Chile Volcanoes

A map display is currently under development.

Chile has 90 Holocene volcanoes. Note that as a scientific organization we provide these listings for informational purposes only, with no international legal or policy implications. Volcanoes will be included on this list if they are within the boundaries of a country, on a shared boundary or area, in a remote territory, or within a maritime Exclusive Economic Zone. Bolded volcanoes have erupted within the past 20 years. Suggestions and data updates are always welcome ().

| Volcano Name | Last Eruption | Volcanic Region | Primary Landform |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acamarachi | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Aguilera | 1253 BCE | Austral Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Antillanca Volcanic Complex | 230 BCE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Antuco | 1869 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Apagado | 590 BCE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Cerro Azul | 1967 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cerro Bayo Gorbea | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Lomas Blancas | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Monte Burney | 1910 CE | Austral Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Caburgua-Huelemolle | 5050 BCE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Cluster |

| Caichinque | Unknown - Evidence Uncertain | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Calabozos | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Calbuco | 2015 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Callaqui | 1980 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Carran-Los Venados | 1979 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Cluster |

| Cay | Unknown - Evidence Uncertain | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cayutue-La Vigueria | 190 BCE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Cluster |

| Chaiten | 2011 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Caldera |

| Chiliques | Unknown - Evidence Uncertain | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Nevados de Chillan | 2022 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Colachi | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Copahue | 2024 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Corcovado | 4920 BCE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cordon de Puntas Negras | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cordon del Azufre | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Corrida de Cori Volcanic Field | Unknown - Evidence Uncertain | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Descabezado Grande | 1933 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Falso Azufre | Unknown - Evidence Uncertain | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Fueguino | 1820 CE | Austral Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor (Silicic) |

| Guallatiri | 1960 CE | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Guayaques | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Hornopiren | 340 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cerro Hudson | 2011 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Huequi | 1920 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Nevado de Incahuasi | Unknown - Evidence Uncertain | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Irruputuncu | 1995 CE | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Isluga | 1913 CE | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Lanin | 560 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

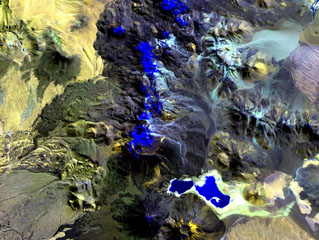

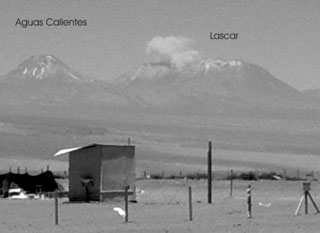

| Lascar | 2023 CE | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Lastarria | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Lautaro | 1979 CE | Austral Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Licancabur | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Llaima | 2009 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Llullaillaco | 1877 CE | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Nevado de Longavi | 4890 BCE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Lonquimay | 1990 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Maca | 1560 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Maipo | 1912 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Laguna del Maule | 50 BCE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Caldera |

| Melimoyu | 200 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Mentolat | 1710 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Meullin | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Cluster |

| Michinmahuida | 1835 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Miniques | Unknown - Evidence Uncertain | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Mocho-Choshuenco | 1937 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| La Negrillar | Unknown - Evidence Uncertain | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Sierra Nevada | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Nevados Ojos del Salado | 750 CE | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Olca-Paruma | Unknown - Eruption Observed | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Osorno | 1869 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Pali-Aike Volcanic Field | 5550 BCE | Austral Andean Volcanic Arc | Cluster |

| Palomo | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Parinacota | 290 CE | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 2019 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Pular | Unknown - Evidence Uncertain | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Puntiagudo-Cordon Cenizos | 1850 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Purico Complex | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Shield |

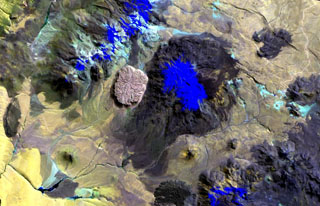

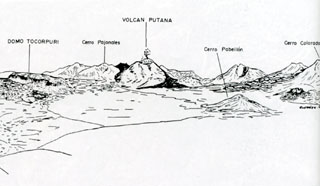

| Putana | 1810 CE | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 2012 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Puyuhuapi | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Quetrupillan | 255 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Rapa Nui | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Salas y Gómez Ridge Volcano Group | Shield |

| Reclus | 1908 CE | Austral Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Volcan Resago | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor (Basaltic) |

| Sairecabur | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| San Jose | 1960 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| San Pedro-Pellado | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Socompa | 5250 BCE | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Sollipulli | 1240 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Caldera |

| El Solo | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Taapaca | 320 BCE | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Tilocalar | Unknown - Evidence Uncertain | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Tinguiririca | 1917 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Tolhuaca | 4000 BCE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Tronador | Unknown - Evidence Uncertain | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cerro Tujle | Unknown - Evidence Credible | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Tupungatito | 1987 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Villarrica | 2025 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Yanteles | 6650 BCE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Yate | 1090 CE | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

Chronological listing of known Holocene eruptions (confirmed or uncertain) from volcanoes in Chile. Bolded eruptions indicate continuing activity.

| Volcano Name | Start Date | Stop Date | Certainty | VEI | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copahue | 2024 Oct 16 ± 1 days | 2024 Oct 27 ± 1 days | Confirmed | Observations: Reported | |

| Lascar | 2022 Dec 10 | 2023 Feb 3 ± 1 days | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | 2021 Jul 2 | 2021 Nov 6 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | 2020 Jun 16 | 2020 Nov 2 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | 2019 Aug 2 | 2019 Nov 12 (?) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 2018 Nov 7 (on or before) | 2019 May 7 ± 1 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | 2017 Jun 4 | 2018 Dec 7 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 2016 Jan 8 | 2022 Oct 17 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 2015 Oct 30 | 2017 Apr 2 ± 1 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | 2015 Sep 18 ± 3 days | 2017 Feb 22 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Calbuco | 2015 Apr 22 | 2015 May 26 | Confirmed | 4 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 2014 Dec 2 ± 7 days | 2025 Apr 19 (continuing) | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | 2014 Jul 4 | 2014 Dec 2 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 2013 Jul 25 | 2013 Jul 29 (?) | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 2013 Apr 2 | 2013 Nov 20 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | 2012 Dec 22 | 2013 Dec 10 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | [2012 Nov 14] | [2012 Nov 14 (?)] | Uncertain | ||

