Recently Published Bulletin Reports

Agung (Indonesia) Three eruptive events reported in April, May, and December 2022

Tengger Caldera (Indonesia) Minor ash emission in December 2023; persistent weak thermal anomaly in the Bromo crater

Saunders (United Kingdom) Persistent thermal anomalies from the summit crater lava lake during February 2023-January 2024

Shishaldin (United States) New eruption with significant Strombolian explosions, ash plumes, and ashfall

Ioto (Japan) New eruption with discolored water, ejecta, and floating pumice during October-December 2023

Purace (Colombia) Gas-and-ash emission on 16 November 2023

Etna (Italy) Strombolian explosions, lava fountains, and lava flows during July-August 2023

Suwanosejima (Japan) Eruption plumes, crater incandescence, and occasional explosions during July-October 2023

Aira (Japan) Explosions, ash plumes, ash fall, and crater incandescence during July-October 2023

Nishinoshima (Japan) Gray emissions during October 2023

Kilauea (United States) Strong lava fountains, lava flows, and spatter at Halema’uma’u during January-September 2023

Tinakula (Solomon Islands) Continued lava flows and thermal activity during June through November 2023

Agung (Indonesia) — January 2024  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Agung

Indonesia

8.343°S, 115.508°E; summit elev. 2997 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Three eruptive events reported in April, May, and December 2022

Mount Agung, located on the E end of the island of Bali, Indonesia, rises above the SE rim of the Batur caldera. The summit area extends 1.5 km E-W, with the highest point on the W and a steep-walled 800-m-wide crater on the E. Recorded eruptions date back to the early 19th century. A large and deadly explosive and effusive eruption occurred during 1963-64, which was characterized by voluminous ashfall, pyroclastic flows, and lahars that caused extensive damage and many fatalities. More recent activity was documented during November 2017-June 2019 that consisted of multiple explosions, significant ash plumes, lava flows at the summit crater, and incandescent ejecta. This report covers activity reported during April-May 2022 and December 2022 based on data from the Darwin Volcanic Ash Advisory Center (VAAC).

Activity during 2022 was relatively low and mainly consisted of a few ash plumes during April-May and December. An ash plume on 3 April rising to 3.7 km altitude (700 m above the summit) and drifting N was reported in a Darwin VAAC notice based on a ground report, with ash seen in HIMAWARI-8 visible imagery. Another ash plume was reported at 1120 on 27 May that rose to 5.5 km altitude (2.5 m above the summit); the plume was not visible in satellite or webcam images due to weather clouds. An eruption was reported based on seismic data at 0840 on 13 December, with an estimated plume altitude of 3.7 km; however, no ash was seen using satellite imagery in clear conditions before weather clouds obscured the summit.

Geologic Background. Symmetrical Agung stratovolcano, Bali's highest and most sacred mountain, towers over the eastern end of the island. The volcano, whose name means "Paramount," rises above the SE rim of the Batur caldera, and the northern and southern flanks extend to the coast. The summit area extends 1.5 km E-W, with the high point on the W and a steep-walled 800-m-wide crater on the E. The Pawon cone is located low on the SE flank. Only a few eruptions dating back to the early 19th century have been recorded in historical time. The 1963-64 eruption, one of the largest in the 20th century, produced voluminous ashfall along with devastating pyroclastic flows and lahars that caused extensive damage and many fatalities.

Information Contacts: Darwin Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre (VAAC), Bureau of Meteorology, Northern Territory Regional Office, PO Box 40050, Casuarina, NT 0811, Australia (URL: http://www.bom.gov.au/info/vaac/).

Tengger Caldera (Indonesia) — February 2024  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Tengger Caldera

Indonesia

7.942°S, 112.95°E; summit elev. 2329 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Minor ash emission in December 2023; persistent weak thermal anomaly in the Bromo crater

Tengger Caldera, located at the N end of a volcanic massif in Indonesia’s East Java, consists of five overlapping stratovolcanoes. The youngest and only active cone in the 16-km-wide caldera is Bromo, which typically produces gas-and-steam plumes, occasional ash plumes and explosions, and weak thermal signals (BGVN 44:05, 47:01). This report covers activity during January 2022-December 2023, consisting of mostly white gas-and-steam emissions and persistent weak thermal anomalies. Information was provided by the Pusat Vulkanologi dan Mitigasi Bencana Geologi (PVMBG, also known as Indonesian Center for Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation, CVGHM) and satellite imagery. The Alert Level remained at 2 (on a scale of 1-4), and visitors were warned to stay at least 1 km from the crater.

Activity was generally low during the reporting period, similar to that in 2021. According to almost daily images from MAGMA Indonesia (a platform developed by PVMBG), white emissions and plumes rose from 50 to 900 m above the main crater during this period (figure 24). During several days in March and June 2022, white plumes reached heights of 1-1.2 km above the crater.

After an increase in activity at 2114 on 3 February 2023, a PVMBG team that was sent to observe white emissions rising as high as 300 m during 9-12 February and heard rumbling noises. A sulfur dioxide odor was also strong near the crater and measurements indicated that levels were above the healthy (non-hazardous) threshold of 5 parts per million; differential optical absorption spectroscopy (DOAS) measurements indicated an average flux of 190 metric tons per day on 11 February. Incandescence originating from a large fumarole in the NNW part of the crater was visible at night. The team observed that vegetation on the E caldera wall was yellow and withered. The seismic network recorded continuous tremor and deep and shallow volcanic earthquakes.

According to a PVMBG press release, activity increased on 13 December 2023 with white, gray, and brown emissions rising as high as 900 m above Bromo’s crater rim and drifting in multiple directions (figure 25). The report noted that tremor was continuous and was accompanied in December by three volcanic earthquakes. Deformation data indicated inflation in December. There was no observable difference in the persistent thermal anomaly in the crater between 11 and 16 December 2023.

All clear views of the Bromo crater throughout this time, using Sentinel-2 infrared satellite images, showed a weak persistent thermal anomaly; none of the anomalies were strong enough to cause MODVOLC Thermal Alerts. A fire in the SE part of the caldera in early September 2023 resulted in a brief period of strong thermal anomalies.

Geologic Background. The 16-km-wide Tengger caldera is located at the northern end of a volcanic massif extending from Semeru volcano. The massive volcanic complex dates back to about 820,000 years ago and consists of five overlapping stratovolcanoes, each truncated by a caldera. Lava domes, pyroclastic cones, and a maar occupy the flanks of the massif. The Ngadisari caldera at the NE end of the complex formed about 150,000 years ago and is now drained through the Sapikerep valley. The most recent of the calderas is the 9 x 10 km wide Sandsea caldera at the SW end of the complex, which formed incrementally during the late Pleistocene and early Holocene. An overlapping cluster of post-caldera cones was constructed on the floor of the Sandsea caldera within the past several thousand years. The youngest of these is Bromo, one of Java's most active and most frequently visited volcanoes.

Information Contacts: Pusat Vulkanologi dan Mitigasi Bencana Geologi (PVMBG, also known as Indonesian Center for Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation, CVGHM), Jalan Diponegoro 57, Bandung 40122, Indonesia (URL: http://www.vsi.esdm.go.id/); MAGMA Indonesia, Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral (URL: https://magma.esdm.go.id/v1); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/).

Saunders (United Kingdom) — February 2024  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Saunders

United Kingdom

57.8°S, 26.483°W; summit elev. 843 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Persistent thermal anomalies from the summit crater lava lake during February 2023-January 2024

Saunders is one of eleven islands that comprise the South Sandwich Islands in the South Atlantic. The active Mount Michael volcano has been in almost continuous eruption since November 2014 (BGVN 48:02). Recent activity has resulted in intermittent thermal anomalies and gas-and-steam emissions (BGVN 47:03, 48:02). Visits are infrequent due to its remote location, and cloud cover often prevents satellite observations. Satellite thermal imagery and visual observation of incandescence during a research expedition in 2019 (BGVN 28:02 and 44:08) and a finding confirmed by a National Geographic Society research team that summited Michael in November 2022 reported the presence of a lava lake.

Although nearly constant cloud cover during February 2023 through January 2024 greatly limited satellite observations, thermal anomalies from the lava lake in the summit crater were detected on clear days, especially around 20-23 August 2023. Anomalies similar to previous years (eg. BGVN 48:02) were seen in both MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) data from MODIS instruments and in Sentinel 2 infrared imagery. The only notable sulfur dioxide plume detected near Saunders was on 25 September 2023, with the TROPOMI instrument aboard the Sentinel-5P satellite.

Geologic Background. Saunders Island consists of a large central volcanic edifice intersected by two seamount chains, as shown by bathymetric mapping (Leat et al., 2013). The young Mount Michael stratovolcano dominates the glacier-covered island, while two submarine plateaus, Harpers Bank and Saunders Bank, extend north. The symmetrical Michael has a 500-m-wide summit crater and a remnant of a somma rim to the SE. Tephra layers visible in ice cliffs surrounding the island are evidence of recent eruptions. Ash clouds were reported from the summit crater in 1819, and an effusive eruption was inferred to have occurred from a N-flank fissure around the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. A low ice-free lava platform, Blackstone Plain, is located on the north coast, surrounding a group of former sea stacks. A cluster of cones on the SE flank, the Ashen Hills, appear to have been modified since 1820 (LeMasurier and Thomson, 1990). Analysis of satellite imagery available since 1989 (Gray et al., 2019; MODVOLC) suggests frequent eruptive activity (when weather conditions allow), volcanic clouds, steam plumes, and thermal anomalies indicative of a persistent, or at least frequently active, lava lake in the summit crater. Due to this observational bias, there has been a presumption when defining eruptive periods that activity has been ongoing unless there is no evidence for at least 10 months.

