Recently Published Bulletin Reports

Ambrym (Vanuatu) New effusive eruption during January 2024

Popocatepetl (Mexico) Daily gas-and-ash emissions, ashfall, and occasional explosions during August-November 2023

Reventador (Ecuador) Daily explosions, gas-and-ash emissions, and incandescent avalanches during August-November 2023

Erta Ale (Ethiopia) Strong lava lake activity and lava overflows during June-November 2023

Ubinas (Peru) New eruption with explosions and ash plumes during June-December 2023

Kanaga (United States) Small explosion on 18 December 2023

Klyuchevskoy (Russia) New eruption consisting of Strombolian activity, lava flows and fountains, and ash plumes during June-December 2023

Agung (Indonesia) Three eruptive events reported in April, May, and December 2022

Saunders (United Kingdom) Persistent thermal anomalies from the summit crater lava lake during February 2023-January 2024

Tengger Caldera (Indonesia) Minor ash emission in December 2023; persistent weak thermal anomaly in the Bromo crater

Shishaldin (United States) New eruption with significant Strombolian explosions, ash plumes, and ashfall

Ioto (Japan) New eruption with discolored water, ejecta, and floating pumice during October-December 2023

Ambrym (Vanuatu) — February 2024  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Ambrym

Vanuatu

16.25°S, 168.12°E; summit elev. 1334 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

New effusive eruption during January 2024

Ambrym contains a 12-km-wide caldera and is part of the New Hebrides Arc, located in the Vanuatu archipelago. The two currently active craters within the caldera are Benbow and Marum, both of which have produced lava lakes, explosions, lava flows, and gas-and-ash emissions. The previous eruption occurred during late January 2022 and was characterized by ash plumes, sulfur dioxide plumes, and crater incandescence (BGVN 47:05). This report covers a new, short eruption during January 2024, which consisted of a lava effusion and an explosion. Information comes from the Vanuatu Meteorology and Geohazards Department (VMGD) and satellite data.

VMGD reported that at 2217 on 13 January an eruption began at Benbow Crater, based on webcam and seismic data. The eruption was characterized by a loud explosion, intense crater incandescence (figure 55), and gas-and-steam emissions. As a result, the Volcano Alert Level (VAL) was raised from 1 to 3 (on a scale of 0-5). A lava flow was reported in Benbow Crater, which lasted for four days. Satellite data showed that 1,116 tons of sulfur dioxide per day (t/d) were emitted on 14 January (figure 56). During the morning of 15 January, ground reports noted loud explosions and minor earthquakes. The sulfur dioxide flux on 15 January was 764 t/d. During 15-17 January activity decreased according to webcam images, seismic data, and field observations. No sulfur dioxide emissions were reported after 15 January. Gas-and-ash emissions also decreased, although they continued to be observed through 31 January, and crater incandescence was less intense (figure 57). The VAL was lowered to 2 on 17 January.

Geologic Background. Ambrym is a large basaltic volcano with a 12-km-wide caldera formed during a major Plinian eruption with dacitic pyroclastic flows about 1,900 years ago. A thick, almost exclusively pyroclastic sequence, initially dacitic then basaltic, overlies lava flows of a pre-caldera shield volcano. Post-caldera eruptions, primarily from Marum and Benbow cones, have partially filled the caldera floor and produced lava flows that ponded on the floor or overflowed through gaps in the caldera rim. Post-caldera eruptions have also formed a series of scoria cones and maars along a fissure system oriented ENE-WSW. Eruptions have been frequently reported since 1774, though mostly limited to extra-caldera eruptions that would have affected local populations. Since 1950 observations of eruptive activity from cones within the caldera or from flank vents have occurred almost yearly.

Information Contacts: Geo-Hazards Division, Vanuatu Meteorology and Geo-Hazards Department (VMGD), Ministry of Climate Change Adaptation, Meteorology, Geo-Hazards, Energy, Environment and Disaster Management, Private Mail Bag 9054, Lini Highway, Port Vila, Vanuatu (URL: http://www.vmgd.gov.vu/, https://www.facebook.com/VanuatuGeohazardsObservatory/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Popocatepetl (Mexico) — January 2024  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Popocatepetl

Mexico

19.023°N, 98.622°W; summit elev. 5393 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Daily gas-and-ash emissions, ashfall, and occasional explosions during August-November 2023

Popocatépetl, located 70 km SE of Mexica City, Mexico, contains a 400 x 600 m-wide summit crater. Records of activity date back to the 14th century; three Plinian eruptions, the most recent of which took place about 800 CE, have occurred since the mid-Holocene, accompanied by pyroclastic flows and voluminous lahars that swept basins below the volcano. The current eruption period began in January 2005, characterized by numerous episodes of lava dome growth and destruction within the summit crater. Recent activity has been characterized by daily gas-and-ash emissions, ashfall, and explosions (BGVN 48:09). This report covers similar activity during August through November 2023, according to daily reports from Mexico's Centro Nacional de Prevención de Desastres (CENAPRED) and various satellite data.

