Costa Rica Volcanoes

A map display is currently under development.

Costa Rica has 10 Holocene volcanoes. Note that as a scientific organization we provide these listings for informational purposes only, with no international legal or policy implications. Volcanoes will be included on this list if they are within the boundaries of a country, on a shared boundary or area, in a remote territory, or within a maritime Exclusive Economic Zone. Bolded volcanoes have erupted within the past 20 years. Suggestions and data updates are always welcome ().

| Volcano Name | Last Eruption | Volcanic Region | Primary Landform |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arenal | 2010 CE | Central America Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Barva | 6050 BCE | Central America Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Irazu | 1977 CE | Central America Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Miravalles | 1946 CE | Central America Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Orosi | Unknown - Evidence Uncertain | Central America Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Platanar | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Central America Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Poas | 2025 CE | Central America Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 2024 CE | Central America Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Tenorio | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Central America Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Turrialba | 2022 CE | Central America Volcanic Arc | Composite |

Chronological listing of known Holocene eruptions (confirmed or uncertain) from volcanoes in Costa Rica. Bolded eruptions indicate continuing activity.

| Volcano Name | Start Date | Stop Date | Certainty | VEI | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poas | 2025 Jan 5 | 2025 May 2 (continuing) | Confirmed | Observations: Reported | |

| Poas | 2023 Dec 1 | 2024 May 5 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 2023 Aug 2 | 2023 Aug 11 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Turrialba | 2022 Jul 17 | 2022 Jul 17 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 2022 Apr 6 | 2022 Apr 6 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Turrialba | 2021 Nov 3 | 2022 Feb 28 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 2021 Jun 28 | 2024 Oct 22 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Turrialba | 2021 Jun 13 | 2021 Jul 23 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Turrialba | 2020 Jun 18 | 2020 Aug 24 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 2020 Jan 30 | 2020 Dec 13 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 2019 Feb 7 | 2019 Sep 30 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 2018 Jul 28 | 2019 Jun 11 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 2018 May 25 | 2018 May 25 | Confirmed | Observations: Reported | |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 2017 May 23 | 2018 Mar 15 ± 3 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 2017 Apr 12 | 2017 Nov 6 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 2016 Jun 5 | 2016 Aug 16 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 2015 Jun 16 | 2016 May 1 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Turrialba | 2015 Mar 8 | 2019 Oct 28 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Turrialba | 2014 Oct 29 | 2014 Dec 8 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 2014 Sep 17 | 2014 Oct 24 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Turrialba | 2013 May 21 | 2013 Jun 4 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 2012 Oct 17 | 2012 Oct 17 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 2012 Feb 19 | 2012 Apr 14 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Turrialba | 2012 Jan 12 | 2012 Jan 18 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 2011 Aug 22 | 2011 Sep 27 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Turrialba | 2011 Jan 14 | 2011 Jan 14 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Turrialba | [2010 Jul 24] | [2010 Aug 15] | Uncertain | ||

| Turrialba | 2010 Jan 5 | 2010 Mar 7 (?) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 2009 Nov 16 ± 15 days | 2014 Oct 13 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 2009 Jan 12 | 2009 Mar 21 (?) | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 2008 Jan 13 | 2008 Jan 13 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 2006 Sep 25 | 2006 Dec 16 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 2006 Mar 24 | 2006 Mar 24 (?) | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1998 Feb 15 | 1998 Sep 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1996 Apr 8 | 1996 Apr 8 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1995 Nov 6 | 1995 Nov 13 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | [1994 Dec 8] | [1994 Dec 8] | Uncertain | ||

| Poas | 1994 Mar 16 (?) ± 15 days | 1994 Oct 16 (?) ± 15 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1992 Oct 16 ± 15 days | 1993 Sep 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 0 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1992 Feb 16 ± 15 days | 1992 Mar 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1991 May 7 | 1992 Sep 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1991 Mar 6 | 1991 Sep 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1987 Jun 16 ± 15 days | 1990 Jun 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1987 Apr 1 | 1987 Apr 1 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1986 Dec 31 | 1986 Dec 31 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1985 Sep 16 ± 15 days | 1986 Apr 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1984 Mar 31 | 1984 Apr 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1983 Feb 6 | 1983 Feb 21 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1981 Mar 16 ± 15 days | 1981 May 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1980 Dec 26 | 1980 Dec 26 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1980 Sep 12 | 1980 Sep 12 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1979 Sep 8 | 1980 Jan 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1978 Sep 22 | 1978 Dec 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1977 Dec 18 | 1978 Jun 15 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1977 May 16 ± 15 days | 1977 Jul 16 (?) ± 15 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | 1977 Mar 3 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1976 Jun 21 | 1976 Nov 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1974 Sep 11 | 1975 Feb 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1972 Feb 9 | 1973 Sep 8 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1970 Aug 14 | 1970 Aug 15 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1970 Jul 16 ± 15 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1969 Sep 20 | 1969 Oct 16 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1969 May 3 | 1969 Jun 3 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1969 Apr 22 | 1969 May 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Arenal | 1968 Jul 29 | 2010 Dec 16 (?) ± 15 days | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1968 Jul 2 ± 182 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1967 Jan 1 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1966 Nov 6 (?) | 1967 Dec 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1964 Dec 25 | 1965 Mar 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1963 May 23 | 1963 Jul 2 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | 1963 Mar 13 | 1965 Feb 13 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1958 Jul 2 ± 182 days | 1961 Jul 3 (?) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1952 Mar 23 | 1957 Dec 25 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1948 | 1951 Jul 2 ± 182 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1946 Nov 4 ± 4 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Miravalles | 1946 Sep 14 | 1946 Sep 14 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1941 | 1946 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | 1939 May 18 | 1940 Feb | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | 1933 Mar 22 (?) | 1933 Jul 25 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1932 | 1934 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | 1930 Oct | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1929 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | 1928 Feb 14 | 1928 May 26 ± 5 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1925 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | 1924 Mar | 1924 Apr | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Arenal | 1922 Oct 5 (?) | 1922 Oct 23 (?) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1922 Apr 11 (on or before) | 1922 Jun 4 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | 1917 Sep 27 | 1921 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | [1917] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Poas | 1916 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Arenal | [1915 Feb 5] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Poas | 1914 Oct 8 | 1915 May 15 (on or after) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1914 May 30 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | [1914 Feb 21] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1912 Jun 14 | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1910 Sep 12 | 1910 Oct 14 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1910 Jan 25 | 1910 Feb | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | [1909] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Rincon de la Vieja | [1902 Jun 22] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Poas | 1898 Dec 29 | 1907 Dec 31 ± 365 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1895 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1888 Jan | 1891 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | 1886 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | 1885 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | [1882] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Poas | 1880 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | [1879] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Irazu | 1875 ± 5 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Barva | [1867 Mar] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Turrialba | 1866 Jan | 1866 May 8 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | 1864 Sep 16 | 1864 Sep 17 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Turrialba | 1864 Aug 17 | 1865 Mar | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Turrialba | [1861] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Poas | 1860 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Turrialba | 1855 May | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1854 | 1863 Aug | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1853 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Turrialba | 1853 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | [1851] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1849 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Unknown |

| Irazu | 1847 May 18 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Turrialba | [1847] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1844 May | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Unknown |

| Irazu | [1844 May] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Irazu | 1842 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | [1838] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Poas | 1834 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Poas | 1828 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | [1826] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Irazu | 1823 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | 1822 May 7 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | [1821 May] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Irazu | 1775 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1765 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Arenal | 1750 ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Poas | 1747 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | 1726 May | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Irazu | 1723 Feb 16 | 1724 Feb (?) | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Turrialba | [1723] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Irazu | 1560 ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Rincon de la Vieja | [1529] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Arenal | 1440 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Arenal | 1400 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Turrialba | 1350 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Poas | 1280 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Irazu | 1110 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Arenal | 1030 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Arenal | 1020 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Arenal | 0750 ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Correlation: Anthropology |

| Arenal | 0700 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Irazu | 0690 ± 40 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Arenal | 0650 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Turrialba | 0640 ± 40 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Arenal | 0550 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 0430 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Irazu | 0430 ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Arenal | 0400 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Correlation: Anthropology |

| Poas | 0210 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Turrialba | 0040 ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Arenal | 0170 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Arenal | 0270 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Arenal | 0380 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Irazu | 0640 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Poas | 0760 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Arenal | 0830 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Turrialba | 0830 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Turrialba | 1120 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Arenal | 1250 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Turrialba | 1420 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Arenal | 1450 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Arenal | 1650 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Arenal | 1770 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Rincon de la Vieja | 1820 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Arenal | 2250 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Arenal | 2800 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Arenal | 3190 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Arenal | 3350 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Arenal | 3900 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Poas | 3950 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Arenal | 4450 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Miravalles | 5050 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Arenal | 5060 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Poas | 5590 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Barva | 6050 BCE ± 2000 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Turrialba | 7260 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Poas | 7620 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Poas | 7920 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