| Copahue | 2012 Jul 17 | 2012 Jul 19 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Callaqui | [2012 Jan 2] | [2012 Jan 2] | Uncertain | ||

| Cerro Hudson | 2011 Oct 26 | 2011 Nov 1 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 2011 Jun 4 | 2012 Apr 21 (?) | Confirmed | 5 | Observations: Reported |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 2011 Feb 17 | 2011 Jun 26 ± 1 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 2010 Sep 6 | 2010 Oct 13 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 2009 Nov 22 | 2012 Apr 20 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 2009 Jan 29 | 2009 Mar 24 (?) | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Callaqui | [2009 Jan 22] | [2009 Jan 22] | Uncertain | ||

| Nevados de Chillan | [2009 Jan 21] | [2009 Jan 22] | Uncertain | ||

| Villarrica | 2008 Oct 26 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Chaiten | 2008 May 2 | 2011 May 31 ± 3 days | Confirmed | 4 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 2008 Jan 1 | 2009 Jun 12 ± 4 days | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 2007 May 26 | 2007 Aug 8 (?) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 2006 Apr 18 | 2007 Jul 18 (?) | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 2005 May 4 | 2005 May 4 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 2004 Aug 5 (?) | 2007 Dec 24 (?) | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | [2003 Dec 9] | [2003 Dec 9] | Uncertain | ||

| Nevados de Chillan | 2003 Aug 29 | 2003 Sep 15 ± 5 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 2003 May 23 (?) | 2004 Mar 25 (?) | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 2003 Apr 9 | 2003 Apr 16 (on or after) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 2002 Oct 26 | 2002 Oct 27 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 2002 Oct 13 ± 12 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | [2001 May 17 (?)] | [2001 Jul 5 (?)] | Uncertain | ||

| Lascar | 2000 Jul 20 | 2001 Jan 18 (?) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | 2000 Jul 1 | 2000 Oct 18 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 1998 Nov 18 | 1998 Nov 21 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1998 Nov 10 ± 3 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1998 Apr 3 | 1998 Apr 23 (?) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1998 Feb 24 ± 4 days | 2002 Jun 16 (?) ± 15 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1997 Mar 16 (?) ± 15 days | 1997 Oct 16 (?) ± 15 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 1996 Oct 18 | 1996 Oct 18 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1996 Sep 14 | 1997 Aug 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1996 Jan 16 ± 15 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1995 Oct 13 | 1995 Oct 22 (on or after) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | 1995 Sep 16 ± 15 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Irruputuncu | 1995 Sep 1 | 1995 Sep 26 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1995 Apr 15 ± 5 days | 1995 Jun 2 (on or after) | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | 1994 Dec 16 ± 15 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 1994 Nov 13 | 1995 Jul 20 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1994 Sep 26 | 1994 Dec 30 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 1994 Jul 20 | 1994 Jul 26 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1994 May 17 | 1994 Aug 30 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Tinguiririca | [1994 Jan 15] | [1994 Jan 15] | Uncertain | ||

| Lascar | 1993 Dec 17 | 1994 Feb 27 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados Ojos del Salado | [1993 Nov 14] | [1993 Nov 14] | Uncertain | ||

| Lascar | 1993 Jan 30 | 1993 Aug 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 4 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1992 Sep 11 | 1992 Dec 16 (on or after) ± 15 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1992 Aug 23 | 1992 Sep 2 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | 1992 Jul 22 | 1993 Jul 2 ± 182 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 1991 Oct 21 | 1992 May 23 (?) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1991 Aug 30 | 1991 Sep 17 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Cerro Hudson | 1991 Aug 8 | 1991 Oct 27 | Confirmed | 5 | Observations: Reported |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 1991 Feb 9 | 1991 Mar 2 ± 2 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 1990 Nov 24 | 1990 Nov 24 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 1990 Jul 2 ± 182 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Pular | [1990 Apr 24] | [1990 Apr 24] | Uncertain | ||

| Llaima | 1990 Feb 25 | 1990 Nov 25 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Irruputuncu | [1989 Dec 16 ± 15 days] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Lonquimay | 1988 Dec 25 | 1990 Jan 24 ± 1 days | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | 1987 Nov 28 | 1987 Nov 30 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 1987 Nov 16 (on or before) ± 15 days | 1990 Apr 6 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 1986 Sep 14 | 1986 Sep 16 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | 1986 Jan 20 | 1986 Jan 20 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Guallatiri | [1985 Dec 1] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Lascar | 1984 Dec 16 ± 15 days | 1985 Jul 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 0 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1984 Aug 11 | 1985 Nov 18 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1984 Apr 20 | 1984 Nov 26 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1983 Oct 14 | 1983 Oct 16 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Callaqui | 1980 Oct 16 ± 15 days | 1980 Oct 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1980 Jun 20 | 1980 Sep 24 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | 1980 Jan 10 | 1980 Jan 11 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1979 Oct 15 | 1979 Nov 28 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Carran-Los Venados | 1979 Apr 14 | 1979 May 20 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lautaro | 1979 Mar 8 (on or before) | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lautaro | 1978 Jun 16 ± 15 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1977 Jan 26 | 1977 Jan 30 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | [1974 Jul 16 ± 15 days] | [1974 Sep 16 ± 15 days] | Uncertain | ||