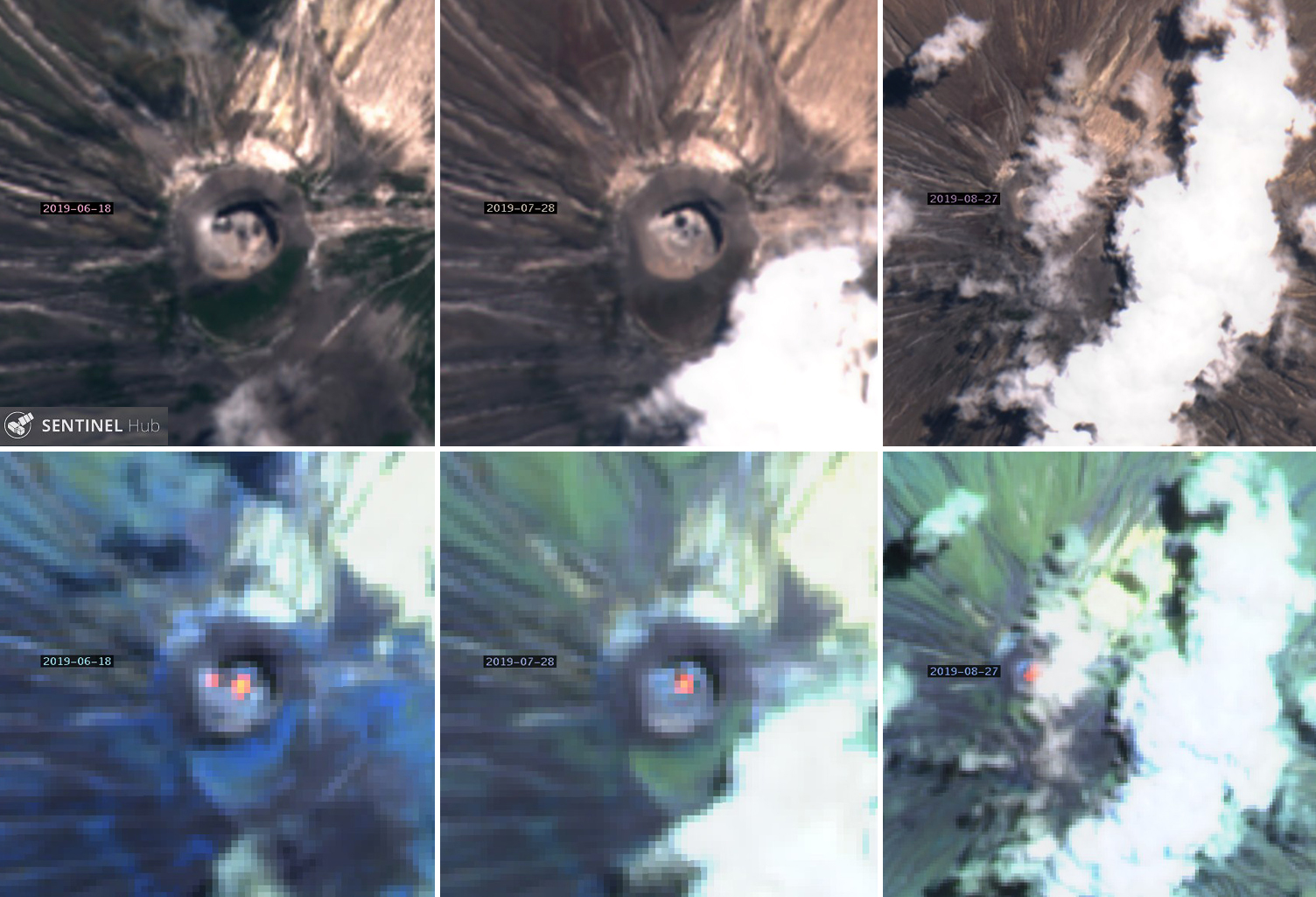

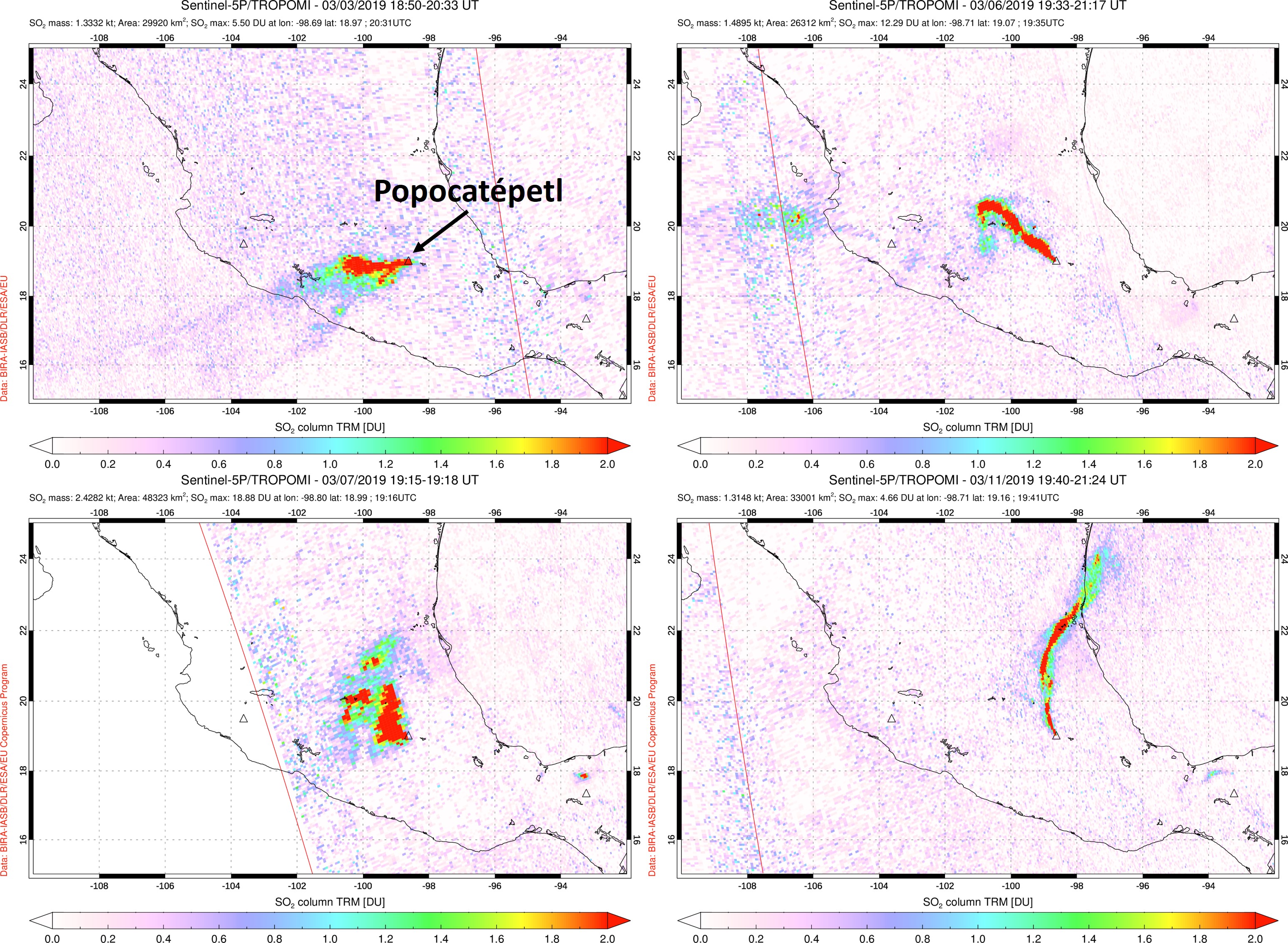

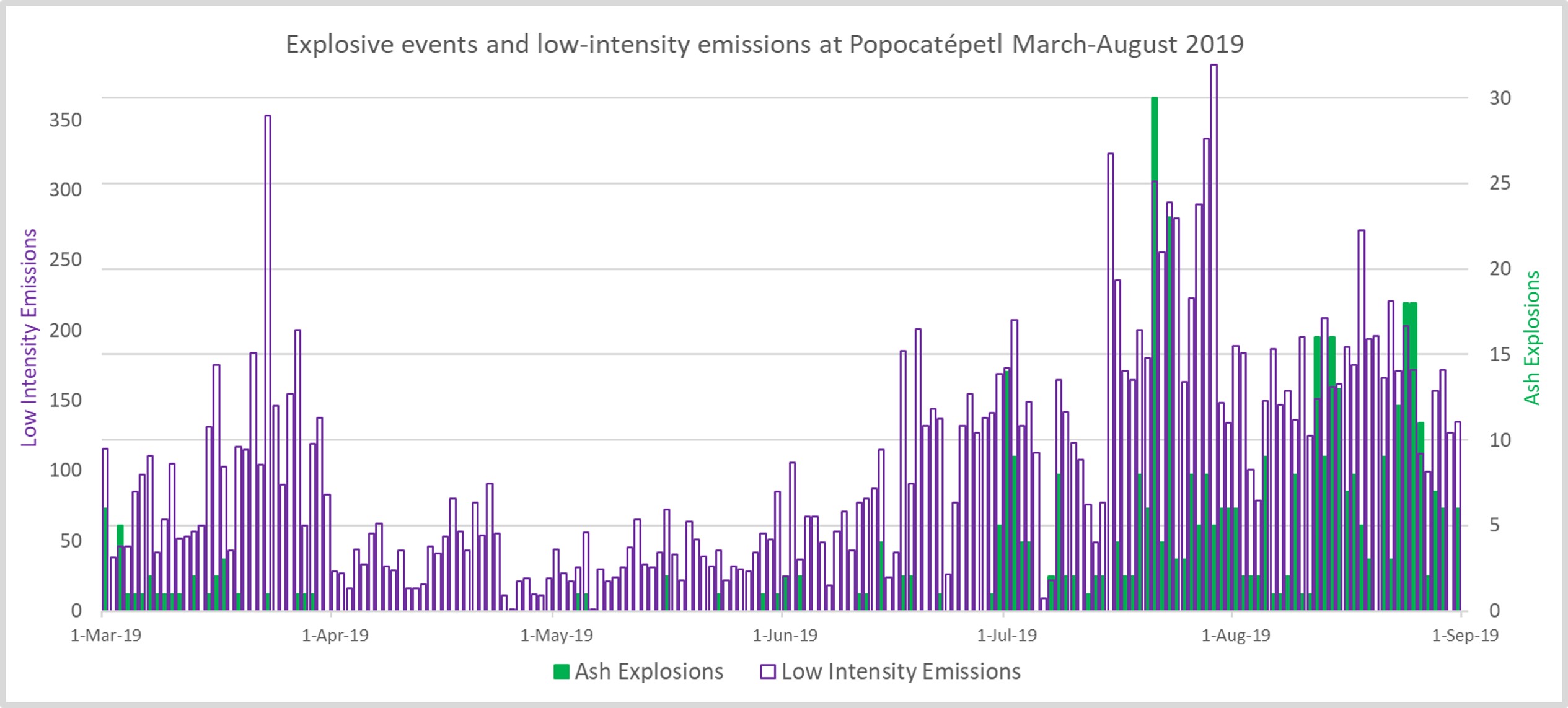

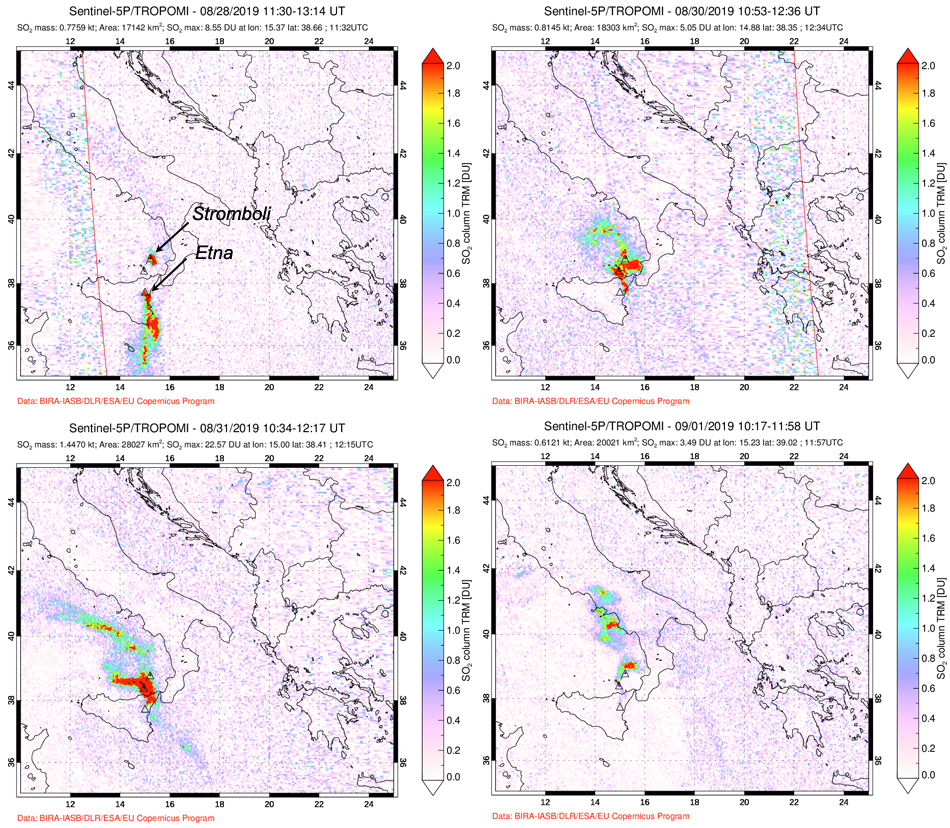

Daily gas-and-steam emissions, containing some amount of ash, continued during August through November 2023. CENAPRED reported the number of low-intensity gas-and-ash emissions or “exhalations” and the minutes of tremor, which sometimes included harmonic tremor in their daily reports (figure 220). A total of 21 volcano-tectonic (VT) tremors were detected throughout the reporting period. The average number of exhalations was 117 per day, with a maximum number of 640 on 25 September. Frequent sulfur dioxide plumes that exceeded two Dobson Units (DU) and drifted in multiple directions were visible in satellite data from the TROPOMI instrument on the Sentinel-5P satellite (figure 221).

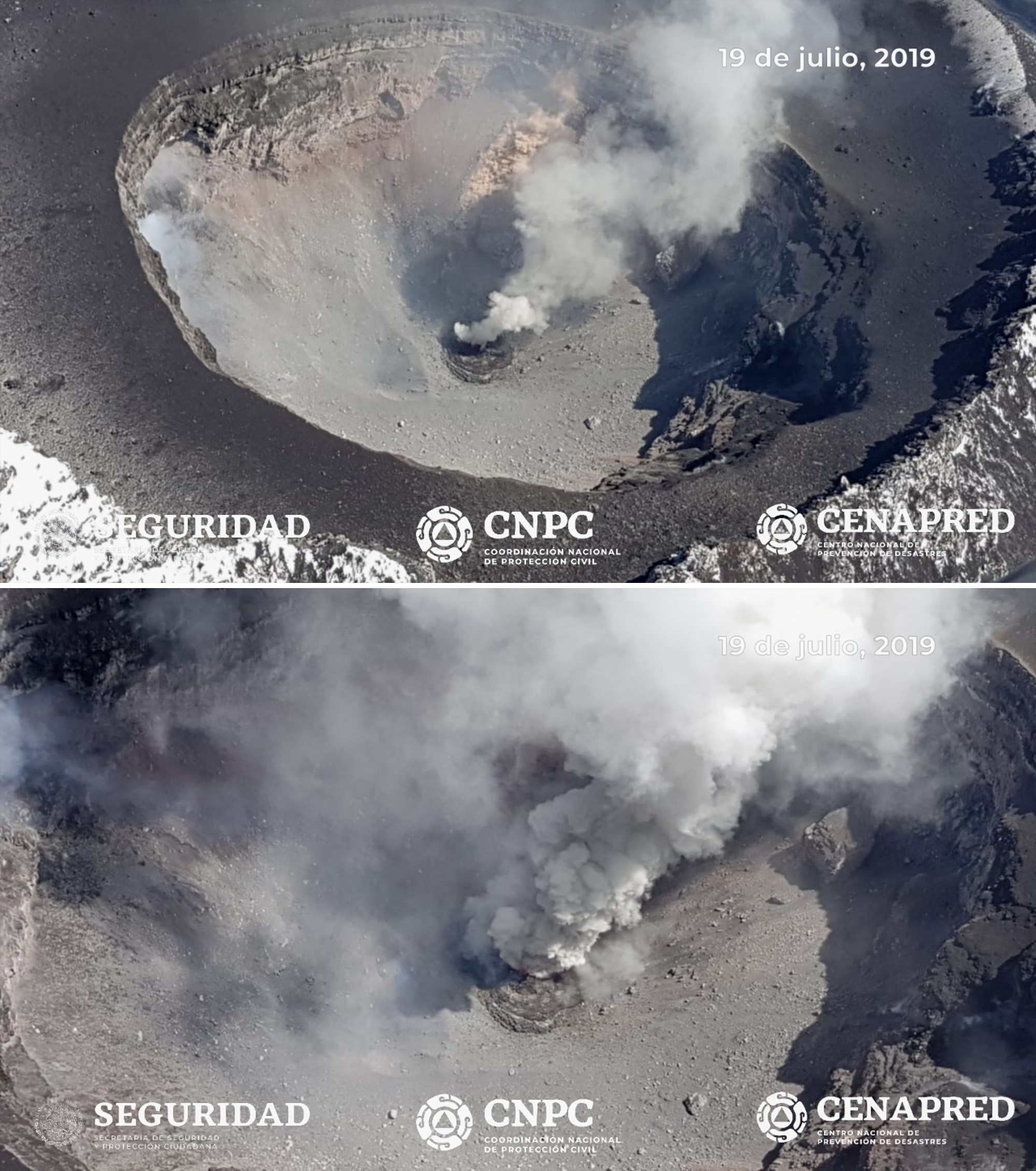

Activity during August was relatively low and mainly consisted of occasional explosions, ash emissions, and light ashfall. There were 30 explosions (25 minor explosions and four moderate explosions), and nine VT-type events detected. An average number of 60 exhalations occurred each day, which mostly consisted of water vapor, volcanic gases, and a small amount of ash. On 2 August the National Center for Communications and Civil Protection Operations (CENACOM) reported light ashfall in Ocuituco (22 km SW), Yecapixtla (31 km SW), Cuautla (43 km SW), and Villa de Ayala (47 km SW). On 7 August light ashfall was observed in Atlautla (16 km W). A minor explosion at 0305 on 11 August was accompanied by crater incandescence. Explosions at 0618 on 13 August produced a gas-and-ash plume that rose above the summit, and at 0736 another explosion produced a puff of gas-and-ash (figure 222). Two minor explosions were detected at 0223 and 0230 on 16 August that generated eruptive columns with low ash content rising 800 m and 700 m above the crater, respectively. On 24 August an eruptive event lasted 185 minutes and consisted of light ash emissions that did not exceed 300 m above the crater. According to the Washington VAAC, ash plumes identified in daily satellite images rose to 4.6-7.6 km altitude and drifted in multiple directions, the highest of which occurred on 29 August.

There was an average of 156 exhalations each day during September, a monthly total of seven VT-type events, and 29 explosions, 14 of which were minor and nine of which were moderate. A gas-and-ash plume rose to 2 km above the summit and drifted WSW at 1216 on 1 September. CENACOM reported at 1510 observations of ashfall in Ozumba (18 km W), Atlautla, Tepetlixpa (20 km W), and Ecatzingo (15 km SW), as well as in Morelos in Cuernavaca (65 km WSW), Temixco (67 km WSW), Huitzilac (67 km W), Tepoztlán (49 km W), and Jiutepec (59 km SW). The next day, gas-and-ash plumes rose to 2 km above the summit (figure 223). At 1100 ashfall was reported in Amecameca (15 km NW), Ayapango (24 km WNW), Ozumba, Juchitepec, Tenango del Aire (29 km WNW), Atlautla, and Tlalmanalco (27 km NW). A gas-and-ash plume rose to 1 km above the summit and drifted WNW at 1810. During 5-6, 8-9, 12, 14, 19, and 24-25 September ashfall was reported in Amecameca, Atlautla, Ozumba, Tenango del Aire, Tepetlixpa, Juchitepec, Cuernavaca, Ayala, Valle de Chalco (44 km NW), Ixtapaluca (42 km NW), La Paz (50 km NW), Chimalhuacán, Ecatepec, Nezahualcóyotl (60 km NW), Xochimilco (53 km SE), Huayapan, Tetela del Volcano (20 km SW), Yautepec (50 km WSW), Cuautla (43 km SW), Yecapixtla (30 km SW) and possibly Tlaltizapán (65 km SW), Tlaquiltenango, and Tepalcingo. According to the Washington VAAC, ash plumes identified in daily satellite images rose to 5.8-9.1 km altitude and drifted in multiple directions, the highest of which was identified during 1-2 August.

Activity during October and November was relatively low. An average of 179 exhalations consisting of gas-and-steam and ash emissions were reported during October and 73 during November. Only one VT-type event and two explosions were detected during October and four VT-type events and one explosion during November. A satellite image from 0101 on 14 October showed ash fanning out to the NW at 6.7 km altitude and an image from 0717 showed a continuously emitted ash plume drifting WNW and NW at the same altitude. Ash emissions at 1831 on 14 October were ongoing and visible in webcam images slowly drifting W at an altitude of 6.4 km altitude (figure 224). On 24 October a tremor sequence began at 0310 that generated a gas-and-ash plume that rose 800 m above the summit and drifted W. Another tremor sequence occurred during 1305-1900 on 25 October that consisted of continuous ash emissions. Ash plumes identified in daily satellite images rose to 5.5-8.5 km altitude and drifted in different directions during October, according to the Washington VAAC. The highest ash plume was detected on 23 October. During 10-13 November ash plumes rose to 6.7 km altitude and drifted N, NNW, NE, and NW. On 13 November a M 1.5 VT-type event was detected at 0339 and light ashfall was reported in Amecameca, Cocotitlán (34 km NW), and Tenango del Aire, and Ocuituco. On 14 November ash plumes rose to 6 km altitude and drifted N, NE, and SE and light ashfall was reported in Cuernavaca (64 km W). The Washington VAAC reported frequent ash plumes that rose to 5.8-7.9 km altitude and drifted in several directions; the highest ash plume was recorded on 28 November.

