Report on Fuego (Guatemala) — August 2021

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 46, no. 8 (August 2021)

Managing Editor: Edward Venzke.

Edited by Kadie L. Bennis.

Fuego (Guatemala) Daily explosions, ash plumes, ashfall, and incandescent block avalanches during April-July 2021

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 2021. Report on Fuego (Guatemala) (Bennis, K.L., and Venzke, E., eds.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 46:8. Smithsonian Institution. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.BGVN202108-342090

Fuego

Guatemala

14.4748°N, 90.8806°W; summit elev. 3799 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Volcán de Fuego, located in Guatemala, has been vigorously erupting since 2002, with historical eruptions dating back to 1531. Major eruptions have been characterized by ashfalls, pyroclastic flows, lava flows, and lahars. More recently, activity has consisted of ash plumes, ashfall, incandescent block avalanches, and lava flows (BGVN 46:04). Similar activity continued during this reporting period of April through July 2021, dominated by daily explosions, ash plumes, ashfall, and incandescent block avalanches. Information primarily comes from daily reported by the Instituto Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanología, Meteorología e Hidrologia (INSIVUMEH), Washington Volcanic Ash Advisory Center (VAAC), and various satellite data.

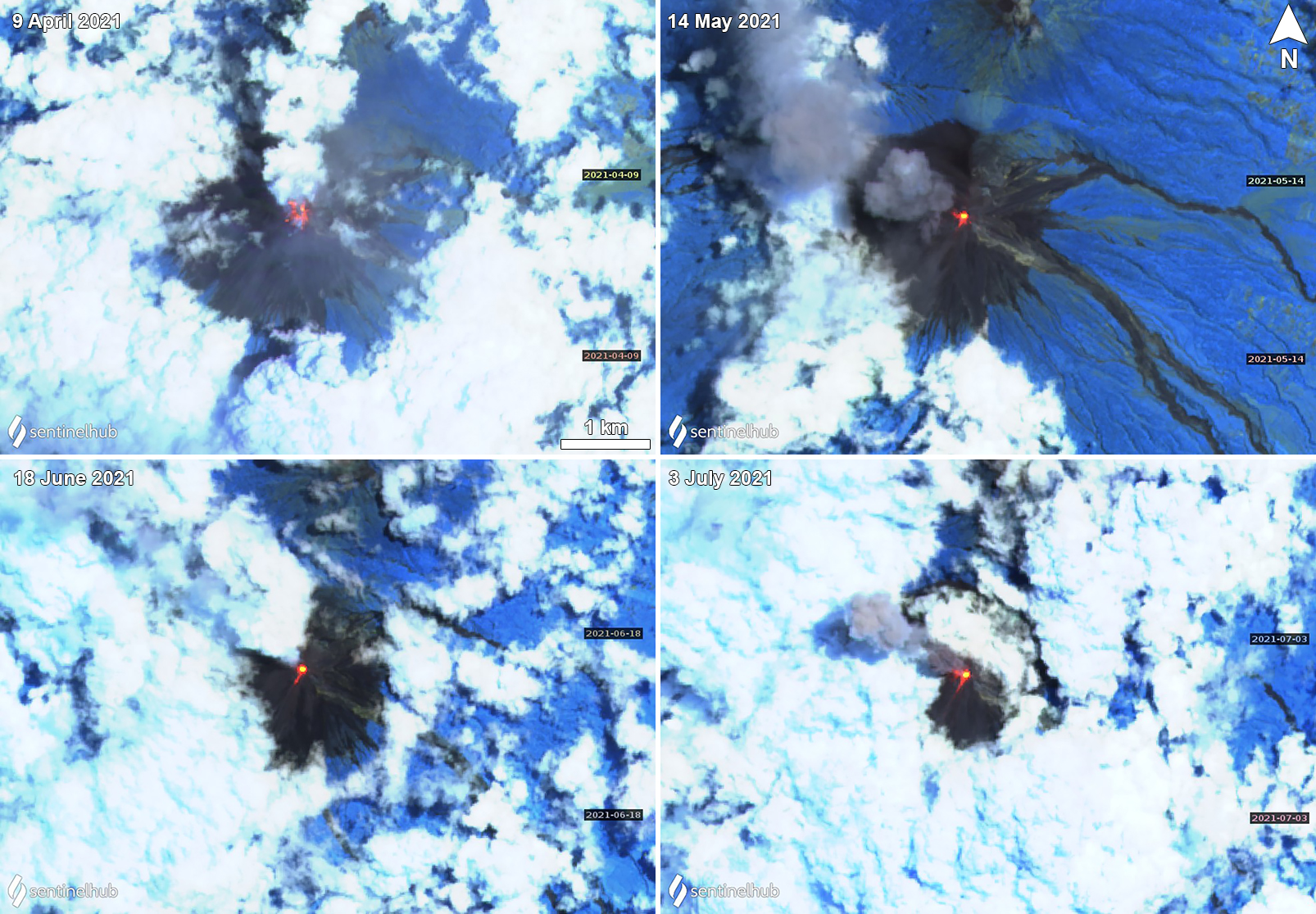

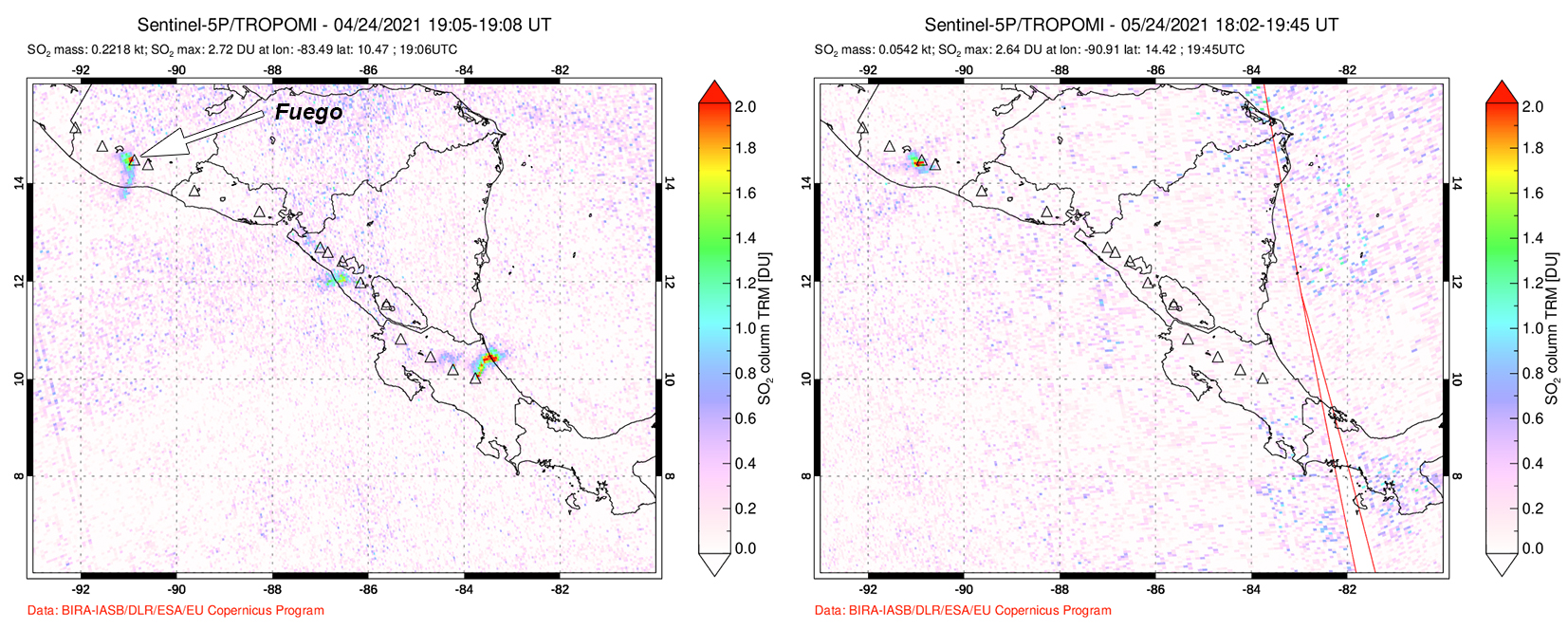

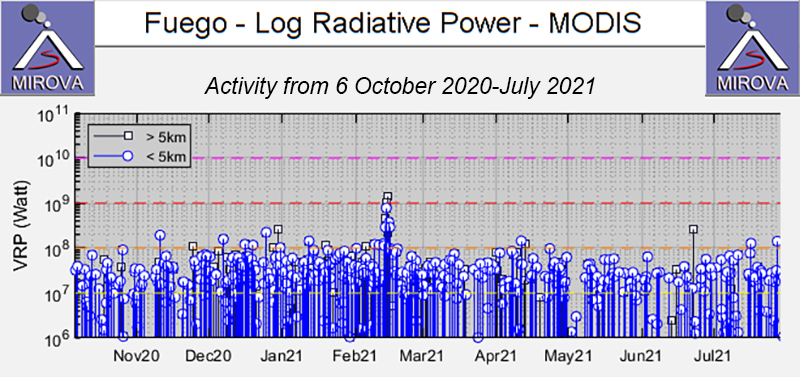

Summary of activity during April-July 2021. Hourly explosions were reported at Fuego during April-July 2021 that vibrated roofs and windows in nearby communities. These explosions generated gray ash plumes that rose 4.3-4.9 and generally drifted W and SW, the highest of which occurred on 25 April. The Washington VAAC issued 422 daily ash advisories during the reporting period. Ashfall was common