Information Contacts: MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); NASA Global Sulfur Dioxide Monitoring Page, Atmospheric Chemistry and Dynamics Laboratory, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (NASA/GSFC), 8800 Greenbelt Road, Goddard MD 20771, USA (URL: https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/); Copernicus Browser (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser).

Shishaldin (United States) — December 2023  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Shishaldin

United States

54.756°N, 163.97°W; summit elev. 2857 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

New eruption with significant Strombolian explosions, ash plumes, and ashfall

Shishaldin is located on the eastern half of Unimak Island, one of the Aleutian Islands. Frequent explosive activity, primarily consisting of Strombolian ash eruptions from the small summit crater, but sometimes producing lava flows, has been recorded since the 18th century. The previous eruption ended in May 2020 and was characterized by intermittent thermal activity, increased seismicity and surface temperatures, ash plumes, and ash deposits (BGVN 45:06). This report covers a new eruption during July through November 2023, which consisted of significant explosions, ash plumes, ashfall, and lava fountaining. Information comes from daily, weekly, and special reports from the Alaska Volcano Observatory (AVO) and various satellite data. AVO monitors the volcano using local seismic and infrasound sensors, satellite data, web cameras, and remote infrasound and lightning networks.

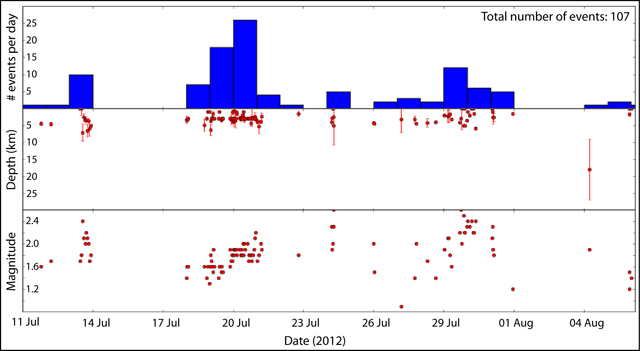

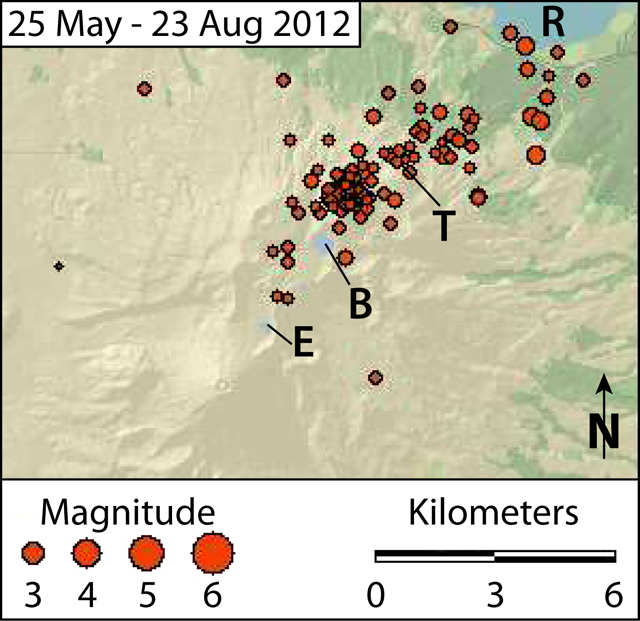

AVO reported that intermittent tremor and low-frequency earthquakes had gradually become more regular and consistent during 10-13 July. Strongly elevated surface temperatures at the summit were identified in satellite images during 10-13 July. On 11 July AVO raised the Aviation Color Code (ACC) to Yellow (the second color on a four-color scale) and Volcano Alert Level (VAL) to Advisory (the second level on a four-level scale) at 1439. Later in the day on 11 July summit crater incandescence was observed in webcam images. Observations of the summit suggested that lava was likely present at the crater, which prompted AVO to raise the ACC to Orange (the second highest color on a four-color scale) and the VAL to Watch (the second highest level on a four-level scale). The US Coast Guard conducted an overflight on 12 July and confirmed that lava was erupting from the summit. That same day, sulfur dioxide emissions were detected in satellite images.

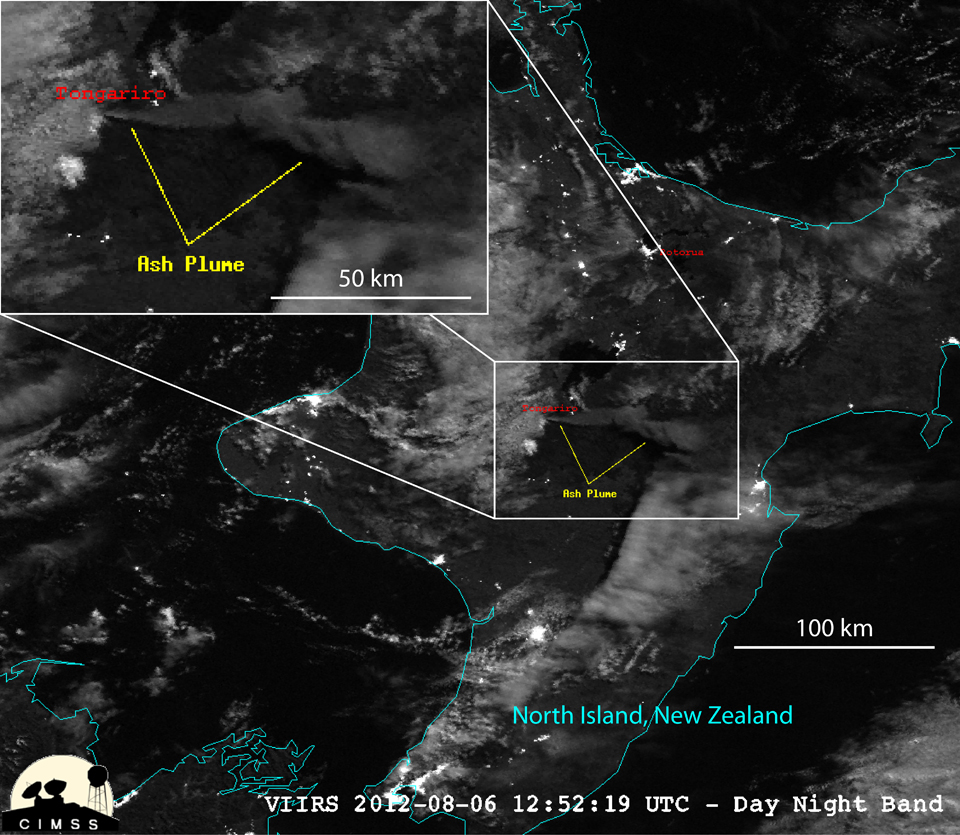

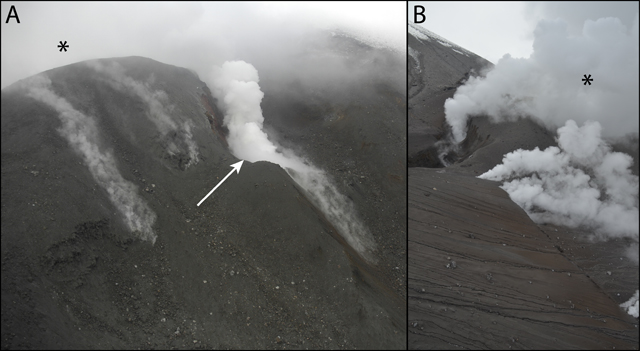

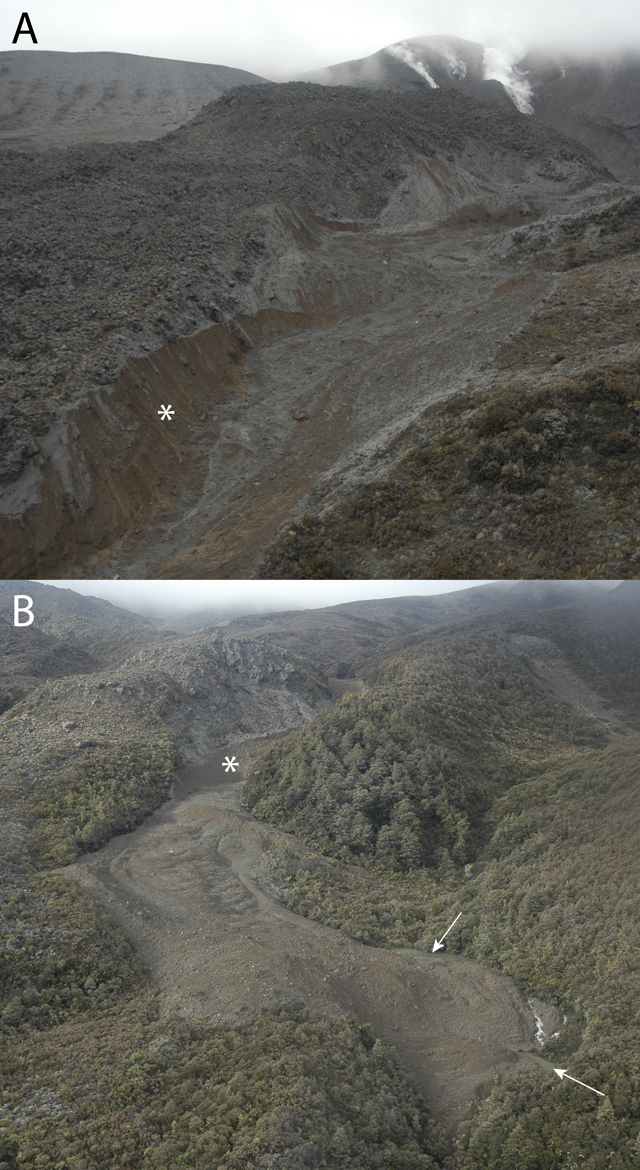

A significant explosion began at 0109 on 14 July that produced an ash plume that rose to 9-12 km altitude and drifted S over the Pacific Ocean (figure 43). Webcam images and photos taken around 0700 from a ship SW off Unimak Island showed small lahar deposits, which were the result of the interaction of hot pyroclastic material and snow and ice on the flanks. There was also ashfall on the SW and N flanks. A smaller explosion at 0710 generated an ash plume that rose to 4.5 km altitude. Webcam images and pilot reports showed continued low-level ash emissions during the morning, rising to less than 4.6 km altitude; those emissions included a small ash plume near the summit around 1030 resulting from a small explosion.