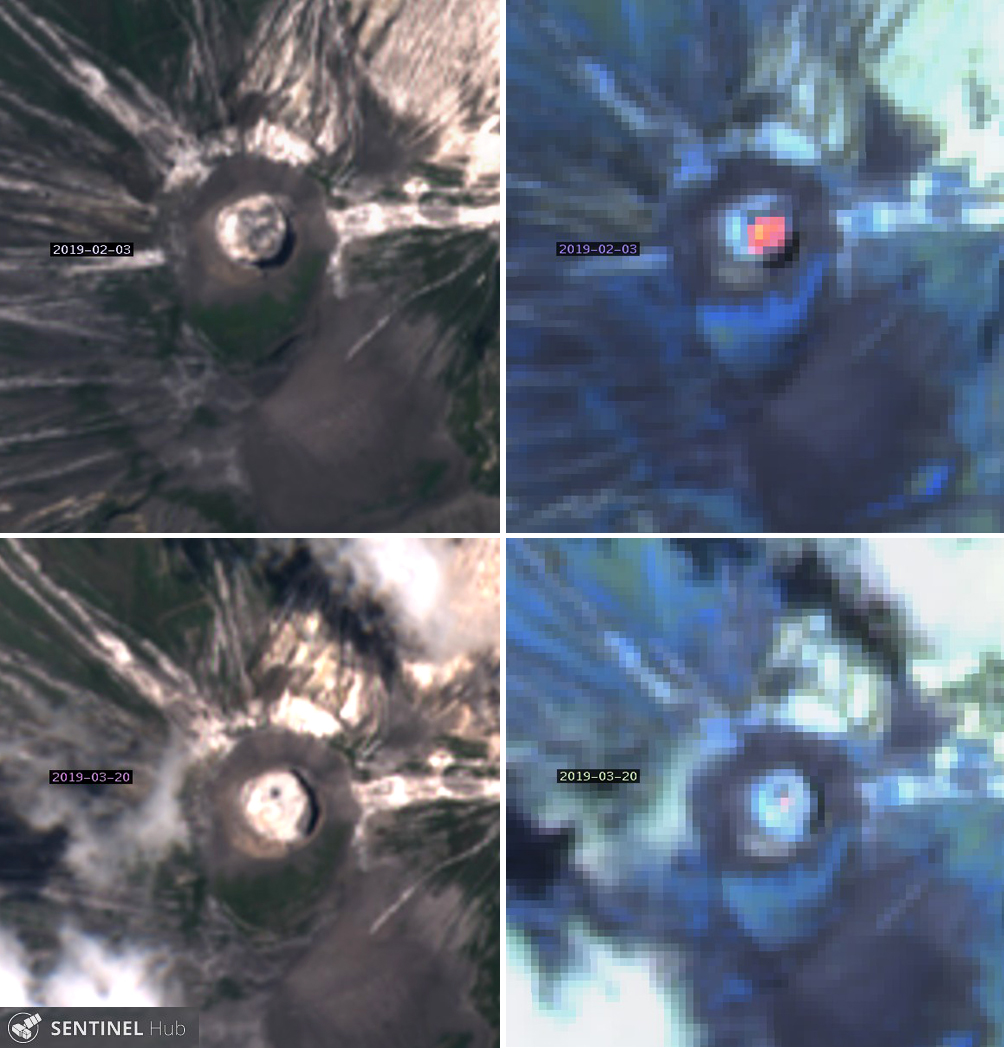

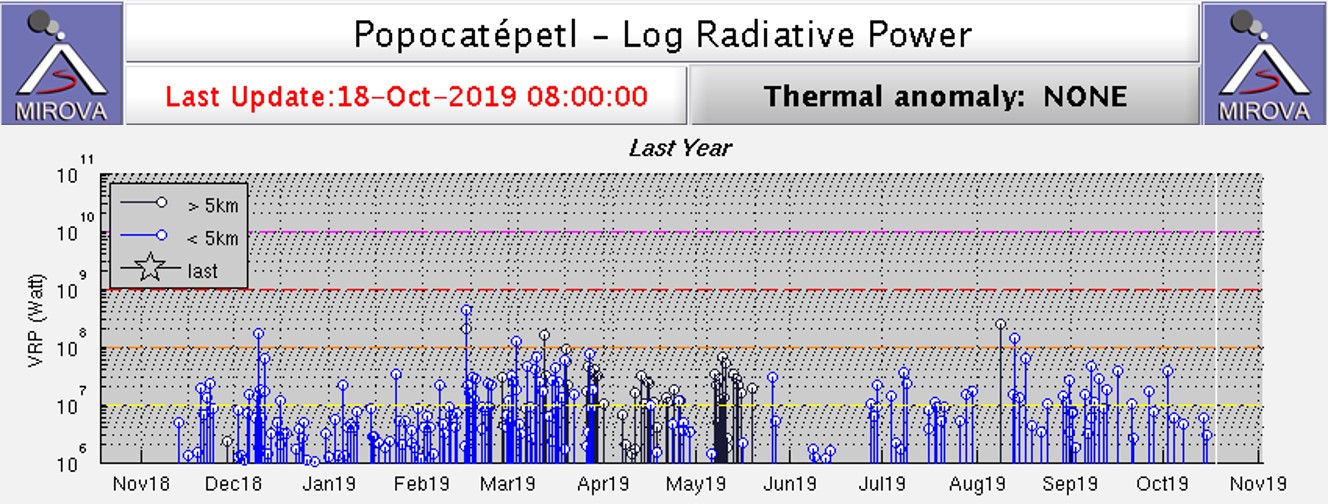

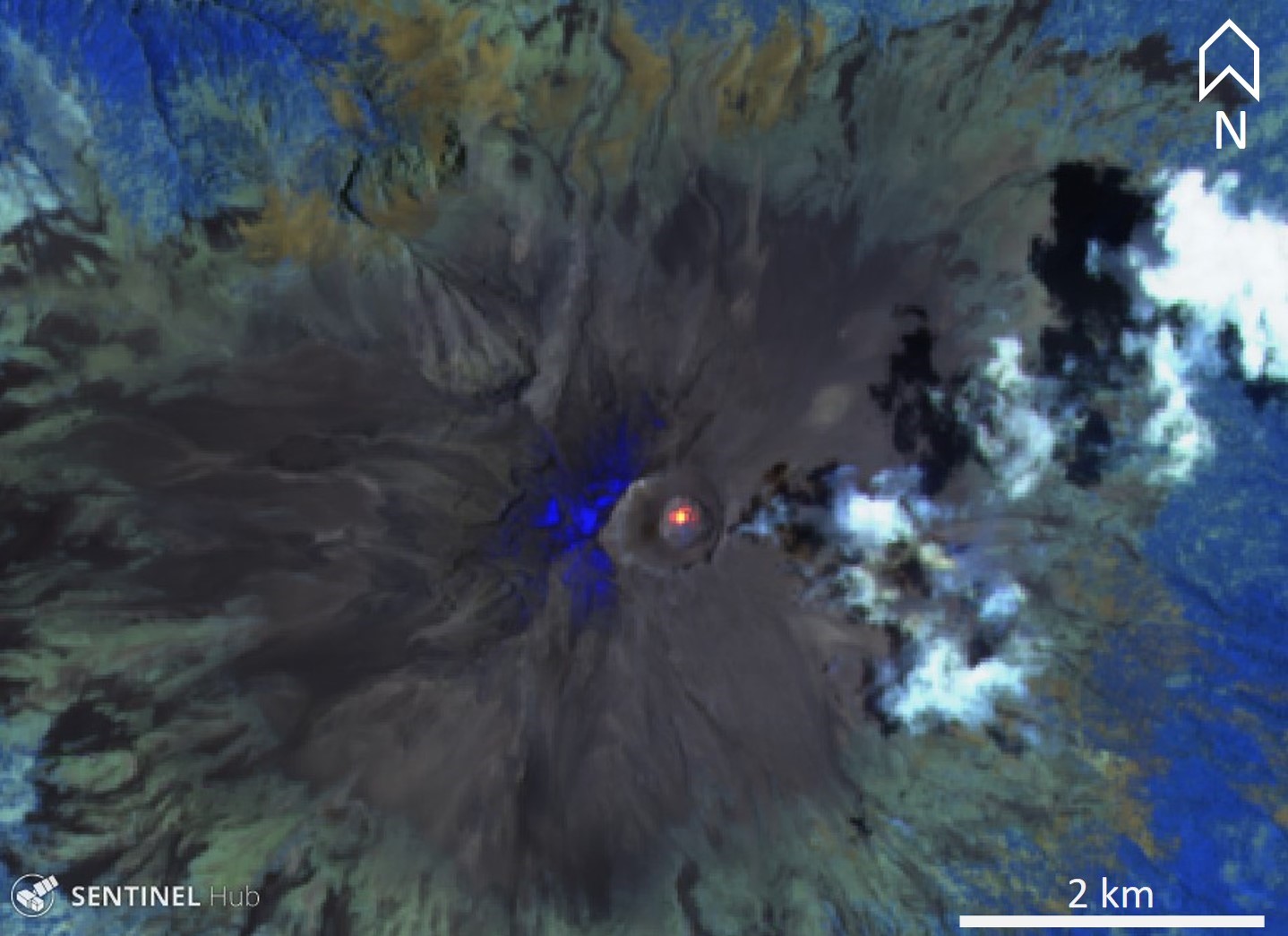

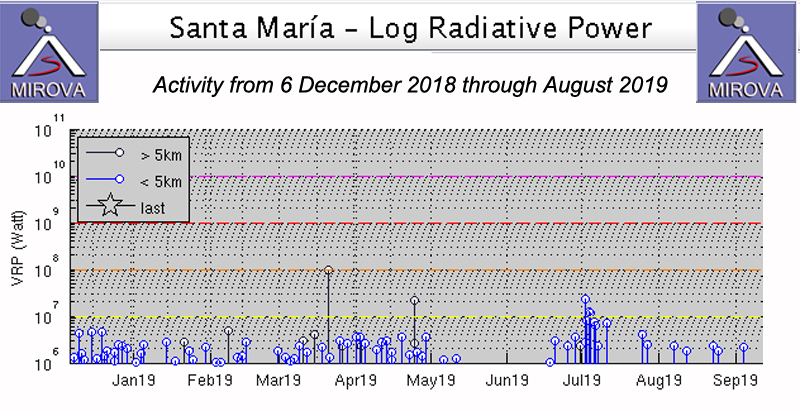

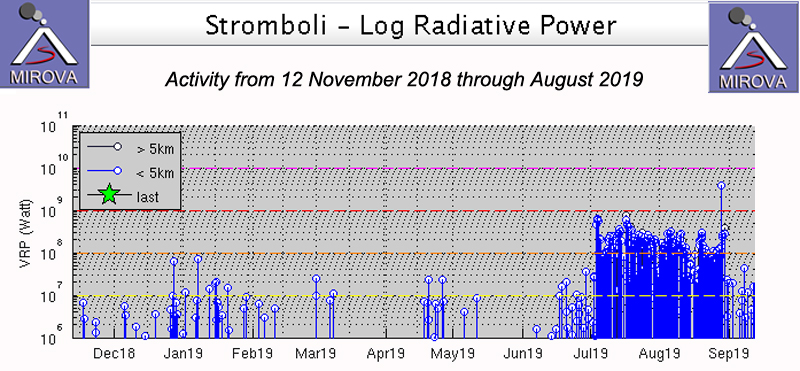

Satellite data. MODIS thermal anomaly data provided through MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) showed frequent low-to-moderate thermal anomalies during the reporting period (figure 225). The intensity of the anomalies was lower compared to previous months. According to data from MODVOLC thermal alerts, a total of ten hotspots were detected at the summit crater on 2 August and 2, 4, 9, 19, and 26 September. Thermal activity in the summit crater was visible in infrared satellite data and was sometimes accompanied by ash plumes, as shown on 17 November (figure 226).

Geologic Background. Volcán Popocatépetl, whose name is the Aztec word for smoking mountain, rises 70 km SE of Mexico City to form North America's 2nd-highest volcano. The glacier-clad stratovolcano contains a steep-walled, 400 x 600 m wide crater. The generally symmetrical volcano is modified by the sharp-peaked Ventorrillo on the NW, a remnant of an earlier volcano. At least three previous major cones were destroyed by gravitational failure during the Pleistocene, producing massive debris-avalanche deposits covering broad areas to the south. The modern volcano was constructed south of the late-Pleistocene to Holocene El Fraile cone. Three major Plinian eruptions, the most recent of which took place about 800 CE, have occurred since the mid-Holocene, accompanied by pyroclastic flows and voluminous lahars that swept basins below the volcano. Frequent historical eruptions, first recorded in Aztec codices, have occurred since Pre-Columbian time.