Costa Rica has 12 Pleistocene volcanoes. Note that as a scientific organization we provide these listings for informational purposes only, with no international legal or policy implications. Volcanoes will be included on this list if they are within the boundaries of a country, on a shared boundary or area, in a remote territory, or within a maritime Exclusive Economic Zone. Suggestions and data updates are always welcome ().

| Volcano Name | Volcanic Region | Primary Landform |

|---|---|---|

| Cerro Chopo | Central America Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Isla del Coco | Cocos Ridge Volcanic Province | Shield |

| Lomas de Colorado | Central America Volcanic Arc | Shield |

| Durika | Central America Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Cerro las Mercedes | Central America Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Cerro Negro | Central America Volcanic Arc | Shield |

| Los Perdidos | Central America Volcanic Arc | Caldera |

| Laguna Poco Sol | Central America Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Cerro San Miguel | Central America Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Lomas de Sierpe | Central America Volcanic Arc | Shield |

| Cerro Tilaran | Central America Volcanic Arc | Shield |

| Tortuguero | Central America Volcanic Arc | Minor |

There are 191 photos available for volcanoes in Costa Rica.

Part of the complex summit region of Rincón de la Vieja, the largest volcano in NW Costa Rica, is seen here from the north. Steam rises from the lake-filled Cráter Activo to the left, ENE of the Von Seebach cone (right). Laguna Fria (far-left) is not a crater lake, but a freshwater lake that formed between overlapping cones of the summit complex, which extends east and west beyond this area. Frequent eruptions from Cráter Activo have left surrounding terrain unvegetated.

Part of the complex summit region of Rincón de la Vieja, the largest volcano in NW Costa Rica, is seen here from the north. Steam rises from the lake-filled Cráter Activo to the left, ENE of the Von Seebach cone (right). Laguna Fria (far-left) is not a crater lake, but a freshwater lake that formed between overlapping cones of the summit complex, which extends east and west beyond this area. Frequent eruptions from Cráter Activo have left surrounding terrain unvegetated.Photo by Federico Chavarria Kopper, 1999.

Arenal (left) and Cerro Chato (right) are seen from near El Castillo on the SW side of the volcanic complex. Activity has migrated NW since the earliest eruptions dating back to 38,000 years ago. La Espina and Chatito lava domes are out of view to the right.

Arenal (left) and Cerro Chato (right) are seen from near El Castillo on the SW side of the volcanic complex. Activity has migrated NW since the earliest eruptions dating back to 38,000 years ago. La Espina and Chatito lava domes are out of view to the right. Photo by Jorge Barquero (OVSICORI-UNA).

The Laguna Río Cuarto maar is at the northern end of a chain of vents extending to about 18 km from Poás volcano. The 600 x 750 m wide maar has a maximum depth of 66 m and the crater walls rise 4-20 m above the lake surface. The maar erupted through lahar and alluvial deposits on the coastal plain at an elevation of about 400 m above sea level.

The Laguna Río Cuarto maar is at the northern end of a chain of vents extending to about 18 km from Poás volcano. The 600 x 750 m wide maar has a maximum depth of 66 m and the crater walls rise 4-20 m above the lake surface. The maar erupted through lahar and alluvial deposits on the coastal plain at an elevation of about 400 m above sea level.Photo by Paul Kimberly, 1998 (Smithsonian Institution).

A Strombolian eruption is seen here at Arenal on 15 June 1997. The oldest known Arenal products are about 7,000 years old, and the volcano was active for several thousand years contemporaneously with the older Chato volcano (lower right). A recent eruptive period began with a major explosive event in 1968, and frequent explosive activity and slow lava effusion continued through to 2010.

A Strombolian eruption is seen here at Arenal on 15 June 1997. The oldest known Arenal products are about 7,000 years old, and the volcano was active for several thousand years contemporaneously with the older Chato volcano (lower right). A recent eruptive period began with a major explosive event in 1968, and frequent explosive activity and slow lava effusion continued through to 2010.Photo by Olger Aragón, 1997.

This hummock is part of a massive debris avalanche deposit that formed by collapse of Volcán Cacao. The avalanche traveled across the flat-lying Pacific coastal plain as far as the Central American highway, near where this photo was taken.

This hummock is part of a massive debris avalanche deposit that formed by collapse of Volcán Cacao. The avalanche traveled across the flat-lying Pacific coastal plain as far as the Central American highway, near where this photo was taken.Photo by Lee Siebert, 1998 (Smithsonian Institution).

The Arenal volcanic complex, seen here in 1990 from Lake Arenal to its SW, consists of the Arenal edifice (left) and the older Cerro Chato (right), whose flat summit contains a crater and a crater lake. Activity at the complex has migrated to the NW from the Chatito and La Espina lava domes to the right of Cerro Chato.

The Arenal volcanic complex, seen here in 1990 from Lake Arenal to its SW, consists of the Arenal edifice (left) and the older Cerro Chato (right), whose flat summit contains a crater and a crater lake. Activity at the complex has migrated to the NW from the Chatito and La Espina lava domes to the right of Cerro Chato. Photo by William Melson, 1990 (Smithsonian Institution)

A long-term project by botanists from the Smithsonian Institution studied plant succession on lava flows at Arenal volcano. This field site is located on the west flank. Lake Arenal is visible at the upper right.

A long-term project by botanists from the Smithsonian Institution studied plant succession on lava flows at Arenal volcano. This field site is located on the west flank. Lake Arenal is visible at the upper right.Photo by William Melson, 1988 (Smithsonian Institution).

An ejection of steam and ash rises above the surface of the crater lake of Poás volcano in July 1977. The white ring at the base of the eruption plume is a steam cloud that is traveling along the surface of the lake. Mild phreatic explosions such as this one were typical of the eruption that began in May 1977 and lasted at least until July. The crater walls rise about 250 m above the lake.

An ejection of steam and ash rises above the surface of the crater lake of Poás volcano in July 1977. The white ring at the base of the eruption plume is a steam cloud that is traveling along the surface of the lake. Mild phreatic explosions such as this one were typical of the eruption that began in May 1977 and lasted at least until July. The crater walls rise about 250 m above the lake.Photo by S. Racchini, 1977 (Universidad Nacional Costa Rica, courtesy of Jorge Barquero).

An increase in Strombolian eruptions at Arenal had begun in March 1990. An ash plume rises above the summit on 4 April 1990, seen here from the volcano observatory 2.5 km S. This was part of a long-lived eruption that began in 1968. Explosions produced ash plumes to heights of 1 km above the summit and were accompanied by a lava flow that descended the Río Tabacón on the NW flank down to 700 m altitude. Small pyroclastic flows were also produced.

An increase in Strombolian eruptions at Arenal had begun in March 1990. An ash plume rises above the summit on 4 April 1990, seen here from the volcano observatory 2.5 km S. This was part of a long-lived eruption that began in 1968. Explosions produced ash plumes to heights of 1 km above the summit and were accompanied by a lava flow that descended the Río Tabacón on the NW flank down to 700 m altitude. Small pyroclastic flows were also produced. Photo by William Melson, 1990 (Smithsonian Institution)

Three craters formed from the summit to the lower west flank of Arenal during the initial stages of a long-lived eruption that began on 29 July 1968. The lowermost crater (Crater A) is the near the center of this photo. Crater B is between Crater A and Crater C, which is producing a gas plume near the summit. Crater A was the source of the largest explosions, pyroclastic flows, and ballistic ejecta.