Seismic tremor amplitude began increasing at around 1700 on 15 July; strongly elevated surface temperatures were also reported. An ash plume rose to 4.6 km altitude and drifted SSE at 2100, based on a satellite image. A continuous ash plume during 2150 through 2330 rose to 5 km altitude and extended 125 km S. At 2357 AVO raised the ACC to Red (the highest color on a four-color scale) and the VAL to Warning (the highest level on a four-level scale), noting that seismicity remained elevated for more than six hours and explosion signals were frequently detected by regional infrasound (pressure sensor) networks. Explosions generated an ash plume that rose to 4.9 km altitude and drifted as far as 500 km SE. Activity throughout the night declined and by 0735 the ACC was lowered to Orange and the VAL to Watch. High-resolution satellite images taken on 16 July showed pyroclastic deposits extending as far as 3 km from the vent; these deposits generated lahars that extended further down the drainages on the flanks. Ash deposits were mainly observed on the SSE flank and extended to the shore of Unimak Island. During 16-17 July lava continued to erupt at the summit, which caused strongly elevated surface temperatures that were visible in satellite imagery.

Lava effusion increased at 0100 on 18 July, as noted in elevated surface temperatures identified in satellite data, increasing seismic tremor, and activity detected on regional infrasound arrays. A significant ash plume at 0700 rose to 7 km altitude and continued until 0830, eventually reaching 9.1 km altitude and drifting SSE (figure 44). As a result, the ACC was raised to Red and the VAL to Warning. By 0930 the main plume detached, but residual low-level ash emissions continued for several hours, remaining below 3 km altitude and drifting S. The eruption gradually declined and by 1208 the ACC was lowered to Orange and the VAL was lowered to Watch. High-resolution satellite images showed ash deposits on the SW flank and pyroclastic deposits on the N, E, and S flanks, extending as far as 3 km from the vent; lahars triggered by the eruption extended farther down the flanks (figure 45). Lava continued to erupt from the summit crater on 19 July.

Elevated surface temperatures were detected in satellite images during 19-25 July, despite occasional weather cloud cover, which was consistent with increased lava effusion. During 22-23 July satellite observations acquired after the eruption from 18 July showed pyroclastic flow and lahar deposits extending as far as 3 km down the N, NW, and NE flanks and as far as 1.5 km down the S and SE flanks. Ash deposits covered the SW and NE flanks. No lava flows were observed outside the crater. On 22 July a sulfur dioxide plume was detected in satellite data midday that had an estimated mass of 10 kt. In a special notice issued at 1653 on 22 July AVO noted that eruptive activity had intensified over the previous six hours, which was characterized by an hours-long steady increase in seismic tremor, intermittent infrasound signals consistent with small explosions, and an increase in surface temperatures that were visible in satellite data. Pilots first reported low-level ash plumes at around 1900. At 2320 an ash plume had risen to 9 km altitude based on additional pilot reports and satellite images. The ACC was increased to Red and the VAL to Warning at 2343. Satellite images indicated growth of a significantly higher ash plume that rose to 11 km altitude continued until 0030 and drifted NE. During the early morning hours of 23 July ash plumes had declined to 4.6 k altitude. Seismic tremor peaked at 0030 on 23 July and began to rapidly decline at 0109; active ash emissions were no longer visible in satellite data by 0130. The ACC was lowered to Orange and the VAL to Watch at 0418; bursts of increased seismicity were recorded throughout the morning, but seismicity generally remained at low levels. Elevated surface temperatures were visible in satellite data until about 0600. On 24 July pilots reported seeing vigorous gas-and-steam plumes rising to about 3 km altitude; the plumes may have contained minor amounts of ash.

During 24-25 July low level seismicity and volcanic tremor were detected at low levels following the previous explosion on 23 July. Strongly elevated surface temperatures were observed at the summit crater in satellite data. Around 2200 on 25 July seismicity began to increase, followed by infrasound signals of explosions after 0200 on 26 July. An ash plume rose to 3 km altitude at 0500 and drifted ENE, along with an associated sulfur dioxide plume that drifted NE and had an estimated mass of 22 kt. Diffuse ash emissions were visible in satellite data and rose to 6.1-7.6 km altitude and extended 125 km from the volcano starting around 1130. These ash events were preceded by about seven hours of seismic tremor, infrasound detections of explosions, and five hours of increased surface temperatures visible in satellite data. Activity began to decline around 1327, which included low-frequency earthquakes and decreased volcanic tremor, and infrasound data no longer detected significant explosions. Surface temperatures remained elevated through the end of the month.

Seismicity, volcanic tremor, and ash emissions remained at low levels during early August. Satellite images on 1 August showed that some slumping had occurred on the E crater wall due to the recent explosive activity. Elevated surface temperatures continued, which was consistent with cooling lava. On 2 August small explosive events were detected, consistent with low-level Strombolian activity. Some episodes of volcanic tremor were reported, which reflected low-level ash emissions. Those ash emissions rose to less than 3 km altitude and drifted as far as 92.6 km N. Pilots that were located N of the volcano observed an ash plume that rose to 2.7 km altitude. Seismicity began to increase in intensity around 0900 on 3 August. Seismicity continued to increase throughout the day and through the night with strongly elevated surface temperatures, which suggested that lava was active at the surface.

An ash cloud that rose to 7.6-7.9 km altitude and drifted 60-75 km NE was visible in a satellite image at 0520 on 4 August. Pilots saw and reported the plume at 0836 (figure 46). By 0900 the plume had risen to 9.1 km altitude and extended over 100 km NE. AVO raised the ACC to Red and the VAL to Warning as a result. Seismic tremor levels peaked at 1400 and then sharply declined at 1500 to slightly elevated levels; the plume was sustained during the period of high tremor and drifted N and NE. The ACC was lowered to Orange and the VAL to Watch at 2055. During 5-14 August seismicity remained low and surface temperatures were elevated based on satellite data due to cooling lava. On 9 August a small lava flow was observed that extended from the crater rim to the upper NE flank. It had advanced to 55 m in length and appeared in satellite imagery on 11 August. Occasional gas-and-steam plumes were noted in webcam images. At 1827 AVO noted that seismic tremor had steadily increased during the afternoon and erupting lava was visible at the summit in satellite images.

Strong explosion signals were detected at 0200 on 15 August. An ash cloud that was visible in satellite data extended 100 km NE and may have risen as high as 11 km altitude around 0240. By 0335 satellite images showed the ash cloud rising to 7.6 km altitude and drifting NE. Significant seismicity and explosions were detected by the local AVO seismic and infrasound networks, and volcanic lightning was detected by the World Wide Lightning Location Network (WWLLN). A sulfur dioxide plume associated with the eruption drifted over the S Bering Sea and parts of Alaska and western Canada. Seismicity was significantly elevated during the eruption but had declined by 1322. A pilot reported that ash emissions continued, rising as high as 4.9 km altitude. Elevated surface temperatures detected in satellite data were caused by hot, eruptive material (pyroclastic debris and lava) that accumulated around the summit. Eruptive activity declined by 16 August and the associated sulfur dioxide plume had mostly dissipated; remnants continued to be identified in satellite images at least through 18 August. Surface temperatures remained elevated based on satellite images, indicating hot material on the upper parts of the volcano. Small explosions were detected in infrasound data on the morning of 19 August and were consistent with pilot reports of small, short-lived ash plumes that rose to about 4.3 km altitude. Low-level explosive activity was reported during 20-24 August, according to seismic and infrasound data, and weather clouds sometimes prevented views. Elevated surface temperatures were observed in satellite images, which indicated continued hot material on the upper parts of the volcano.

Seismic tremor began to increase at around 0300 on 25 August and was followed by elevated surface temperatures identified in satellite images, consistent with erupting lava. Small explosions were recorded in infrasound data. The ACC was raised to Red and the VAL to Warning at 1204 after a pilot reported an ash plume that rose to 9.1 km altitude. Seismicity peaked at 1630 and began to rapidly decline at around 1730. Ash plumes rose as high as 10 km altitude and drifted as far as 400 km NE. By 2020 the ash plumes had declined to 6.4 km altitude and continued to drift NE. Ash emissions were visible in satellite data until 0000 on 26 August and seismicity was at low levels. AVO lowered the ACC to Orange and the VAL to Watch at 0030. Minor explosive activity within the summit crater was detected during 26-28 August and strongly elevated surface temperatures were still visible in satellite imagery through the rest of the month. An AVO field crew working on Unimak Island observed a mass flow that descended the upper flanks beginning around 1720 on 27 August. The flow produced a short-lived ash cloud that rose to 4.5 km altitude and rapidly dissipated. The mass flow was likely caused by the collapse of spatter that accumulated on the summit crater rim.

