. Incandescent ejecta rose 100-300 m above the crater and traveled up to 400 m from the crater, in some cases reaching vegetated areas. The SW flank was the most affected by ashfall; it was reported in the communities of San Pedro Yepocapa, Escuintla, Sangre de Cristo, Finca Palo Verde, El Porvenir, Santa Sofía, Morelia, Paniché I and II, Rochela, and Ceilán. Block avalanches traveled down the Seca, Taniluyá, Cenizas and Las Lajas ravines. On 28 January, seismic station FG3 registered an increase in pulses of tremor activity. MODVOLC thermal alerts were issued during 17 days in January. The Washington VAAC issued multiple daily aviation alerts on 22 days of the month.

The first major eruptive event of 2018 occurred during 31 January-1 February and lasted for about 20 hours. It included pyroclastic flows, lava flows, incandescent ejecta, ash plumes that rose to 7 km altitude, and ashfall more than 60 km W, SW, and NE from the volcano (figure 83). Explosive activity increased to 5-8 events per hour, incandescent material rose up to 300 m above the crater, and ejecta traveled 300 m.

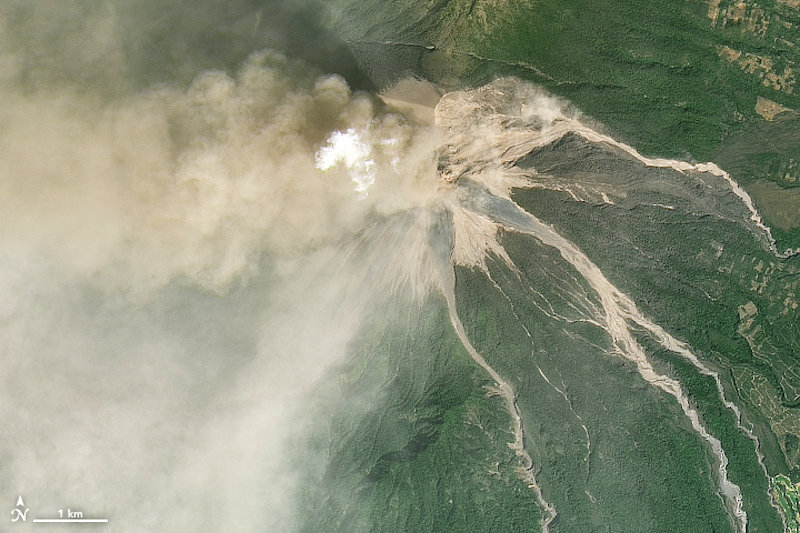

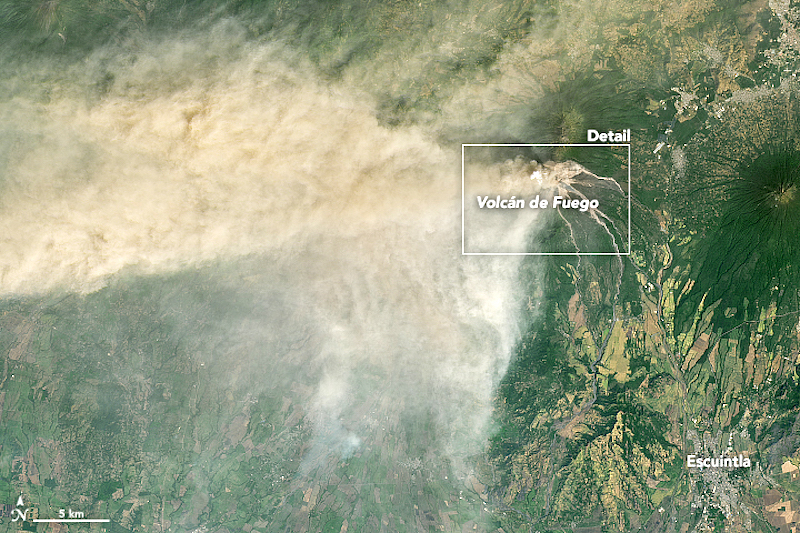

The substantial ash plume produced from the event drifted tens of kilometers to the W and SW (figures 84 and 85). The SW flank was the area most affected by ashfall, where communities of San Pedro Yepocapa and Escuintla, Sangre de Cristo, Palo Verde, El Porvenir, Santa Sofia, Morelia, Paniché I and II are located. Ashfall also occurred 10-25 km NE in La Rochela, San Andrés Osuna, La Reina, Ciudad Vieja, Antigua Guatemala, and in the WSW part of Guatemala City.