Three craters formed from the summit to the lower west flank of Arenal during the initial stages of a long-lived eruption that began on 29 July 1968. The lowermost crater (Crater A) is the near the center of this photo. Crater B is between Crater A and Crater C, which is producing a gas plume near the summit. Crater A was the source of the largest explosions, pyroclastic flows, and ballistic ejecta. Photo by William Melson, 1968 (Smithsonian Institution).

The low profile of Isla del Coco is seen from the NE, taken from the R/V Searcher of the University of Costa Rica. The 22 km2 rain-drenched island was discovered by the Spanish pilot Juan Cabezas around 1526 CE, and the Costa Rican flag was first planted on the island in 1869. Isla del Coco is the only subaerial portion of the Cocos Ridge, which extends from the Galápagos hot spot to the Mesoamerican trench. Construction of a Pliocene-Pleistocene shield volcano was followed by caldera formation and the emplacement of a trachytic lava dome.

The low profile of Isla del Coco is seen from the NE, taken from the R/V Searcher of the University of Costa Rica. The 22 km2 rain-drenched island was discovered by the Spanish pilot Juan Cabezas around 1526 CE, and the Costa Rican flag was first planted on the island in 1869. Isla del Coco is the only subaerial portion of the Cocos Ridge, which extends from the Galápagos hot spot to the Mesoamerican trench. Construction of a Pliocene-Pleistocene shield volcano was followed by caldera formation and the emplacement of a trachytic lava dome.Photo by Pat Castillo, 1984 (Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California San Diego).

A lake occupies one of the Irazú summit craters (seen here from the southern crater rim in 1996), which has been the source of many recent eruptions. The first well-documented eruption of Irazú occurred in 1723, and frequent explosive eruptions have occurred since. Ashfall from its last major eruption during 1963-65 caused significant disruption to San José and surrounding areas.

A lake occupies one of the Irazú summit craters (seen here from the southern crater rim in 1996), which has been the source of many recent eruptions. The first well-documented eruption of Irazú occurred in 1723, and frequent explosive eruptions have occurred since. Ashfall from its last major eruption during 1963-65 caused significant disruption to San José and surrounding areas.Photo by José Enrique Valverde Sanabria, 1996 (courtesy of Eduardo Malavassi, OVSICORI-UNA).

Steam pours from the surface of the hot, acid lake in the active vent of Poás volcano in this 1983 view from the south. The frequent eruptions from this lake in historical time make Poás one of Costa Rica's most active volcanoes and keep the flanks of the 1-km-wide, 275-m-deep crater vegetation free. Smaller eruptions produce geyser-like activity within the crater lake. Occasional larger eruptions completely eject the crater lake.

Steam pours from the surface of the hot, acid lake in the active vent of Poás volcano in this 1983 view from the south. The frequent eruptions from this lake in historical time make Poás one of Costa Rica's most active volcanoes and keep the flanks of the 1-km-wide, 275-m-deep crater vegetation free. Smaller eruptions produce geyser-like activity within the crater lake. Occasional larger eruptions completely eject the crater lake.Copyrighted photo by Katia and Maurice Krafft, 1983.

The SW side of Volcán Cacao, located at the SE end of the Orosí volcanic massif, is cut by an arcuate depression created during a massive slope failure in which the summit of the volcano was removed. The vertical light-colored stripes on the upper edifice are rockslide scars. The latest eruptive activity at the Orosí complex consisted of post-collapse lava domes and flows from Cerro Cacao.

The SW side of Volcán Cacao, located at the SE end of the Orosí volcanic massif, is cut by an arcuate depression created during a massive slope failure in which the summit of the volcano was removed. The vertical light-colored stripes on the upper edifice are rockslide scars. The latest eruptive activity at the Orosí complex consisted of post-collapse lava domes and flows from Cerro Cacao.Photo by Cindy Stine, 1989 (U.S. Geological Survey).

The upper southern flanks of Irazú contain abundant erosional gullies. The summit is just out of view at the upper right. The northern rim of the currently active summit crater is at the top of this photo, in the center. To the right is the northern rim of the older Diego de la Haya crater.

The upper southern flanks of Irazú contain abundant erosional gullies. The summit is just out of view at the upper right. The northern rim of the currently active summit crater is at the top of this photo, in the center. To the right is the northern rim of the older Diego de la Haya crater. Photo by William Melson, 1986 (Smithsonian Institution).

The summit of Turrialba, the easternmost volcano in the Cordillera Central, is seen here from the SW. It is about 25 km NW of the city of the same name. The summit area is designated as Turrialba National Park, and its northern flanks are part of the extensive Cordillera Volcánica Central forest reserve.

The summit of Turrialba, the easternmost volcano in the Cordillera Central, is seen here from the SW. It is about 25 km NW of the city of the same name. The summit area is designated as Turrialba National Park, and its northern flanks are part of the extensive Cordillera Volcánica Central forest reserve.Photo by Eliecer Duarte (OVSICORI-UNA).

This eroded crater lies near the western margin of Rincón de la Vieja, seen here from the SE. This roughly 1-km-wide crater is about 2 km W of Cráter Activo. On the lower left flank, steep erosional gullies have formed through erosion.

This eroded crater lies near the western margin of Rincón de la Vieja, seen here from the SE. This roughly 1-km-wide crater is about 2 km W of Cráter Activo. On the lower left flank, steep erosional gullies have formed through erosion. Photo by Eliecer Duarte (OVSICORI-UNA).

Small cones of mud and sulfur up to 3 m high formed on the active crater floor during 1989. Eruptive activity from June 1987 to June 1990 included phreatic explosions within the crater lake ejecting mud and sulfur, the formation of temporary small pools of sulfur-rich water, and the emission of sulfur flows up to 30 m long. Acidic gas plumes caused extensive damage to vegetation on the flanks.

Small cones of mud and sulfur up to 3 m high formed on the active crater floor during 1989. Eruptive activity from June 1987 to June 1990 included phreatic explosions within the crater lake ejecting mud and sulfur, the formation of temporary small pools of sulfur-rich water, and the emission of sulfur flows up to 30 m long. Acidic gas plumes caused extensive damage to vegetation on the flanks.Photo by Jorge Barquero, 1989 (Universidad Nacional Costa Rica).

Steam rises from of a small, hot lahar as it travels down the Río Tabacón on the NW flank of Arenal in August 1968, following a powerful explosive eruption that began on 29 July. The lahar damaged the road across the base of the volcano, about 4 km from the summit.

Steam rises from of a small, hot lahar as it travels down the Río Tabacón on the NW flank of Arenal in August 1968, following a powerful explosive eruption that began on 29 July. The lahar damaged the road across the base of the volcano, about 4 km from the summit. Photo by William Melson, 1968 (Smithsonian Institution).

Poás volcano rises above coffee crops on the floor of the central valley of Costa Rica. Poás is the westernmost of three major volcanoes of the Cordillera Central that are easily visible from the capital city of San José and its outskirts. Ash deposits from their eruptions have contributed to fertile agricultural soils in the Central Valley. Poás National Park was established in 1971 and is one of the country's premier natural attractions.

Poás volcano rises above coffee crops on the floor of the central valley of Costa Rica. Poás is the westernmost of three major volcanoes of the Cordillera Central that are easily visible from the capital city of San José and its outskirts. Ash deposits from their eruptions have contributed to fertile agricultural soils in the Central Valley. Poás National Park was established in 1971 and is one of the country's premier natural attractions. Photo by William Melson, 1993 (Smithsonian Institution).

The summit crater complex of Turrialba, Costa Rica's 2nd-highest volcano, is seen here from the SW. Three overlapping summit craters are located at the apex of a large 2 x 4 km summit depression that is widely breached to the NE. The massive stratovolcano had four explosive eruptions during the past 2000 years. These produced pyroclastic flows and surges that devastated areas currently used for agricultural purposes. The most recent eruptions of Turrialba took place during the 19th century.