| Nevados de Chillan | 1973 Jul 16 ± 15 days | 1986 Jul 2 ± 182 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Calbuco | 1972 Aug 26 | 1972 Aug 26 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lautaro | 1972 Jul 2 ± 182 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | [1972 Jul 2 ± 182 days] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Lascar | [1972 Jul 2 ± 182 days] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Putana | [1972 Jul 2 ± 182 days] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Llaima | 1971 Dec 1 ± 30 days | 1972 Mar 12 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1971 Oct 29 | 1972 Feb 21 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Cerro Hudson | 1971 Aug 12 | 1971 Sep 18 (on or after) | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 1969 May 16 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | 1968 Jul 2 ± 182 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Cerro Azul | 1967 Aug 9 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Planchon-Peteroa | [1967 Feb 16 ± 15 days] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Nevados de Chillan | [1965 Jul 2 ± 182 days] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Tupungatito | 1964 Aug 3 | 1964 Sep 19 (on or after) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1964 Jul 2 ± 182 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1964 Mar 2 | 1964 Apr 21 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1963 Feb 25 (?) | 1963 Sep 21 (on or after) | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 1962 Jan 16 ± 15 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Lautaro | 1961 Oct 16 ± 15 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1961 Jul 2 ± 182 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | 1961 Jul 2 ± 182 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | 1961 May 5 ± 4 days | 1961 Aug 16 (on or after) ± 15 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Calbuco | 1961 Feb 1 | 1961 Mar 26 (on or after) | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Guallatiri | 1960 Dec 2 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| San Pedro-San Pablo | [1960 Dec 2] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Tupungatito | 1960 Jul 15 ± 5 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 1960 Jul 10 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | 1960 Jul 2 ± 182 days | Unknown | Confirmed | Observations: Reported | |

| San Jose | 1960 Jul 2 ± 182 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Isluga | [1960 Jul 2 ± 182 days] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Villarrica | [1960 Jul 2 ± 182 days] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Llaima | [1960 Jul 2 ± 182 days] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 1960 May 24 | 1960 Jul 30 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Lautaro | 1959 Dec 28 | 1960 Jan 20 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 1959 Nov 16 ± 15 days | 1968 Jan 31 (on or after) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 1959 Nov 6 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | 1959 Oct 16 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Guallatiri | 1959 Jul 15 ± 5 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| San Jose | 1959 Jul 2 ± 182 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | 1959 Mar 26 ± 5 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1958 Nov 6 | 1959 Dec 21 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | 1958 Jan 16 ± 15 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1956 Oct 3 | 1956 Nov 16 ± 45 days | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1955 Oct 22 | 1957 Nov 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Carran-Los Venados | 1955 Jul 27 | 1955 Nov 12 | Confirmed | 4 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 1954 Jun 16 ± 15 days | 1954 Jul 16 ± 15 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 1951 Nov 16 ± 15 days | 1952 Feb 19 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | [1950 Jul 2 ± 182 days] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Llaima | 1949 Sep | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Cerro Azul | 1949 Apr 15 ± 5 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1948 Oct 9 | 1949 Feb 3 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1948 Apr 10 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1947 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1946 Jul 23 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1946 | 1947 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | 1946 | 1947 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1945 Mar 31 | 1945 Apr 3 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Lautaro | 1945 Jan 15 ± 45 days | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Calbuco | 1945 | Unknown | Confirmed | Observations: Reported | |

| Nevados de Chillan | [1945] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Copahue | 1944 | Unknown | Confirmed | Observations: Reported | |

| Llaima | 1944 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1942 Jun 9 | 1942 Nov | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1941 Jun 23 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lonquimay | [1940 Feb] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Lascar | 1940 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1938 Dec 1 ± 30 days | 1939 Feb 1 ± 30 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1938 Dec | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 1938 Sep | 1938 Oct | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | [1938 Feb 11] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| San Pedro-San Pablo | [1938 Feb] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Callaqui | [1937 Sep 18] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Tacora | [1937 Aug 5] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Mocho-Choshuenco | 1937 Jun 16 | Unknown | Confirmed | Observations: Reported | |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 1937 Apr | 1937 May 5 ± 4 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1937 Feb 9 (?) | 1937 Nov 2 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | 1937 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1935 Dec 1 ± 30 days | 1936 Jun 27 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1935 Jul 2 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 1934 Mar 6 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1934 Jan 17 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 1933 Oct 9 | 1933 Dec | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lautaro | 1933 Feb | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1933 Jan 5 | 1933 Jan 18 ± 12 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lonquimay | 1933 Jan 4 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Cerro Azul | 1933 | 1938 Jul 25 (?) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1932 Dec 31 | 1933 Jan 5 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Descabezado Grande | 1932 Jun 5 ± 5 days | 1933 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1932 Mar 2 | 1932 Mar 2 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Calbuco | 1932 | Unknown | Confirmed | Observations: Reported | |

| Llaima | 1930 Jul 6 | 1930 Aug 20 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Puntiagudo-Cordon Cenizos | [1930] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Tacora | [1930] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Villarrica | 1929 Dec 27 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1929 Dec | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 1929 Jan 7 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Calbuco | 1929 Jan 6 | 1929 Jan 6 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1928 Nov 30 | 1929 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1927 Oct 5 | 1927 Dec 5 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1927 Apr 10 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1927 | 1928 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | 1925 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| San Pedro-San Pablo | [1923] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Nevados de Chillan | [1923] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Villarrica | 1922 Oct 24 | 1922 Nov 27 ± 20 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1922 Oct 24 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 1921 Dec 13 | 1922 Feb 12 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | [1921 Dec 10] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Villarrica | 1920 Dec 10 | 1920 Dec 13 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Huequi | 1920 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | [1919] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 1919 | 1920 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Calbuco | 1917 Apr | 1917 May | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1917 Feb 4 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| San Pedro-San Pablo | [1917] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Tinguiririca | 1917 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| San Pedro-San Pablo | [1916] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Cerro Azul | 1916 | 1932 Apr 21 | Confirmed | 5 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1915 | 1918 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Michinmahuida | [1915 ± 25 years] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Cerro Azul | 1914 Sep 8 | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1914 Jul 3 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 1914 Feb 8 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1914 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Cerro Azul | [1913 Jan 15 ± 45 days] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Isluga | 1913 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Guallatiri | 1913 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Cerro Azul | 1912 Feb | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Maipo | 1912 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1912 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| San Pedro-San Pablo | [1911 Sep] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Calbuco | 1911 | 1912 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Monte Burney | 1910 Mar | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1909 Aug 19 | 1910 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Calbuco | 1909 Mar | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1908 Oct 31 | 1908 Dec 12 (?) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Reclus | 1908 ± 1 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Maipo | [1908] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Guallatiri | [1908] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Cerro Azul | 1907 Jul 28 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1907 May 5 ± 4 days | 1907 May 26 (?) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Calbuco | 1907 Apr 22 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Carran-Los Venados | 1907 Apr 9 | 1908 Feb (on or after) | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | 1907 Feb 15 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1907 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1907 | 1908 Mar | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1906 Aug 6 | 1906 Dec | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1906 Apr 22 | 1906 Dec | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Calbuco | 1906 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Huequi | 1906 | 1907 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Cerro Azul | 1906 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Maipo | 1905 Oct 28 | 1905 Oct 30 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 1905 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1904 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Ollague | [1903 Dec 8] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Llaima | 1903 May 12 | 1903 May 14 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Cerro Azul | [1903 Jan] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Lascar | 1902 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1902 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| San Pedro-San Pablo | [1901 May 25] | [1901 Aug] | Uncertain | ||