|

Figure 84. A dense ash plume drifts W and SW from Fuego on 1 February 2018. Image taken by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8. Courtesy of NASA Earth Observatory. |

Four lava flows emerged during the eruptive event; a 1,500-m-long flow traveled down the Seca ravine, a 700-m-long flow traveled down the Ceniza ravine, and flows in Las Lajas and La Honda canyons traveled 800 m from the summit. Numerous pyroclastic flows also descended the Honda and Seca ravines, and smaller pyroclastic flows descended the Trinidad and Las Lajas ravines (figure 86).

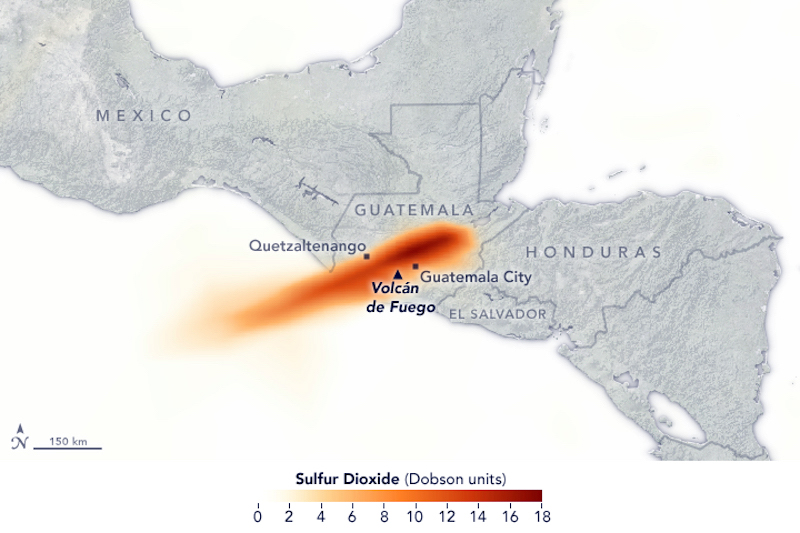

La Honda ravine had not been affected by pyroclastic flows since 1974; they traveled 5.8 km down that ravine (figure 87), and 4.2 km down the Seca ravine. About 2,880 residents of Escuintla (20 km SE) and Alotenango (8 km E) were evacuated during these events. Significant concentrations of SO2 were detected on 1 February by the Ozone Mapper Profiler Suite (OMPS) on the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (Suomi-NPP) satellite (figure 88).

Multiple daily explosions with ash plumes continued throughout the rest of February; plumes generally rose to 4.5-4.7 km altitude, and ashfall was reported in communities 10-20 km from the volcano in various directions. Block avalanches descended barrancas Seca, Taniluyá, and Ceniza on most days. Incandescence at night was visible up to 200 m above the crater. MODVOLC thermal alerts were issued on 8 days of the month, and the Washington VAAC issued multiple daily aviation alerts throughout the month.

Activity during March-May 2018. Constant activity continued during March and April 2018, without any major eruptive episodes. Continuous degassing, explosions with ash plumes (figure 89), incandescent ejecta, and daily block avalanches were reported. Steam plumes rose daily to 4.2-4.4 km altitude and usually drifted NW, W, SW, or S. Explosions averaged 4-9 per hour and produced ash plumes that rose to 4.3-4.8 km altitude drifting more than 20 km NW, W, SW, and S. Incandescent ejecta was measured up to 300 m above the crater and traveled a similar distance down the flanks. Block avalanches sent debris up to a kilometer down the major drainages most days. The MODVOLC system recorded thermal alerts during 20 days of March and 22 days of April. The communities most affected by near-daily ashfall, on the SW flank, included San Pedro Yepocapa and Escuintla, Sangre de Cristo, Palo Verde Estate, El Porvenir, Santa Sofia, Morelia, and Paniché I and II. The Washington VAAC issued multiple daily aviation alerts nearly every day during both months.