Information Contacts: Centro Nacional de Prevención de Desastres (CENAPRED), Av. Delfín Madrigal No.665. Coyoacan, México D.F. 04360, México (URL: http://www.cenapred.unam.mx/, Daily Report Archive https://www.gob.mx/cenapred/archivo/articulos); Washington Volcanic Ash Advisory Center (VAAC), Satellite Analysis Branch (SAB), NOAA/NESDIS OSPO, NOAA Science Center Room 401, 5200 Auth Rd, Camp Springs, MD 20746, USA (URL: www.ospo.noaa.gov/Products/atmosphere/vaac, archive at: http://www.ssd.noaa.gov/VAAC/archive.html); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); NASA Global Sulfur Dioxide Monitoring Page, Atmospheric Chemistry and Dynamics Laboratory, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (NASA/GSFC), 8800 Greenbelt Road, Goddard, Maryland, USA (URL: https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Reventador (Ecuador) — January 2024  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Reventador

Ecuador

0.077°S, 77.656°W; summit elev. 3562 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Daily explosions, gas-and-ash emissions, and incandescent avalanches during August-November 2023

Volcán El Reventador, located in Ecuador, is a stratovolcano with a 4-km-wide avalanche scarp open to the E that was formed by edifice collapse. The largest recorded eruption took place in 2002 producing a 17-km-high eruption column, pyroclastic flows that traveled as far as 8 km, and lava flows from summit and flank vents. Recorded eruptions date back to the 16th century and have been characterized by explosive events, lava flows, ash plumes, and lahars. Frequent lahars have built deposits on the scarp slope. The current eruption period began in July 2008 and has recently been characterized daily explosions, gas-and-ash emissions, and block avalanches (BGVN 48:08). This report covers similar activity during August through November 2023 using daily reports from Ecuador's Instituto Geofisico (IG-EPN) and satellite data.

During August through November 2023, IG-EPN reported daily explosions, gas-and-ash plumes that rose as high as 1.3 km above the crater, and frequent crater incandescence, often accompanied by incandescent block avalanches that affected one or multiple flanks. More daily explosions were detected during November, with an average total of 46 per day.

Table 19. Monthly summary of explosions and plume heights recorded at Reventador from August through November 2023. Data could not be collected for 29-30 September 2023 and 6-23 October 2023. Data courtesy of IG-EPN (August-November 2023 daily reports).

| Month |

Average number of explosions per day |

Max plume height above the crater rim (km) |

| Aug 2023 |

32 |

1.3 |

| Sep 2023 |

30 |

1 |

| Oct 2023 |

31 |

1.3 |

| Nov 2023 |

46 |

1.2 |

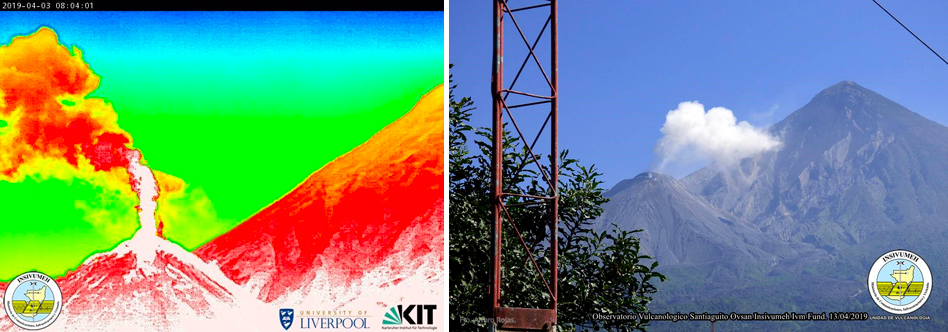

Activity during August consisted of 6-75 daily explosions, nighttime crater incandescence, and incandescent avalanches of material. Frequent seismicity was mainly characterized by long-period (LP) events, harmonic tremor (TRARM), tremor-type (TRE), and volcano tectonic (VT)-type events. Daily gas-and-ash emissions rose 200-1,300 m above the summit and drifted W, SW, NW, NE, N, and E, based on webcam and satellite images. The Washington VAAC also reported occasional ash plumes that rose 400-1,600 m above the crater and drifted NW. Avalanches of incandescent material were reported during 1-2, 6-7, 9-14, 16-17, 18-21, and 26-29 August, which traveled 500-900 m below the crater and affected multiple flanks (figure 180). During 24-25 August incandescent material was ejected 300 m above the crater.

Gas-and-ash emissions and seismicity characterized by LP, VT, TRARM, and TRE-type events continued during September; data were not available for 29-30 September. Daily gas-and-ash emissions rose 200-1,000 m above the crater and generally drifted W, NW, and SW (figure 181). Near-daily explosions ranged from 16-53 per day, often accompanied by incandescent avalanches, which affected one or multiple flanks and traveled 100-800 m below the crater. During 2-3 September incandescent material was ejected 200 m above the crater and was accompanied by blocks rolling down the flanks. During 16-17 September incandescent material was ejected 100-200 m above the crater and avalanches descended 600 m below the crater. During 21-22 and 24-26 September incandescent material was ejected 100-300 m above the crater. According to the Washington VAAC, ash plumes rose 700 m above the crater and drifted SW, W, and NW on 3, 16, and 20 September, respectfully.

During October, daily explosions, gas-and-ash plumes, and crater incandescence continued, with 16-40 explosions recorded each day (figure 182); data was not available for 6-23 October. Seismicity consisted of LP, TRE, and TRARM-type events. Gas-and-ash emissions rose 200-1,000 m above the crater and drifted W, SW, NW, SSW, NNW, and NE. The Washington VAAC reported that ash plumes rose 1-1.3 km above the crater and drifted W, SW, and NW during 1-5 October. During 30 September-1 October incandescent avalanches descended 700 m below the crater. Ejected material rose 200 m above the crater during 2-5 October and was accompanied by avalanches of material that traveled 250-600 m below the crater rim; incandescent avalanches were also reported during 23-29 October.

Daily explosions, LP, TRARM, VT, and TRE-type events, crater incandescence, and avalanches of material continued during November. There were 26-62 daily explosions detected throughout the month. Gas-and-ash emissions rose 300-1,200 m above the crater and drifted in different directions (figure 183). The Washington VAAC reported that ash plumes rose 700-1,620 m above the crater and drifted NW, W, WNW, SW, E, SE, and ESE. Frequent incandescent avalanches descended 500-1,000 m below the crater. Explosions ejected material 100-300 m above the crater during 4-7, 11-12, and 19-23 November.

Satellite data. MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) analysis of MODIS satellite data showed intermittent thermal anomalies of low-to-moderate power (figure 184). Thermal activity mainly consisted of incandescent avalanches descending the flanks due to the frequently detected explosions. The MODVOLC hotspot system identified a total of ten hotspots on 3 August, 7, 18, 12, 22, and 28 September, and 7, 9, and 19 November.

Geologic Background. Volcán El Reventador is the most frequently active of a chain of Ecuadorian volcanoes in the Cordillera Real, well east of the principal volcanic axis. The forested, dominantly andesitic stratovolcano has 4-km-wide avalanche scarp open to the E formed by edifice collapse. A young, unvegetated, cone rises from the amphitheater floor to a height comparable to the rim. It has been the source of numerous lava flows as well as explosive eruptions visible from Quito, about 90 km ESE. Frequent lahars in this region of heavy rainfall have left extensive deposits on the scarp slope. The largest recorded eruption took place in 2002, producing a 17-km-high eruption column, pyroclastic flows that traveled up to 8 km, and lava flows from summit and flank vents.

Information Contacts: Instituto Geofísico, Escuela Politécnica Nacional (IG-EPN), Casilla 17-01-2759, Quito, Ecuador (URL: http://www.igepn.edu.ec/); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/).

Erta Ale (Ethiopia) — January 2024  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Erta Ale

Ethiopia

13.601°N, 40.666°E; summit elev. 585 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Strong lava lake activity and lava overflows during June-November 2023

Erta Ale in Ethiopia has a 50-km-wide edifice that rises more than 600 m from below sea level in the Danakil depression. The summit caldera is 0.7 x 1.6 km and contains at least two pit craters (North and South). Another larger 1.8 x 3.1-km-wide depression is located SE of the summit and is bounded by curvilinear fault scarps on the SE side. Lava flows from fissures have traveled into the caldera and locally overflowed the crater rim. The current eruption has been ongoing since 1967, with at least one long-term active lava lake present in the summit caldera. Recent fissure eruptions from 2017 have occurred on the SE flank (BGVN 42:07). Recent activity has been characterized by minor thermal activity at the S crater and an active lava lake at the N crater (BGVN 48:06). This report covers strong lava lake activity primarily at the N pit crater during June through November 2023 using information from satellite infrared data.

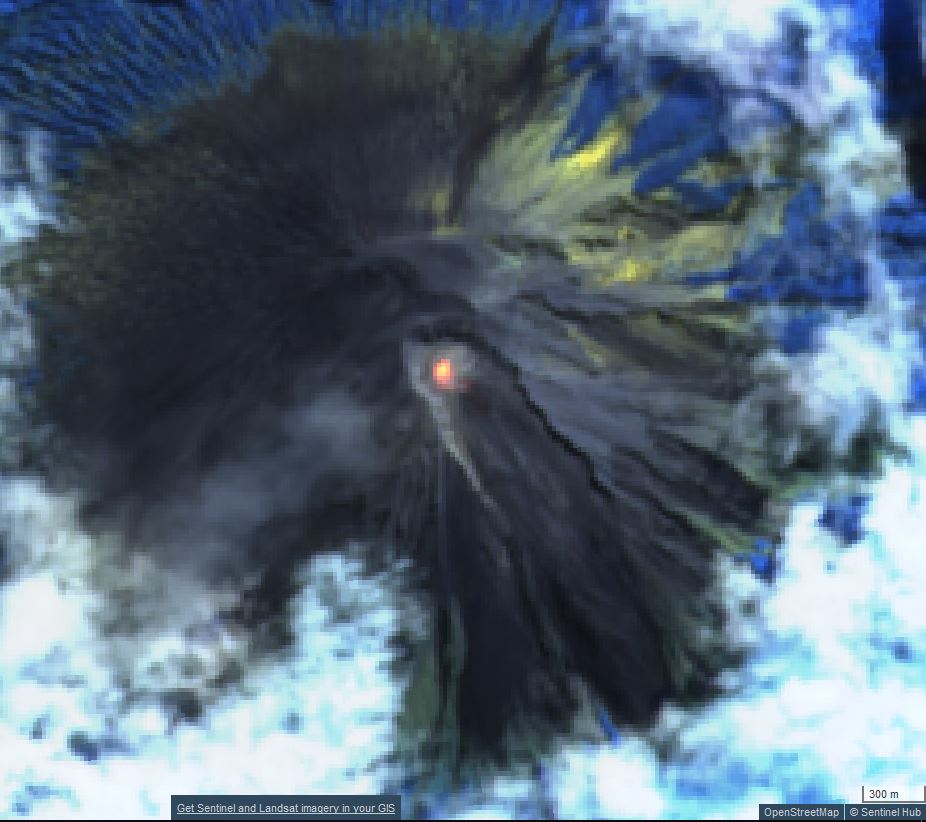

Infrared satellite images generally showed an active lava lake as the N pit crater and variable thermal activity at the S pit crater during the reporting period. On 7 June two strong thermal anomalies were detected at the S pit crater and two weaker anomalies were visible at the N pit crater. Those anomalies persisted throughout the month, although the intensity at each declined. On 2 July a possible lava lake was identified at the S pit crater, filling much of the crater. On 7 July both pit craters contained active lava lakes (figure 120). By 12 July the thermal activity decreased; two smaller anomalies were visible through the rest of the month at the S pit crater while the N pit crater showed evidence of cooling.

Renewed lava lake activity was identified at the N pit crater, based on a satellite image from 11 August, with two smaller anomalies visible at the S pit crater. By 16 August the lava lake in the N pit had begun to cool and only a small thermal anomaly was identified. Activity restarted on 21 August, filling much of the E and SE part of the N pit crater. The thermal activity at the N pit crater intensified on 31 August, particularly in the NW part of the crater. On 5 September lava filled much of the N pit crater, overflowing to the W and SW. During at least 10-20 September thermal activity at both craters were relatively low.

According to a satellite image on 25 September, strong thermal activity resumed when lava overflowed the N pit crater to the S, SW, and NE (figure 120). A satellite image taken on 5 October showed lava flows from the N had spilled into the S and begun to cool, accompanied by two weak thermal anomalies at the S pit crater. On 15 October lava flows again traveled SE and appeared to originate from the S pit crater (figure 120). Following these events, smaller thermal anomalies were visible on the SE rim of the N pit crater and within the S pit crater.

Lava was visible in the NW part of the N pit crater according to a satellite image taken on 4 November. By 9 November the intensity had decreased, and the lava appeared to cool through the rest of the month; young lava flows were visible along the W side of the S pit crater on 24 and 29 November. Lava flows occurred at the N pit crater trending NE-SW and along the E side on 29 November (figure 120).

During the reporting period, the MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) thermal detection system recorded consistent activity during the first half of 2023 (figure 121). Beginning in June 2023, thermal activity increased and remained variable in intensity through the end of the year indicating the presence of an active lava lake and lava flows. The MODVOLC thermal detection system registered a total of 63 anomalies during 7, 8, and 23 July, 10 and 18 August, 3, 5, 16, 23, 24, and 25 September, 15 and 20 October, and 21, 24, 26, 28, and 30 November. Some of these stronger thermal anomalies were also detected in Sentinel-2 infrared satellite images that showed an active lava lake at the N pit crater and subsequent lava overflows from both pit craters (figure 120).