| Tupungatito | 1901 Apr | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Huequi | 1900 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 1898 | 1900 (?) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1898 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1897 Dec 1 ± 30 days | 1898 Feb 1 ± 30 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | 1897 Jan | 1897 Apr 12 (on or after) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Huequi | 1896 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1895 | 1896 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| San Jose | 1895 | 1897 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Calbuco | 1894 Nov 16 | 1895 (?) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1893 Dec 1 ± 30 days | 1894 Feb 1 ± 30 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1893 Dec | 1894 Dec | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1893 Mar 4 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Calbuco | 1893 Jan 7 | 1894 Jan 16 (on or after) | Confirmed | 4 | Observations: Reported |

| Huequi | 1893 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 1893 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1892 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1891 Feb | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| San Pedro-San Pablo | [1891 (?)] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Cerro Hudson | 1891 | Unknown | Confirmed | Observations: Reported | |

| Huequi | 1890 | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1890 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 1889 Sep | 1894 (?) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1889 Apr 20 | 1889 Jul | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| San Jose | 1889 | 1890 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | 1889 | 1890 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lonquimay | 1887 Jun 2 | 1890 Jan | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1887 Jan 16 | 1887 Jun 24 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Isluga | 1885 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | [1883 Jan 21] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Lascar | 1883 | 1885 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1883 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1883 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | [1881] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| San Jose | 1881 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Maipo | [1881] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Villarrica | 1880 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1879 Feb 2 | 1879 Mar | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Reclus | 1879 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lautaro | 1879 | Unknown | Confirmed | Unknown | |

| Isluga | 1878 Feb | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lautaro | [1878 Jan 18] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Planchon-Peteroa | 1878 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llullaillaco | 1877 May | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1877 Mar 12 | 1877 May | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1877 Feb 12 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1877 Jan 16 | 1877 Jun 24 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Isluga | 1877 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| San Pedro-San Pablo | [1877 (?)] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Lautaro | 1876 Oct | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1875 Nov 17 | 1876 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1875 | 1876 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 1875 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1874 Apr 16 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | [1874] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Nevados de Chillan | 1872 Jul 22 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1872 Jun 6 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Quetrupillan | [1872 Jun 6] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Planchon-Peteroa | [1872] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Villarrica | 1871 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| San Pedro-San Pablo | [1870] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Maipo | [1869 Aug 24] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Isluga | 1869 Aug | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1869 Apr | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1869 Feb 4 | 1869 Feb 24 ± 4 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Reclus | 1869 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Osorno | 1869 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Antuco | 1869 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Planchon-Peteroa | [1869] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Llullaillaco | 1868 Sep | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Observations: Reported |

| Isluga | 1868 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | 1867 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | [1867] | [1868] | Uncertain | ||

| Llaima | 1866 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Olca-Paruma | [1865] | [1867] | Uncertain | ||

| Nevados de Chillan | 1864 Nov 30 | 1865 Feb 3 ± 1 days | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Mocho-Choshuenco | 1864 Nov 1 | 1864 Nov 3 ± 1 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1864 Oct | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Callaqui | [1864 Oct] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Llaima | 1864 | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Antuco | 1863 Dec | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Isluga | 1863 Aug | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Antuco | [1862 Jan] | [1862 Mar 3] | Uncertain | ||

| Llaima | 1862 | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1861 Jun | 1863 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Antuco | 1861 Feb (?) | 1861 Aug (?) | Confirmed | 0 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | 1861 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1860 Jul 25 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 1860 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1859 May 19 | 1860 Apr 12 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 1858 Apr | 1858 Dec | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Osorno | 1855 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llullaillaco | 1854 Feb 10 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | 1854 Jan 20 | 1854 Jan 30 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1853 Nov | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Lonquimay | 1853 Feb | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Lascar | [1853] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Antuco | 1852 Nov | 1853 Jan | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1852 | 1853 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | [1852] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Osorno | 1851 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Puntiagudo-Cordon Cenizos | 1850 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1850 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Antuco | [1848] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Lascar | 1848 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Cerro Azul | 1846 Nov 26 | 1853 (?) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Antuco | 1845 Feb 26 | 1845 Mar 1 (on or after) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Planchon-Peteroa | [1842] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Villarrica | 1841 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Seamount JF6 | [1839 Feb 12] | [1839 Feb 13] | Uncertain | ||

| Antuco | [1839] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| San Jose | 1838 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1837 Nov 7 | 1837 Nov 21 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Osorno | 1837 Nov 7 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 1837 Feb | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Maipo | [1837] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Villarrica | 1836 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Corcovado | [1835 Nov 11] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Yanteles | [1835 Feb 20] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Michinmahuida | 1835 Feb 20 | 1835 Mar 15 ± 5 days | Confirmed | 0 | Observations: Reported |