Similar variable explosive activity was reported in September, although weather observations sometimes prevented observations. A moderate resolution satellite image from the afternoon of 1 September showed gas-and-steam emissions filling the summit crater and obscuring views of the vent. In addition, hot deposits from the previous 25-26 August explosive event were visible on the NE flank near the summit, based on a 1 September satellite image. On 2 and 4 September seismic and infrasound data showed signals of small, repetitive explosions. Variable gas-and-steam emissions from the summit were visible but there was no evidence of ash. Possible summit crater incandescence was visible in nighttime webcam images during 3-4 September.

Seismicity began to gradually increase at around 0300 on 5 September and activity escalated at around 0830. A pilot reported an ash plume that rose to 7.6 km altitude at 0842 and continued to rise as high as possibly 9.7 km altitude and drifted SSE based on satellite images (figure 47). The ACC was raised to Red and the VAL to Warning at 0900. In addition to strong tremor and sustained explosions, the eruption produced volcanic lightning that was detected by the WWLLN. Around 1100 seismicity decreased and satellite data confirmed that the altitude of the ash emissions had declined to 7.6 km altitude. By 1200 the lower-altitude portion of the ash plume had drifted 125 km E. Significant ash emissions ended by 1330 based on webcam images. The ACC was lowered to Orange and the VAL to Watch at 1440. Satellite images showed extensive pyroclastic debris flows on most of the flanks that extended 1.2-3.3 km from the crater rim.

During 6-13 September elevated surface temperatures continued to be observed in satellite data, seismicity remained elevated with weak but steady tremor, and small, low-frequency earthquakes and small explosions were reported, except on 12 September. On 6 September a low-level ash plume rose to 1.5-1.8 km altitude and drifted SSE. Occasional small and diffuse gas-and-steam emissions at the summit were visible in webcam images. Around 1800 on 13 September seismic tremor amplitudes began to increase, and small explosions were detected in seismic and infrasound data. Incandescent lava at the summit was seen in a webcam image taken at 0134 on 14 September during a period of elevated tremor. No ash emissions were reported during the period of elevated seismicity. Lava fountaining began around 0200, based on webcam images. Satellite-based radar observations showed that the lava fountaining activity led to the growth of a cone in the summit crater, which refilled most of the crater. By 0730 seismicity significantly declined and remained at low levels.

Seismic tremor began to increase around 0900 on 15 September and rapidly intensified. An explosive eruption began at around 1710, which prompted AVO to raise the ACC to Red and the VAL to Warning. Within about 30 minutes ash plumes drifted E below a weather cloud at 8.2 km altitude. The National Weather Service estimated that an ash-rich plume rose as high as 12.8 km altitude and produced volcanic lightning. The upper part of the ash plume detached from the vent around 1830 and drifted E, and was observed over the Gulf of Alaska. Around the same time, seismicity dramatically decreased. Trace ashfall was reported in the community of False Pass (38 km ENE) between 1800-2030 and also in King Cove and nearby marine waters. Activity declined at around 1830 although seismicity remained elevated, ash emissions, and ashfall continued until 2100. Lightning was again detected beginning around 1930, which suggested that ash emissions continued. Ongoing explosions were detected in infrasound data, at a lower level than during the most energetic phase of this event. Lightning was last detected at 2048. By 2124 the intensity of the eruption had decreased, and ash emissions were likely rising to less than 6.7 km altitude. Seismicity returned to pre-eruption levels. On 16 September the ACC was lowered to Orange and the VAL to Watch at 1244; the sulfur dioxide plume that was emitted from the previous eruption event was still visible over the northern Pacific Ocean. Elevated surface temperatures, gas-and-steam emissions from the vent, and new, small lahars were reported on the upper flanks based on satellite and webcam images. Minor deposits were reported on the flanks which were likely the result of collapse of previously accumulated lava near the summit crater.

Elevated seismicity with tremor, small earthquakes, and elevated surface temperatures were detected during 17-23 September. Minor gas-and-steam emissions were visible in webcam images. On 20 September small volcanic debris flows were reported on the upper flanks. On 21 September a small ash deposit was observed on the upper flanks extending to the NE based on webcam images. Seismic tremor increased significantly during 22-23 September. Regional infrasound sensors suggested that low-level eruptive activity was occurring within the summit crater by around 1800 on 23 September. Even though seismicity was at high levels, strongly elevated surface temperatures indicating lava at the surface were absent and no ash emissions were detected; weather clouds at 0.6-4.6 km altitude obscured views. At 0025 on 24 September AVO noted that seismicity continued at high levels and nearly continuous small infrasound signals began, likely from low-level eruptive activity. Strongly elevated surface temperatures were identified in satellite images by 0900 and persisted throughout the day; the higher temperatures along with infrasound and seismic data were consistent with lava erupting at the summit. Around 1700 similarly elevated surface temperatures were detected from the summit in satellite data, which suggested that more vigorous lava fountaining had started. Starting around 1800 low-level ash emissions rose to altitudes less than 4.6 km altitude and quickly dissipated.

Beginning at midnight on 25 September, a series of seismic signals consistent with volcanic flows were recorded on the N side of the volcano. A change in seismicity and infrasound signals occurred around 0535 and at 0540 a significant ash cloud formed and quickly reached 14 km altitude and drifted E along the Alaska Peninsula. The cloud generated at least 150 lightning strokes with thunder that could be heard by people in False Pass. Seismicity rapidly declined to near background levels around 0600. AVO increased the ACC to Red and the VAL to Warning at 0602. The ash cloud detached from the volcano at around 0700, rose to 11.6 km altitude, and drifted ESE. Trace to minor amounts of ashfall were reported by the communities of False Pass, King Cove, Cold Bay, and Sand Point around 0700. Ash emissions continued at lower altitudes of 6-7.6 km altitude at 0820. Small explosions at the vent area continued to be detected in infrasound data and likely represented low-level eruptive activity near the vent. Due to the significant decrease in seismicity and ash emissions the ACC was lowered to Orange and the VAL to Watch at 1234. Radar data showed significant collapses of the crater that occurred on 25 September. Satellite data also showed significant hot, degassing pyroclastic and lahar deposits on all flanks, including more extensive flows on the ENE and WSW sections below two new collapse scarps. Following the significant activity during 24-25 September, only low-level activity was observed. Seismicity decreased notably near the end of the strong activity on 25 September and continued to decrease through the end of the month, though tremor and small earthquakes were still reported. No explosive activity was detected in infrasound data through 2 October. Gas-and-steam emissions rose to 3.7 km altitude, as reported by pilots and seen in satellite images. Satellite data from 26 September showed that significant collapses had occurred at the summit crater and hot, steaming deposits from pyroclastic flows and lahars were present on all the flanks, particularly to the ENE and WSW. A small ash cloud was visible in webcam images on 27 September, likely from a collapse at the summit cone. High elevated surface temperatures were observed in satellite imagery during 27-28 September, which were likely the result of hot deposits on the flanks erupted on 25 September. Minor steaming at the summit crater and from an area on the upper flanks was visible in webcam images on 28 September.

During October, explosion events continued between periods of low activity. Seismicity significantly increased starting at around 2100 on 2 October; around the same time satellite images showed an increase in surface temperatures consistent with lava fountaining. Small, hot avalanches of rock and lava descended an unspecified flank. In addition, a distinct increase in infrasound, seismicity, and lightning detections was followed by an ash plume that rose to 12.2 km altitude and drifted S and E at 0520 on 3 October, based on satellite images. Nighttime webcam images showed incandescence due to lava fountaining at the summit and pyroclastic flows descending the NE flank. AVO reported that a notable explosive eruption started at 0547 and lasted until 0900 on 3 October, which prompted a rise in the ACC to Red and the VAL to Warning. Subsequent ash plumes rose to 6-7.6 km altitude by 0931. At 1036 the ACC was lowered back to Orange and the VAL to Watch since both seismic and infrasound data quieted substantially and were slightly above background levels. Gas-and-steam emissions were observed at the summit, based on webcam images. Trace amounts of ashfall were observed in Cold Bay. Resuspended ash was present at several kilometers altitude near the volcano. During the afternoon, low-level ash plumes were visible at the flanks, which appeared to be largely generated by rock avalanches off the summit crater following the explosive activity. These ash plumes rose to 3 km altitude and drifted W. Trace amounts of ashfall were reported by observers in Cold Bay and Unalaska and flights to these communities were disrupted by the ash cloud. Satellite images taken after the eruption showed evidence of pyroclastic flows and lahar deposits in drainages 2 km down the SW flank and about 3.2 km down the NE flank, and continued erosion of the crater rim. Small explosion craters at the end of the pyroclastic flows on the NE flank were noted for the first time, which may have resulted from gas-and-steam explosions when hot deposits interact with underlying ice.

During 4 October seismicity, including frequent small earthquakes, remained elevated, but was gradually declining. Ash plumes were produced for over eight hours until around 1400 that rose to below 3.7 km altitude. These ash plumes were primarily generated off the sides of the volcano where hot rock avalanches from the crater rim had entered drainages to the SW and NE. Two explosion craters were observed at the base of the NE deposits about 3.2 km from the crater rim. Webcam images showed the explosion craters were a source of persistent ash emissions; occasional collapse events also generated ash. Seismicity remained elevated with sulfur dioxide emissions that had a daily average of more than 1,000 tons per day, and frequent small earthquakes through the end of the month. Frequent elevated surface temperatures were identified in satellite images and gas-and-steam plumes were observed in webcam images, although weather conditions occasionally prevented clear views of the summit. Emissions were robust during 14-16 October and were likely generated by the interaction of hot material and snow and ice. During the afternoon of 21 October a strong gas-and-steam plume rose to 3-4.6 km altitude and extended 40 km WSW, based on satellite images and reports from pilots. On 31 October the ACC was lowered to Yellow and the VAL was lowered to Advisory.