Geologic Background. The Erta Ale basaltic shield volcano in Ethiopia has a 50-km-wide edifice that rises more than 600 m from below sea level in the Danakil depression. The volcano includes a 0.7 x 1.6 km summit crater hosting steep-sided pit craters. Another larger 1.8 x 3.1 km wide depression elongated parallel to the trend of the Erta Ale range is located SE of the summit and is bounded by curvilinear fault scarps on the SE side. Basaltic lava flows from these fissures have poured into the caldera and locally overflowed its rim. The summit caldera usually also holds at least one long-term lava lake that has been active since at least 1967, and possibly since 1906. Recent fissure eruptions have occurred on the N flank.

Information Contacts: MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Ubinas

Peru

16.345°S, 70.8972°W; summit elev. 5608 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

New eruption with explosions and ash plumes during June-December 2023

Ubinas, located in Peru, has had 24 eruptions since 1550, which more recently have been characterized by explosions, ash plumes, and lahars (BGVN 45:03). This report covers a new eruption during June through December 2023 based on reports from Instituto Geofisico del Peru (IGP), Instituto Geológico Minero y Metalúrgico (INGEMMET), and satellite data.

IGP reported that seismic unrest began on 17 May, followed by an increase in seismicity during the second half of the month. There were 168 volcano-tectonic (VT) earthquakes detected, which are associated with rock fracturing processes, and 171 long-period (LP) earthquakes recorded during 16-24 May, which are associated with the movement of volcanic fluid.

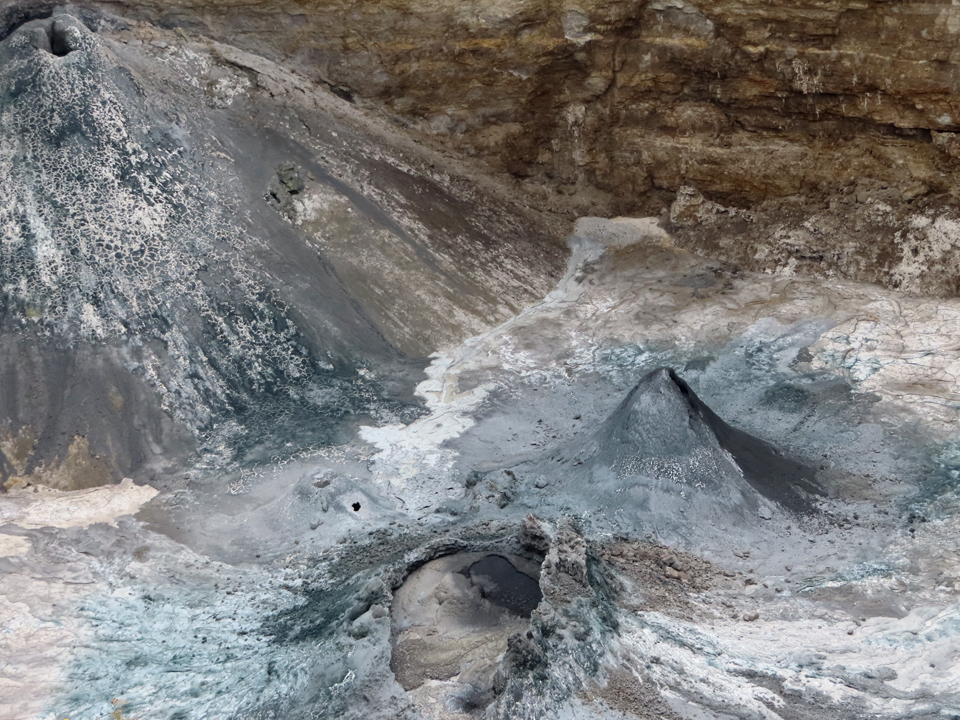

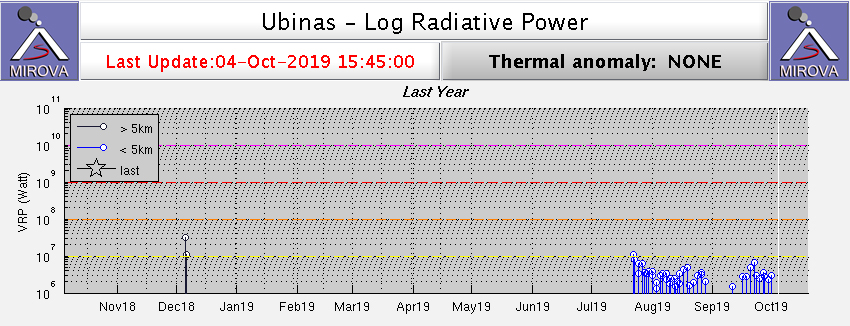

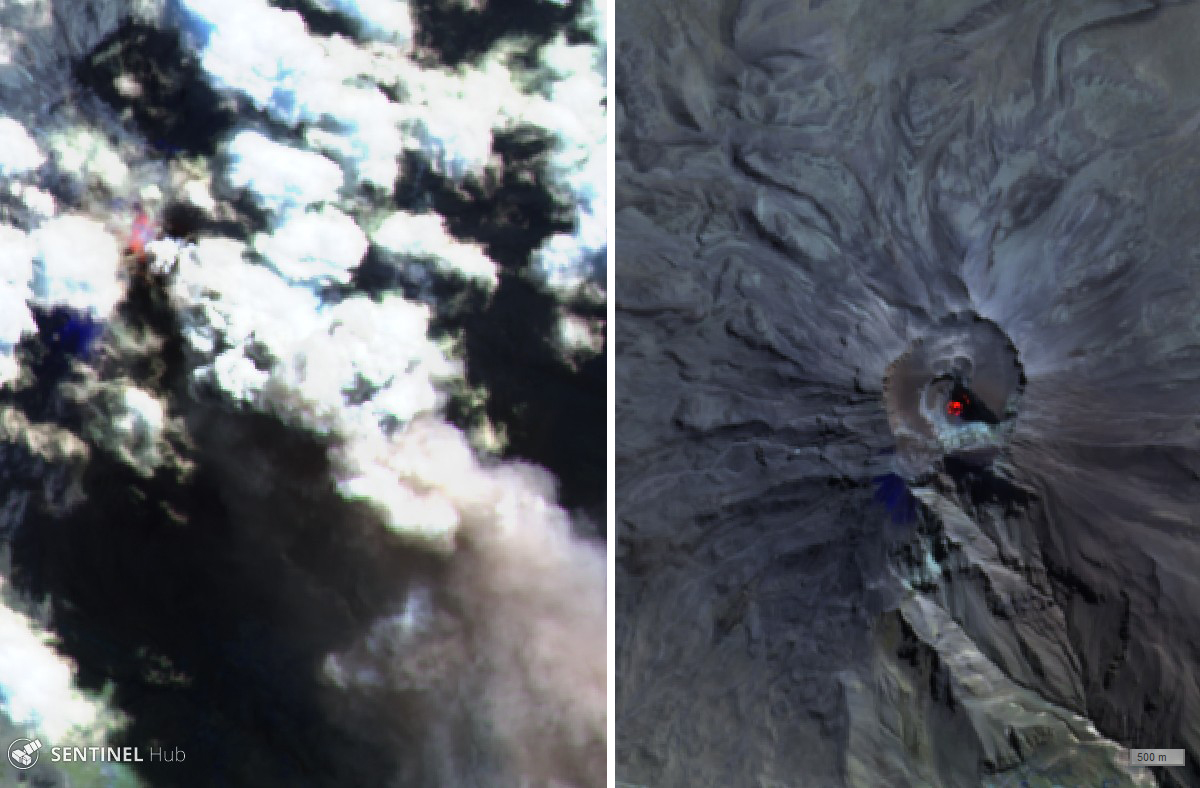

Seismicity and fumarolic activity at the crater level continued to increase during June. During 1-18 June there was an average of 631 VT-type earthquakes and 829 LP earthquakes recorded. Webcams showed gas-and-steam emissions rising 500 m above the summit and drifting SE. In addition, the maximum value of emitted sulfur dioxide during this period was 337 tons/day. During 19-22 June an average of 315 VT-type events and 281 LP-type events and tremor were reported. On 20 June the Gobierno Regional de Moquegua raised the Volcano Alert Level (VAL) to Yellow (the second level on a four-color scale), based on recommendations from IGP. Webcam images showed ash emissions rising 1 km above the summit and drifting E at 0011 on 22 June, which IGP reported marked the start of a new eruption. Sporadic and diffuse gas-and-ash emissions continued to rise 800-1,500 m above the summit through the rest of the month and drifted mainly E, N, NW, W, SW, and NE. During 23-25 June there was an average of 402 VT-type earthquakes and 865 LP-type events detected. During 26-28 June the earthquakes associated with ash emissions, which have been observed since 22 June, decreased, indicating the end of the phreatic phase of the eruption, according to IGP. A thermal anomaly was detected in the crater for the first time on 26 June and was periodically visible through 4 July (figure 61). During 29-30 June there was an average of 173 VT-type earthquakes and 351 LP-type events recorded, and sulfur dioxide values ranged between 600 t/d and 1,150 t/d. During this same time, seismicity significantly increased, with 173 VT-type earthquakes, 351 LP-type events, and harmonic tremor which signified rising magma. The Gobierno Regional de Moquegua raised the Alert Level to Orange (the third level on a four-color scale) on 30 June based on the recommendation from IGP and INGEMMET.

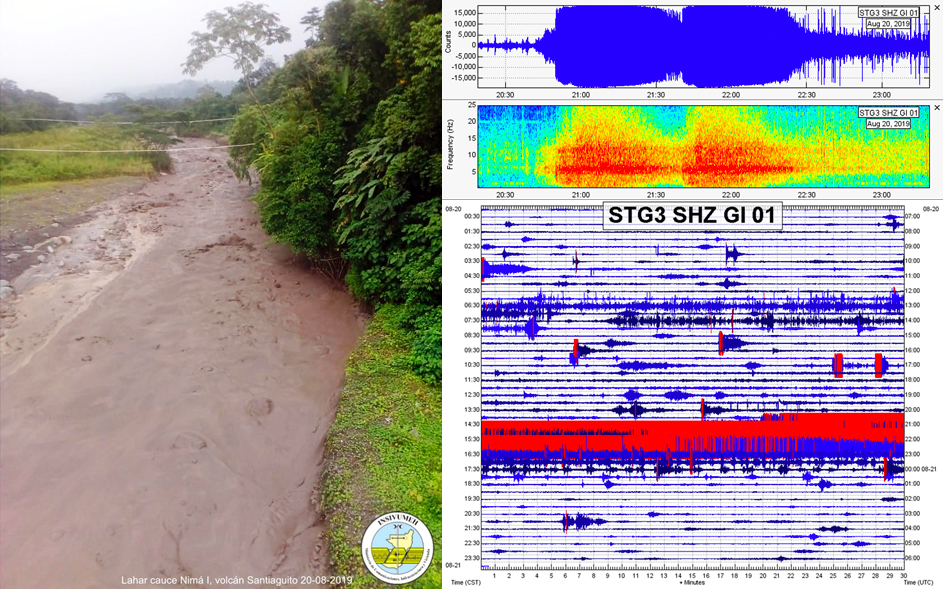

Activity during July consisted of continued seismicity and gas-and-ash emissions. Gas-and-ash emissions rose as high as 5 km above the summit and drifted as far as 40 km in different directions during 1, 4-6, 16, 20-23, 26, and 29 July, based on webcam and satellite images. During 1-2 July an average of 72 VT-type earthquakes and 114 LP-type events were detected. In addition, during that time, ashfall was reported in Ubinas (6.5 km SSE) and Querapi (4.5 km SE). During 2-3 July INGEMMET reported gas-and-ash plumes rose 400 m above the summit and drifted SW, causing ashfall in downwind areas as far as 5 km. During 3-4 July there was an average of 69 VT-type earthquakes and 96 LP-type events reported. On 4 July starting around 0316 there were 16 seismic signals associated with explosive activity and ash emissions detected (figure 62). According to INGEMMET an explosion ejected ballistics and generated a gas-and-ash plume that rose 5.5 km above the summit and drifted SW and S. Ashfall was recorded in Querapi, Ubinas, Sacohaya (7 km SSE), Anascapa (11 km SE), San Miguel (10 km SE), Tonohaya (7 km SSE), Huatahua, Huarina, Escacha (9 km SE), and Matalaque (17 km SSE), and was most significant within 5 km of the volcano. IGP noted that ash fell within a radius of 20 km and deposits were 1 mm thick in towns in the district of Ubinas.

During 5-9 July an average of 67 VT-type events and 47 LP-type events were reported. A period of continuous gas-and-ash emissions occurred on 5 July, with plumes drifting more than 10 km SE and E. A total of 11 seismic signals associated with explosions also detected on 6, 16, 17, and 22 July. On 6 July explosions recorded at 0747 and 2330 produced gas-and-ash plumes that rose as high as 3.5 km above the summit and drifted as far as 30 km NW, NE, SE, and S. According to the Washington VAAC the explosion at 0747 produced a gas-and-ash plume that rose to 9.1 km altitude and drifted SW, which gradually dissipated, while a lower-altitude plume rose to 7.6 km altitude and drifted NE. Gobierno Regional de Moquegua declared a state of emergency for districts in the Moquegua region, along with Coalaque Chojata, Icuña, Lloque, Matalaque, Ubinas, and Yunga of the General Sánchez Cerro province, to be in effect for 60 days. On 7 July an ash plume rose to 7.3 km altitude and drifted E at 0320. At 0900 and 1520 gas-and-steam plumes with diffuse ash rose to 6.7 km altitude and drifted SE. Small ash emissions were visible in satellite and webcam images at 0920 and 1520 on 8 July and rose as high as 6.4 km altitude and drifted SE. During 10-16 July there was an average of 80 VT-type earthquakes and 93 LP-type events reported. INGEMMET reported that during 9-11 July sulfur dioxide emissions were low and remained around 300 t/d.