The summit crater complex of Turrialba, Costa Rica's 2nd-highest volcano, is seen here from the SW. Three overlapping summit craters are located at the apex of a large 2 x 4 km summit depression that is widely breached to the NE. The massive stratovolcano had four explosive eruptions during the past 2000 years. These produced pyroclastic flows and surges that devastated areas currently used for agricultural purposes. The most recent eruptions of Turrialba took place during the 19th century.Copyrighted photo by Katia and Maurice Krafft, 1983.

The acidic crater lake at the summit of Poás is seen here from the overlook on the southern crater rim. The von Frantzius cone in the background formed along the northern rim of the innermost of two large nested calderas at the summit. The crater lake has been the source of frequent phreatic eruptions.

The acidic crater lake at the summit of Poás is seen here from the overlook on the southern crater rim. The von Frantzius cone in the background formed along the northern rim of the innermost of two large nested calderas at the summit. The crater lake has been the source of frequent phreatic eruptions.Photo by Jorge Barquero, 1985 (Universidad Nacional Costa Rica).

The margins of a lava flow descending the WNW flank of Arenal rise above a monument to victims of a powerful explosive eruption in July 1968. Lava flow effusion began on 19 September 1968 and by the time of this December 1968 photo had reached about 2 km from the vent on the lower west flank.

The margins of a lava flow descending the WNW flank of Arenal rise above a monument to victims of a powerful explosive eruption in July 1968. Lava flow effusion began on 19 September 1968 and by the time of this December 1968 photo had reached about 2 km from the vent on the lower west flank.Photo by Dick Berg, 1968 (courtesy of William Melson, Smithsonian Institution).

The infilled, 400 x 500 m wide Diego de la Haya crater in the background was the site of Irazú's first documented eruption in 1723. The eruption began on 16 February 1723, reached peak intensity in February and March, and continued sporadically until 11 December. Incandescent blocks and bombs were ejected, and ash fell on the cities of Cartago, San José, Barva, and Heredia. The active summit crater is to the lower left in this 1998 photo.

The infilled, 400 x 500 m wide Diego de la Haya crater in the background was the site of Irazú's first documented eruption in 1723. The eruption began on 16 February 1723, reached peak intensity in February and March, and continued sporadically until 11 December. Incandescent blocks and bombs were ejected, and ash fell on the cities of Cartago, San José, Barva, and Heredia. The active summit crater is to the lower left in this 1998 photo.Photo by Lee Siebert, 1998 (Smithsonian Institution).

Arenal is seen here from the west in May 1981, with lava flowing from Crater C near the summit. The eruption began in July 1968 with powerful explosions from three craters on the west flank, with the strongest explosions from Crater A. In subsequent years activity migrated towards the summit and took place primarily from Crater C as well as from Crater D (near the former summit).

Arenal is seen here from the west in May 1981, with lava flowing from Crater C near the summit. The eruption began in July 1968 with powerful explosions from three craters on the west flank, with the strongest explosions from Crater A. In subsequent years activity migrated towards the summit and took place primarily from Crater C as well as from Crater D (near the former summit).Photo by William Melson, 1981 (Smithsonian Institution).

The dark lava flow at the lower right, seen here in June 1970, originated from Crater A on the lower western flank of Arenal in September 1968. Gas plumes rise from the B and C craters at the summit.

The dark lava flow at the lower right, seen here in June 1970, originated from Crater A on the lower western flank of Arenal in September 1968. Gas plumes rise from the B and C craters at the summit. Photo by William Melson, 1970 (Smithsonian Institution).

Strombolian explosions during the 1963-65 eruption ejected incandescent lava bombs from the crater, seen here in a time-lapse photo. Similar activity occurred in December 1963 and January 1964.

Strombolian explosions during the 1963-65 eruption ejected incandescent lava bombs from the crater, seen here in a time-lapse photo. Similar activity occurred in December 1963 and January 1964.Photo by M. Esquivel (published in Barquero, 1998).

Poás volcano is visible in this view from the NW with small gas plumes rising from the Botos cone in the center of the complex; the peak to its left is von Frantzius cone. The flank of Cerro Congo is across a saddle from von Frantzius on the far-left horizon. Two large calderas are at the summit, the youngest of which formed about 40,000 years ago.

Poás volcano is visible in this view from the NW with small gas plumes rising from the Botos cone in the center of the complex; the peak to its left is von Frantzius cone. The flank of Cerro Congo is across a saddle from von Frantzius on the far-left horizon. Two large calderas are at the summit, the youngest of which formed about 40,000 years ago.Photo by Dick Berg, 1969 (courtesy of William Melson, Smithsonian Institution).

Miravalles, seen here looking NE from the Guayabo caldera floor, is the youngest feature of the volcanic complex. Multiple edifices have grown in the eastern part of the 15 x 20 km caldera, which formed sometime between 1.5 million and 600,000 years ago.

Miravalles, seen here looking NE from the Guayabo caldera floor, is the youngest feature of the volcanic complex. Multiple edifices have grown in the eastern part of the 15 x 20 km caldera, which formed sometime between 1.5 million and 600,000 years ago.Photo by Guillermo Alvarado, 1985 (Instituto Coastarricense de Electricidad).

This 1992 view from the SW looks towards Arenal with the new active summit crater just right of the pre-1968 summit, the high point to the left. The 1968-onwards eruption constructed the new cone to the west of the crater from the previous major eruption in about 1525 CE. Lava flows from this eruption cover the unvegetated lower western and southern flanks.

This 1992 view from the SW looks towards Arenal with the new active summit crater just right of the pre-1968 summit, the high point to the left. The 1968-onwards eruption constructed the new cone to the west of the crater from the previous major eruption in about 1525 CE. Lava flows from this eruption cover the unvegetated lower western and southern flanks. Photo by William Melson, 1992 (Smithsonian Institution)

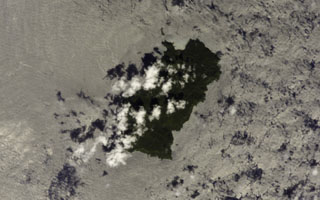

The 22 km2 Isla del Coco (Cocos Islands) is the subaerial portion of the Cocos Ridge, shown in this December 2019 Planet Labs satellite image monthly mosaic (N is at the top). A Pliocene-Pleistocene shield volcano partly forms the roughly 7-km-long (in the NE-SW direction) island. Steep cliffs around the coast expose thick columnar-jointed lava flows, thin lavas, and breccias (possibly debris flows).

The 22 km2 Isla del Coco (Cocos Islands) is the subaerial portion of the Cocos Ridge, shown in this December 2019 Planet Labs satellite image monthly mosaic (N is at the top). A Pliocene-Pleistocene shield volcano partly forms the roughly 7-km-long (in the NE-SW direction) island. Steep cliffs around the coast expose thick columnar-jointed lava flows, thin lavas, and breccias (possibly debris flows).Satellite image courtesy of Planet Labs Inc., 2019 (https://www.planet.com/).

Below the vegetation on the NE Arenal flank is the A2 lava field. These voluminous flows cover the eastern flanks and are considered to have been erupted between about 1700 CE and the start of accurate historical records in Costa Rica in 1800 CE. The vegetation-free flank of the post-1968 cone form the right-hand side of the edifice, and recent lava flows from the 1968-2010 eruption are visible on the lower right-hand flanks with Lake Arenal in the background.

Below the vegetation on the NE Arenal flank is the A2 lava field. These voluminous flows cover the eastern flanks and are considered to have been erupted between about 1700 CE and the start of accurate historical records in Costa Rica in 1800 CE. The vegetation-free flank of the post-1968 cone form the right-hand side of the edifice, and recent lava flows from the 1968-2010 eruption are visible on the lower right-hand flanks with Lake Arenal in the background.Photo by Federico Chavarria Kopper, 1999.

Geologists stand on the margin of a pyroclastic flow deposit from an eruption of Arenal in 1993. In addition to the devastating pyroclastic flows accompanying the start of the eruption in July 1968, more frequent pyroclastic flows occurred in 1975, 1987, 1993, and 1998.