| Robinson Crusoe | 1835 Feb 20 | 1835 Feb 21 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | [1835] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Maipo | [1835] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Planchon-Peteroa | 1835 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Hornopiren | [1835] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Osorno | 1834 Nov 29 | 1835 Feb 24 ± 4 days | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Michinmahuida | 1834 Nov 25 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Corcovado | [1834 Nov] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Maipo | [1833] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Villarrica | 1832 Dec 24 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Maipo | [1831 Feb 16] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Maipo | 1829 Sep 26 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Tupungatito | 1829 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Antuco | 1828 Dec 18 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Maipo | 1826 Mar 1 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1826 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Guallatiri | 1825 ± 25 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| San Jose | 1822 Nov 19 | 1838 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1822 Nov 19 | 1822 Nov 25 ± 5 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Maipo | [1822] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Llaima | 1822 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Fueguino | 1820 Nov 25 | 1820 Nov 26 (on or after) | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Antuco | 1820 | 1821 (?) | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1815 | 1818 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Putana | 1810 ± 10 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Observations: Reported | |

| Antuco | 1806 May (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1806 Apr | 1806 May | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1798 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Calbuco | 1792 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Observations: Reported | |

| Osorno | 1790 Mar 9 | 1791 Dec 26 ± 5 days | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1790 Jan | 1801 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Maipo | [1788] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Villarrica | 1787 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1780 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1777 | 1779 | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | [1775] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Michinmahuida | [1775 ± 40 years] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Villarrica | 1771 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1767 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Osorno | 1765 ± 14 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 1762 Dec 3 | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1761 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1759 Dec | 1759 Dec | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1759 Dec | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | [1759 (?)] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 1759 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Antuco | 1752 Jan 31 | 1752 Feb 1 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1752 Jan 30 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Callaqui | 1751 Dec 31 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Llaima | 1751 Dec 18 | 1752 | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1751 Dec 14 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 1751 Nov | 1751 Dec | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Antuco | 1750 ± 10 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Copahue | 1750 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1749 (?) | 1751 | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1745 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Robinson Crusoe | [1743] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Villarrica | 1742 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Michinmahuida | 1742 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Cerro Hudson | 1740 ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Villarrica | 1737 Dec 24 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1730 Jul 8 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1721 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Osorno | 1719 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1716 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1715 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Fueguino | [1712 Nov 26 ± 4 days] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Mentolat | 1710 ± 5 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Observations: Reported | |

| Villarrica | 1709 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1708 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1705 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Huequi | 1695 ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Villarrica | 1688 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1682 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1675 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1672 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1669 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 1660 | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1657 Mar 15 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Michinmahuida | [1650 ± 50 years] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Nevados de Chillan | 1650 ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1647 May 13 | Unknown | Confirmed | 1 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1645 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Osorno | 1644 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1642 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | [1640 Feb 3] | [Unknown] | Uncertain | ||

| Llaima | 1640 Feb | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Observations: Reported |

| Osorno | 1640 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Chaiten | 1640 ± 18 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Villarrica | 1638 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1632 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1625 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1617 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1612 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1610 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1604 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Calbuco | 1600 ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Villarrica | 1600 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1594 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1584 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1582 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1579 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Osorno | 1575 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1564 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1562 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Maca | 1560 ± 110 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Villarrica | 1558 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Observations: Reported |

| Villarrica | 1553 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Michinmahuida | 1550 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Villarrica | 1543 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1539 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1538 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1537 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1526 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1523 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1521 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1516 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1515 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1509 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1503 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1497 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1494 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1492 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1483 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1479 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1474 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1471 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1466 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1463 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1454 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1448 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1433 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1417 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1413 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1410 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1404 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1392 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1388 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Villarrica | 1384 | Unknown | Confirmed | 2 | Sidereal: Varve Count |

| Calbuco | 1380 ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Osorno | 1310 ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Sollipulli | 1240 ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Osorno | 1220 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 1220 ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 1140 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Yate | 1090 ± 60 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Osorno | 0910 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 0900 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Cerro Hudson | 0860 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 0860 ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Nevados Ojos del Salado | 0750 ± 250 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Calbuco | 0710 ± 60 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Michinmahuida | 0700 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Lanin | 0560 ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Calbuco | 0520 ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 0500 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Osorno | 0420 ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Maca | 0410 ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Lanin | 0400 ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Cerro Hudson | 0390 ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Hornopiren | 0340 ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Villarrica | 0330 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Parinacota | 0290 ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Isotopic: Cosmic Ray Exposure |

| Quetrupillan | 0255 ± 48 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Calbuco | 0220 ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Melimoyu | 0200 ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Calbuco | 0160 ± 135 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 0140 ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 0110 ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Villarrica | 0110 (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Parinacota | 0090 ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Anthropology | |

| Lanin | 0090 ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Calbuco | 0040 ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Quetrupillan | 0035 ± 35 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Laguna del Maule | 0050 BCE (in or before) | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Isotopic: Uranium-series |

| Lanin | 0080 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Monte Burney | 0090 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Calbuco | 0100 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Cerro Hudson | 0120 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Cayutue-La Vigueria | 0190 BCE (?) ± 190 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Osorno | 0210 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Lanin | 0220 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Antillanca Volcanic Complex | 0230 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Copahue | 0250 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Laguna del Maule | 0250 BCE | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Isotopic: Ar/Ar |

| Taapaca | 0320 BCE ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Nevados de Chillan | 0320 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Calbuco | 0330 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 0490 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Lanin | 0590 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Apagado | 0590 BCE ± 175 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Villarrica | 0670 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Cerro Hudson | 0790 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Monte Burney | 0800 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Melimoyu | 0820 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Sollipulli | 0920 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Antillanca Volcanic Complex | 0960 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 0990 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Villarrica | 1080 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Parinacota | 1100 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: Cosmic Ray Exposure | |

| Villarrica | 1230 BCE ± 40 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Aguilera | 1253 BCE ± 126 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 1490 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Nevados de Chillan | 1510 BCE ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Laguna del Maule | 1550 BCE | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Isotopic: Ar/Ar |