During 17-23 July an average of 46 VT-type events and 122 LP-type events were detected. On 20 July at 0530 an explosion generated an ash plume that rose 3-4.5 km above the crater and drifted 65 km toward Arequipa. An explosion on 21 July at 0922 produced a gas-and-ash plume that rose 5 km above the summit (figure 63). Ashfall was reported in Querapi, Ubinas, Tonohaya, Anascapa, Sacohaya, San Miguel, Escacha, Huatagua (14 km SE), Huarina, Escacha (9 km SE), Matalaque, Logén, Santa Lucía de Salinas, and Salinas de Moche. An explosion on 22 July at 1323 generated an ash plume that rose 5.5 km above the summit and drifted NE, E, and SE. During 24-30 July there were five volcanic explosions detected and an average of 60 VT-type events and 117 LP-type events. An explosion on 29 July at 0957 produced an ash plume that rose 2.5 km above the summit and drifted as far as 40 km NE, E, and SE. As a result, significant ashfall was reported in Ubinas and Matalaque.

During August, explosions, gas-and-ash emissions, and seismic earthquakes persisted. During 31 July to 6 August there was an average of 115 VT-type events and 124 LP-type events reported. Gas-and-ash emissions were observed during 1, 6, 10, 13-14, 17-18, 21, and 23 August and they drifted as far as 20 km in different directions; on 14 and 18 August continuous ash emissions extended as far as 40 km S, SE, and NE. An explosion was detected at 2110 on 1 August, which generated a gas-and-ash plume that rose 5.4 km above the summit and drifted SE and E. The explosion ejected blocks and incandescent material as far as 3 km from the crater onto the SW, S, and SE flanks. Ashfall was reported in Ubinas and Chojata (19 km ESE). Gas-and-ash emissions rose as high as 2 km above the summit and drifted in different directions through 5 August, sometimes causing ashfall within a 15-km-radius. An explosion at 0009 on 6 August ejected blocks and produced a gas-and-ash plume that rose 1.4 km above the summit and drifted SE and E, which caused ashfall in Ubinas and Chojata and other areas within a 30-km radius. During 7-13 August there was an average of 102 VT-type events and 60 LP-type events detected. INGEMMET reported that sulfur dioxide emissions were low on 7 August and averaged 400 t/d.

One volcanic explosion that was recorded on 10 August, producing gas-and-ash emissions that rose 2.4 km above the summit and drifted as far as 25 km SE and E. Ashfall was observed in Ubinas, Matalaque, and Chojata. During 10-11 and 13-14 August sulfur dioxide values increased slightly to moderate levels of 2,400-3,700 t/d. The average number of VT-type events was 104 and the number of LP-type events was 71 during 14-21 August. Two explosions were detected at 0141 and 0918 on 21 August, which produced gas-and-ash emissions that rose 3.5 km above the summit and drifted 50 km N, NE, W, and NW (figure 64). The explosion at 0918 generated an ash plume that caused ashfall in different areas of San Juan de Tarucani. During 22-27 August the average number of VT-type events was 229 and the average number of LP-type events was 54. An explosion was reported at 1757 on 25 August, which generated a gas-and-ash plume that rose 4.2 km above the summit and drifted in multiple directions as far as 25 km. During 28 August through 3 September gas-and-ash emissions rose 600 m above the summit and drifted as far as 5 km E and SE. During this time, there was an average of 78 VT-type events and 42 LP-type events.

Gas-and-steam emissions rose 600-2,600 m above the summit and drifted as far as 15 km in multiple directions during September. During 4-10 and 11-17 September there was an average of 183 VT-type events and 27 LP-type events, and 114 VT-type events and 86 LP-type events occurred, respectively. On 14 September an explosion at 1049 generated a gas-and-ash plume that rose 2.6 km above the summit and drifted as far as 15 km E, NE, SE, and S (figure 65). During 14-16 September an average of three hours of seismic tremor related to ash emissions was recorded each day. During 18-24 September the average number of VT-type events was 187 and the average number of LP-type events was 45. During 25 September and 1 October, there was an average number of 129 VT-type events and 52 LP-type events detected.

Relatively low activity was reported during October; during 2-9 October there was an average number of 155 VT-type events and 27 LP-type events recorded. On 1 October at 1656 seismic signals associated with ash emissions were recorded for an hour and thirty minutes; the ash plumes rose as high as 1 km above the summit and drifted more than 10 km E, S, and SW. On 4 October IGP reported that an ash plume drifted more than 15 km SW and S. Sulfur dioxide emissions were 1,250 t/d on that day. On 7 October a gas-and-ash plume rose 1.9 km above the summit and drifted NE, E, and SE. On 4 October the amount of sulfur dioxide emissions was 1,250 t/d. During 10-15 October there was an average number of 225 VT-type events and 34 LP-type events recorded. On 11 October at 1555 a single seismic signal associated with an ash pulse was recorded; the gas-and-ash emissions rose 700 m above the summit and drifted SW and W. There was an average of 204 VT-type events and 25 LP-type events detected during 16-22 October and 175 VT-type events and 17 LP-type events during 23-29 October. On 27 October at 0043 a gas-and-ash emission rose 500 m above the summit and drifted SE and E. A minor thermal anomaly was visible on the crater floor. During 30 October to 5 November there was an average of 95 VT-type events and 24 LP-type events detected.

Activity remained relatively low during November and December and consisted mainly of gas-and-steam emissions and seismicity. Gas-and-steam emissions rose 900-1,100 m above the summit and drifted mainly E, SE, N, and NE. IGP detected an average of 166 VT-type events and 38 LP-type events during 6-15 November, 151 VT-type events and 17 LP-type events during 16-30 November, 143 VT-type events and 23 LP-type events during 1-15 December, and 129 VT-type events and 21 LP-type events during 16-31 December. No explosions or ash emissions were recorded during November. The VAL was lowered to Yellow (the second level on a four-color scale) during the first week of November. According to the Washington VAAC an ash emission was identified in a satellite image at 0040 on 11 December that rose to 5.5 km altitude and drifted NW. Webcam images at 0620 and 1220 showed continuous gas-and-steam emissions possibly containing some ash rising as high as 7 km altitude. Webcam images during 10-31 December showed continuous gas-and-ash emissions that rose as high as 2.5 km above the summit and drifted up to 5 km NW, W, and SW. On 12 December continuous ash emissions drifted more than 10 km N and NW.

Geologic Background. The truncated appearance of Ubinas, Perú's most active volcano, is a result of a 1.4-km-wide crater at the summit. It is the northernmost of three young volcanoes located along a regional structural lineament about 50 km behind the main volcanic front. The growth and destruction of Ubinas I was followed by construction of Ubinas II beginning in the mid-Pleistocene. The upper slopes of the andesitic-to-rhyolitic Ubinas II stratovolcano are composed primarily of andesitic and trachyandesitic lava flows and steepen to nearly 45°. The steep-walled, 150-m-deep summit crater contains an ash cone with a 500-m-wide funnel-shaped vent that is 200 m deep. Debris-avalanche deposits from the collapse of the SE flank about 3,700 years ago extend 10 km from the volcano. Widespread Plinian pumice-fall deposits include one from about 1,000 years ago. Holocene lava flows are visible on the flanks, but activity documented since the 16th century has consisted of intermittent minor-to-moderate explosive eruptions.

Information Contacts: Instituto Geofisico del Peru (IGP), Calle Badajoz N° 169 Urb. Mayorazgo IV Etapa, Ate, Lima 15012, Perú (URL: https://www.gob.pe/igp); Observatorio Volcanologico del INGEMMET (Instituto Geológical Minero y Metalúrgico), Barrio Magisterial Nro. 2 B-16 Umacollo - Yanahuara Arequipa, Peru (URL: http://ovi.ingemmet.gob.pe); Gobierno Regional Moquegua, Sede Principal De Moquegua, R377+5RR, Los Chirimoyos, Moquegua 18001, Peru (URL: https://www.gob.pe/regionmoquegua); Washington Volcanic Ash Advisory Center (VAAC), Satellite Analysis Branch (SAB), NOAA/NESDIS OSPO, NOAA Science Center Room 401, 5200 Auth Rd, Camp Springs, MD 20746, USA (URL: www.ospo.noaa.gov/Products/atmosphere/vaac, archive at: http://www.ssd.noaa.gov/VAAC/archive.html); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Kanaga (United States) — January 2024  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Kanaga

United States

51.923°N, 177.168°W; summit elev. 1307 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Small explosion on 18 December 2023

Kanaga lies within the Kanaton caldera at the northern tip of Kanaga Island. The caldera rim forms a 760-m-high arcuate ridge south and east of Kanaga; a lake occupies part of the SE caldera floor. Most of its previous recorded eruptions are poorly documented, although they date back to 1763. Fumarolic activity at Kanaga occurs in a circular, 200-m-wide, 60-m-deep summit crater and produces vapor plumes sometimes seen on clear days from Adak, 50 km to the east. Its most recent eruption occurred in February 2012, which consisted of numerous small earthquakes, a possible weak ash cloud, and gas-and-steam emissions (BGVN 38:03). This report covers a new eruption during December 2023, based on information from the Alaska Volcano Observatory (AVO).

A small explosion was detected in local infrasound and seismic data at 2231 on 18 December, followed by elevated seismicity. No ash emissions were visible in partly cloudy satellite images. On 19 December the Volcano Alert Level (VAL) was raised to Advisory (the second level on a four-level scale) and the Aviation Color Code (ACC) was raised to Yellow (the second color on a four-color scale). The rate of seismicity significantly declined after the 18th, although it remained elevated through 30 December. Small, daily earthquakes occurred during 19-28 December. Satellite observations following the event showed a debris flow extending 1.5 km down the NW flank. Possible minor gas-and-steam emissions were visible in a webcam image on 20 December. Weakly elevated surface temperatures were identified in satellite data during 23-26 December. A series of cracks extending from the inner crater to the upper SE flank and debris deposits on the upper flanks were observed in satellite images on 27 December. AVO reported that these were likely formed during the 18 December event. Local webcam and seismic data were temporarily offline due to a power failure during 4-28 January.

On 28 January connection to the seismic stations and webcams was restored and webcam images showed gas-and-steam emissions at the summit. Occasional earthquakes were also detected each day. A period of weak seismic tremor was observed on 31 January. During February, the number of earthquakes declined. On 27 February AVO lowered the VAL to Normal (the lowest level on a four-level scale) and the ACC to Green (the lowest color on a four-color scale) due to decreased levels of seismicity and no new surface changes or elevated temperatures based on satellite and webcam data.

Geologic Background. Symmetrical Kanaga stratovolcano is situated within the Kanaton caldera at the northern tip of Kanaga Island. The caldera rim forms a 760-m-high arcuate ridge south and east of Kanaga; a lake occupies part of the SE caldera floor. The volume of subaerial dacitic tuff is smaller than would typically be associated with caldera collapse, and deposits of a massive submarine debris avalanche associated with edifice collapse extend nearly 30 km to the NNW. Several fresh lava flows from historical or late prehistorical time descend the flanks of Kanaga, in some cases to the sea. Historical eruptions, most of which are poorly documented, have been recorded since 1763. Kanaga is also noted petrologically for ultramafic inclusions within an outcrop of alkaline basalt SW of the volcano. Fumarolic activity occurs in a circular, 200-m-wide, 60-m-deep summit crater and produces vapor plumes sometimes seen on clear days from Adak, 50 km to the east.

Information Contacts: Alaska Volcano Observatory (AVO), a cooperative program of a) U.S. Geological Survey, 4200 University Drive, Anchorage, AK 99508-4667 USA (URL: https://avo.alaska.edu/), b) Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, PO Box 757320, Fairbanks, AK 99775-7320, USA, and c) Alaska Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys, 794 University Ave., Suite 200, Fairbanks, AK 99709, USA (URL: http://dggs.alaska.gov/).

Klyuchevskoy (Russia) — January 2024  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Klyuchevskoy

Russia

56.056°N, 160.642°E; summit elev. 4754 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

New eruption consisting of Strombolian activity, lava flows and fountains, and ash plumes during June-December 2023

Klyuchevskoy, located on the Kamchatka Peninsula, has produced frequent moderate-volume explosive and effusive eruptions and more than 100 flank eruptions have occurred during the past 3,000 years. Eruptions recorded since the late 17th century have resulted in frequent changes to the morphology of the 700-m-wide summit crater. Eruptions over the past 400 years have primarily originated from the summit crater, although numerous major explosive and effusive eruptions have also occurred from flank craters. The previous eruption ended in November 2022 and consisted of Strombolian activity (BGVN 47:12). This report covers a new eruption during June through December 2023, characterized by Strombolian explosions, lava flows, and ash plumes. Information primarily comes from weekly and daily reports from the Kamchatkan Volcanic Eruption Response Team (KVERT) and various satellite data.