Geologists stand on the margin of a pyroclastic flow deposit from an eruption of Arenal in 1993. In addition to the devastating pyroclastic flows accompanying the start of the eruption in July 1968, more frequent pyroclastic flows occurred in 1975, 1987, 1993, and 1998.Photo by Guillermo Alvarado, 1993 (Instituto Costarricense de Electricidad).

An ash plume rises from the active summit crater of Arenal in this April 1998 view from the south. A small saddle separates the unvegetated post-1968 cone from the pre-1968 cone (right). During April 1998 lava flows traveling down the northern-to-western flanks, and blocks on the NW Crater C wall, broke loose and tiggered small avalanches. This relatively minor activity preceded a larger eruption that produced pyroclastic flows on 5 May.

An ash plume rises from the active summit crater of Arenal in this April 1998 view from the south. A small saddle separates the unvegetated post-1968 cone from the pre-1968 cone (right). During April 1998 lava flows traveling down the northern-to-western flanks, and blocks on the NW Crater C wall, broke loose and tiggered small avalanches. This relatively minor activity preceded a larger eruption that produced pyroclastic flows on 5 May. Photo by Federico Chavarria Kopper, 1998.

This 1968 view of the vegetated summit crater of Arenal is the only known photo of the summit prior to the major eruption that began that year. The previous significant eruption of Arenal (even larger than in 1968) took place in about 1440 CE, and also produced powerful explosions with pyroclastic flows and lava flows.

This 1968 view of the vegetated summit crater of Arenal is the only known photo of the summit prior to the major eruption that began that year. The previous significant eruption of Arenal (even larger than in 1968) took place in about 1440 CE, and also produced powerful explosions with pyroclastic flows and lava flows.Photo by Y. Monestel, 1968 (courtesy of Jorge Barquero, OVSICORI-UNA).

Poás erupted intermittently from June 1987 to June 1990, producing ash plumes such as this one seen on 6 March 1989. Phreatic explosions had resumed from June 1987 until at least October 1988, punctuated by large explosions on 9 April 1988. The crater lake completely disappeared by April 1989, and during May ash plumes reached heights of 1.5-2 km above the crater.

Poás erupted intermittently from June 1987 to June 1990, producing ash plumes such as this one seen on 6 March 1989. Phreatic explosions had resumed from June 1987 until at least October 1988, punctuated by large explosions on 9 April 1988. The crater lake completely disappeared by April 1989, and during May ash plumes reached heights of 1.5-2 km above the crater. Photo by Gerardo Soto, 1989 (Instituto Costarricense de Electricidad, published in Alvarado, 1989).

Frequent eruptions have kept the Irazú summit craters devoid of vegetation. The thick dark-gray ash and scoria units that form the crater walls were emplaced during the 1963-65 eruptions.

Frequent eruptions have kept the Irazú summit craters devoid of vegetation. The thick dark-gray ash and scoria units that form the crater walls were emplaced during the 1963-65 eruptions.Photo by Mike Carr, 1982 (Rutgers University).

Pyroclastic flows descend the flanks of Arenal on 7 July 1987. This was part of the long eruption that began in 1968. The largest pyroclastic flow in this photo taken from the volcano observatory (2.5 km SSW of the summit) is traveling down the SSE flank.

Pyroclastic flows descend the flanks of Arenal on 7 July 1987. This was part of the long eruption that began in 1968. The largest pyroclastic flow in this photo taken from the volcano observatory (2.5 km SSW of the summit) is traveling down the SSE flank.Photo by William Melson, 1987 (Smithsonian Institution)

Turrialba is the SE-most Holocene volcano in Costa Rica, seen here from the upper flank of Irazú to its SW. There are three craters in the upper end of a broad summit scarp that opens towards the NE.

Turrialba is the SE-most Holocene volcano in Costa Rica, seen here from the upper flank of Irazú to its SW. There are three craters in the upper end of a broad summit scarp that opens towards the NE.Photo by William Melson, 1969 (Smithsonian Institution)

A vertical view into the crater lake of Poás volcano in December 1999 shows a gas plume (bottom center) originating from a vent in the south side of the lake. December plume heights ranged between 0.7 and 1 km. The 800-m-wide crater contains an acidic lake.

A vertical view into the crater lake of Poás volcano in December 1999 shows a gas plume (bottom center) originating from a vent in the south side of the lake. December plume heights ranged between 0.7 and 1 km. The 800-m-wide crater contains an acidic lake. Photo by Federico Chavarria Kopper, 2000.

This area was impacted by an 8 December 1994 phreatic explosion is visible from the NW rim of Irazú's summit crater, seen here in 1998. The explosion originated from a geothermal area (lower right) on the upper NW flank and destroyed vegetation down to 2,500 m elevation. The explosion, which produced no juvenile material, created an irregular crater 60-80 m in diameter and sent ashfall to about 30 km distance. Landslides and lahars traveled down the Río Sucio drainage (right center).

This area was impacted by an 8 December 1994 phreatic explosion is visible from the NW rim of Irazú's summit crater, seen here in 1998. The explosion originated from a geothermal area (lower right) on the upper NW flank and destroyed vegetation down to 2,500 m elevation. The explosion, which produced no juvenile material, created an irregular crater 60-80 m in diameter and sent ashfall to about 30 km distance. Landslides and lahars traveled down the Río Sucio drainage (right center).Photo by Lee Siebert, 1998 (Smithsonian Institution).

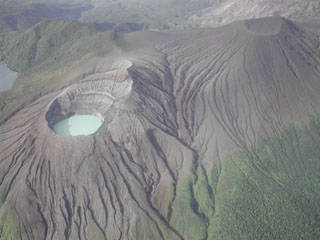

This aerial photo from the north overlooks the Rincón de la Vieja summit cone complex in NW Costa Rica. A gas plume rises from the acidic Cráter Activo lake, and erosional gullies have formed across the flanks. The darker Laguna Fria beyond the Cráter Activo is a non-volcanic lake formed between the vegetated Rincón de la Vieja crater (far-left) and the ridge extending to Santa María to the upper left of the photo.

This aerial photo from the north overlooks the Rincón de la Vieja summit cone complex in NW Costa Rica. A gas plume rises from the acidic Cráter Activo lake, and erosional gullies have formed across the flanks. The darker Laguna Fria beyond the Cráter Activo is a non-volcanic lake formed between the vegetated Rincón de la Vieja crater (far-left) and the ridge extending to Santa María to the upper left of the photo. Photo by Federico Chavarria Kopper, 1996.

Ash plumes rise above vents in the Poás summit crater on 4 May 1990, near the end of an eruptive period that began in June 1987. At the time of this photo the crater lake had shrunk substantially to only several centimeters deep that fluctuated slightly with changes in rainfall recharge. Lake temperatures were over 72°C (measured by infrared thermometer), and small hot springs around the lake had temperatures of 85°C. Minor explosive eruptions continued into the following month.

Ash plumes rise above vents in the Poás summit crater on 4 May 1990, near the end of an eruptive period that began in June 1987. At the time of this photo the crater lake had shrunk substantially to only several centimeters deep that fluctuated slightly with changes in rainfall recharge. Lake temperatures were over 72°C (measured by infrared thermometer), and small hot springs around the lake had temperatures of 85°C. Minor explosive eruptions continued into the following month. Photo by Jorge Barquero, 1990 (Universidad Nacional Costa Rica).

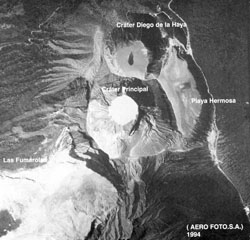

The Irazú main crater is about 700 m wide and 200 m deep. It is seen here in 1998 from the summit, with ash-covered Playa Hermosa (a largely buried older crater) to the lower right, and the edge of Diego de la Haya crater to the upper right.

The Irazú main crater is about 700 m wide and 200 m deep. It is seen here in 1998 from the summit, with ash-covered Playa Hermosa (a largely buried older crater) to the lower right, and the edge of Diego de la Haya crater to the upper right. Photo by Lee Siebert, 1998 (Smithsonian Institution).