Activity in November was characterized by elevated seismicity with ongoing seismic tremor and small, low-frequency earthquakes, elevated surface temperatures, and gas-and-steam emissions. There was an increase in seismic and infrasound tremor amplitudes starting at 1940 on 2 November. As a result, the ACC was again raised to Orange and the VAL was increased to Watch, although ash was not identified in satellite data. An ash cloud rose to 6.1 km altitude and drifted W according to satellite data at 2000. By 0831 on 3 November ash emissions were no longer visible in satellite images. On 6 and 9 November air pressure sensors detected signals consistent with small explosions. Small explosions were detected in infrasound data consistent with weak Strombolian activity on 19 and 21 November. Seismicity started to decrease on 21 November. On 25 November gas-and-steam emissions were emitted from the vent as well as from a scarp on the NE side of the volcano near the summit. A gas-and-steam plume extended about 50 km SSE and was observed in satellite and webcam images on 26 November. On 28 November small explosions were observed in seismic and local infrasound data and gas-and-steam emissions were visible from the summit and from the upper NE collapse scarp based on webcam images. Possible small explosions were observed in infrasound data on 30 November. Weakly elevated surface temperatures and a persistent gas-and-steam plume from the summit and collapse scarps on the upper flanks. A passing aircraft reported the gas-and-steam plume rose to 3-3.4 km altitude on 30 November, but no significant ash emissions were detected.

Satellite data. MODIS thermal anomaly data provided through MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) showed a strong pulse of thermal activity beginning in July 2023 that continued through November 2023 (figure 48). This strong activity was due to Strombolian explosions and lava fountaining events at the summit crater. According to data from MODVOLC thermal alerts, a total of 101 hotspots were detected near the summit crater in July (11-14, 16-19, 23-24 and 26), August (4, 25-26, and 29), September (5, 12, and 17), and October (3, 4, and 8). Infrared satellite data showed large lava flows descending primarily the northern and SE flanks during the reporting period (figure 49). Sulfur dioxide plumes often exceeded two Dobson Units (DUs) and drifted in different directions throughout the reporting period, based on satellite data from the TROPOMI instrument on the Sentinel-5P satellite (figure 50).

Geologic Background. The symmetrical glacier-covered Shishaldin in the Aleutian Islands is the westernmost of three large stratovolcanoes in the eastern half of Unimak Island. The Aleuts named the volcano Sisquk, meaning "mountain which points the way when I am lost." Constructed atop an older glacially dissected edifice, it is largely basaltic in composition. Remnants of an older edifice are exposed on the W and NE sides at 1,500-1,800 m elevation. There are over two dozen pyroclastic cones on its NW flank, which is covered by massive aa lava flows. Frequent explosive activity, primarily consisting of Strombolian ash eruptions from the small summit crater, but sometimes producing lava flows, has been recorded since the 18th century. A steam plume often rises from the summit crater.

Information Contacts: Alaska Volcano Observatory (AVO), a cooperative program of a) U.S. Geological Survey, 4200 University Drive, Anchorage, AK 99508-4667 USA (URL: https://avo.alaska.edu/), b) Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, PO Box 757320, Fairbanks, AK 99775-7320, USA, and c) Alaska Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys, 794 University Ave., Suite 200, Fairbanks, AK 99709, USA (URL: http://dggs.alaska.gov/); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); NASA Global Sulfur Dioxide Monitoring Page, Atmospheric Chemistry and Dynamics Laboratory, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (NASA/GSFC), 8800 Greenbelt Road, Goddard, Maryland, USA (URL: https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

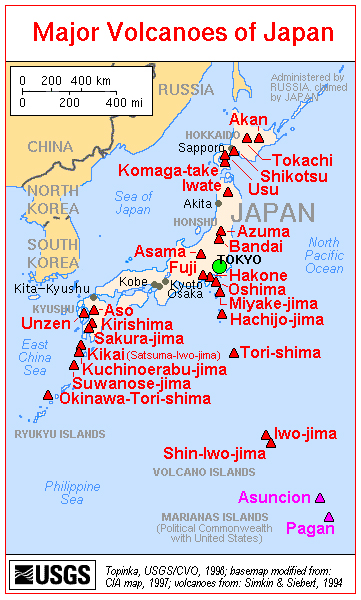

Ioto

Japan

24.751°N, 141.289°E; summit elev. 169 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

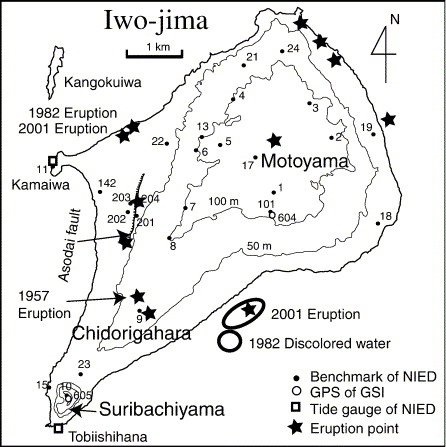

New eruption with discolored water, ejecta, and floating pumice during October-December 2023

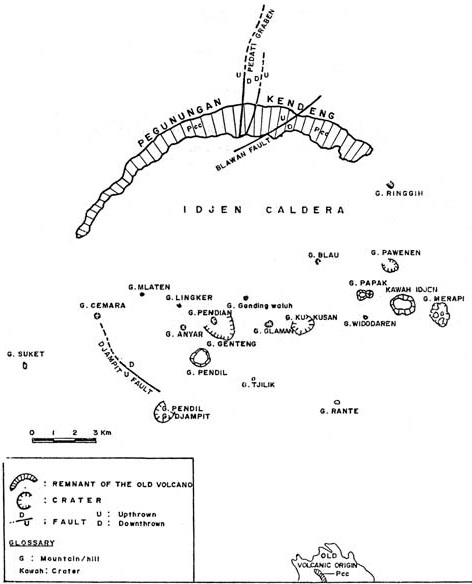

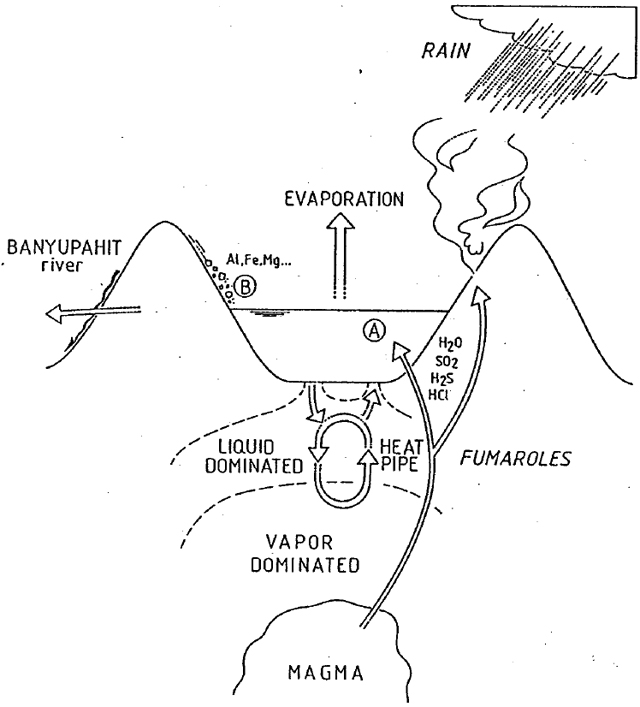

Ioto (Iwo-jima), located about 1,200 km S of Tokyo, lies within a 9-km-wide submarine caldera along the Izu-Bonin-Mariana volcanic arc. Previous eruptions date back to 1889 and have consisted of dominantly phreatic explosions, pumice deposits during 2001, and discolored water. A submarine eruption during July through December 2022 was characterized by discolored water, pumice deposits, and gas emissions (BGVN 48:01). This report covers a new eruption during October through December 2023, which consisted of explosions, black ejecta, discolored water, and floating pumice, based on information from the Japan Meteorological Association (JMA), the Japan Coast Guard (JCG), and satellite data.

JMA reported that an eruption had been occurring offshore of Okinahama on the SE side of the island since 21 October, which was characterized by volcanic tremor, according to the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) Iwo Jima Air Base (figure 22). According to an 18 October satellite image a plume of discolored water at the site of this new eruption extended NE (figure 23). During an overflight conducted on 30 October, a vent was identified about 1 km off the coast of Okinahama. Observers recorded explosions every few minutes that ejected dark material about 20 m above the ocean and as high as 150 m. Ejecta from the vent formed a black-colored island about 100 m in diameter, according to observations conducted from the air by the Earthquake Research Institute of the University of Tokyo in cooperation with the Mainichi newspaper (figure 24). Occasionally, large boulders measuring more than several meters in size were also ejected. Observations from the Advanced Land Observing Satellite Daichi-2 and Sentinel-2 satellite images also confirmed the formation of this island (figure 23). Brown discolored water and floating pumice were present surrounding the island.