On 9 April the first lahar of the year descended the Seca canyon and the El Mineral channel, tributaries of the Pantaleón River. It was 10 m wide and 1.5 m deep, carrying abundant debris. In special bulletins released on 14 and 16 April INSIVUMEH noted increased explosive activity occurring at a rate of up to 10 explosions per hour, with ash plumes that rose to 4.8 km altitude. This was followed by a report of a lava flow during the evening of 16 April that traveled 1,300 m down the Seca Ravine.

Activity during the first two weeks of May 2018 was similar in character to the previous two months. Steam plumes rose to 4.1-4.3 km altitude, ash plumes rose to 4.5-4.8 km altitude from explosions that occurred at a rate of 4-8 per hour and drifted SW and W, and ashfall was reported in San Pedro Yepocapa, Morelia, El Por-venir, Sangre de Cristo, Santa Sofía, Finca Palo Verde, Panimaché I y II and other nearby communities. Incandescent ejecta rose 150-300 m high and was thrown 50 m from the crater; shockwaves from the explosions were felt 20-25 km away.

A lahar 12 m wide and 1.5 m deep descended the Seca Ravine on 10 May, dragging tree trunks and volcanic blocks as large as 1.5 m in diameter. A 500-m-long lava flow was reported in the barranca Ceniza on the afternoon of 15 May. Explosions occurred at a rate of 5-7 per hour on 16 May, and ash plumes rose as high as 7.8 km altitude and drifted 20 km W and SW, causing ashfall in Panimaché and Morelia. A moderate-sized lahar traveled down the El Jute ravine on 16 May after rains the previous night. During the afternoons of 16, 17, and 18 May lahars flowed down the Seca ravine from the recent abundant rainfall; they were 20 m wide, 1-2 m deep, and carried tree trunks and blocks 1-2 m in diameter. They grew to 25-30 m wide as they reached the confluence with the Rio Pantaleón, and the odor of sulfur was reported.

A lava flow in the barranca Ceniza was active for a distance of 900 m on 17 May, 600 m on 18 May, and 150 m on 19 May. Occasional sounds were audible more than 30 km from Fuego on 20 May from the 6-8 explosions that occurred every hour. Incandescent pulses rose 250 m above the crater during the night. The lava flow was active again to 700-800 m down the Ceniza ravine on 21 May. Overall activity increased to 10-15 weak to moderate explosions per hour on 22 May. The ash plumes rose to 4.3-4.7 km altitude and drifted 15 km S. Incandescent ejecta rose 300 m above the crater and lava flowed 1,000 m down the Ceniza ravine. On 23 May pulses of incandescent material rose 200-350 m above the crater and generated block avalanches that traveled down the Seca, Ceniza, and Las Lajas ravines as far as the vegetated areas. The lava flow in the Ceniza ravine was active up to 800 m from the summit that day. Explosions had decreased to 5-7 per hour by 24 May; the lava flow was still active 800 m down the Ceniza on 25 May.

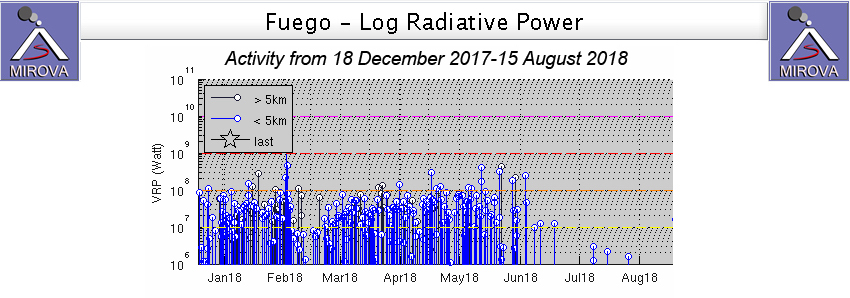

The Fuego Observatory reported lahars on 25 May in the Seca and Mineral ravines that were 35 m wide and 1.5 m deep carrying abundant volcanic material. They blocked access between the communities of Yepocapa and Morelia, Santa Sofia, and others on the SW flank. Weak explosions and incandescence continued during the last week of the month, with low-level ash plumes drifting generally S, although poor visibility obscured most observations. Ash advisory reports from the Washington VAAC were more intermittent during May than the previous few months, with reports issued on 13 days of the month. The MODVOLC system reported thermal alerts on 16 days during May. The MIROVA project Log Radiative Power plot for the first six months of 2018 showed constant levels of activity similar to that during 2017 (see figure 73, BGVN 43:02) through the beginning of June, with a spike during the eruptive episode of 31 January-1 February (figure 90). The thermal signal ceased abruptly after the explosive events of early June.