throughout this period in several nearby communities, dominantly Panimaché I and II (8 km SW), Morelia (9 km SW), Santa Sofía (12 km SW), El Porvenir (8 km ENE), Sangre de Cristo (8 km WSW), Yepocapa (8 km NW). Occasional white gas-and-steam plumes accompanied the explosive activity, rising as high as 4.5 km altitude. Incandescent block avalanches accompanied the explosions, descending several flanks, such as the Seca (W), Ceniza (SSW), Trinidad (S), and Taniluyá (SW) drainages and reaching as far as vegetated areas. Incandescent ejecta was observed as high as 450 m above the crater during most nights and early mornings. According to the MIROVA graph (Log Radiative Power), thermal activity was consistently strong and frequent during April through July (figure 148). The MODVOLC algorithm detected 39 thermal alerts during six days in April, nine days in May, five days in June, and six days in July. Sentinel-2 infrared satellite imagery showed strong thermal anomalies in the summit crater, which represents the incandescent block avalanches that descended the S and SW flanks as a result of persistent explosions (figure 149). Many of these avalanches were accompanied by gray ash plumes. Weak sulfur dioxide emissions were infrequently observed in Sentinel-5P TROPOMI satellite imagery on 24 April and 24 May, which drifted S and W, respectively (figure 150).

Table 23. Eruptive activity was consistently high at Fuego throughout April-July 2021 with multiple explosions every hour, ash plumes, block avalanches, and near-daily ashfall in nearby communities. Courtesy of INSIVUMEH daily reports.

| Month | Explosions per hour | Ash plume heights (km) | Ash plume distance (km) and direction | Drainages affected by block avalanches | Communities reporting ashfall |

| Apr 2021 | 2-14 | 4.3-4.9 | 8-20; S, SE, SW, W, NE, NW, and E | Seca, Taniluyá, Ceniza, Trinidad, Santa Teresa, Las Lajas, and Honda | Panimaché I and II, Morelia, Santa Sofía, El Porvenir, Sangre de Cristo, Yepocapa, La Rochela, Palo Verde, Yucales, and Asunción |