KVERT reported that a Strombolian eruption began at 2323 on 22 June. A thermal anomaly was visible in satellite data starting on 22 June (figure 75). As a result, the Aviation Color Code (ACC) was raised to Yellow (the second lowest level on a four-color scale). During 4-6 and 13 July small ash clouds were occasionally observed over the crater. On 19 July a new lava flow began to effuse along the Apakhonchich drainage on the SE flank, which continued through 19 August. Lava fountaining was reported on 21 July in addition to the active lava flow, which continued through 23 August and during 27-30 August. During 22-23 and 27-30 August the lava flow was active along the Apakhonchich drainage on the SE flank.

Similar activity was observed during September. Lava fountaining resumed on 2 September and continued through 31 October. In addition, on 2 September a lava flow began to effuse along the Kozyrevsky drainage on the SW flank. During 3-5 September resuspended ash plumes rose to 3-3.5 km altitude and extended as far as 170 km E by 1940 on 4 September. The ACC was raised to Orange (the third level on a four-color scale) at 1240 on 4 September. The ACC was briefly lowered back to Yellow at 1954 that same day before returning to Orange during 1532-1808 on 5 September due to resuspended ash plumes that rose to 3 km altitude and drifted 120 km E at 1500. KVERT reported that Strombolian activity continued, feeding the lava flows advancing down the Apakhonchichsky and Kozyrevsky drainages through most of the month. During 25 September through 16 October the lava flow was only active in the Apakhonchichisky drainage (figure 76). During 9-12 September resuspended ash plumes rose to 1.5-4 km altitude and extended 550 km E and SE. On 22 September resuspended ash plumes rose to 2-2.5 km altitude and drifted 50-90 km E, which prompted KVERT to raise the ACC to Orange; the ACC was lowered back to Yellow on 24 September. On 29 September phreatic explosions generated ash plumes that rose to 5.2-5.3 km altitude.

Activity during October continued with lava fountains, lava flows, and ash plumes. Strombolian activity with lava fountains continued at the crater and active lava flows alternately descended the Apakhonchichisky and Kozyrevsky drainages on the SE and S flanks (figure 77). During 11-12 October gas-and-steam plumes containing some ash rose to 5.5-6 km altitude and extended as far as 65 km NE and SE. The ACC was raised to Orange on 11 October. According to observers at the Kamchatka Volcanological Station, lava effusion was almost continuous, and incandescent material was ejected as high as 300 m above the crater rim. On 13 October at 1420 an ash plume rose to 5-5.5 km altitude and drifted 90-100 km SE. During 14-16 October gas-and-steam plumes containing some ash rose to 4-6 km altitude and drifted 40-145 km ESE and E. On 16 October lava on the SE flank melted the snow and ice, causing phreatic explosions and large collapses of material from the margins of the flow. At 1500 an ash plume rose to 6.5-7 km altitude and drifted 70 km ENE. On 17 October an ash plume was reported extending 360 km NE. Gray-red ashfall was observed in Klyuchi at 0700; this ash was resuspended from older material.

During 22-31 October phreatic explosions generated ash plumes mainly containing ash from collapses of previously deposited pyroclastic material that rose to 7 km altitude and extended as far as 280 km NE, E, SW, and S on 23 and 29 October the ash plumes rose to 8 km altitude. Ash plumes during 27-29 October rose to 8 km altitude and drifted as far as 300 km SE, ESE, and E. Lava fountains rose up to 500 m above the crater during 27-31 October. Scientists from the Kamchatka Volcanological Station visited the volcano on 28 October and reported that the cinder cone at the summit had grown. They also observed advancing lava on the E flank that extended about 2 km from the summit to 2,700 m elevation, incandescent ejecta 500 m above the crater, and avalanches in the Apakhonchichsky drainage. On 31 October activity intensified, and lava flows were reported moving in the Kretovsky, Kozyrevsky, and Apakhonchichisky drainages on the NW, SW, and SE flanks. At 0930 an ash plume rose to 7 km altitude and at first drifted 169 km SW and then 646 km SE. KVERT reported ash plumes rose to 14 km altitude and extended as far as 1,500 km SSE. The ACC was raised to Red (the highest level on a four-color scale). During 31 October to 1 November ash plumes rose as high as 14 km altitude and drifted as far as 2,255 km ESE.

Activity on 1 November intensified. The lava fountains rose as high as 1 km above the summit (figure 78) and fed the lava flows that were active on the Kretovsky, Kozyrevsky, and Apakhonchichsky drainages on the NW, SW, and SE flanks. Ash plumes rose to 10-14 km altitude and drifted as far as 1,500 km SSE (figure 79). According to the Kamchatka Volcanological Station, observers reported pyroclastic flows descending the flanks. Lahars descended the Studenoy River, blocking the Kozyrevsky-Petropavlovsk federal highway and descended the Krutenkaya River, blocking the road E of Klyuchi. According to news articles the ash plumes caused some flight cancellations and disruptions in the Aleutians, British Columbia (Canada), and along flight paths connecting the Unites States to Japan and South Korea. Ash plumes containing old ash from collapses in the Apakhonchichsky drainage due to phreatic explosions rose to 9.5-9.8 km altitude and drifted 192 km SW at 1400 and to 8.7 km altitude and drifted 192 km SW at 1710 on 1 November.

On 2 November ash plumes rose to 6-14 km altitude; the ash plume that rose to 14 km altitude decreased to 6.5 km altitude and drifted NNE by 2000 and continued to drift more than 3,000 km ESE and E. The ACC was lowered to Orange. On 3 November ash plumes rose to 5-8.2 km altitude and drifted 72-538 km ENE, NNE, and ESE; at 0850 an ash plume rose to 6-6.5 km altitude and drifted more than 3,000 km ESE throughout the day. During 4-6 and 8-10 November resuspended ash plumes associated with collapses of old pyroclastic material from the sides of the Apakhonchichsky drainage due to phreatic explosions rose to 4.5-5.5 km altitude and extended 114-258 km NE, ENE, and E. KVERT reported that the eruption stopped on 5 November and the lava flows had begun to cool. Resuspended ash plumes rose to 5-6 km altitude and drifted 60 km E at 0820 on 13 November and to 5 km and 4.5 km altitude at 1110 and 1430 and drifted 140 km E and 150 km ESE, respectively. On 15 November the ACC was lowered to Green.

Activity was relatively low during most of December. On 27 December Strombolian activity resumed based on a thermal anomaly visible in satellite data. On 30 December an ash plume rose to 6 km altitude and extended 195 km NW. The ACC was raised to Orange. On 31 December video and satellite data showed explosions that generated ash plumes that rose to 5-6.5 km altitude and drifted 50-230 km WNW and NW. Though a thermal anomaly persisted through 1 January 2024, no explosions were detected, so the ACC was lowered to Yellow.

Satellite data. Thermal activity was strong throughout the reporting period due to frequent lava fountaining and lava flows. MODIS thermal anomaly data provided through MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) showed strong activity during the entire reporting period, resulting from lava fountaining and lava flows (figure 80). According to data from MODVOLC thermal alerts, a total of 336 hotspots were detected in June (3), July (30), August (11), September (52), October (217), and November (23). Thermal activity was also visible in infrared satellite images, often showing a strong thermal anomaly at the summit crater and a lava flow affecting primarily the SE and SW flanks (figure 81).

Geologic Background. Klyuchevskoy is the highest and most active volcano on the Kamchatka Peninsula. Since its origin about 6,000 years ago, this symmetrical, basaltic stratovolcano has produced frequent moderate-volume explosive and effusive eruptions without major periods of inactivity. It rises above a saddle NE of Kamen volcano and lies SE of the broad Ushkovsky massif. More than 100 flank eruptions have occurred during approximately the past 3,000 years, with most lateral craters and cones occurring along radial fissures between the unconfined NE-to-SE flanks of the conical volcano between 500 and 3,600 m elevation. Eruptions recorded since the late 17th century have resulted in frequent changes to the morphology of the 700-m-wide summit crater. These eruptions over the past 400 years have originated primarily from the summit crater, but have also included numerous major explosive and effusive eruptions from flank craters.

Information Contacts: Kamchatka Volcanic Eruptions Response Team (KVERT), Far Eastern Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, 9 Piip Blvd., Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, 683006, Russia (URL: http://www.kscnet.ru/ivs/kvert/); Kamchatka Volcanological Station, Kamchatka Branch of Geophysical Survey, (KB GS RAS), Klyuchi, Kamchatka Krai, Russia (URL: http://volkstat.ru/); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Agung (Indonesia) — January 2024  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Agung

Indonesia

8.343°S, 115.508°E; summit elev. 2997 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Three eruptive events reported in April, May, and December 2022

Mount Agung, located on the E end of the island of Bali, Indonesia, rises above the SE rim of the Batur caldera. The summit area extends 1.5 km E-W, with the highest point on the W and a steep-walled 800-m-wide crater on the E. Recorded eruptions date back to the early 19th century. A large and deadly explosive and effusive eruption occurred during 1963-64, which was characterized by voluminous ashfall, pyroclastic flows, and lahars that caused extensive damage and many fatalities. More recent activity was documented during November 2017-June 2019 that consisted of multiple explosions, significant ash plumes, lava flows at the summit crater, and incandescent ejecta. This report covers activity reported during April-May 2022 and December 2022 based on data from the Darwin Volcanic Ash Advisory Center (VAAC).

Activity during 2022 was relatively low and mainly consisted of a few ash plumes during April-May and December. An ash plume on 3 April rising to 3.7 km altitude (700 m above the summit) and drifting N was reported in a Darwin VAAC notice based on a ground report, with ash seen in HIMAWARI-8 visible imagery. Another ash plume was reported at 1120 on 27 May that rose to 5.5 km altitude (2.5 m above the summit); the plume was not visible in satellite or webcam images due to weather clouds. An eruption was reported based on seismic data at 0840 on 13 December, with an estimated plume altitude of 3.7 km; however, no ash was seen using satellite imagery in clear conditions before weather clouds obscured the summit.

Geologic Background. Symmetrical Agung stratovolcano, Bali's highest and most sacred mountain, towers over the eastern end of the island. The volcano, whose name means "Paramount," rises above the SE rim of the Batur caldera, and the northern and southern flanks extend to the coast. The summit area extends 1.5 km E-W, with the high point on the W and a steep-walled 800-m-wide crater on the E. The Pawon cone is located low on the SE flank. Only a few eruptions dating back to the early 19th century have been recorded in historical time. The 1963-64 eruption, one of the largest in the 20th century, produced voluminous ashfall along with devastating pyroclastic flows and lahars that caused extensive damage and many fatalities.

Information Contacts: Darwin Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre (VAAC), Bureau of Meteorology, Northern Territory Regional Office, PO Box 40050, Casuarina, NT 0811, Australia (URL: http://www.bom.gov.au/info/vaac/).

Saunders (United Kingdom) — February 2024  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Saunders

United Kingdom

57.8°S, 26.483°W; summit elev. 843 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Persistent thermal anomalies from the summit crater lava lake during February 2023-January 2024

Saunders is one of eleven islands that comprise the South Sandwich Islands in the South Atlantic. The active Mount Michael volcano has been in almost continuous eruption since November 2014 (BGVN 48:02). Recent activity has resulted in intermittent thermal anomalies and gas-and-steam emissions (BGVN 47:03, 48:02). Visits are infrequent due to its remote location, and cloud cover often prevents satellite observations. Satellite thermal imagery and visual observation of incandescence during a research expedition in 2019 (BGVN 28:02 and 44:08) and a finding confirmed by a National Geographic Society research team that summited Michael in November 2022 reported the presence of a lava lake.

Although nearly constant cloud cover during February 2023 through January 2024 greatly limited satellite observations, thermal anomalies from the lava lake in the summit crater were detected on clear days, especially around 20-23 August 2023. Anomalies similar to previous years (eg. BGVN 48:02) were seen in both MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) data from MODIS instruments and in Sentinel 2 infrared imagery. The only notable sulfur dioxide plume detected near Saunders was on 25 September 2023, with the TROPOMI instrument aboard the Sentinel-5P satellite.

Geologic Background. Saunders Island consists of a large central volcanic edifice intersected by two seamount chains, as shown by bathymetric mapping (Leat et al., 2013). The young Mount Michael stratovolcano dominates the glacier-covered island, while two submarine plateaus, Harpers Bank and Saunders Bank, extend north. The symmetrical Michael has a 500-m-wide summit crater and a remnant of a somma rim to the SE. Tephra layers visible in ice cliffs surrounding the island are evidence of recent eruptions. Ash clouds were reported from the summit crater in 1819, and an effusive eruption was inferred to have occurred from a N-flank fissure around the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. A low ice-free lava platform, Blackstone Plain, is located on the north coast, surrounding a group of former sea stacks. A cluster of cones on the SE flank, the Ashen Hills, appear to have been modified since 1820 (LeMasurier and Thomson, 1990). Analysis of satellite imagery available since 1989 (Gray et al., 2019; MODVOLC) suggests frequent eruptive activity (when weather conditions allow), volcanic clouds, steam plumes, and thermal anomalies indicative of a persistent, or at least frequently active, lava lake in the summit crater. Due to this observational bias, there has been a presumption when defining eruptive periods that activity has been ongoing unless there is no evidence for at least 10 months.

Information Contacts: MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); NASA Global Sulfur Dioxide Monitoring Page, Atmospheric Chemistry and Dynamics Laboratory, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (NASA/GSFC), 8800 Greenbelt Road, Goddard MD 20771, USA (URL: https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/); Copernicus Browser (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser).