Fuego was characterized by ongoing moderate activity during the first two days of June. Steam plumes rose to 4.5 km altitude and drifted S, and 5-8 moderate explosions per hour produced ash plumes that rose to 4.6-4.8 km altitude and drifted 8-20 km S and SE. Moderate to strong shock waves from the explosions caused roofs to vibrate 15-20 km away on the S flank. Pulses of incandescent ejecta rose 100-200 m above the crater and created block avalanches that descended the Seca, Ceniza and Las Lajas ravines as far as the vegetated areas; fine-grained ash fell in Panamiche I. On 2 June lahars descended the Seca, Rio Mineral, Cenizas, Trinidad and Jute ravines, and a lava flow was reported moving 1,000 m down the Ceniza ravine.

Eruptive events of 3-5 June 2018. The second major eruptive event of 2018, and the deadliest in the recent history of Fuego, began with a strong explosion in the early morning of 3 June 2018. The ash plume rose rapidly to 6 km altitude and initially drifted W and SW. It generated large pyroclastic flows that traveled down the Seca, Santa Teresa, and Ceniza ravines and into the communities of Sangre de Cristo and San Pedro Yepocapa on the W flank. Strong explosions continued throughout the day and generated additional large pyroclastic flows in the Seca, Cenizas, Mineral, Taniluyá, Las Lajas, and Honda ravines with devastating consequences to numerous communities around the volcano (figures 91-94).

|

Figure 92. A large pyroclastic flow on 3 June 2018 descended the Las Lajas ravine adjacent to La Reunión Golf Course, 7 km SE of the summit of Fuego. Courtesy of Matthew Watson, volcanologist. |

|

Figure 93. The pyroclastic flows at Fuego on 3 June 2018 descended multiple ravines and damaged or destroyed a number of roadways and bridges. Photo Credit: AFP/Getty, courtesy of The Express. |