Botos is the southernmost of the three cones forming the summit of Poás volcano. Following cessation of eruptions at Botos, activity shifted NW to the now-active summit crater. The floor of the 1-km-wide crater is now covered by Laguna del Agua Fría.

Botos is the southernmost of the three cones forming the summit of Poás volcano. Following cessation of eruptions at Botos, activity shifted NW to the now-active summit crater. The floor of the 1-km-wide crater is now covered by Laguna del Agua Fría.Photo by Ichio Moriya (Kanazawa University).

The Poás crater lake is seen here on 4 October 1987 during an intermittent eruption lasting from June 1987 to June 1990. Sporadic small phreatic explosions had started in June 1987 and continued until at least October 1988. The crater lake disappeared by April 1989, and in the following month ash plumes reached heights of 1.5-2 km above the crater.

The Poás crater lake is seen here on 4 October 1987 during an intermittent eruption lasting from June 1987 to June 1990. Sporadic small phreatic explosions had started in June 1987 and continued until at least October 1988. The crater lake disappeared by April 1989, and in the following month ash plumes reached heights of 1.5-2 km above the crater. Photo by José Enrique Valverde Sanabria, 1987 (courtesy of Eduardo Malavassi, OVSICORA-UNA).

The initial explosions of the 1968 Arenal eruption took place at three craters located from the summit down the west flank. Crater A is visible in the sunlight at the center of the photo; this was the source of the devastating explosions on 29 July. A gas plume rises from Crater B, obscuring Crater C behind it. Lava effusion from Crater C began in September and continued for many years.

The initial explosions of the 1968 Arenal eruption took place at three craters located from the summit down the west flank. Crater A is visible in the sunlight at the center of the photo; this was the source of the devastating explosions on 29 July. A gas plume rises from Crater B, obscuring Crater C behind it. Lava effusion from Crater C began in September and continued for many years. Photo by William Melson, 1968 (Smithsonian Institution).

The rim of one of the three craters filling the large summit depression of Turrialba volcano is seen in the foreground. A scarp wall is visible in the background. Eruptions during the 18th and 19th centuries have originated from the three small craters.

The rim of one of the three craters filling the large summit depression of Turrialba volcano is seen in the foreground. A scarp wall is visible in the background. Eruptions during the 18th and 19th centuries have originated from the three small craters.Photo by Gerardo Soto (published in Alvarado, 1989).

Minor phreatic eruptions ejecting material to heights of several meters were reported in March 1994. Two more phreatic eruptions were reported at the end of April, by which time the crater lake was nearly gone. Intense gas emission in the ensuing months caused health problems and severe economic losses in agricultural areas. Eruptions producing ash plumes that took place on 3 June and 9 July-5 August formed a small new crater. The crater lake (seen here 2 September 1994) returned, and minor phreatic eruptions occurred in October.

Minor phreatic eruptions ejecting material to heights of several meters were reported in March 1994. Two more phreatic eruptions were reported at the end of April, by which time the crater lake was nearly gone. Intense gas emission in the ensuing months caused health problems and severe economic losses in agricultural areas. Eruptions producing ash plumes that took place on 3 June and 9 July-5 August formed a small new crater. The crater lake (seen here 2 September 1994) returned, and minor phreatic eruptions occurred in October. Photo by José Enrique Valverde Sanabria, 1994 (courtesy of Eduardo Malavassi, OVSICORA-UNA).

A lava flow issuing from Crater A is seen in April 1969. This crater was the source of the largest explosions at the onset of the eruption in July 1968. The distal end of the lava flow can be seen across the center of the photo. This flow initially traveled down the Río Tabacón on the NW flank, but later sent lobes over a broad area extending to the SW.

A lava flow issuing from Crater A is seen in April 1969. This crater was the source of the largest explosions at the onset of the eruption in July 1968. The distal end of the lava flow can be seen across the center of the photo. This flow initially traveled down the Río Tabacón on the NW flank, but later sent lobes over a broad area extending to the SW.Photo by William Melson, 1969 (Smithsonian Institution).

A steam plume rises from Cráter Activo of Rincón de la Vieja, seen here from the south with an acidic crater lake filling the innermost of two nested craters. Frequent eruptions and acid rain have kept the flanks of the cone unvegetated. Remobilization of fresh deposits has produced lahars down the Quebrada Azufrosa to the upper right.

A steam plume rises from Cráter Activo of Rincón de la Vieja, seen here from the south with an acidic crater lake filling the innermost of two nested craters. Frequent eruptions and acid rain have kept the flanks of the cone unvegetated. Remobilization of fresh deposits has produced lahars down the Quebrada Azufrosa to the upper right.Photo by Federico Chavarria Kopper, 1999.

Electrical power from the Miravalles geothermal plant is distributed from the control room of Project CORTEZ. The Miravalles I and II wells produce 60 and 55 MW of power, respectively, through reinjection. The vapor-phase Miravalles III well is expected to produce 27.5 MW. The depths of the geothermal wells vary from 959 to 3022 m.

Electrical power from the Miravalles geothermal plant is distributed from the control room of Project CORTEZ. The Miravalles I and II wells produce 60 and 55 MW of power, respectively, through reinjection. The vapor-phase Miravalles III well is expected to produce 27.5 MW. The depths of the geothermal wells vary from 959 to 3022 m.Photo by Guillermo Alvarado (Instituto Costarricense de Electricidad).

Strombolian eruptions from Arenal volcano are reflected in Lake Arenal in December 1992 during an eruption that began on 29 July 1968. The eruption produced major explosions and pyroclastic flows from three new vents on the west flank, destroying two towns and killing 78 people. The eruption continued through to 2010 and lava flows formed an extensive lava field on the west flank, accompanied by intermittent explosive activity.

Strombolian eruptions from Arenal volcano are reflected in Lake Arenal in December 1992 during an eruption that began on 29 July 1968. The eruption produced major explosions and pyroclastic flows from three new vents on the west flank, destroying two towns and killing 78 people. The eruption continued through to 2010 and lava flows formed an extensive lava field on the west flank, accompanied by intermittent explosive activity.Photo by Olger Aragón, 1992.

An aerial perspective of the Arenal summit area shows the older cone in the foreground and the active degassing cone in the background. Notice the newly formed small darker-colored cone on the right (north) in this 10 March 1999 photograph.

An aerial perspective of the Arenal summit area shows the older cone in the foreground and the active degassing cone in the background. Notice the newly formed small darker-colored cone on the right (north) in this 10 March 1999 photograph. Photo by Federico Chavarria Kopper, 1999 (courtesy of Eduardo Malavassi, OVSICORI-UNA).

The forested Tenorio volcanic complex contains a group of volcanic cones at the SE end of the Guanacaste Range. Geothermal activity is present on the NE flank.

The forested Tenorio volcanic complex contains a group of volcanic cones at the SE end of the Guanacaste Range. Geothermal activity is present on the NE flank.Photo by Cindy Stine, 1989 (U.S. Geological Survey).

Poás is a broad volcano with a summit area containing three craters and is one of the most active volcanoes of Costa Rica. This photo from the east shows a plume rising from the active summit crater, which has been the site of frequent phreatic and phreatomagmatic eruptions since 1828, and the lake filled Botos crater to the left.

Poás is a broad volcano with a summit area containing three craters and is one of the most active volcanoes of Costa Rica. This photo from the east shows a plume rising from the active summit crater, which has been the site of frequent phreatic and phreatomagmatic eruptions since 1828, and the lake filled Botos crater to the left. Photo by Mike Carr (Rutgers University).

A plume containing ash and mud erupts through the Poás crater lake in July 1977 when phreatic explosions were produced at 25-minute intervals. This activity had begun in May 1977.

A plume containing ash and mud erupts through the Poás crater lake in July 1977 when phreatic explosions were produced at 25-minute intervals. This activity had begun in May 1977. Photo by S. Racchini, 1977 (Universidad Nacional Costa Rica, courtesy of Jorge Barquero).