The eruption continued during November. During an overflight on 3 November observers photographed the island and noted that material was ejected 169 m high, according to a news source. Explosions gradually became shorter, and, by the 3rd, they occurred every few seconds; dark and incandescent material were ejected about 800 m above the vent. On 4 November eruptions were accompanied by explosive sounds. Floating, brown-colored pumice was present in the water surrounding the island. There was a brief increase in the number of volcanic earthquakes during 8-14 November and 24-25 November. The eruption temporarily paused during 9-11 November and by 12 November eruptions resumed to the W of the island. On 10 November dark brown-to-dark yellow-green discolored water and a small amount of black floating material was observed (figure 25). A small eruption was reported on 18 November off the NE coast of the island, accompanied by white gas-and-steam plumes (figure 23). Another pause was recorded during 17-19 November, which then resumed on 20 November and continued erupting intermittently. According to a field survey conducted by the National Institute for Disaster Prevention Science and Technology on 19 November, a 30-m diameter crater was visible on the NE coast where landslides, hot water, and gray volcanic ash containing clay have occurred and been distributed previously. Erupted blocks about 10 cm in diameter were distributed about 90-120 m from the crater. JCG made observations during an overflight on 23 November and reported a phreatomagmatic eruption. Explosions at the main vent generated dark gas-and-ash plumes that rose to 200 m altitude and ejected large blocks that landed on the island and in the ocean (figure 26). Discolored water also surrounded the island. The size of the new island had grown to 450 m N-S x 200 m E-W by 23 November, according to JCG.

The eruption continued through 11 December, followed by a brief pause in activity, which then resumed on 31 December, according to JMA. Intermittent explosions produced 100-m-high black plumes at intervals of several minutes to 30 minutes during 1-10 December. Overflights were conducted on 4 and 15 December and reported that the water surrounding the new island was discolored to dark brown-to-dark yellow-green (figure 27). No floating material was reported during this time. In comparison to the observations made on 23 November, the new land had extended N and part of it had eroded away. In addition, analysis by the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan using SAR data from Daichi-2 also confirmed that the area of the new island continued to decrease between 4 and 15 December. Ejected material combined with wave erosion transformed the island into a “J” shape, 500-m-long and with the curved part about 200 m offshore of Ioto. The island was covered with brown ash and blocks, and the surrounding water was discolored to greenish-brown and contained an area of floating pumice. JCG reported from an overflight on 4 December that volcanic ash-like material found around the S vent on the NE part of the island was newly deposited since 10 November (figure 28). By 15 December the N part of the “J” shaped island had separated and migrated N, connecting to the Okinahama coast and the curved part of the “J” had eroded into two smaller islands (figure 27).

References. Ukawa, M., Fujita, E., Kobayashi, T., 2002, Recent volcanic activity of Iwo Jima and the 2001 eruption, Monthly Chikyu, Extra No. 39, 157-164.

Geologic Background. Ioto, in the Volcano Islands of Japan, lies within a 9-km-wide submarine caldera. The volcano is also known as Ogasawara-Iojima to distinguish it from several other "Sulfur Island" volcanoes in Japan. The triangular, low-elevation, 8-km-long island narrows toward its SW tip and has produced trachyandesitic and trachytic rocks that are more alkalic than those of other volcanoes in this arc. The island has undergone uplift for at least the past 700 years, accompanying resurgent doming of the caldera; a shoreline landed upon by Captain Cook's surveying crew in 1779 is now 40 m above sea level. The Motoyama plateau on the NE half of the island consists of submarine tuffs overlain by coral deposits and forms the island's high point. Many fumaroles are oriented along a NE-SW zone cutting through Motoyama. Numerous recorded phreatic eruptions, many from vents on the W and NW sides of the island, have accompanied the uplift.

Information Contacts: Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), 1-3-4 Otemachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8122, Japan (URL: http://www.jma.go.jp/jma/indexe.html); Japan Coast Guard (JCG) Volcano Database, Hydrographic and Oceanographic Department, 3-1-1, Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8932, Japan (URL: https://www1.kaiho.mlit.go.jp/GIJUTSUKOKUSAI/kaiikiDB/kaiyo22-2.htm); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/); Asahi, 5-3-2, Tsukiji, Chuo Ward, Tokyo, 104-8011, Japan (URL: https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/15048458).

Purace (Colombia) — December 2023  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Purace

Colombia

2.3095°N, 76.3948°W; summit elev. 4650 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Gas-and-ash emission on 16 November 2023

Puracé, located in Colombia, is a stratovolcano that contains a 500-m-wide summit crater. It is part of the Los Coconucos volcanic chain that is a NW-SE trending group of seven cones and craters. The most recent eruption occurred during March 2022 that was characterized by frequent seismicity and gas-and-steam emissions (BGVN 47:06). This report covers a brief eruption during November 2023 based on monthly reports from the Popayán Observatory, part of the Servicio Geologico Colombiano (SGC).

Activity during November 2022 through November 2023 primarily consisted of seismicity: VT-type events, LP-type events, HB-type events, and TR-type events (table 4). Maximum sulfur dioxide values were measured weekly and ranged from 259-5,854 tons per day (t/d) during November 2022 through April 2023. White gas-and-steam emissions were also occasionally reported.

SGC issued a report on 25 October that noted a significant increase in the number of earthquakes associated with rock fracturing. These earthquakes were located SE of the crater between Puracé and Piocollo at depths of 1-4 km. There were no reported variations in sulfur dioxide values, but SGC noted high carbon dioxide values, compared to those recorded in the first half of 2023.

SGC reported that at 1929 on 16 November the seismic network detected a signal that was possibly associated with a gas-and-ash emission, though it was not confirmed in webcam images due to limited visibility. On 17 November an observer confirmed ash deposits on the N flank. Webcam images showed an increase in degassing both inside the crater and from the NW flank, rising 700 m above the crater.

Table 4. Seismicity at Puracé during November 2022-November 2023. Volcano-tectonic (VT), long-period (LP), hybrid (HB), and tremor (TR) events are reported each month. Courtesy of SGC.

| Month |

Volcano-tectonic |

Long-period |

Hybrid |

Tremor |

| Nov 2022 |

429 |

2,023 |

5 |

831 |

| Dec 2022 |

423 |

1,390 |

9 |

834 |

| Jan 2023 |

719 |

1,622 |

0 |

957 |

| Feb 2023 |

598 |

1,701 |

2 |

1,124 |

| Mar 2023 |

331 |

2,408 |

147 |

607 |

| Apr 2023 |

614 |

4,427 |

33 |

148 |

| May 2023 |

620 |

3,717 |

170 |

109 |

| Jun 2023 |

467 |

3,293 |

86 |

148 |

| Jul 2023 |

1,116 |

5,809 |

183 |

542 |

| Aug 2023 |

692 |

2,927 |

94 |

321 |

| Sep 2023 |

887 |

1,505 |

82 |

848 |

| Oct 2023 |

2,373 |

2,949 |

135 |

692 |

| Nov 2023 |

1,212 |

2,302 |

69 |

293 |

Geologic Background. Puracé is an active andesitic volcano with a 600-m-diameter summit crater at the NW end of the Los Coconucos Volcanic Chain. This volcanic complex includes nine composite and five monogenetic volcanoes, extending from the Puracé crater more than 6 km SE to the summit of Pan de Azúcar stratovolcano. The dacitic massif which the complex is built on extends about 13 km NW-SE and 10 km NE-SW. Frequent small to moderate explosive eruptions reported since 1816 CE have modified the morphology of the summit crater, with the largest eruptions in 1849, 1869, and 1885.

Information Contacts: Servicio Geologico Colombiano (SGC), Diagonal 53 No. 34-53 - Bogotá D.C., Colombia (URL: https://www.sgc.gov.co/volcanes).

Etna

Italy

37.748°N, 14.999°E; summit elev. 3357 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Strombolian explosions, lava fountains, and lava flows during July-August 2023

Etna, located on the Italian island of Sicily, has had documented eruptions dating back to 1500 BCE. Activity typically originates from multiple cones at the summit, where several craters have formed and evolved. The currently active craters are Northeast Crater (NEC), Voragine (VOR), and Bocca Nuova (BN), and the Southeast Crater (SEC); VOR and BN were previously referred to as the “Central Crater”. The original Southeast crater formed in 1978, and a second eruptive site that opened on its SE flank in 2011 was named the New Southeast Crater (NSEC). Another eruptive site between the SEC and NSEC developed during early 2017 and was referred to as the "cono della sella" (saddle cone). The current eruption period began in November 2022 and has been characterized by intermittent Strombolian activity, lava flows, and ash plumes (BGVN 48:08). This report updates activity during July through October 2023, which includes primarily gas-and-steam emissions; during July and August Strombolian explosions, lava fountains, and lava flows were reported, based on weekly and special reports by the Osservatorio Etneo (OE), part of the Catania Branch of Italy's Istituo Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologica (INGV) and satellite data.

Variable fumarolic degassing was reported at all summit craters (BN, VOR, NEC, and SEC) throughout the entire reporting period (table 15). The MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) volcano hotspot detection system based on the analysis of MODIS data showed frequent low-to-moderate power thermal anomalies during the reporting period (figure 399). During mid-August there was a pulse in activity that showed an increase in the power of the anomalies due to Strombolian activity, lava fountains, and lava flows. Infrared satellite imagery captured strong thermal anomalies at the central and southeast summit crater areas (figure 400). Accompanying thermal activity were occasional sulfur dioxide plumes that exceeded 2 Dobson Units (DUs) recorded by the TROPOMI instrument on the Sentinel-5P satellite (figure 401).

