Report on Colima (Mexico) — April 1996

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 21, no. 4 (April 1996)

Managing Editor: Richard Wunderman.

Colima (Mexico) Minor rockfalls; measurements of SO2 flux and fumarole temperatures

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 1996. Report on Colima (Mexico) (Wunderman, R., ed.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 21:4. Smithsonian Institution. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.BGVN199604-341040

Colima

Mexico

19.514°N, 103.62°W; summit elev. 3850 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

The following report summarizes geochemical monitoring from mid-1995 through early 1996. All measurements were carried out by the Colima Volcano Observatory group and visiting colleagues. Measurements included SO2 fluxes, as well as fumarole temperatures, gas condensate chemistry, and S-flank hot spring temperature and pH readings.

COSPEC SO2 measurements. Five COSPEC surveys between 25 August 1995 and 3 January 1996 measured SO2 values of <200 metric tons/day (table 3). The aircraft used were provided by the Mexican Navy (on three surveys) and the Colima Civil Protection authorities (on two surveys).

Table 3. Summary of COSPEC SO2 measurements at Colima, 25 August 1995-1 January 1996. Courtesy of Colima Volcano Observatory.

| Date | SO2 avg. (tons/day) | Wind speed (m/s) | Altitude (m) | Number of transects |

| 25 Aug 1995 | 197 ± 73 | 11.3 ± 1.6 | 3,048 | 5 |

| 10 Oct 1995 | 52 ± 19 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | 2,286 | 7 |

| 23 Nov 1995 | 166 ± 87 | 9.0 ± 2.5 | -- | 7 |

| 29 Nov 1995 | 43 ± 16 | 18.3 ± 1.3 | 3,658 | 9 |

| 03 Jan 1996 | 50 ± 13 | 6.2 ± 2.5 | 3,190 | 7 |

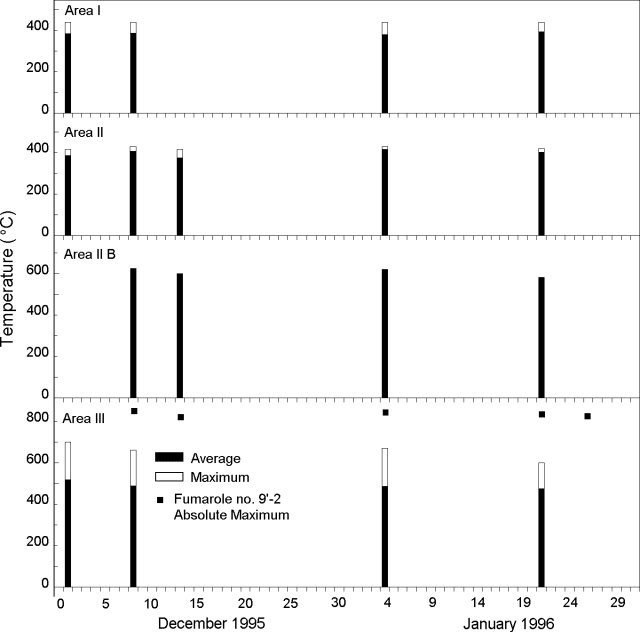

Summit fumaroles. On 1, 8, 13, and 27 December 1995, and 4, 21, and 26 January 1996, observatory scientists measured summit fumarole temperatures (figure 24) for the same three areas measured in July 1995 (BGVN 20:06 and 20:07). The new temperatures had maximum values at least 50°C lower (Area I), 25°C lower (Area II), and 80°C higher (area III) than those obtained in July 1995. The temperatures at each fumarole showed variable oscillations over the two months of observation (table 4).

|

Figure 24. Average and maximum fumarole temperatures at Colima, December 1995-January 1996. Courtesy of the Colima Volcano Observatory. |

Table 4. Summary of fumarole temperatures (°C) at Colima, December 1995-January 1996. Courtesy of Colima Volcano Observatory.

| Area | Fumarole | 01 Dec 1995 | 08 Dec 1995 | 13 Dec 1995 | 17 Dec 1995 | 04 Jan 1996 | 21 Jan 1996 | 26 Jan 1996 |

| I | 1 | 365 | 382 | -- | 354 | 366 | 411 | -- |

| I | 2 | 422 | 427 | -- | 405 | 409 | 409 | -- |

| I | 3 | 442 | 437 | -- | 409 | 439 | 440 | -- |

| I | 4 | 430 | 428 | -- | 417 | 412 | 408 | -- |

| I | 5 | 281 | 265 | -- | -- | 255 | 268 | -- |

| II | 6 | 388 | 434 | 387 | -- | 428 | 386 | -- |

| II | 7 | 420 | 427 | 421 | -- | 426 | 420 | -- |

| II | 8 | 385 | 397 | 330 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| II | 9 | 380 | 384 | 377 | -- | 401 | 397 | -- |