Intermittent explosive activity during the 1963-65 Irazú eruption cumulatively produced extensive ashfall that caused significant economic damage to San Jose and other populated areas of the Central Valley of Costa Rica. During the first weeks of January 1964 heavy ashfall was deposited as far away as Tamarindo beach on the Pacific coast and Lake Nicaragua, 180 km NE of the volcano.

Intermittent explosive activity during the 1963-65 Irazú eruption cumulatively produced extensive ashfall that caused significant economic damage to San Jose and other populated areas of the Central Valley of Costa Rica. During the first weeks of January 1964 heavy ashfall was deposited as far away as Tamarindo beach on the Pacific coast and Lake Nicaragua, 180 km NE of the volcano.Photo by W. Schaer (published in Barquero, 1998).

People at the Arenal Volcano Observatory watch a S-flank pyroclastic flow on 23 January 1991. Pyroclastic flows occasionally descended the flanks throughout the long-lived eruption that began in 1968.

People at the Arenal Volcano Observatory watch a S-flank pyroclastic flow on 23 January 1991. Pyroclastic flows occasionally descended the flanks throughout the long-lived eruption that began in 1968.Photo by McDiarmid, 1991 (courtesy of William Melson, Smithsonian Institution).

Laguna de Fria (center) is seen here from the west, along a ridge near Cráter Activo. It formed when meteoric water accumulated in a depression between overlapping cones of the Rincón de la Vieja complex. Rincón de la Vieja cone is to the upper right.

Laguna de Fria (center) is seen here from the west, along a ridge near Cráter Activo. It formed when meteoric water accumulated in a depression between overlapping cones of the Rincón de la Vieja complex. Rincón de la Vieja cone is to the upper right. Photo by Cindy Stine, 1989 (U.S. Geological Survey).

Hydrothermally altered rocks and lava flows are exposed in cliffs on the Irazú upper northern flank. Las Fumaroles (near top center), a thermal area below the cliffs, was the source of an explosive eruption in December 1994 that also produced an avalanche and lahar down the Río Sucio.

Hydrothermally altered rocks and lava flows are exposed in cliffs on the Irazú upper northern flank. Las Fumaroles (near top center), a thermal area below the cliffs, was the source of an explosive eruption in December 1994 that also produced an avalanche and lahar down the Río Sucio.Photo by Eliecer Duarte, 2001 (OVSICORI-UNA).

The Platanar volcanic complex on the horizon is the NW-most volcano in the Cordillera Central of Costa Rica. The complex consists of Platanar and Porvenir, which formed within the Chocosuela caldera. This view is from the east with the Hule maar, located about 11 km north of the Poás summit, in the foreground.

The Platanar volcanic complex on the horizon is the NW-most volcano in the Cordillera Central of Costa Rica. The complex consists of Platanar and Porvenir, which formed within the Chocosuela caldera. This view is from the east with the Hule maar, located about 11 km north of the Poás summit, in the foreground.Photo by Mike Carr, 1983 (Rutgers University).

The broad massif of Poás volcano rises about 35 km to the NW above the outskirts of the city of San José. The summit of the volcano is a national park and is easily accessible by road from the capital city. The massive 2708-m-high volcano covers an area of about 300 km2 and rises about 1400 m above the central valley. Two large calderas cut its summit, and an acidic crater lake partially fills the active crater.

The broad massif of Poás volcano rises about 35 km to the NW above the outskirts of the city of San José. The summit of the volcano is a national park and is easily accessible by road from the capital city. The massive 2708-m-high volcano covers an area of about 300 km2 and rises about 1400 m above the central valley. Two large calderas cut its summit, and an acidic crater lake partially fills the active crater.Photo by Ichio Moriya (Kanazawa University).

An eruption began at Arenal on 29 July 1968 with major explosions and pyroclastic flows that destroyed two towns and killed 78 people. Three new craters formed on the west flank. This 12 August 1968 view from the WNW flank shows an ash plume with part of the devastated zone in the foreground. Effusion of lava flows that began on 19 September formed an extensive lava field on the western flank.

An eruption began at Arenal on 29 July 1968 with major explosions and pyroclastic flows that destroyed two towns and killed 78 people. Three new craters formed on the west flank. This 12 August 1968 view from the WNW flank shows an ash plume with part of the devastated zone in the foreground. Effusion of lava flows that began on 19 September formed an extensive lava field on the western flank.Photo by William Melson, 1968 (Smithsonian Institution)

Outcrops of trachyte form cliffs on the northern side of Isla Coco. Seabirds perch on lines of the R/V Searcher of the University of Costa Rica. A massive trachytic lava dome lies between Bahia Wafer and Bahia Chathan on the NE side of the island.

Outcrops of trachyte form cliffs on the northern side of Isla Coco. Seabirds perch on lines of the R/V Searcher of the University of Costa Rica. A massive trachytic lava dome lies between Bahia Wafer and Bahia Chathan on the NE side of the island. Photo by Pat Castillo, 1984 (Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California San Diego).

An ash plume above the Irazú summit crater is seen here in 1917 from the national theater in San José. All summit craters were reported to be active on 27 September 1917, after which activity steadily intensified. Ash fell in Curridabat on 18 November and again a month later, when ash also fell in Tres Ríos. On 6 January 1918 ashfall reached San José, Heredia, and Puriscal. Intermittent explosive activity continued until 1921, with an explosion on 30 November 1918 producing ashfall as far as Nicoya.

An ash plume above the Irazú summit crater is seen here in 1917 from the national theater in San José. All summit craters were reported to be active on 27 September 1917, after which activity steadily intensified. Ash fell in Curridabat on 18 November and again a month later, when ash also fell in Tres Ríos. On 6 January 1918 ashfall reached San José, Heredia, and Puriscal. Intermittent explosive activity continued until 1921, with an explosion on 30 November 1918 producing ashfall as far as Nicoya.Anonymous, 1917 (published in Alvarado, 1989).

An active lava flow with small plumes rising from the margins can be seen at the upper right descending the Arenal NNW flank from the degassing Crater C complex on 29 June 1999. Below it, descending diagonally NE to the lower right, is another recent flow with clear lateral levees. The inactive crater to the left is Crater D, the pre-1968 summit crater.

An active lava flow with small plumes rising from the margins can be seen at the upper right descending the Arenal NNW flank from the degassing Crater C complex on 29 June 1999. Below it, descending diagonally NE to the lower right, is another recent flow with clear lateral levees. The inactive crater to the left is Crater D, the pre-1968 summit crater. Photo by Federico Chavarria Kopper, 1999 (courtesy of Eduardo Malavassi, OVSICORI-UNA).

This 1964 photo shows visitors at the edge of the Irazú active crater; seven people were killed and many more injured by explosive ejecta in April and August of that year. Secondary lahars produced by the remobilization of thick ash deposits also caused fatalities. Over a 2-year period, 46 lahars occurred along the Río Reventado valley; one killed at least 20 people and destroyed 400 houses and some factories.

This 1964 photo shows visitors at the edge of the Irazú active crater; seven people were killed and many more injured by explosive ejecta in April and August of that year. Secondary lahars produced by the remobilization of thick ash deposits also caused fatalities. Over a 2-year period, 46 lahars occurred along the Río Reventado valley; one killed at least 20 people and destroyed 400 houses and some factories.Anonymous, 1964 (published in Alvarado, 1989).

The 50-m-deep Turrialba central crater (seen here looking NE) and the SW crater were the source of a large eruption in 1866. Phreatomagmatic that year produced ashfall in Costa Rica's Central Valley for four days in January, and three days in February. Ash fell as far as Puntarenas and El Realejo in Nicaragua. Pyroclastic surges traveled more than 4 km, and small lahars traveled down the Río Aquiares and presumably other valleys.

The 50-m-deep Turrialba central crater (seen here looking NE) and the SW crater were the source of a large eruption in 1866. Phreatomagmatic that year produced ashfall in Costa Rica's Central Valley for four days in January, and three days in February. Ash fell as far as Puntarenas and El Realejo in Nicaragua. Pyroclastic surges traveled more than 4 km, and small lahars traveled down the Río Aquiares and presumably other valleys.Photo by José Enrique Valverde Sanabria, 1996 (courtesy of Eduardo Malavassi, OVSICORI-UNA).

