Report on Raoul Island (New Zealand) — March 2006

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 31, no. 3 (March 2006)

Managing Editor: Richard Wunderman.

Raoul Island (New Zealand) Eruption on 17 March 2006 preceded by 5 days of earthquakes; 1 fatality

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 2006. Report on Raoul Island (New Zealand) (Wunderman, R., ed.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 31:3. Smithsonian Institution. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.BGVN200603-242030

Raoul Island

New Zealand

29.27°S, 177.92°W; summit elev. 516 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

An eruption took place on 17 March 2006 at Raoul Island, killing one person. Brad Scott, New Zealand Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences (GNS), reported that on the evening of 12 March 2006 earthquakes began near Raoul Island. More than 200 earthquakes were recorded in the first 24 hours, with many of the larger events felt on the island. Earthquakes continued throughout the week, but the numbers gradually decreased.

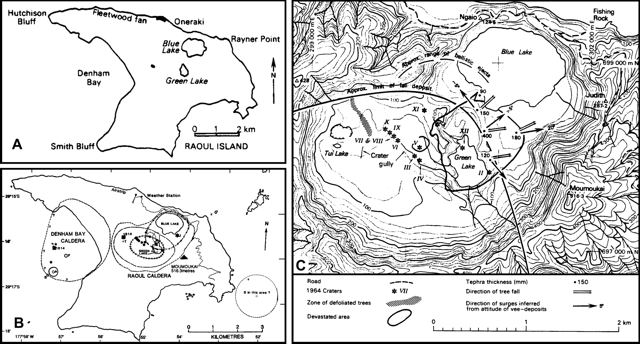

An eruption from the Green Lake crater, within the Raoul caldera (figure 2), began at 0821 on 17 March. Other than the precursory seismicity, no water-level or temperature changes were observed, even only 24 hours before the eruption. Based on data from the seismograph on the island, the eruption appears to have continued for up to 30 minutes, although the most intense part of the eruption lasted for only 5 to 10 minutes. Following the eruption, the rate of earthquake activity doubled, but by 23 March the number of earthquakes was reduced to 10-20 per day. No thermal anomalies were detected by the MODIS satellite system during March 2006.

The 2006 eruption blew over mature trees out to ~ 200 m and deposited dark gray mud and large ballistic blocks. Many of the steep crater margins had post-eruption collapses marked by fresh landslides.

The New Zealand Department of Conservation evacuated five staff members from the island, but one worker, taking water-temperature measurements at Green Lake at the time of the eruption, was killed. Devastation left by the eruption thwarted efforts to find the missing worker (figure 3). A news story reported that the missing man left around 0730 on 17 March to walk to Green Lake. An hour later the volcano erupted.

|

Figure 3. Photo reportedly taken by the rescue helicopter pilot John Funnell of the area affected by the volcanic eruption on Raoul Island, 17 March 2006. AP Photo; photo credit to John Funnell. |

Volcano monitoring of the Raoul crater lakes started after the 1964 eruption, as these lakes responded measurably before that event, consistent with a long-lived hydrothermal system. There are low-temperature (boiling-point) fumaroles in the vicinity of Green Lake and minor seepages of hydrothermal brine from the system (boiling hot springs) along Oneraki Beach, outside of the caldera. The gases have strong hydrothermal signatures (as opposed to proximal magmatic). As such, they do not suggest single-phase vapor transport directly from a magmatic source to the surface, but rather are indicative of the presence of boiling hydrothermal brine at depth. GNS has no quantitative data from Denham Bay (offshore to the W of the island, but scientists from the organization found boiling-point (100° C) steaming ground on the steep crater walls, and gas and water seeps in the sea. Historical observations of volcanic eruptions from this caldera (and Raoul caldera) point to the likely existence of a sizable active system residing there.

Still and video footage taken of the post-eruptive scene on 17 March 2006 showed many new craters and reactivation of 1964 craters. The main steam columns were derived from Crater I, Marker Bay, and Crater XI. Fumarolic activity appeared near the mouth of Crater Gully and the stream that drains from Crater V. The area NW of Bubbling Bay, where there had been a fumarole, contained a crater about 20-30 m across.

In the main body of Green Lake there were two areas of strong upwelling. One occurred near the end of the peninsula S of Crater XII (a promontory that had been explosively removed). Jagged rocks were visible in the lake where it had been 2-4 m deep. There was also a new feature about 200-300 m N of Green Lake's Crater XII (figure 2B); the new feature included a moat near the edge of the crater floor, which contained a vigorously active vent. Green Lake's surface did not appear elevated at the time of the post-eruption 17 March observations.