Table 15. Summary of activity at the four primary crater areas at the summit of Etna during July-October 2023. Information is from INGV weekly reports.

| Month |

Bocca Nuova (BN) |

Voragine (VOR) |

Northeast Crater (NEC) |

Southeast Crater (SEC) |

| Jul 2023 |

Continuous degassing. |

No observations. |

Weak gas emissions. |

Continuous degassing. Sporadic and weak-to-moderate ash emissions. Strombolian explosions. |

| Aug 2023 |

Continuous degassing. |

No observations. |

No observations. |

Continuous degassing. Occasional ash emissions. Strombolian activity, lava fountaining, and lava flows. |

| Sep 2023 |

Variable degassing. Crater incandescence. |

Weak fumarolic activity. |

Weak fumarolic activity. |

Variable degassing. |

| Oct 2023 |

Continuous degassing. |

Weak fumarolic activity. |

Weak fumarolic activity. |

Continuous degassing. |

Activity during July and August was relatively low and mainly consisted of degassing at the summit craters, particularly at SEC and BN. Cloudy weather prevented clear views of the summit during early July. During the night of 2 July some crater incandescence was visible at SEC. Explosive activity resumed at SEC during 9-10 July, which was characterized by sporadic and weak ash emissions that rapidly dispersed in the summit area (figure 402). INGV reported moderate Strombolian activity began at 2034 on 14 July and was confined to the inside of the crater and fed by a vent located in the E part of SEC. An ash emission was detected at 2037. A new vent opened on 15 July in the SE part of BN and began to produce continuous gas-and-steam emissions. During an inspection carried out on 28 July pulsating degassing, along with audible booms, were reported at two active vents in BN. Vigorous gas-and-steam emissions intermittently generated rings. On rare occasions, fine, reddish ash was emitted from BN1 and resuspended by the gas-and-steam emissions.

Around 2000 on 13 August INGV reported a sudden increase in volcanic tremor amplitude. Significant infrasonic activity coincided with the tremor increase. Incandescent flashes were visible through the cloud cover in webcam images of SEC (figure 403). Strombolian activity at SEC began to gradually intensify starting at 2040 as seismicity continued to increase. The Aviation Color Code (ACC) was raised to Yellow (the second lowest-level on a four-color scale) at 2126 and then to Orange (the second highest-level on a four-color scale) at 2129 due to above-background activity. The activity rapidly transitioned from Strombolian activity to lava fountains around 2333 that rose 300-400 m above the crater (figure 403). Activity was initially focused on the E vent of the crater, but then the vent located above the S flank of the cone also became active. A lava flow from this vent traveled SW into the drainage created on 10 February 2022, overlapping with previous flows from 10 and 21 February 2022 and 21 May 2023, moving between Monte Barbagallo and Monte Frumento Supino (figure 404). The lava flow was 350 m long, oriented NNE-SSW, and descended to an elevation of 2.8 km. Flows covered an area of 300,000 m2 and had an estimated volume of 900,000 m3. The ACC was raised to Red at 2241 based on strong explosive activity and ashfall in Rifugio Sapienza-Piano Vetore at 1.7 km elevation on the S flank. INGV reported that pyroclastic flows accompanied this activity.

Activity peaked between 0240 and 0330 on 14 August, when roughly 5-6 vents erupted lava fountains from the E to SW flank of SEC. The easternmost vents produced lava fountains that ejected material strongly to the E, which caused heavy fallout of incandescent pyroclastic material on the underlying flank, triggering small pyroclastic flows. This event was also accompanied by lightning both in the ash column and in the ash clouds that were generated by the pyroclastic flows. A fracture characterized by a series of collapse craters (pit craters) opened on the upper SW flank of SEC. An ash cloud rose a few kilometers above the crater and drifted S, causing ash and lapilli falls in Rifugio Sapienza and expanding toward Nicolosi, Mascalucia, Catania, and up to Syracuse. Ashfall resulted in operational problems at the Catania airport (50 km S), which lasted from 0238 until 2000. By 0420 the volcanic tremor amplitude values declined to background levels. After 0500 activity sharply decreased, although the ash cloud remained for several hours and drifted S. By late morning, activity had completely stopped. The ACC was lowered to Orange as volcanic ash was confined to the summit area. Sporadic, minor ash emissions continued throughout the day. At 1415 the ACC was lowered to Yellow and then to Green at 1417.

During the night of 14-15 August only occasional flashes were observed, which were more intense during avalanches of material inside the eruptive vents. Small explosions were detected at SEC at 2346 on 14 August and at 0900 on 26 August that each produced ash clouds which rapidly dispersed into the atmosphere (figure 405). According to a webcam image, an explosive event detected at 2344 at SEC generated a modest ash cloud that was rapidly dispersed by winds. The ACC was raised to Yellow at 2355 on 14 August due to increasing unrest and was lowered to Green at 0954 on 15 August.

Activity during September and October was relatively low and mainly characterized by variable degassing from BN and SEC. Intense, continuous, and pulsating degassing was accompanied by roaring sounds and flashes of incandescence at BN both from BN1 and the new pit crater that formed during late July (figure 406). The degassing from the new pit crater sometimes emitted vapor rings. Cloudy weather during 6-8 September prevented observations of the summit craters .

Geologic Background. Mount Etna, towering above Catania on the island of Sicily, has one of the world's longest documented records of volcanism, dating back to 1500 BCE. Historical lava flows of basaltic composition cover much of the surface of this massive volcano, whose edifice is the highest and most voluminous in Italy. The Mongibello stratovolcano, truncated by several small calderas, was constructed during the late Pleistocene and Holocene over an older shield volcano. The most prominent morphological feature of Etna is the Valle del Bove, a 5 x 10 km caldera open to the east. Two styles of eruptive activity typically occur, sometimes simultaneously. Persistent explosive eruptions, sometimes with minor lava emissions, take place from one or more summit craters. Flank vents, typically with higher effusion rates, are less frequently active and originate from fissures that open progressively downward from near the summit (usually accompanied by Strombolian eruptions at the upper end). Cinder cones are commonly constructed over the vents of lower-flank lava flows. Lava flows extend to the foot of the volcano on all sides and have reached the sea over a broad area on the SE flank.

Information Contacts: Sezione di Catania - Osservatorio Etneo, Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV), Sezione di Catania, Piazza Roma 2, 95123 Catania, Italy (URL: http://www.ct.ingv.it/it/); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); NASA Global Sulfur Dioxide Monitoring Page, Atmospheric Chemistry and Dynamics Laboratory, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (NASA/GSFC), 8800 Greenbelt Road, Goddard MD 20771, USA (URL: https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Suwanosejima (Japan) — December 2023  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Suwanosejima

Japan

29.638°N, 129.714°E; summit elev. 796 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Eruption plumes, crater incandescence, and occasional explosions during July-October 2023

Suwanosejima is an 8-km-long island that consists of a stratovolcano and two active summit craters, located in the northern Ryukyu Islands, Japan. Volcanism over the past century has been characterized by Strombolian explosions, ash plumes, and ashfall. The current eruption began in October 2004 and has more recently consisted of frequent eruption plumes, explosions, and incandescent ejecta (BGVN 48:07). This report covers similar activity of ash plumes, explosions, and crater incandescence during July through October 2023 using monthly reports from the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) and satellite data.

Thermal activity during the reporting period was relatively low; only one low-power thermal anomaly was detected during mid-July and one during early August, based on a MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) Log Radiative Power graph of the MODIS thermal anomaly data. On two clear weather days, a thermal anomaly was visible in infrared satellite images (figure 81).

Low-level activity was reported at the Otake crater during July and no explosions were detected. Eruption plumes rose as high as 1.8 km above the crater. On 13 July an ash plume rose 1.7 km above the crater rim, based on a webcam image. During the night of the 28th crater incandescence was visible in a webcam image. An eruptive event reported on 31 July produced an eruption plume that rose 2.1 km above the crater. Seismicity consisted of 11 volcanic earthquakes on the W flank, the number of which had decreased compared to June (28) and 68 volcanic earthquakes near the Otake crater, which had decreased from 722 in the previous month. According to observations conducted by the University of Tokyo Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Toshima Village, and JMA, the amount of sulfur dioxide emissions released during the month was 400-800 tons per day (t/d).

Eruptive activity in the Otake crater continued during August and no explosions were reported. An eruptive event produced a plume that rose 1 km above the crater at 1447 on 12 August. Subsequent eruptive events were recorded at 0911 on 16 August, at 1303 on 20 August, and at 0317 on 21 August, which produced ash plumes that rose 1-1.1 km above the crater and drifted SE, SW, and W. On 22 August an ash plume was captured in a webcam image rising 1.4 km above the crater (figure 82). Multiple eruptive events were detected on 25 August at 0544, 0742, 0824, 1424, and 1704, which generated ash plumes that rose 1.1-1.2 km above the crater and drifted NE, W, and SW. On 28 August a small amount of ashfall was observed as far as 1.5 km from the crater. There were 17 volcanic earthquakes recorded on the W flank of the volcano and 79 recorded at the Otake crater during the month. The amount of sulfur dioxide emissions released during the month was 400-800 t/d.

Activity continued at the Otake crater during September. Occasionally, nighttime crater incandescence was observed in webcam images and ashfall was reported. An eruptive event at 1949 on 4 September produced an ash plume that rose 1 km above the crater and drifted SW. On 9 September several eruption events were detected at 0221, 0301, and 0333, which produced ash plumes that rose 1.1-1.4 km above the crater rim and drifted W; continuous ash emissions during 0404-0740 rose to a maximum height of 2 km above the crater rim (figure 83). More eruptive events were reported at 1437 on 10 September, at 0319 on 11 September, and at 0511 and 1228 on 15 September, which generated ash plumes that rose 1-1.8 km above the crater. During 25, 27, and 30 September, ash plumes rose as high as 1.3 km above the crater rim. JMA reported that large blocks were ejected as far as 300 m from the center of the crater. There were 18 volcanic earthquakes detected beneath the W flank and 82 volcanic earthquakes detected near the Otake crater. The amount of sulfur dioxide released during the month ranged from 600 to 1,600 t/d.