| May 2021 | 3-17 | 4.2-4.8 | 5-15; S, SW, N, NE, W, and NW | Seca, Ceniza, Taniluyá, Trinidad, Las Lajas, Honda, and Santa Teresa | Panimaché I and II, Morelia, El Porvenir, Santa Sofía, Sangre de Cristo, Yepocapa, Yucales, San Pedro, La Soledad, San José calderas, Acatenango, and Palo Verde |

| Jun 2021 | 3-15 | 4.3-4.8 | 10-20; W, NW, SW, S, SE, N, NE, and E | Ceniza, Taniluyá, Trinidad, Santa Teresa, Seca, Las Lajas, and Honda | Panimaché I and II, Morelia, Santa Sofía, Yucales, Sangre de Cristo, Yepocapa, El Porvenir, Palo Verde, Ceilán, La Rochela, La Soledad, El Campamento, and El Zapote |

| Jul 2021 | 3-15 | 4.3-4.8 | 8-30; W, SW, NE, N, S, and NW | Ceniza, Taniluyá, Trinidad, Santa Teresa, Las Lajas, Honda, and Seca | Sangre de Cristo, Panimaché I and II, El Porvenir, Morelia, Santa Sofía, Yucales, Yepocapa, Palo Alto, Palo Verde, La Rochela, Ceilán, and La Conchita |

|

Figure 148. Consistently strong thermal anomalies continued at Fuego during April through July 2021. Courtesy of MIROVA. |

Frequent daily explosions continued during April. Two to fourteen explosion per hour were detected, which generated ash plumes that rose to 4.3-4.9 km altitude and drifted usually up to 15 km, and occasionally as far as 20 km in different directions. Ashfall was commonly reported in multiple communities, including Panimaché I and II, Morelia, Santa Sofía, El Porvenir, Sangre de Cristo, Yepocapa. Due to heavy rains on 16 April, lahars were observed in the Ceniza, Seca, and Mineral drainages. Additional ash was reported in La Rochela on the 20th, Palo Verde on the 23rd and 25th, Yucales (12 km SW) on the 26th, and Asuncion on the 29th. The explosions ejected material as high as 400 m above the crater and caused constant incandescent block avalanches to descend several flank drainages, including Seca, Taniluyá, Ceniza, Trinidad, Santa Teresa, Las Lajas (SE), and Honda.