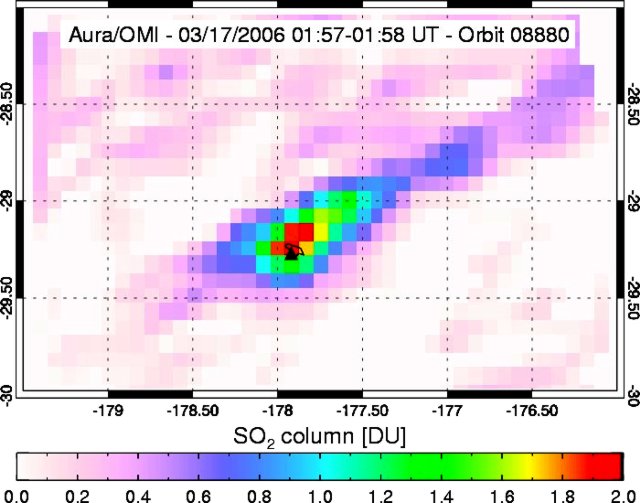

Sulfur dioxide (SO2) was detected by satellite about 5 hours after the 17 March eruption (figure 4). SO2 data was collected by the Aura Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI), which is affiliated with the University of Maryland, the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI), and the Finnish Meteorological Institute (FMI). The highest SO2 values stood over and adjacent to the island and reached as high as two Dobson Units (DU, figure 4). Simon Carn noted that the total mass of SO2 in figure 4 was ~ 200 tons. Subsequent observations did not detect further SO2 discharge.

An aerial inspection on 21 March made from a Royal New Zealand Air Force Orion aircraft allowed excellent views of both the Raoul and Denham Bay calderas. Visible steam discharge from the vents had declined significantly owing to a 6-8 m rise in Green Lake's water level and the consequent drowning of most of the active vents. The lake level did not appear to have reached overflow level. Landsliding and collapse also blocked Crater I. Vigorous upwelling and gas discharge was still obvious through Green Lake, which appeared very warm.

There was no evidence of further eruptions since 17 March, nor was there any evidence that activity had occurred from the 1964 craters adjacent to Crater Gully (i.e. craters III, IV, and VI-X). However, many new craters formed at the mouth of Crater Gully where hot bare ground had been present. There was a possible NE-trend through the vents from Crater Gully to NE of Crater XII. In 1964 the craters aligned along three parallel fractures that tended NW. Heightened activity was not confined to the lake.

In Denham Bay GNS scientists observed a weak plume of discolored water approximately coincident with the vent area. There was evidence of hydrothermal seepage along most of the beach (milky discoloration indicating mixing of hydrothermal brine and seawater). There were also discharges in the rocky bay halfway between Hutchison Bluff and the NW end of Denham beach (figure 2A). If these are confirmed as hydrothermal seepages, they represent a significant rise in the surface of the hydrothermal fluids in the system, consistent with that observed in the caldera.

On 23 March 2006, the GNS reported that scientists who flew over noted that the hydrothermal system under the island showed signs of over-pressuring. GNS volcanologist Bruce Christenson stated, "From our aerial observations, it is clear that the heat, gas, and water that are discharging into Green Lake are making this part of the volcano's hydrothermal system unstable." Several new steam vents opened in and around Green Lake during the eruption and some old ones had reactivated. Many of these were drowned as a result of lake-level rise. According to Christenson, "one explanation for the increased hydrothermal activity is that it is being driven by the intrusion of magma at depth."

Steve Sherburn of GNS reported on 24 March on the GeoNet website (the New Zealand GeoNet Project provides real-time monitoring and data collection for rapid response and research into earthquake, volcano, landslide, and tsunami hazards) that over the last few days the level of earthquake activity at or close to Raoul Island had continued to decline to a current level of only 5-10 earthquakes per day, most of which were probably too small to be felt on the island. There is no unequivocal seismic evidence for magma movement (such as the strong volcanic tremor observed before the 1964 eruption). Careful seismic monitoring of Raoul Island will continue.

Brad Scott reported on 3 April 2006 that activity continued to decline in the Green Lake crater area. The most recently available photographs showed the water level continuing to rise slowly in Green Lake, but it had not reached overflow level. Over the last few days the level of earthquake activity at or close to Raoul Island continued to decline and in early April there were only 2-5 earthquakes per day being recorded.

References. Latter, J.H.; Lloyd, E.F.; Smith, I.E.M.; and Nathan, S., 1992, Volcanic hazards in the Kermadec Islands, and at submarine volcanoes between Southern Tonga and New Zealand: Volcanic Hazards Information Series, no. 4 (CD 303), New Zealand Ministry of Civil Defence, 45 p. (Booklet) ISBN 0-477-07472-3Lloyd, E.F., and Nathan, S., 1981, Geology and tephrochronology of Raoul Island, Kermadec Group, New Zealand: New Zealand Geological Survey Bulletin, no. 95, 105 p. (includes map in back pocket).

Geological Summary. Anvil-shaped Raoul Island is the largest and northernmost of the Kermadec Islands. During the past several thousand years volcanism has been dominated by dacitic explosive eruptions. Two Holocene calderas exist, the older of which cuts the center the island and is about 2.5 x 3.5 km wide. Denham caldera, formed during a major dacitic explosive eruption about 2200 years ago, truncated the W side of the island and is 6.5 x 4 km wide. Its long axis is parallel to the tectonic fabric of the Havre Trough that lies W of the volcanic arc. Historical eruptions during the 19th and 20th centuries have sometimes occurred simultaneously from both calderas, and have consisted of small-to-moderate phreatic eruptions, some of which formed ephemeral islands in Denham caldera. An unnamed submarine cone, one of several located along a fissure on the lower NNE flank, has also erupted during historical time, and satellitic vents are concentrated along two parallel NNE-trending lineaments.

Information Contacts: Brad Scott, Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences (GNS), Wairakei Research Centre, 114 Karetoto Road, Taupo, New Zealand (URL: http://www.geonet.org.nz/, http://www.gns.cri.nz/).