Tengger Caldera (Indonesia) — February 2024  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Tengger Caldera

Indonesia

7.942°S, 112.95°E; summit elev. 2329 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Minor ash emission in December 2023; persistent weak thermal anomaly in the Bromo crater

Tengger Caldera, located at the N end of a volcanic massif in Indonesia’s East Java, consists of five overlapping stratovolcanoes. The youngest and only active cone in the 16-km-wide caldera is Bromo, which typically produces gas-and-steam plumes, occasional ash plumes and explosions, and weak thermal signals (BGVN 44:05, 47:01). This report covers activity during January 2022-December 2023, consisting of mostly white gas-and-steam emissions and persistent weak thermal anomalies. Information was provided by the Pusat Vulkanologi dan Mitigasi Bencana Geologi (PVMBG, also known as Indonesian Center for Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation, CVGHM) and satellite imagery. The Alert Level remained at 2 (on a scale of 1-4), and visitors were warned to stay at least 1 km from the crater.

Activity was generally low during the reporting period, similar to that in 2021. According to almost daily images from MAGMA Indonesia (a platform developed by PVMBG), white emissions and plumes rose from 50 to 900 m above the main crater during this period (figure 24). During several days in March and June 2022, white plumes reached heights of 1-1.2 km above the crater.

After an increase in activity at 2114 on 3 February 2023, a PVMBG team that was sent to observe white emissions rising as high as 300 m during 9-12 February and heard rumbling noises. A sulfur dioxide odor was also strong near the crater and measurements indicated that levels were above the healthy (non-hazardous) threshold of 5 parts per million; differential optical absorption spectroscopy (DOAS) measurements indicated an average flux of 190 metric tons per day on 11 February. Incandescence originating from a large fumarole in the NNW part of the crater was visible at night. The team observed that vegetation on the E caldera wall was yellow and withered. The seismic network recorded continuous tremor and deep and shallow volcanic earthquakes.

According to a PVMBG press release, activity increased on 13 December 2023 with white, gray, and brown emissions rising as high as 900 m above Bromo’s crater rim and drifting in multiple directions (figure 25). The report noted that tremor was continuous and was accompanied in December by three volcanic earthquakes. Deformation data indicated inflation in December. There was no observable difference in the persistent thermal anomaly in the crater between 11 and 16 December 2023.

All clear views of the Bromo crater throughout this time, using Sentinel-2 infrared satellite images, showed a weak persistent thermal anomaly; none of the anomalies were strong enough to cause MODVOLC Thermal Alerts. A fire in the SE part of the caldera in early September 2023 resulted in a brief period of strong thermal anomalies.

Geologic Background. The 16-km-wide Tengger caldera is located at the northern end of a volcanic massif extending from Semeru volcano. The massive volcanic complex dates back to about 820,000 years ago and consists of five overlapping stratovolcanoes, each truncated by a caldera. Lava domes, pyroclastic cones, and a maar occupy the flanks of the massif. The Ngadisari caldera at the NE end of the complex formed about 150,000 years ago and is now drained through the Sapikerep valley. The most recent of the calderas is the 9 x 10 km wide Sandsea caldera at the SW end of the complex, which formed incrementally during the late Pleistocene and early Holocene. An overlapping cluster of post-caldera cones was constructed on the floor of the Sandsea caldera within the past several thousand years. The youngest of these is Bromo, one of Java's most active and most frequently visited volcanoes.

Information Contacts: Pusat Vulkanologi dan Mitigasi Bencana Geologi (PVMBG, also known as Indonesian Center for Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation, CVGHM), Jalan Diponegoro 57, Bandung 40122, Indonesia (URL: http://www.vsi.esdm.go.id/); MAGMA Indonesia, Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral (URL: https://magma.esdm.go.id/v1); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/).

Shishaldin (United States) — December 2023  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Shishaldin

United States

54.756°N, 163.97°W; summit elev. 2857 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

New eruption with significant Strombolian explosions, ash plumes, and ashfall

Shishaldin is located on the eastern half of Unimak Island, one of the Aleutian Islands. Frequent explosive activity, primarily consisting of Strombolian ash eruptions from the small summit crater, but sometimes producing lava flows, has been recorded since the 18th century. The previous eruption ended in May 2020 and was characterized by intermittent thermal activity, increased seismicity and surface temperatures, ash plumes, and ash deposits (BGVN 45:06). This report covers a new eruption during July through November 2023, which consisted of significant explosions, ash plumes, ashfall, and lava fountaining. Information comes from daily, weekly, and special reports from the Alaska Volcano Observatory (AVO) and various satellite data. AVO monitors the volcano using local seismic and infrasound sensors, satellite data, web cameras, and remote infrasound and lightning networks.

AVO reported that intermittent tremor and low-frequency earthquakes had gradually become more regular and consistent during 10-13 July. Strongly elevated surface temperatures at the summit were identified in satellite images during 10-13 July. On 11 July AVO raised the Aviation Color Code (ACC) to Yellow (the second color on a four-color scale) and Volcano Alert Level (VAL) to Advisory (the second level on a four-level scale) at 1439. Later in the day on 11 July summit crater incandescence was observed in webcam images. Observations of the summit suggested that lava was likely present at the crater, which prompted AVO to raise the ACC to Orange (the second highest color on a four-color scale) and the VAL to Watch (the second highest level on a four-level scale). The US Coast Guard conducted an overflight on 12 July and confirmed that lava was erupting from the summit. That same day, sulfur dioxide emissions were detected in satellite images.

A significant explosion began at 0109 on 14 July that produced an ash plume that rose to 9-12 km altitude and drifted S over the Pacific Ocean (figure 43). Webcam images and photos taken around 0700 from a ship SW off Unimak Island showed small lahar deposits, which were the result of the interaction of hot pyroclastic material and snow and ice on the flanks. There was also ashfall on the SW and N flanks. A smaller explosion at 0710 generated an ash plume that rose to 4.5 km altitude. Webcam images and pilot reports showed continued low-level ash emissions during the morning, rising to less than 4.6 km altitude; those emissions included a small ash plume near the summit around 1030 resulting from a small explosion.

Seismic tremor amplitude began increasing at around 1700 on 15 July; strongly elevated surface temperatures were also reported. An ash plume rose to 4.6 km altitude and drifted SSE at 2100, based on a satellite image. A continuous ash plume during 2150 through 2330 rose to 5 km altitude and extended 125 km S. At 2357 AVO raised the ACC to Red (the highest color on a four-color scale) and the VAL to Warning (the highest level on a four-level scale), noting that seismicity remained elevated for more than six hours and explosion signals were frequently detected by regional infrasound (pressure sensor) networks. Explosions generated an ash plume that rose to 4.9 km altitude and drifted as far as 500 km SE. Activity throughout the night declined and by 0735 the ACC was lowered to Orange and the VAL to Watch. High-resolution satellite images taken on 16 July showed pyroclastic deposits extending as far as 3 km from the vent; these deposits generated lahars that extended further down the drainages on the flanks. Ash deposits were mainly observed on the SSE flank and extended to the shore of Unimak Island. During 16-17 July lava continued to erupt at the summit, which caused strongly elevated surface temperatures that were visible in satellite imagery.

Lava effusion increased at 0100 on 18 July, as noted in elevated surface temperatures identified in satellite data, increasing seismic tremor, and activity detected on regional infrasound arrays. A significant ash plume at 0700 rose to 7 km altitude and continued until 0830, eventually reaching 9.1 km altitude and drifting SSE (figure 44). As a result, the ACC was raised to Red and the VAL to Warning. By 0930 the main plume detached, but residual low-level ash emissions continued for several hours, remaining below 3 km altitude and drifting S. The eruption gradually declined and by 1208 the ACC was lowered to Orange and the VAL was lowered to Watch. High-resolution satellite images showed ash deposits on the SW flank and pyroclastic deposits on the N, E, and S flanks, extending as far as 3 km from the vent; lahars triggered by the eruption extended farther down the flanks (figure 45). Lava continued to erupt from the summit crater on 19 July.

Elevated surface temperatures were detected in satellite images during 19-25 July, despite occasional weather cloud cover, which was consistent with increased lava effusion. During 22-23 July satellite observations acquired after the eruption from 18 July showed pyroclastic flow and lahar deposits extending as far as 3 km down the N, NW, and NE flanks and as far as 1.5 km down the S and SE flanks. Ash deposits covered the SW and NE flanks. No lava flows were observed outside the crater. On 22 July a sulfur dioxide plume was detected in satellite data midday that had an estimated mass of 10 kt. In a special notice issued at 1653 on 22 July AVO noted that eruptive activity had intensified over the previous six hours, which was characterized by an hours-long steady increase in seismic tremor, intermittent infrasound signals consistent with small explosions, and an increase in surface temperatures that were visible in satellite data. Pilots first reported low-level ash plumes at around 1900. At 2320 an ash plume had risen to 9 km altitude based on additional pilot reports and satellite images. The ACC was increased to Red and the VAL to Warning at 2343. Satellite images indicated growth of a significantly higher ash plume that rose to 11 km altitude continued until 0030 and drifted NE. During the early morning hours of 23 July ash plumes had declined to 4.6 k altitude. Seismic tremor peaked at 0030 on 23 July and began to rapidly decline at 0109; active ash emissions were no longer visible in satellite data by 0130. The ACC was lowered to Orange and the VAL to Watch at 0418; bursts of increased seismicity were recorded throughout the morning, but seismicity generally remained at low levels. Elevated surface temperatures were visible in satellite data until about 0600. On 24 July pilots reported seeing vigorous gas-and-steam plumes rising to about 3 km altitude; the plumes may have contained minor amounts of ash.

During 24-25 July low level seismicity and volcanic tremor were detected at low levels following the previous explosion on 23 July. Strongly elevated surface temperatures were observed at the summit crater in satellite data. Around 2200 on 25 July seismicity began to increase, followed by infrasound signals of explosions after 0200 on 26 July. An ash plume rose to 3 km altitude at 0500 and drifted ENE, along with an associated sulfur dioxide plume that drifted NE and had an estimated mass of 22 kt. Diffuse ash emissions were visible in satellite data and rose to 6.1-7.6 km altitude and extended 125 km from the volcano starting around 1130. These ash events were preceded by about seven hours of seismic tremor, infrasound detections of explosions, and five hours of increased surface temperatures visible in satellite data. Activity began to decline around 1327, which included low-frequency earthquakes and decreased volcanic tremor, and infrasound data no longer detected significant explosions. Surface temperatures remained elevated through the end of the month.

Seismicity, volcanic tremor, and ash emissions remained at low levels during early August. Satellite images on 1 August showed that some slumping had occurred on the E crater wall due to the recent explosive activity. Elevated surface temperatures continued, which was consistent with cooling lava. On 2 August small explosive events were detected, consistent with low-level Strombolian activity. Some episodes of volcanic tremor were reported, which reflected low-level ash emissions. Those ash emissions rose to less than 3 km altitude and drifted as far as 92.6 km N. Pilots that were located N of the volcano observed an ash plume that rose to 2.7 km altitude. Seismicity began to increase in intensity around 0900 on 3 August. Seismicity continued to increase throughout the day and through the night with strongly elevated surface temperatures, which suggested that lava was active at the surface.

An ash cloud that rose to 7.6-7.9 km altitude and drifted 60-75 km NE was visible in a satellite image at 0520 on 4 August. Pilots saw and reported the plume at 0836 (figure 46). By 0900 the plume had risen to 9.1 km altitude and extended over 100 km NE. AVO raised the ACC to Red and the VAL to Warning as a result. Seismic tremor levels peaked at 1400 and then sharply declined at 1500 to slightly elevated levels; the plume was sustained during the period of high tremor and drifted N and NE. The ACC was lowered to Orange and the VAL to Watch at 2055. During 5-14 August seismicity remained low and surface temperatures were elevated based on satellite data due to cooling lava. On 9 August a small lava flow was observed that extended from the crater rim to the upper NE flank. It had advanced to 55 m in length and appeared in satellite imagery on 11 August. Occasional gas-and-steam plumes were noted in webcam images. At 1827 AVO noted that seismic tremor had steadily increased during the afternoon and erupting lava was visible at the summit in satellite images.

Strong explosion signals were detected at 0200 on 15 August. An ash cloud that was visible in satellite data extended 100 km NE and may have risen as high as 11 km altitude around 0240. By 0335 satellite images showed the ash cloud rising to 7.6 km altitude and drifting NE. Significant seismicity and explosions were detected by the local AVO seismic and infrasound networks, and volcanic lightning was detected by the World Wide Lightning Location Network (WWLLN). A sulfur dioxide plume associated with the eruption drifted over the S Bering Sea and parts of Alaska and western Canada. Seismicity was significantly elevated during the eruption but had declined by 1322. A pilot reported that ash emissions continued, rising as high as 4.9 km altitude. Elevated surface temperatures detected in satellite data were caused by hot, eruptive material (pyroclastic debris and lava) that accumulated around the summit. Eruptive activity declined by 16 August and the associated sulfur dioxide plume had mostly dissipated; remnants continued to be identified in satellite images at least through 18 August. Surface temperatures remained elevated based on satellite images, indicating hot material on the upper parts of the volcano. Small explosions were detected in infrasound data on the morning of 19 August and were consistent with pilot reports of small, short-lived ash plumes that rose to about 4.3 km altitude. Low-level explosive activity was reported during 20-24 August, according to seismic and infrasound data, and weather clouds sometimes prevented views. Elevated surface temperatures were observed in satellite images, which indicated continued hot material on the upper parts of the volcano.