Cerro Montezuma volcano in the Tenorio volcanic complex is seen here from the SW. The Tenorio complex marks the SE limit of the Guanacaste Range, which extends NW towards the Nicaragua border. This complex of five volcanic cones along a NNW-SSE trend has a cluster of volcanic domes at its northern end. No confirmed historical eruptions have occurred at Tenorio. Despite the report of a volcanic eruption in 1816, the volcano was densely forested at the time of its December 1864 visit by Seebach.

Cerro Montezuma volcano in the Tenorio volcanic complex is seen here from the SW. The Tenorio complex marks the SE limit of the Guanacaste Range, which extends NW towards the Nicaragua border. This complex of five volcanic cones along a NNW-SSE trend has a cluster of volcanic domes at its northern end. No confirmed historical eruptions have occurred at Tenorio. Despite the report of a volcanic eruption in 1816, the volcano was densely forested at the time of its December 1864 visit by Seebach.Photo by Jorge Barquero, 1987 (OVSICORI-UNA).

The foreground crater in this aerial photo from the SW is the principal summit crater of 3432-m-high Irazú volcano. The massive stratovolcano in the background is 3340-m-high Turrialba volcano. Roads of widely divergent quality lead to the summit craters of both these historically active volcanoes, the two highest in Costa Rica.

The foreground crater in this aerial photo from the SW is the principal summit crater of 3432-m-high Irazú volcano. The massive stratovolcano in the background is 3340-m-high Turrialba volcano. Roads of widely divergent quality lead to the summit craters of both these historically active volcanoes, the two highest in Costa Rica.Copyrighted photo by Katia and Maurice Krafft, 1983.

The Viejo-Porvenir complex is seen here rising above farmlands NE of the massif. The Viejo peak is on the left and Porvenir on the right.

The Viejo-Porvenir complex is seen here rising above farmlands NE of the massif. The Viejo peak is on the left and Porvenir on the right.Photo by Eliecer Duarte (OVSICORI-UNA).

The summit of Poás volcano, seen here in 1983 from the south, contains a group of craters along a N-S line. The forested Botos cone (foreground) is filled with the waters of Laguna del Agua Fría (also known as Laguna del Poás). The unvegetated active summit crater appears at the center. A third crater cuts the south side of the forested von Frantzius cone in the background.

The summit of Poás volcano, seen here in 1983 from the south, contains a group of craters along a N-S line. The forested Botos cone (foreground) is filled with the waters of Laguna del Agua Fría (also known as Laguna del Poás). The unvegetated active summit crater appears at the center. A third crater cuts the south side of the forested von Frantzius cone in the background.Copyrighted photo by Katia and Maurice Krafft, 1983.

The Irazú summit crater is about 700 m wide and nearly 200 m deep and has been the source of most of Irazú's historical eruptions. Geothermal activity is frequently observed around of the lake, and the water color varies with changing atmospheric conditions.

The Irazú summit crater is about 700 m wide and nearly 200 m deep and has been the source of most of Irazú's historical eruptions. Geothermal activity is frequently observed around of the lake, and the water color varies with changing atmospheric conditions.Photo by Lee Siebert, 1998 (Smithsonian Institution).

Phreatic eruptions resumed from Poás in June 1987, ejecting lake water and sediments to a maximum reported height of 75 m. This 23 January 1988 photo shows the typical ejection of plumes of gas, ash, and mud above the crater lake. The crater lake disappeared by 19 April 1989 then ash emission began. Phreatic activity began again after rainwater formed a new lake. During May 1989 ash plumes reached heights of 1.5-2 km above the crater.

Phreatic eruptions resumed from Poás in June 1987, ejecting lake water and sediments to a maximum reported height of 75 m. This 23 January 1988 photo shows the typical ejection of plumes of gas, ash, and mud above the crater lake. The crater lake disappeared by 19 April 1989 then ash emission began. Phreatic activity began again after rainwater formed a new lake. During May 1989 ash plumes reached heights of 1.5-2 km above the crater.Photo by Gerardo Soto, 1988 (Instituto Costarricense de Electridad).

The flanks of Von Seebach cone (upper right) are a result of tephra and acidic gases blown downwind from the lake-filled Cráter Activo (left). Steady trade winds from the NNE distribute gas from Active Crater to the SW, creating the "Dead Zone" that extends down the SW flanks to the upper right.

The flanks of Von Seebach cone (upper right) are a result of tephra and acidic gases blown downwind from the lake-filled Cráter Activo (left). Steady trade winds from the NNE distribute gas from Active Crater to the SW, creating the "Dead Zone" that extends down the SW flanks to the upper right.Photo by Eliecer Duarte (OVSICORI-UNA).

An ash plume rises above the crater lake of Poás volcano in 1915. Intermittent eruptions producing ashfall during 8 October 1914 to 15 May 1915. The 10 April eruption was seen from San José, and the last of a series of eruptions during 15-19 April that produced ashfall across great distances.

An ash plume rises above the crater lake of Poás volcano in 1915. Intermittent eruptions producing ashfall during 8 October 1914 to 15 May 1915. The 10 April eruption was seen from San José, and the last of a series of eruptions during 15-19 April that produced ashfall across great distances.Photo by R. Fernandez Peralta, 1915 (courtesy of Jorge Barquero, Universidad Nacional Costa Rica).

Erosional remnants of the widespread pyroclastic rock unit at the NW corner of Cocos Island form small offshore islets. Pyroclastic rock units are thickest at the NE side of the island, south of the large trachytic lava dome between Bahia Wafer and Bahia Chathan, but are also exposed along the NW, SW, and southern coasts, and in the SW and eastern interior of the island.

Erosional remnants of the widespread pyroclastic rock unit at the NW corner of Cocos Island form small offshore islets. Pyroclastic rock units are thickest at the NE side of the island, south of the large trachytic lava dome between Bahia Wafer and Bahia Chathan, but are also exposed along the NW, SW, and southern coasts, and in the SW and eastern interior of the island.Photo by Pat Castillo, 1984 (Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California San Diego).

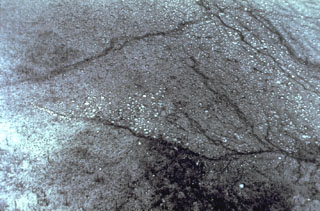

This is a pyroclastic flow deposit that was emplaced down the NE flank of Arenal on 5 September 2003, singeing vegetation on either side of the narrow valley. A series of pyroclastic flows were produced over two hours starting at 1055. The pyroclastic flows originated from the collapse of lava flows on the steep upper flank. Accompanying ashfall occurred to the W and NW.

This is a pyroclastic flow deposit that was emplaced down the NE flank of Arenal on 5 September 2003, singeing vegetation on either side of the narrow valley. A series of pyroclastic flows were produced over two hours starting at 1055. The pyroclastic flows originated from the collapse of lava flows on the steep upper flank. Accompanying ashfall occurred to the W and NW.Photo by Eliecer Duarte, 2003 (OVSICORI-UNA).

Barva volcano (also spelled Barba) rises to the NE above the western outskirts of San José. The volcano lies about 22 km north of the city. Three peaks along the broad summit ridge give rise to the name Las Tres Marías (The Three Marias). No confirmed historical eruptions are known from Barva, but thermal springs are found near Porrosati de Barva, Gongolona peak, and along ridges to the north side of the volcano. Sulfur vapor and mineral deposition occurs at landslide scarps on the flanks of the volcano.

Barva volcano (also spelled Barba) rises to the NE above the western outskirts of San José. The volcano lies about 22 km north of the city. Three peaks along the broad summit ridge give rise to the name Las Tres Marías (The Three Marias). No confirmed historical eruptions are known from Barva, but thermal springs are found near Porrosati de Barva, Gongolona peak, and along ridges to the north side of the volcano. Sulfur vapor and mineral deposition occurs at landslide scarps on the flanks of the volcano.Photo by Ichio Moriya (Kanazawa University).