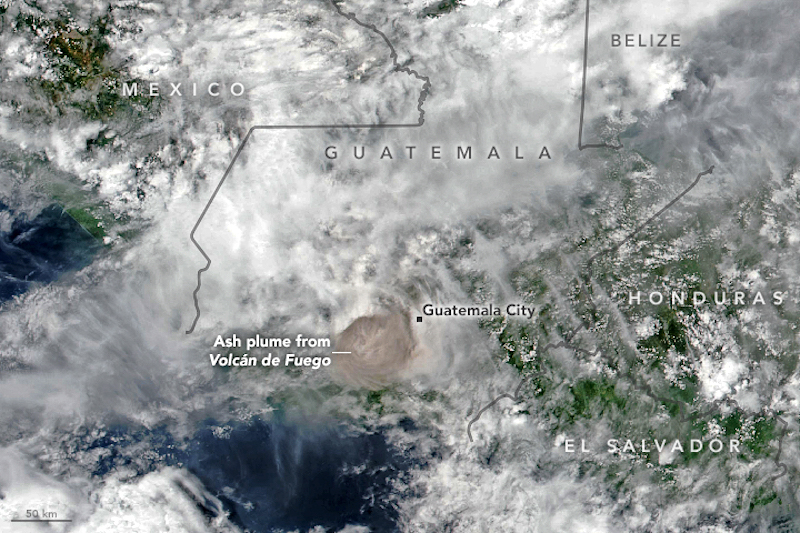

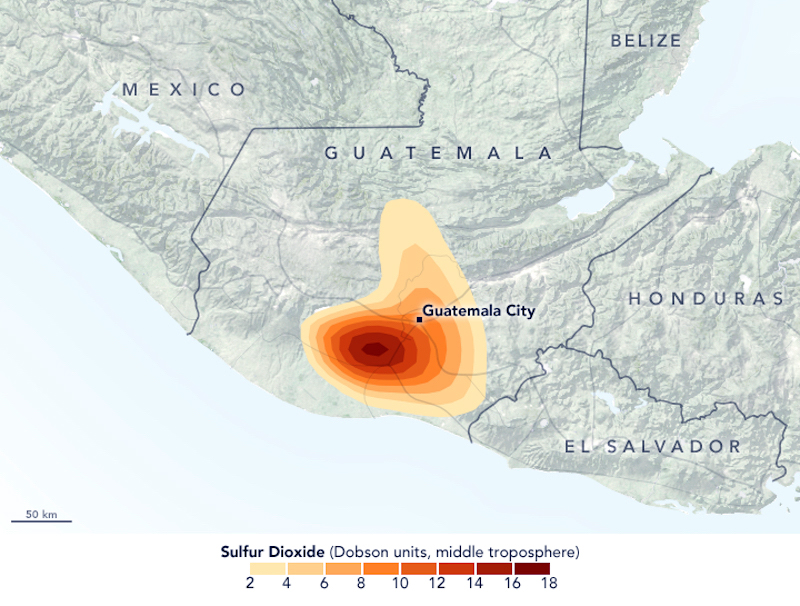

The Washington VAAC reported explosions later in the day that generated an ash plume that drifted NE at 9.1 km altitude and E at 15.2 km altitude. The Suomi NPP satellite captured an image of the ash plume rising above the cloud cover at 1300 local time (figure 95). Ashfall of tephra and lapilli was reported more than 25 km away in the village of La Soledad; in addition, the municipalities of Quisache (8 km NW), Acatenango (12 km NW), San Miguel Dueñas (10 km NE), Alotenango (8 km ENE), Antigua Guatemala (18 km NE), Chimaltenango (22 km N), and other areas NW and N of the volcano were impacted with ashfall. La Aurora airport in Guatemala City was closed for two days. In addition to the ash plume, a large plume of SO2 was recorded drifting N and E from the volcano at an altitude of 8 km shortly after the explosions were reported (figure 96).

The pyroclastic flows down the SE flank were especially devastating to the communities in their path, covering roofs and vehicles with ash and debris (figure 97-100) and killing scores of people. The communities of San Miguel Los Lotes about 9 km SE of the summit and El Rodeo (10 km SE), both in Escuintla Province, were severely damaged from the pyroclastic flows, with most of the fatalities and missing people reported from those communities.

Explosions continued until early evening on 3 June, when pyroclastic flow activity finally diminished. The debris from the pyroclastic flows resulted in lahars descending the Pantaleón, Mineral, and other drainages, leading to the evacuations of the communities of Sangre de Cristo, Finca Palo Verde, Panimache and others that evening. Explosive activity returned to lower levels the following day with dense ash plumes rising to 4.5-4.6 km altitude from 5-7 weak explosions that occurred every hour. Abundant fine ash rose from the ravines filled with pyroclastic flow material from the previous day and drifted SW, W, NW, and N, affecting communities up to 25 km away in those directions. The Washington VAAC reported remnants of the ash plume drifting 300 km ENE on 4 June.

By 4 June, CONRED had increased the Alert Level to red for the communities of Escuintla (22 km SE), Alotenango (8 km E), Sacatepéquez, Yepocapa (8 km NW), Santa Lucía Cotzumalguapa (22 km SW), and Chimaltenango, and opened 13 evacuation shelters in the area. CONRED initially reported on 5 June that 3,271 people were evacuated, 46 were injured and there were 70 known fatalities as a result of the pyroclastic flows and lahars on 3 June. A state of emergency was declared in all three of the provinces (Departments) of Escuintla, Sacatepéquez and Chimaltenango surrounding the volcano.

The number of block avalanches increased on 5 June as a result of 8-10 moderate explosions per hour; ash plumes and pyroclastic flow debris created persistent ash in the air around the volcano. The avalanches traveled 800-1,000 m down Las Lajas and Santa Teresa ravines. On 5 June, a pyroclastic flow descended the El Jute and Las Lajas ravines at 1410 local time. INSIVUMEH reported an increase in explosive activity a few hours later; dense ash plumes rose to 6 km altitude and drifted E and NE. Another pyroclastic flow descended the Las Lajas around 1928 local time that evening. These new pyroclastic flows led CONRAD to evacuate the additional communities of La Reyna, El Rodeo, Cañaveral I and IV, Hunnapu, Magnolia, and Sarita located on the Palín-Escuintla highway, and the highway itself was also closed (figure 102).