| II-B | 9' | -- | 628 | 610 | -- | 623 | 592 | -- |

| III | 9'-2 | -- | 856 | 825 | -- | 855 | 846 | 844 |

| III | 10 | 365 | 370 | -- | -- | 357 | 371 | -- |

| III | 11 | 370 | 386 | -- | -- | 413 | 402 | -- |

| III | 12 | 608 | 548 | -- | -- | 534 | 546 | -- |

| III | 13 | 700 | 670 | -- | -- | 684 | 636 | -- |

| III | 14 | 552 | 471 | -- | -- | 475 | 503 | -- |

During ascents on 1 and 8 December, extremely good visibility facilitated access to the dome area. This led to the discovery of high-temperature fumaroles never before measured by the Colima group. Fumaroles 12 and 13 in Area III were discovered on 1 December. It was not possible to establish the age of these fumaroles. Their high temperatures strongly influenced the average and maximum values for their area. However, this is not a proof of an overall increase in the temperature of the system. Fumarole 9' was found on 8 December at a "new" near-summit area called II-B, located roughly midway between areas II and III. The same day, J.C. Gavilanes discovered an incandescent fumarole (9'-2) in Area III. A reddish incandescence was visible ~30 cm below the surface inside its degassing hole. During the 13 December ascent, E. Tello took three gas samples from fumarole 8 in Area II. By 21 January this fumarole had disappeared.

On 26 January, another ascent allowed Yuri Taran to collect gas condensates from fumaroles 9 and 9'-2, with the following results: a) fumarole 9; temperature, 382°C; Cl, 6,730 ppm; F, 760 ppm; SO4, 5,400 ppm; B, 46 ppm; b) fumarole 9'-2; temperature, 738°C; Cl, 8,540 ppm; F, 620 ppm; SO4, 2,300 ppm; B, 12 ppm. These high-temperature condensates may indicate a proximal magma body.

Other observations. A rockfall from the summit area was noted by biologist D. Wroe while conducting research on the ecology of cats on Colima. He reported that on the night of 26 December he was awakened by dogs barking and this was immediately followed by a major rock avalanche.

Mr. Gonzáles-Dueñas, owner of the restaurant El Jacal de San Antonio (~10 km S of the volcano) witnessed about 10 rockfalls from the summit toward the S and SW during the first days of January 1996. This was confirmed by abundant whitish-yellowish dust covering the paths taken by the rockfalls. On 10 February, Saucedo and Komorowski witnessed one rockfall accompanied by a dust cloud that moved S; they also noted a whitish-yellowish dust along the rockfall's path.

Seven springs within 10 km of the summit on the S and SW flank had pH values of 5.9-6.9 and temperatures of 11-32°C. The highest temperature (30-32°C) and a high pH (6.2-6.8) was found at the San Antonio spring (7 km SSW of the summit). Only the San Antonio spring had been measured previously.

Geological Summary. The Colima complex is the most prominent volcanic center of the western Mexican Volcanic Belt. It consists of two southward-younging volcanoes, Nevado de Colima (the high point of the complex) on the north and the historically active Volcán de Colima at the south. A group of late-Pleistocene cinder cones is located on the floor of the Colima graben west and east of the complex. Volcán de Colima (also known as Volcán Fuego) is a youthful stratovolcano constructed within a 5-km-wide scarp, breached to the south, that has been the source of large debris avalanches. Major slope failures have occurred repeatedly from both the Nevado and Colima cones, producing thick debris-avalanche deposits on three sides of the complex. Frequent recorded eruptions date back to the 16th century. Occasional major explosive eruptions have destroyed the summit (most recently in 1913) and left a deep, steep-sided crater that was slowly refilled and then overtopped by lava dome growth.

Information Contacts: Juan Carlos Gavilanes Ruiz, Carlos Navarro Ochoa, Abel Cortés Cortés, Ricardo Sauced Girón, Juan José Ramírez Ruiz, Eliseo Alatorre Chávez, and Vyacheslav Zobin, Colima Volcano Observatory, Universidad de Colima, Ave. 25 de Julio 965, Colima 28045, Colima, México; Jean-Christophe Komorowski, Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, Observatoires Volcanologiques, 4 Place Jussieu, Boite 89, 75252 Paris, Cedex 05, France; Enrique Tello, Gerencia de Geotermia de la Comisión Federal de Electricidad, Morelia, Michoacán, México; Yuri Taran, Instituto de Geofísica, UNAM, Ciudad Universitaria, 04510 México D.F., México; Andrew M. Burton and Duggins Wroe, OCEAN, 22 de Diciembre no.1, Col. M.A. Chamacho, Naucalpan 53910, México; Michael Sheridan, Geology Department, State University of New York, Buffalo, NY 14260, USA; Marina Belousova, Alexander Belousov, and Volodya Churikov, Institute of Volcanic Geology and Geochemistry, Piip 9, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, 683006, Russia; Milton A. Garcés, Alaska Volcano Observatory, Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK 99775-7320, USA.