| Taapaca | 1580 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Osorno | 1710 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Villarrica | 1810 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Reclus | 1830 BCE (in or after) | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Taapaca | 1860 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Cerro Hudson | 1890 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 6 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Calbuco | 1920 BCE ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Villarrica | 1980 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Villarrica | 2140 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Villarrica | 2240 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Cerro Hudson | 2250 BCE (in or before) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Monte Burney | 2320 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Taapaca | 2400 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Aguilera | 2610 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Taapaca | 2950 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Villarrica | 2990 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Chaiten | 3100 BCE ± 220 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 3250 BCE ± 2400 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: Ar/Ar | |

| Nevados de Chillan | 3660 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Hornopiren | 3720 BCE ± 175 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Villarrica | 3730 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Monte Burney | 3740 BCE ± 10 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Cerro Hudson | 3890 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Tolhuaca | 4000 BCE (in or after) | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Uncertain |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 4230 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Calbuco | 4300 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Parinacota | 4320 BCE ± 1200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: Cosmic Ray Exposure | |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 4450 BCE ± 900 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: Ar/Ar | |

| Laguna del Maule | 4450 BCE | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Isotopic: Ar/Ar |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 4460 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Taapaca | 4620 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 4690 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Cerro Hudson | 4750 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 6 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Tolhuaca | 4885 BCE ± 243 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Uncertain |

| Nevado de Longavi | 4890 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Corcovado | 4920 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Cerro Hudson | 4960 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Mentolat | 5010 BCE ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Calbuco | 5030 BCE ± 180 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Caburgua-Huelemolle | 5050 BCE ± 1000 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Planchon-Peteroa | 5080 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Puyehue-Cordon Caulle | 5080 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Lascar | 5150 BCE ± 1250 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Isotopic: Cosmic Ray Exposure |

| Socompa | 5250 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Llaima | 5290 BCE ± 180 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Tolhuaca | 5371 BCE ± 243 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Uncertain |

| Taapaca | 5490 BCE ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Michinmahuida | 5500 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Pali-Aike Volcanic Field | 5550 BCE ± 2500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Anthropology | |

| Calbuco | 5820 BCE ± 880 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Parinacota | 5840 BCE ± 50 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Tolhuaca | 5857 BCE ± 243 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Uncertain |

| Corcovado | 6030 BCE ± 100 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Calbuco | 6300 BCE ± 1035 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Lanin | 6340 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Corcovado | 6640 BCE ± 770 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Yanteles | 6650 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Chaiten | 6650 BCE ± 1300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Villarrica | 6690 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Calbuco | 6760 BCE ± 825 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Copahue | 6820 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Llaima | 6880 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) |

| Nevados de Chillan | 6890 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Yanteles | 7240 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Lascar | 7250 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Monte Burney | 7390 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Llaima | 7410 BCE ± 300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Monte Burney | 7450 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Villarrica | 7520 BCE ± 900 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 0 | Correlation: Tephrochronology |

| Calbuco | 7550 BCE ± 45 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 4 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Chaiten | 7750 BCE ± 200 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Antuco | 7750 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Taapaca | 7900 BCE ± 75 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Calbuco | 7930 BCE ± 275 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Parinacota | 7950 BCE | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: Ar/Ar | |

| Calbuco | 7990 BCE ± 290 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Cerro Hudson | 8010 BCE (?) | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (uncalibrated) | |

| Calbuco | 8100 BCE ± 1300 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Calbuco | 8210 BCE ± 290 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Calbuco | 8320 BCE ± 250 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Correlation: Tephrochronology | |

| Michinmahuida | 8400 BCE ± 150 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 6 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Calbuco | 8460 BCE ± 155 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 5 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Lanin | 9240 BCE ± 500 years | Unknown | Confirmed | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) | |

| Quetrupillan | 10658 BCE ± 29 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

| Quetrupillan | 11345 BCE ± 932 years | Unknown | Confirmed | 3 | Isotopic: 14C (calibrated) |

Chile has 68 Pleistocene volcanoes. Note that as a scientific organization we provide these listings for informational purposes only, with no international legal or policy implications. Volcanoes will be included on this list if they are within the boundaries of a country, on a shared boundary or area, in a remote territory, or within a maritime Exclusive Economic Zone. Suggestions and data updates are always welcome ().

| Volcano Name | Volcanic Region | Primary Landform |

|---|---|---|

| Acotango | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Aguas Delgadas | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Alexander Selkirk | Juan Fernandez Hotspot Volcano Group | Shield |

| Apagado | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Arintica | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cerro Ascotan | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Aucanquilcha | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cerro del Azufre | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| El Azufre | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Unknown |

| Cañapa | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Capur | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Caquena | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Cerro Cariquima | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Copa-Ocana | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Copiapo | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cuernos del Diablo | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Curutu | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Deslinde | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Hecar | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Inacalari | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Incaguasi | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Unknown |

| Laco | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Volcan Larancagua | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Lejia | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cerro del Leon | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Lexone | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Volcan Linzor | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Losloyo | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cerro Maichín | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Laguna Marinaqui | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Miscanti | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cerro Napa | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Negros de Aras | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Cluster |

| Sierra Nevada | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cerro de la Niebla | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Ollague | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cerro Overo | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Paniri | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cerro Pantoja | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Los Patos | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Piedra Parada | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Nevado de los Piuquenes | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Poquis | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Porquesa | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Potor | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Puelche Volcanic Field | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Cluster |

| Quinchilca | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Rio Murta | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| Cerro de Rio Negro | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Robinson Crusoe | Juan Fernandez Hotspot Volcano Group | Shield |

| Salas y Gomez | Salas y Gómez Ridge Volcano Group | Shield |

| San Felix | San Felix Hotspot Volcano Group | Shield |

| San Francisco | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| San Pedro-San Pablo | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Seamount JF6 | Juan Fernandez Hotspot Volcano Group | Minor |

| Sordo Lucas | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Tacora | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cerro Tatajachura | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Volcan Tatio | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cerros de Tocorpuri | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cerro Trautrén | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Tres Cruces | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Tumisa | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Tupungato | Southern Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Laguna Verde | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Vilacollo | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Minor |

| El Volcan | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

| Cerro Zapaleri | Central Andean Volcanic Arc | Composite |

There are 253 photos available for volcanoes in Chile.