Activity during 6-30 June 2018. Weak to moderate explosions continued at Fuego on 6 June with ash plumes rising to 4.7 km altitude and drifting W and SW. Significant rainfall in the area that afternoon around 1610 resulted in lahars descending the Seca and Mineral ravines, tributaries of the Rio Pantaleón. One lahar was 30-40 m wide and 4-5 m deep emanating warm sulfurous gases; it carried fine-grained material similar to cement, rocks and debris 2-3 m in diameter, and tree trunks. The communities around the mouths of the ravines and near the Pantaleón Bridge were most affected. New lahars about an hour later descended the Santa Teresa, Mineral and Taniluyá ravines, also tributaries of the Pantaleón River. These lahars were about 30 m wide, 2-3 m deep, and carried similar cement-like fine grained material down the Pantaleón along with blocks 2-3 m in diameter and tree trunks.

Seismic station FG3 recorded a pyroclastic flow descending Las Lajas and El Jute ravines at 2140 local time on 7 June. INSIVUMEH estimated that it produced an ash cloud that rose to 6 km altitude and drifted W and SW. INSIVUMEH issued five special bulletins on 8 June reporting numerous lahars and pyroclastic flows. Lahars descended Santa Teresa, Mineral, and Taniluyá ravines into the Pantaleón around 0240 local time; they were 30 m wide, 2-3 m deep, and carried 2-3-m-diameter blocks and tree trunks. Another surge of lahars registered on the seismogram about two hours later in the same ravines and also in the Ceniza, additionally affecting the Achiguate River. A pyroclastic flow descended Las Lajas ravine at 0820 in the morning, producing another 6-km-high ash cloud. Two more similar pyroclastic flows in the same area were recorded at the seismic station at 1945 and 2040 local time that evening.

During the afternoon of 9 June, lahars descended the Seca, Mineral, Niagara and Taniluyá, generating the largest lahar to date for the year in the Pantaleón River. It was 40 m wide and 5 m deep carrying abundant blocks up to 3 m in diameter and other debris down the W flank. Later that evening explosive activity continued at a rate of 4-7 per hour, dispersing ash plumes up to 15 km W and SW from the summit at an altitude of 4.2-4.4 km. The explosions were audible up to 10 km in all directions. The same ravines and also the Ceniza were affected by new lahars 35 m wide and 3 m deep the following afternoon as a result of the constant rains in the area. Rains continued on 11 June and resulted in strong lahars descending the Seca and Mineral ravines around 1415 local time with diameters of 35-40 m and depths of 3 m. Another strong lahar descended Las Lajas and el Jute ravines in the evening at 1750 local time; these had widths ranging from 35-55 m and depths up to 5 m.

INSIVUMEH reported an increase in explosive activity beginning in the morning of 12 June 2018, producing ash plumes that rose up to 5 km altitude and drifted NE and N 15-25 km. This activity also produced a pyroclastic flow down the Seca ravine around 0730 local time with an ash cloud that rose about 6 km and drifted N and NE. That afternoon a strong lahar descended the Las Lajas ravine, carrying blocks 3 m in diameter in a hot, thick flow that was 35-45 m wide and up to 5 m deep. Since there were no longer distinct channels in the ravine, the material spread out in a wide fan flowing towards the area around El Rodeo. Additional smaller lahars descended the Ceniza and Mineral ravines later that afternoon. By 12 June 2018 CONRED reported that 110 fatalities had been confirmed, 197 additional people were missing, and over 12,500 people had been evacuated since the 3 June explosions began.

On 13 June, a small pyroclastic flow descended the Ceniza ravine around 0630. It was the last pyroclastic flow reported during June. Beginning with the first post-eruption lahars on 6 June, multiple lahars occurred every day during 8-18, 20-23, 26, and 30 June (table 18). The barrancas of Seca, Mineral, Santa Teresa, Taniluyá, Niagra, Ceniza, Las Lajas, El Jute, Rio El Gobernador, and Rio Pantaleón were all impacted by the lahars; they ranged in size from smaller flows that were 20 m wide and 2 m deep carrying blocks 1-3 m in diameter to the largest which were over 40 m wide, up to 5 m deep and carried blocks as large as 3 m in diameter. The flows were warm or hot, carrying tree trunks and other debris, and had strong sulfurous odors. Communities adjacent to the ravines could feel the vibrations of the flows as they passed. As many of the ravines were full of ash and rocks from the pyroclastic flows, new channels were formed and the flows spread out in fans as they descended, further threatening the communities around the flanks of the volcano.