Explosive activity during May was similar to previous months, with 3-17 explosions per hour that rattled windows and roofs in nearby communities. Gas-and-ash plumes rose to 4.2-4.8 km altitude and drifted as far as 15 km S, SW, N, NE, W, and NW. Near-daily reports of resulting ashfall affected mainly Panimaché I and II, Morelia, El Porvenir, Santa Sofía, Sangre de Cristo, Yepocapa, and Yucales. Ashfall was also observed in Palo Verde (5 May), La Soledad (11 km N) (20 May), San José calderas (20 May), Acatenango (20 May), and San Pedro (21 May). Block avalanches caused by frequent explosions descended the Seca, Ceniza, Taniluyá, Trinidad, Las Lajas, Honda, and Santa Teresa drainages, sometimes reaching vegetated areas, and incandescent material was ejected 100-450 m above the crater.

Loud explosions continued throughout June, with 3-15 explosions per hour that produced ash plumes that rose to 4.3-4.8 km altitude and drifted 10-20 km in different directions. Ash was observed primarily in Panimaché I and II, Morelia, Santa Sofía, Yucales, Sangre de Cristo, Yepocapa, and El Porvenir. Other communities receiving ashfall included Palo Verde, Ceilán, La Rochela, La Soledad, El Campamento, and El Zapote. Incandescent ejecta rose 100-400 m above the crater. Constant block avalanches were reported in the Ceniza, Taniluyá, Trinidad, Santa Teresa, Seca, Las Lajas, and Honda drainages, sometimes reaching vegetated areas. On 15 and 24 June, INSIVUMEH reported that lahars descended the Las Lajas and El Jute drainages on the SE flank, due to heavy rainfall; tree branches and blocks are large as 1.5 km in diameter were carried down the flanks.

During July, daily explosions persisted at a rate of 3-15 per hour, which produced gas-and-ash plumes that rose to 4.3-4.8 km altitude (figure 151). These plumes drifted 8-30 km primarily W and SW, resulting in ashfall in several nearby communities, including Sangre de Cristo, Panimaché I and II, El Porvenir, Morelia, Santa Sofía, Yucales, and Yepocapa. Other communities less affected included Palo Alto (13 July), Palo Verde (19 and 24 July), La Rochela (25 July), Ceilán (25 July), and La Conchita (29 July). During the night and early morning, crater incandescence was visible, accompanied by ejecta that rose 100-400 m above the crater. Explosions also generated constant block avalanches that descended drainages along the flanks, including Ceniza, Taniluyá, Trinidad, Santa Teresa, Las Lajas, Honda, and Seca, frequently reaching vegetation.

Geological Summary. Volcán Fuego, one of Central America's most active volcanoes, is also one of three large stratovolcanoes overlooking Guatemala's former capital, Antigua. The scarp of an older edifice, Meseta, lies between Fuego and Acatenango to the north. Construction of Meseta dates back to about 230,000 years and continued until the late Pleistocene or early Holocene. Collapse of Meseta may have produced the massive Escuintla debris-avalanche deposit, which extends about 50 km onto the Pacific coastal plain. Growth of the modern Fuego volcano followed, continuing the southward migration of volcanism that began at the mostly andesitic Acatenango. Eruptions at Fuego have become more mafic with time, and most historical activity has produced basaltic rocks. Frequent vigorous eruptions have been recorded since the onset of the Spanish era in 1524, and have produced major ashfalls, along with occasional pyroclastic flows and lava flows.

Information Contacts: Instituto Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanologia, Meteorologia e Hydrologia (INSIVUMEH), Unit of Volcanology, Geologic Department of Investigation and Services, 7a Av. 14-57, Zona 13, Guatemala City, Guatemala (URL: http://www.insivumeh.gob.gt/ ); Washington Volcanic Ash Advisory Center (VAAC), Satellite Analysis Branch (SAB), NOAA/NESDIS OSPO, NOAA Science Center Room 401, 5200 Auth Rd, Camp Springs, MD 20746, USA (URL: www.ospo.noaa.gov/Products/atmosphere/vaac, archive at: http://www.ssd.noaa.gov/VAAC/archive.html); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); NASA Global Sulfur Dioxide Monitoring Page, Atmospheric Chemistry and Dynamics Laboratory, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (NASA/GSFC), 8800 Greenbelt Road, Goddard, Maryland, USA (URL: https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/); Sentinel Hub Playground (URL: https://www.sentinel-hub.com/explore/sentinel-playground).