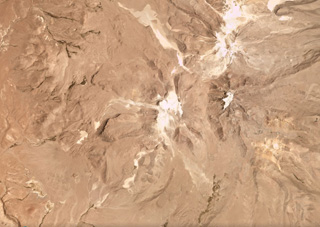

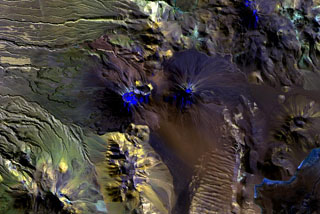

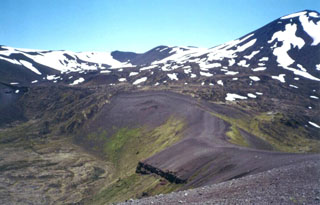

The elongated Taapaca massif rises to the SE above the gentle slopes of block-and-ash flow deposits from the volcano. The steeply dipping lava flow on the left horizon caps hydrothermally altered rocks of a Pleistocene stratovolcano of the Taapaca II complex. The dome complex at the center is of part of the dacitic Pleistocene Taapaca III complex, and the light-colored dome at the right is part of the dacitic Pleistocene-to-Holocene Taapaca IV complex.

The elongated Taapaca massif rises to the SE above the gentle slopes of block-and-ash flow deposits from the volcano. The steeply dipping lava flow on the left horizon caps hydrothermally altered rocks of a Pleistocene stratovolcano of the Taapaca II complex. The dome complex at the center is of part of the dacitic Pleistocene Taapaca III complex, and the light-colored dome at the right is part of the dacitic Pleistocene-to-Holocene Taapaca IV complex.Photo by Lee Siebert, 2004 (Smithsonian Institution).

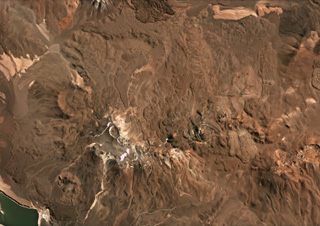

The NW side of Nevados Ojos del Salado volcano rises above Pliocene ignimbrites and pyroclastic deposits of the Barranca Blanca. These deposits are overlain by dacitic pyroclastic-flow deposits from Ojos del Salado. A break in slope about half way up the volcano is the rim of a somma, inside which the modern edifice was constructed. Dacitic lava flows from the summit cone periodically overtopped the somma rim.

The NW side of Nevados Ojos del Salado volcano rises above Pliocene ignimbrites and pyroclastic deposits of the Barranca Blanca. These deposits are overlain by dacitic pyroclastic-flow deposits from Ojos del Salado. A break in slope about half way up the volcano is the rim of a somma, inside which the modern edifice was constructed. Dacitic lava flows from the summit cone periodically overtopped the somma rim.Photo by Oscar González-Ferrán (University of Chile).

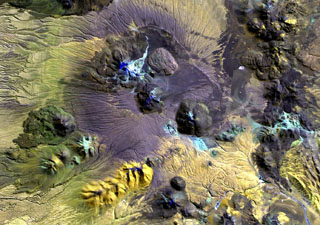

Volcán Mentolat is an ice-filled 6-km-wide caldera in the central part of Magdalena Island, across the Puyuhuapi strait from the town of Puerto Cisnes. A young-looking andesitic lava flow on the west side of the volcano may be its most recent product. Historical reports describe an eruption at the beginning of the 18th century that could refer to this lava flow.

Volcán Mentolat is an ice-filled 6-km-wide caldera in the central part of Magdalena Island, across the Puyuhuapi strait from the town of Puerto Cisnes. A young-looking andesitic lava flow on the west side of the volcano may be its most recent product. Historical reports describe an eruption at the beginning of the 18th century that could refer to this lava flow.Photo by Oscar González-Ferrán (University of Chile).

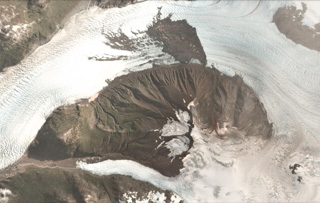

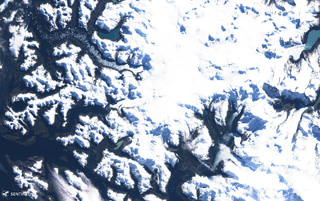

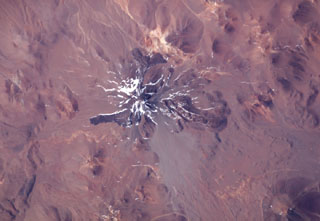

Snow-mantled Volcán Maca, the highest volcano between Lanín and Lautaro, rises to 2960 m NW of Puerto Aisén. This glacier-covered, basaltic-to-andesitic stratovolcano lies within a caldera and contains a summit lava dome. Five flank cinder cones and lava domes lie along a NE-trending fissure that extends 15 km from the summit. The volcano lies along the regional Liquiñe-Ofqui fault zone. Volcan Cay (far right) lies to the NE of Maca.

Snow-mantled Volcán Maca, the highest volcano between Lanín and Lautaro, rises to 2960 m NW of Puerto Aisén. This glacier-covered, basaltic-to-andesitic stratovolcano lies within a caldera and contains a summit lava dome. Five flank cinder cones and lava domes lie along a NE-trending fissure that extends 15 km from the summit. The volcano lies along the regional Liquiñe-Ofqui fault zone. Volcan Cay (far right) lies to the NE of Maca.Photo by Oscar González-Ferrán (University of Chile).

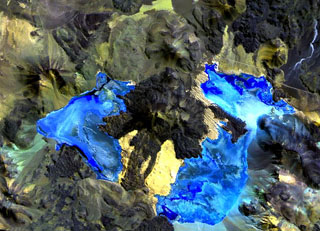

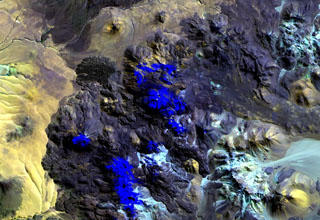

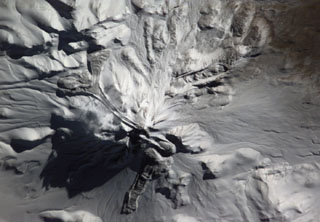

A vertical aerial photograph shows a growing lava dome in the summit of Láscar volcano on March 20, 1992. Three of six summit craters located along an E-W trend are seen in this photo, with north to the top. The lava dome (the dark steaming mass at left center) was first seen on March 4, but may have formed earlier following phreatic explosive eruptions in October 1991. Eruption plumes were visible beginning in late March. Ashfall occurred on May 15 and night glow visible May 21-23 marked the last reported activity of the 1991-92 eruption.