Table 18. Lahars at Fuego were reported 33 separate times between 6 and 30 June 2018; many reports included multiple simultaneous lahars in drainages around all the flanks. Data courtesy of INSIVUMEH.

| Date | Local time | Ravine(s) | Width (m) | Depth (m) | Block Size (m) |

| 06 Jun 2018 | 1610 | Seca, Mineral | 30-40 | 4-5 | 2-3 |

| 06 Jun 2018 | 1720 | Santa Teresa, Mineral and Taniluyá | 30 | 2-3 | 2-3 |

| 08 Jun 2018 | 0240 | Santa Teresa, Mineral, and Taniluyá | 30 | 2-3 | 2-3 |

| 08 Jun 2018 | 0450 | Santa Teresa, Mineral, and Taniluyá, Ceniza | -- | -- | 2-3 |

| 09 Jun 2018 | 1400 | Seca, Mineral, Niagara and Taniluyá | 40 | 5 | 3 |

| 10 Jun 2018 | 1515 | Seca, Mineral, Niagara and Taniluyá, Ceniza | 35 | 3 | 1 |

| 11 Jun 2018 | 1415 | Seca and Mineral | 35-40 | 3 | 3 |

| 11 Jun 2018 | 1750 | Las Lajas and el Jute | 35-55 | 3-5 | 3 |

| 12 Jun 2018 | 1330 | Las Lajas | 35-45 | 5 | 3 |

| 12 Jun 2018 | 1425 | Ceniza, Mineral | 20 | 2 | 1-3 |

| 13 Jun 2018 | 0110 | Ceniza | 25 | 2 | 1-3 |

| 13 Jun 2018 | 1350 | Las Lajas | 30-40 | 3 | 3 |

| 14 Jun 2018 | 0145 | Santa Teresa and Mineral | 20-25 | 2 | 3 |

| 14 Jun 2018 | 1445 | Taniluyá, Ceniza, rio El Gobernador, Las Lajas | 30-45 | 3 | 3 |

| 15 Jun 2018 | 1715 | Seca, Mineral | 30-35 | 3 | 3 |

| 15 Jun 2018 | 1725 | Las Lajas | 30-35 | 2 | 3 |

| 15 Jun 2018 | 1740 | Taniluyá, Ceniza | 20-25 | 2 | 3 |

| 16 Jun 2018 | 1445 | Las Lajas | 30-35 | 2 | 3 |

| 17 Jun 2018 | 1415 | Las Lajas | -- | -- | 3 |

| 17 Jun 2018 | 1440 | Seca, Mineral | 40 | 2 | 2 |

| 18 Jun 2018 | 1510 | Seca, Mineral | 25-30 | 3 | 3 |

| 18 Jun 2018 | 1600 | Las Lajas | 40-45 | 2 | 3 |

| 20 Jun 2018 | 0735 | Las Lajas | 35-45 | 2-3 | 3 |

| 20 Jun 2018 | 1230 | Las Lajas | 30-35 | 3 | 3 |

| 20 Jun 2018 | 1415 | Seca, Mineral, Taniluyá, Ceniza | 30-35 | 3 | 3 |

| 21 Jun 2018 | 1940 | Las Lajas | 30-35 | 3 | 3 |

| 22 Jun 2018 | 0030 | Las Lajas | -- | -- | 3 |

| 22 Jun 2018 | 1450 | Las Lajas | -- | -- | 2-3 |

| 22 Jun 2018 | 1535 | Rio Pantaleón | 40 | 3 | 3 |

| 23 Jun 2018 | 1740 | El Jute, Las Lajas, San Miguel los Lotes area | -- | -- | 3 |

| 26 Jun 2018 | 1412 | El Jute, Las Lajas, San Miguel los Lotes area | -- | -- | 3 |