Activity during early-to-mid-October consisted of occasional explosions, a total number of 13, and ash plumes that rose as high as 1.9 km above the Otake crater rim on 29 October (figure 84). These explosions are the first to have occurred since June 2023. Continuous ash emissions were reported during 0510-0555 on 1 October. Explosions were recorded at 0304, 2141, and 2359 on 2 October, at 0112 on 3 October, and at 1326 on 6 October, which produced ash plumes that rose as high as 1 km above the crater rim and drifted SW and W. An explosion was noted at 0428 on 3 October, but emission details were unknown. A total of eight explosions were recorded by the seismic network at 1522 on 14 October, at 0337, 0433, 0555, 1008, and 1539 on 15 October, and at 0454 and 0517 on 16 October. Ash plumes from these explosions rose as high as 900 m above the crater and drifted SE. Eruptive events during 25-27 and 29-30 October generated plumes that rose as high as 1.9 km above the crater and drifted SE, S, and SW. Ash was deposited in Toshima village (3.5 km SSW). Eruptive activity occasionally ejected large volcanic blocks as far as 600 m from the crater. Nighttime crater incandescence was visible in webcams. Intermittent ashfall was reported as far as 1.5 km from the crater. There were 43 volcanic earthquakes detected on the W flank during the month, and 184 volcanic earthquakes detected near the Otake crater. The amount of sulfur dioxide emitted ranged between 400 and 900 t/d.

Geologic Background. The 8-km-long island of Suwanosejima in the northern Ryukyu Islands consists of an andesitic stratovolcano with two active summit craters. The summit is truncated by a large breached crater extending to the sea on the E flank that was formed by edifice collapse. One of Japan's most frequently active volcanoes, it was in a state of intermittent Strombolian activity from Otake, the NE summit crater, between 1949 and 1996, after which periods of inactivity lengthened. The largest recorded eruption took place in 1813-14, when thick scoria deposits covered residential areas, and the SW crater produced two lava flows that reached the western coast. At the end of the eruption the summit of Otake collapsed, forming a large debris avalanche and creating an open collapse scarp extending to the eastern coast. The island remained uninhabited for about 70 years after the 1813-1814 eruption. Lava flows reached the eastern coast of the island in 1884. Only about 50 people live on the island.

Information Contacts: Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), 1-3-4 Otemachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8122, Japan (URL: http://www.jma.go.jp/jma/indexe.html); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Aira

Japan

31.5772°N, 130.6589°E; summit elev. 1117 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Explosions, ash plumes, ash fall, and crater incandescence during July-October 2023

Aira caldera, located in the northern half of Kagoshima Bay, Japan, contains the post-caldera Sakurajima volcano. Eruptions typically originate from the Minamidake crater, and since the 8th century, ash deposits have been recorded in the city of Kagoshima (10 km W), one of Kyushu’s largest cities. The Minamidake summit cone and crater has had persistent activity since 1955; the Showa crater on the E flank has also been intermittently active since 2006. The current eruption period began during March 2017 and has recently been characterized by intermittent explosions, eruption plumes, and ashfall (BGVN 48:07). This report updates activity during July through October 2023 and describes explosive events, ash plumes, nighttime crater incandescence, and ashfall, according to monthly activity reports from the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) and satellite data.

Thermal activity remained at low levels during this reporting period, according to the MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity) system (figure 149). There was a slight increase in the number of anomalies during September through October. Occasional thermal anomalies were visible in infrared satellite images mainly at the Minamidake crater (Vent A is located to the left and Vent B is located to the right) (figure 150).

Table 30. Number of monthly explosive events, days of ashfall, area of ash covered, and sulfur dioxide emissions from Sakurajima’s Minamidake crater at Aira during July-October 2023. Note that smaller ash events are not listed. Ashfall days were measured at Kagoshima Local Meteorological Observatory and ashfall amounts represent material covering all the Kagoshima Prefecture. Data courtesy of JMA monthly reports.

| Month |

Explosive events |

Days of ashfall |

Ashfall amount (g/m2) |

SO2 emissions (tons/day) |

| Jul 2023 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

1,600-3,200 |

| Aug 2023 |

3 |

10 |

7 |

1,800-3,300 |

| Sep 2023 |

3 |

7 |

3 |

1,600-2,300 |

| Oct 2023 |

33 |

8 |

61 |

2,200-4,200 |

JMA reported that during July, there were eight eruptions, three of which were explosion events in the Showa crater. Large blocks were ejected as far as 600 m from the Showa crater. Very small eruptions were occasionally reported at the Minamidake crater. Nighttime incandescence was observed in both the Showa and Minamidake crater. Explosions were reported on 16 July at 2314 and on 17 July at 1224 and at 1232 (figure 151). Resulting eruption plumes rose 700-2,500 m above the crater and drifted N. On 23 July the number of volcanic earthquakes on the SW flank of the volcano increased. A strong Mw 3.1 volcanic earthquake was detected at 1054 on 26 July. The number of earthquakes recorded throughout the month was 545, which markedly increased from 73 in June. No ashfall was observed at the Kagoshima Regional Meteorological Observatory during July. According to a field survey conducted during the month, the daily amount of sulfur dioxide emissions was 1,600-3,200 tons per day (t/d).

There were three eruptions reported at the Minamidake crater during August, each of which were explosive. The explosions occurred on 9 August at 0345, on 13 August at 2205, and on 31 August at 0640, which generated ash plumes that rose 800-2,000 m above the crater and drifted W. There were two eruptions detected at Showa crater; on 4 August at 2150 ejecta traveled 800 m from the Showa crater and associated eruption plumes rose 2.3 km above the crater. The explosion at 2205 on 13 August generated an ash plume that rose 2 km above the crater and was accompanied by large blocks that were ejected 600 m from the Minamidake crater (figure 152). Nighttime crater incandescence was visible in a high-sensitivity surveillance camera at both craters. Seismicity consisted of 163 volcanic earthquakes, 84 of which were detected on the SW flank. According to the Kagoshima Regional Meteorological Observatory there was a total of 7 g/m2 of ashfall over the course of 10 days during the month. According to a field survey, the daily amount of sulfur dioxide emitted was 1,800-3,300 t/d.

During September, four eruptions were reported, three of which were explosion events. These events occurred at 1512 on 9 September, at 0018 on 11 September, and at 2211 on 13 September. Resulting ash plumes generally rose 800-1,100 m above the crater. An explosion produced an ash plume at 2211 on 13 September that rose as high as 1.7 km above the crater. Large volcanic blocks were ejected 600 m from the Minamidake crater. Smaller eruptions were occasionally observed at the Showa crater. Nighttime crater incandescence was visible at the Minamidake crater. Seismicity was characterized by 68 volcanic earthquakes, 28 of which were detected beneath the SW flank. According to the Kagoshima Regional Meteorological Observatory there was a total of 3 g/m2 of ashfall over the course of seven days during the month. A field survey reported that the daily amount of sulfur dioxide emitted was 1,600-2,300 t/d.

Eruptive activity during October consisted of 69 eruptions, 33 of which were described as explosive. These explosions occurred during 4 and 11-21 October and generated ash plumes that rose 500-3,600 m above the crater and drifted S, E, SE, and N. On 19 October at 1648 an explosion generated an ash plume that rose 3.6 km above the crater (figure 153). No eruptions were reported in the Showa crater; white gas-and-steam emissions rose 100 m above the crater from a vent on the N flank. Nighttime incandescence was observed at the Minamidake crater. On 24 October an eruption was reported from 0346 through 0430, which included an ash plume that rose 3.4 km above the crater. Ejected blocks traveled 1.2 km from the Minamidake crater. Following this eruption, small amounts of ashfall were observed from Arimura (4.5 km SE) and a varying amount in Kurokami (4 km E) (figure 154). The number of recorded volcanic earthquakes during the month was 190, of which 14 were located beneath the SW flank. Approximately 61 g/m2 of ashfall was reported over eight days of the month. According to a field survey, the daily amount of sulfur dioxide emitted was 2,200-4,200 t/d.

Geologic Background. The Aira caldera in the northern half of Kagoshima Bay contains the post-caldera Sakurajima volcano, one of Japan's most active. Eruption of the voluminous Ito pyroclastic flow accompanied formation of the 17 x 23 km caldera about 22,000 years ago. The smaller Wakamiko caldera was formed during the early Holocene in the NE corner of the caldera, along with several post-caldera cones. The construction of Sakurajima began about 13,000 years ago on the southern rim and built an island that was joined to the Osumi Peninsula during the major explosive and effusive eruption of 1914. Activity at the Kitadake summit cone ended about 4,850 years ago, after which eruptions took place at Minamidake. Frequent eruptions since the 8th century have deposited ash on the city of Kagoshima, located across Kagoshima Bay only 8 km from the summit. The largest recorded eruption took place during 1471-76.

Information Contacts: Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), 1-3-4 Otemachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8122, Japan (URL: http://www.jma.go.jp/jma/indexe.html); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Copernicus Browser, Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, European Space Agency (URL: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/browser/).

Nishinoshima (Japan) — November 2023  Cite this Report

Cite this Report

Nishinoshima

Japan

27.247°N, 140.874°E; summit elev. 100 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Gray emissions during October 2023

Nishinoshima is a small island in the Ogasawara Arc, about 1,000 km S of Tokyo, Japan. It contains prominent submarine peaks to the S, W, and NE. Recorded eruptions date back to 1973, with the current eruption period beginning in October 2022. Eruption plumes and fumarolic activity characterize recent activity (BGVN 48:10). This report covers the end of the eruption for September through October 2023, based on information from monthly reports of the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) monthly reports, and satellite data.