A vertical aerial photograph shows a growing lava dome in the summit of Láscar volcano on March 20, 1992. Three of six summit craters located along an E-W trend are seen in this photo, with north to the top. The lava dome (the dark steaming mass at left center) was first seen on March 4, but may have formed earlier following phreatic explosive eruptions in October 1991. Eruption plumes were visible beginning in late March. Ashfall occurred on May 15 and night glow visible May 21-23 marked the last reported activity of the 1991-92 eruption.Photo by Moyra Gardeweg, 1992 (Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería, Chile).

The 10-km-long, E-W-trending ridge that forms the broad summit of 6176-m-high Aucanquilcha stratovolcano consists of several overlapping volcanic edifices. This view overlooks the southern flank of Aucanquilcha from Puquois. The world's highest mine and permanent human habitation is located at the summit region of Aucanquilcha. No historical eruptions are known from Cerro Aucanquilcha, but postglacial lava flows overlie moraines on the upper southern flanks.

The 10-km-long, E-W-trending ridge that forms the broad summit of 6176-m-high Aucanquilcha stratovolcano consists of several overlapping volcanic edifices. This view overlooks the southern flank of Aucanquilcha from Puquois. The world's highest mine and permanent human habitation is located at the summit region of Aucanquilcha. No historical eruptions are known from Cerro Aucanquilcha, but postglacial lava flows overlie moraines on the upper southern flanks. Photo by Erik Klemetti, 2000 (Oregon State University).

Steam plumes rise from abundant solfataras lining the shores of the acid crater lake where the eruptive activity took place at Tupungatito during the 1960s.

Steam plumes rise from abundant solfataras lining the shores of the acid crater lake where the eruptive activity took place at Tupungatito during the 1960s.Photo by Alejo Contreras (courtesy of Oscar González-Ferrán, University of Chile).

The forested volcanic complex in the lower center of this NASA Space Station image (with north to the left) is Hualique (also known as Apagado). This stratovolcano is located SW of snow-covered Yate volcano (top; left of center) and occupies the peninsula between the Gulf of Ancud and the Reloncaví estuary (upper left). A 6-km-wide caldera is open to the SW. Hornopirén volcano is the small rounded brownish peak below and to the right of Yate volcano.

The forested volcanic complex in the lower center of this NASA Space Station image (with north to the left) is Hualique (also known as Apagado). This stratovolcano is located SW of snow-covered Yate volcano (top; left of center) and occupies the peninsula between the Gulf of Ancud and the Reloncaví estuary (upper left). A 6-km-wide caldera is open to the SW. Hornopirén volcano is the small rounded brownish peak below and to the right of Yate volcano.NASA International Space Station image ISS006-E-42995, 2003 (http://eol.jsc.nasa.gov/).

A somewhat fanciful sketch depicts visitors fleeing a small phreatic explosion from a vent in the summit crater of Antuco volcano on March 1, 1839. Historical eruptions of Antuco have been recorded since the middle of the 18th century. All historical activity has consisted of mild-to-moderate explosive eruptions, with the exception of a flank eruption during 1852-53 that produced a lava flow.

A somewhat fanciful sketch depicts visitors fleeing a small phreatic explosion from a vent in the summit crater of Antuco volcano on March 1, 1839. Historical eruptions of Antuco have been recorded since the middle of the 18th century. All historical activity has consisted of mild-to-moderate explosive eruptions, with the exception of a flank eruption during 1852-53 that produced a lava flow.From the collection of Maurice and Katia Krafft.

An ash-rich eruption column, incandescent at its base, rises above Navidad cinder cone on the NE flank of Lonquimay volcano in January 1989. Still-glowing volcanic bombs litter the flanks of the cone. Tolguaca volcano appears at the left in this view from the SE. Soon after the start of the eruption on December 25, 1988, lava effusion began, producing a lava flow that by the time the eruption ended in January 1990 had traveled 10 km down the NE flank.

An ash-rich eruption column, incandescent at its base, rises above Navidad cinder cone on the NE flank of Lonquimay volcano in January 1989. Still-glowing volcanic bombs litter the flanks of the cone. Tolguaca volcano appears at the left in this view from the SE. Soon after the start of the eruption on December 25, 1988, lava effusion began, producing a lava flow that by the time the eruption ended in January 1990 had traveled 10 km down the NE flank.Copyrighted photo by Katia and Maurice Krafft, 1989.

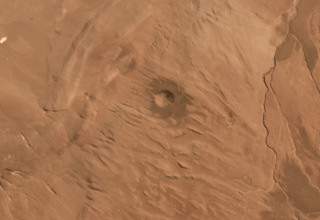

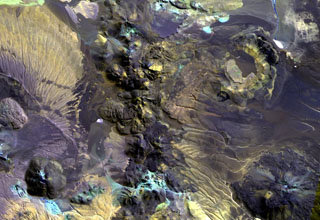

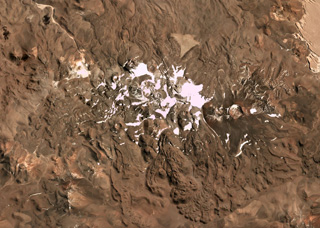

The flanks of Isluga volcano in Chile are formed by numerous lobate lava flows visible in this June 2019 Planet Labs satellite image monthly mosaic (N is at the top; this image is approximately 23 km across). The lavas have lateral levees and pressure ridges especially visible on the southern flanks. The most recent 400-m-diameter summit crater is visible at the western side of the summit area.