| 26 Jun 2018 | 1455 | Seca, Mineral, Niagra, Ceniza | -- | -- | 2-3 |

| 30 Jun 2018 | 1435 | Seca, Mineral | -- | -- | 2-3 |

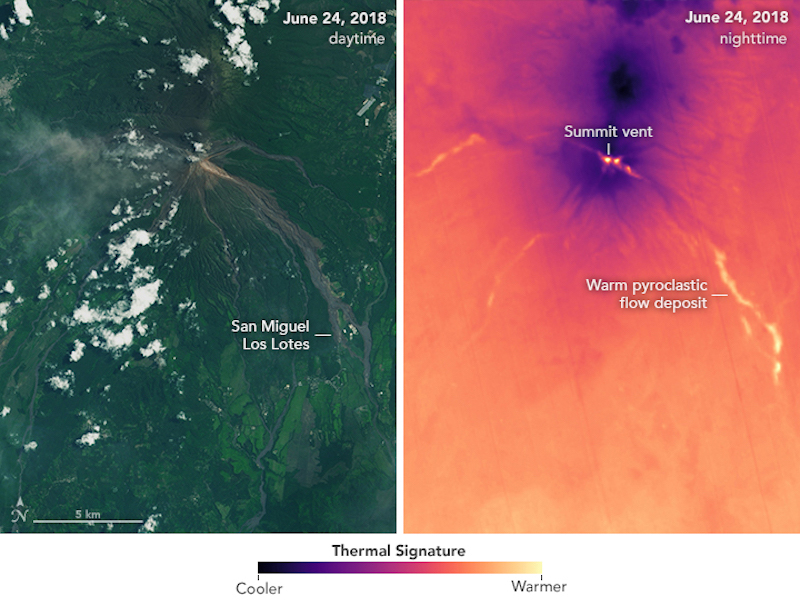

Explosions continued daily through the end of June 2018 at rates ranging from 4 to 9 explosions per hour, creating block avalanches that descended all the major ravines. Ash plumes rose to 4.2-4.9 km altitude (500-1,000 m above the summit) and drifted in multiple directions. On 18 and 22 June, fine-grained ashfall was reported in Panimache, Morelia, Sangre de Cristo, and Palo Verde. By 24 June, satellite imagery revealed that elevated heat was still discernable in several ravines that had been filled with pyroclastic flow debris earlier in the month (figure 103). Explosions on 27 and 28 June sent ash plumes W and ashfall was reported in Sangre de Cristo, Yepocapa, and communities a few km W of Fuego.

Geological Summary. Volcán Fuego, one of Central America's most active volcanoes, is also one of three large stratovolcanoes overlooking Guatemala's former capital, Antigua. The scarp of an older edifice, Meseta, lies between Fuego and Acatenango to the north. Construction of Meseta dates back to about 230,000 years and continued until the late Pleistocene or early Holocene. Collapse of Meseta may have produced the massive Escuintla debris-avalanche deposit, which extends about 50 km onto the Pacific coastal plain. Growth of the modern Fuego volcano followed, continuing the southward migration of volcanism that began at the mostly andesitic Acatenango. Eruptions at Fuego have become more mafic with time, and most historical activity has produced basaltic rocks. Frequent vigorous eruptions have been recorded since the onset of the Spanish era in 1524, and have produced major ashfalls, along with occasional pyroclastic flows and lava flows.

Information Contacts: Instituto Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanologia, Meteorologia e Hydrologia (INSIVUMEH), Unit of Volcanology, Geologic Department of Investigation and Services, 7a Av. 14-57, Zona 13, Guatemala City, Guatemala (URL: http://www.insivumeh.gob.gt/); Coordinadora Nacional para la Reducción de Desastres (CONRED), Av. Hincapié 21-72, Zona 13, Guatemala City, Guatemala (URL: http://conred.gob.gt/www/index.php); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); NASA Earth Observatory, EOS Project Science Office, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Goddard, Maryland, USA (URL: http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/); NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (NASA/GSFC), Global Sulfur Dioxide Monitoring Page, Atmospheric Chemistry and Dynamics Laboratory, 8800 Greenbelt Road, Goddard, Maryland, USA (URL: https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/); Washington Volcanic Ash Advisory Center (VAAC), Satellite Analysis Branch (SAB), NOAA/NESDIS OSPO, NOAA Science Center Room 401, 5200 Auth Rd, Camp Springs, MD 20746, USA (URL: www.ospo.noaa.gov/Products/atmosphere/vaac, archive at: http://www.ssd.noaa.gov/VAAC/archive.html); Associated Press (URL: https://apnews.com/); AFP/Getty, Agence France-Presse (URL: http://www.afp.com/); BBC News (URL: https://www.bbc.com/); The Telegraph (URL: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/); Reuters (http://www.reuters.com/); The Express (URL: https://www.express.co.uk); Matthew Watson, School of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol, Twitter: @Matthew__Watson), (URL: https://twitter.com/Matthew__Watson); GeoGis, Twitter: @jlescriba, (URL: https://twitter.com/jlescriba).